Schizophrenia is a major psychotic disorder, with symptoms including changes in perception, feeling, behavior, judgment, ideation, thought process, and motivation. Symptom manifestation is heterogeneous and variable over time (

1). The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is approximately 1 in 100 (

1), and the incidence of schizophrenia in the United States is 11.1 per 100,000 (

2).

Numerous choices of antipsychotic medications with various efficacy and side-effect profiles are available to the clinician. When deciding among treatments, physicians must consider both available evidence and the preferences of patients (

5), which can be quantified by using stated-preference methods, such as discrete-choice experiments (DCEs), also known as conjoint analyses (

6,

7). Previous studies of antipsychotic preference have demonstrated that patients, physicians, and family members collectively place greater importance on productive activity (work or school) compared with positive symptoms or social functioning and place less importance on negative symptoms and side effects (

8,

9). Medication side effects are of greater concern among patients and their families than among clinicians (

10–

14).

Our study built on this research by identifying key attributes (benefits and risks) of antipsychotics and quantifying the trade-offs considered by patients when balancing attributes with formulation and adherence. Novel aspects of our work included use of a structured benefit-risk framework to identify a set of the most critical benefits and harms that physicians consider in antipsychotic treatment decisions, a quantitative approach to assess judgments for trade-offs between formulation and benefits, and a method for quantifying the impact of adherence on these trade-offs.

Discussion

Understanding the importance that patients place on the benefits and risks of antipsychotics and how formulation affects those trade-offs provides insight into past decisions and useful information for future regulatory and treatment decisions. This study built on prior work in this area in three key ways. First, by using a structured benefit-risk approach with input from key opinion leaders and a literature review, we identified a key set of benefits and risks that physicians consider when making decisions about antipsychotic treatment. Second, by incorporating formulation into the choice questions, we obtained quantitative estimates of respondents’ willingness to accept trade-offs between formulation and degree of benefit. Third, by providing information on a hypothetical patient’s adherence, we assessed how perceptions of adherence affected these trade-offs.

