According to the 2012 Canadian Mental Health Survey, 10% of the Canadian population age 15 and over had experienced at least one mental disorder in the previous 12 months (

1). It is acknowledged that only a minority of people with mental disorders (33%−46%) seek help from a health care professional (

2,

3) and that perceived need is a significant predictor of mental health service use (

4,

5). In epidemiologic studies, participants may perceive needs primarily for information (about mental disorders, treatments, or services), medication, and counseling (including psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy). A need is considered to be fully met when a person receives help meeting all his or her expectations. In other cases, the help may only partly fulfill the need, or no support is provided at all and the need is unmet (

1).

According to previous studies, people diagnosed as having a mental disorder, especially depression (

6–

8), panic disorder (

9) and other anxiety disorders (

8), or a co-occurring mental disorder and addiction (

6), perceive more unmet needs than people without these diagnoses. A high level of psychological distress (

1,

6,

10) and absence of chronic general medical illnesses (

1) are other clinical variables correlated with perceived unmet needs. These variables are also strongly associated with mental health service use (

11–

13). The findings related to sociodemographic variables are inconsistent: studies have shown that the people most likely to have perceived unmet needs are younger (

14–

16) or older (

7) and have lower (

4) or higher (

10) levels of education. In regard to socioeconomic variables, unmet needs are associated with being unemployed (

17), having no insurance coverage (

14,

18), and having little social support (

15,

17). A negative association has also been found between quality of life and perceived unmet needs (

19–

24) among individuals with severe mental disorders.

To our knowledge, no study based on a conceptual framework that includes several categories of variables has analyzed perceived unmet needs in a catchment area. In studies of health service use, Andersen’s behavioral model is widely used