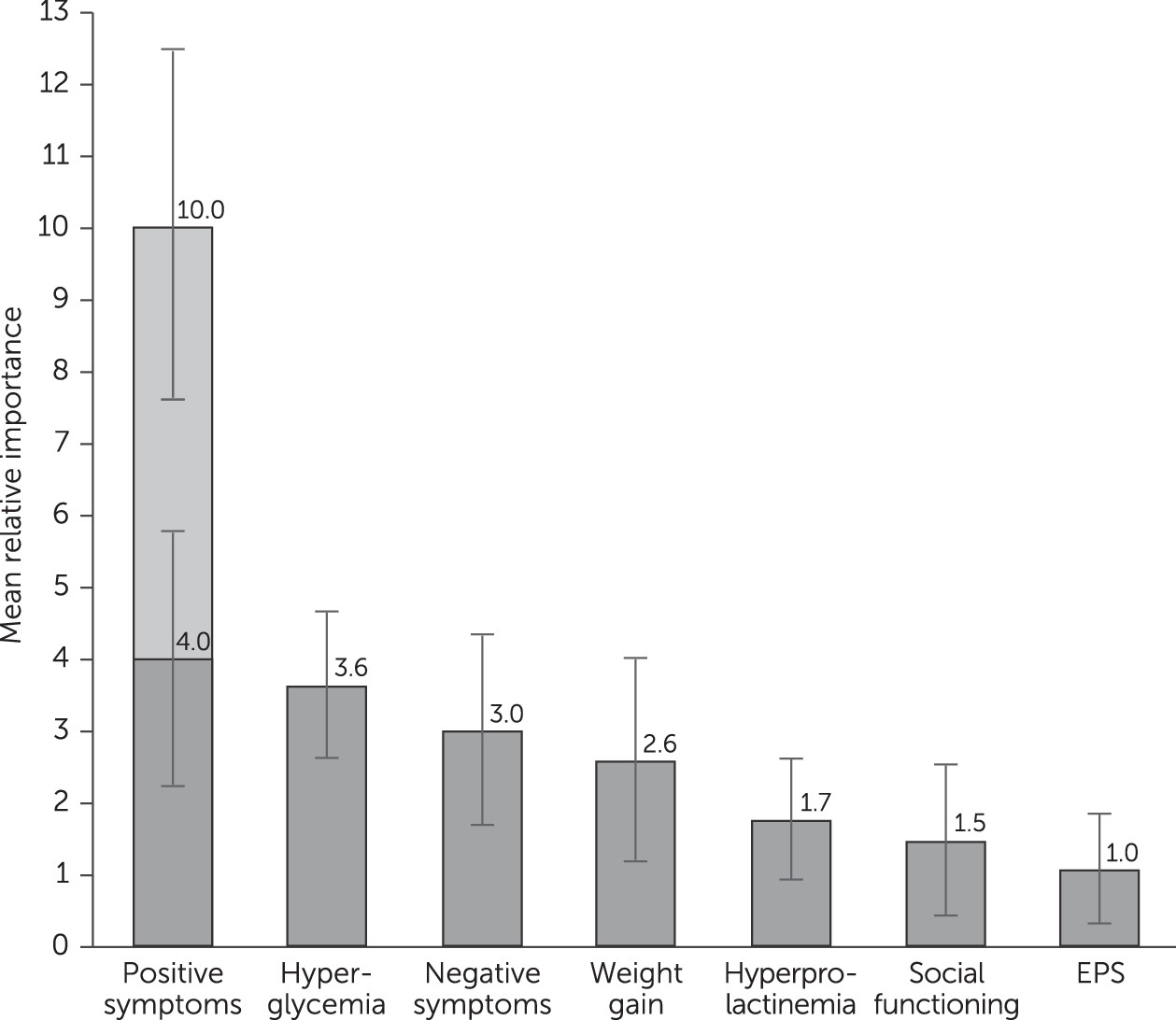

Patients regarded complete removal of positive symptoms as more important than any other symptom or adverse event assessed. Notably, an improvement in positive symptoms from severe to moderate levels was as important as or more important than improvement in any other adverse event included (

Figure 1). This finding suggests that the main driver in antipsychotic treatment decisions is stopping severe positive symptoms. Once a patient with severe positive symptoms shows some improvement, the trade-off between improved efficacy and adverse events becomes more important. Although the rationale behind these measurements was not examined, one possible explanation is that patients understand the dangers associated with severe positive symptoms more than those for negative symptoms, and they may view adverse events as amenable to control by adjustments in dose, choice of antipsychotic, or both.

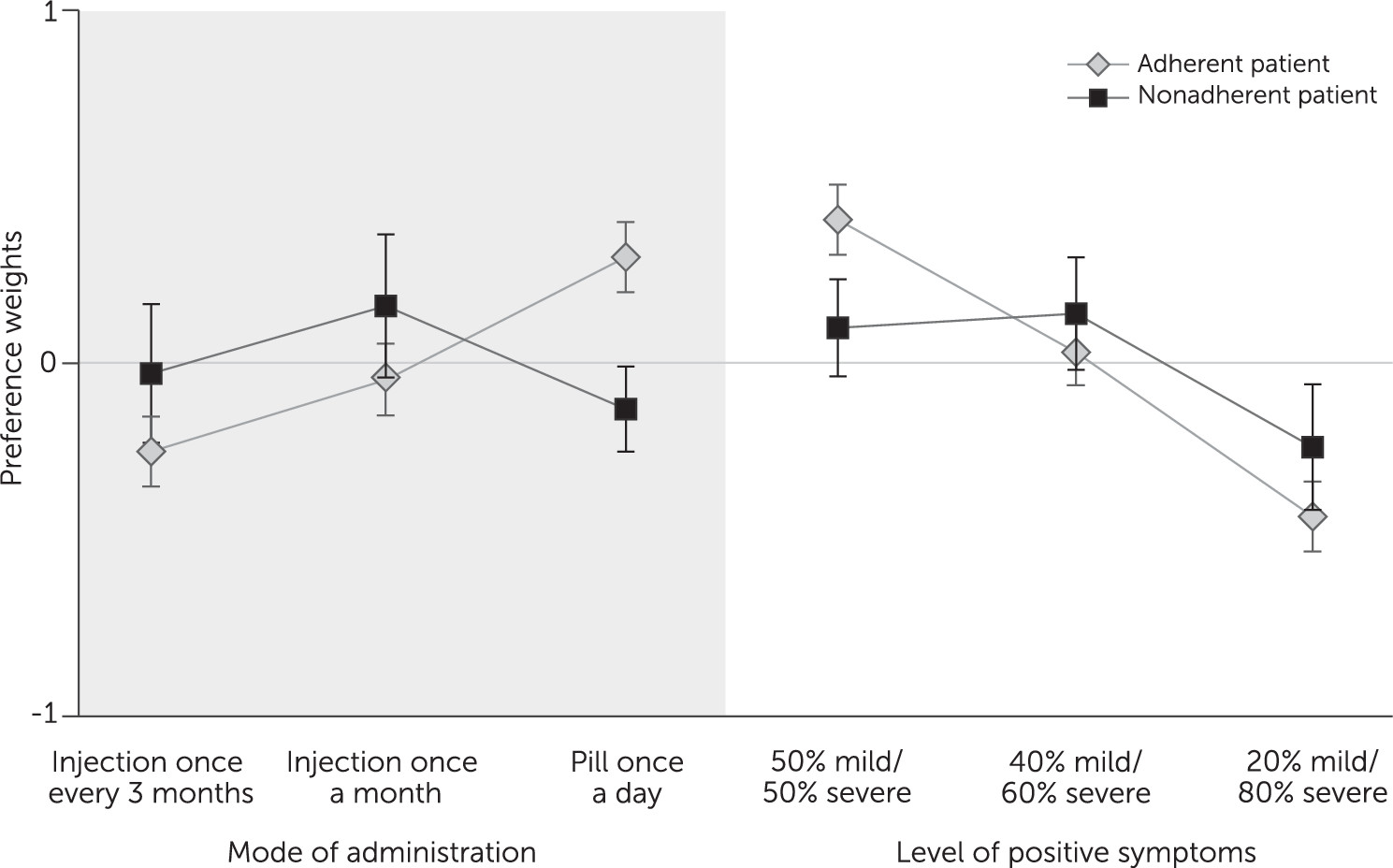

Other findings related to the value respondents placed on switching from an oral antipsychotic to a LAI. As might be expected, this value depended on the hypothetical patient’s adherence behavior. For adherent patients, oral formulations were judged superior to injectables. For nonadherent patients, respondents showed a statistically significant judgment in favor of a one-month LAI over an oral form. The importance of switching to a monthly LAI was similar to the importance of a 26% change in chance of reducing the level of severe positive symptoms. In other words, given the choice between a highly effective oral drug and a somewhat less effective LAI, respondents would choose the LAI for nonadherent patients. If confirmed, such results may be useful for regulatory decision making and clinical practice.

A surprising result is related to patient perceptions about improvements in negative symptoms. An improvement in negative symptoms was considered important only for the elimination of mild symptoms, not for improvements of severe or moderate symptoms to moderate or mild levels. Although patients noted distinctions among the survey descriptions of severe, moderate, and mild negative symptoms (

Table 1) during pretesting, they did not value changes in these levels of severity while taking the survey. This finding may be a consequence of differences between viewpoints of patients and physicians and patients’ limited understanding of the effect of negative symptoms. The absence of approved treatments for negative symptoms (and social functioning) could diminish understanding of these symptoms and the value placed on them, given that there is not much real-world expectation for improvement.

The findings of this study were similar to those of other published studies in which respondents valued improvements in social functioning and positive symptoms more than improvement in negative symptoms and avoidance of side effects (

8,

9). A related study in which the authors assessed psychiatrist judgments about medications’ benefits and risks showed that the psychiatrists and patients had several results in common (

21,

22). Like patients, psychiatrists showed that positive symptoms were their dominant concern. Psychiatrists showed little difference in their opinions about the importance of various formulations for an adherent patient, but as adherence decreased, psychiatrists preferred both one-month and three-month injectables over oral formulations (p<.01). Like patients, psychiatrists would accept up to a 20% to 25% reduction in efficacy in order for a highly nonadherent patient (missed 50% of doses) to switch from a monthly injectable to an oral formulation.

An important consideration is the degree to which the judgments of a panel of patients can be used in the context of individual patient treatment. Mean results from a panel may not be informative about individual preferences. However, panel results can be considered in a manner similar to the consideration of clinical data in treatment guidelines. Both provide evidence about patient populations and enable physicians to better compare the small samples they treat with the larger populations described in the guidelines. Treatment decisions potentially can then be based on both clinical study data and preference data. Mean preference results may be particularly valuable when treating a patient who chooses not to indicate personal preferences or is incapable of doing so.

There were several noteworthy limitations of this study. First, we designed the survey to help respondents interpret the attributes consistently and as intended. However, evaluating choice tasks could be cognitively difficult for patients with schizophrenia, although recent work suggests that is not the case (

10). A training section of the survey provided attribute definitions and practice questions. Second, as in all DCE studies, experimental control over the decision stimuli required respondents to evaluate hypothetical choice alternatives. Thus there was potential for hypothetical bias. The study minimized hypothetical bias by using patient-friendly descriptions of treatment attributes that reflected clinically realistic outcomes.

A third limitation was that constraints on cognition limited the number of endpoints that could be considered simultaneously by survey respondents. We used a structured approach for endpoint selection to mitigate this limitation.

Fourth, unlike positive and negative symptoms, social functioning did not include a level for no symptoms or complete cure. This level was excluded because, when pretesting the physician survey on which this patient survey was based, physicians were unable to accept a scenario in which negative symptoms were unaccompanied by limitations on social functioning. We posited that patients would have a similar concern. If the full range of social functioning was included, social functioning might have shown greater importance compared with negative symptoms. Additionally, using alternative definitions of social functioning that reference jobs, independent housing, or time with friends or family may have led participants to attach greater importance to this attribute.

Fifth, this study surveyed a convenience sample of patients from the United States with access to the Internet. This design limits the confidence with which these results can be generalized. As suggested by

Table 3, this sample represents a more educated population than is typical for patients with schizophrenia. Future research using a randomized patient sample to verify our findings would be valuable. Readers should also understand that these relationships may change over time as understanding of schizophrenia and its treatment evolves.

Sixth, this study was not designed, nor powered, to address the question of whether judgments would change depending on experience with a particular adverse event, such as EPS, or with adherence challenges. Any potential differences were averaged out. However, a post hoc test on results for the 198 patients who answered a question about self-assessed adherence showed no difference between the groups who did or did not adhere to medication. With a larger sample size, a study could show meaningful differences in judgment on the basis of personal or family medical history and could potentially provide better guidance for individual patient treatment.

Seventh, the survey assessed judgment, which is distinct from personal preference or choice. Schizophrenia patients are very sensitive about revealing personal information, and prior DCE work showed that such patients answer hypothetical questions about others (judgments) more easily than about themselves (preferences) (

10). Formulating the questions as judgments also avoided confusion with patients’ experiences and expectations about how treatments could affect their own emotional responses, encouraged objectivity, and reduced potential yea-saying bias compared with a question about what patients would choose for themselves (

10,

31–

34). Use of the results as indicators for personal treatment decisions assumes that the respondents’ judgments are a valid representation of personal preference.

Finally, although DCE surveys could be conducted through in-person interviews, many researchers believe that computerized administration assures respondents of anonymity and reduces yea-saying and interviewer bias. Results from online DCE studies are generally not statistically significantly different from those elicited through face-to-face interviews (

35,

36), and several DCE studies using online patient panels have been published (

6,

7,

16,

37).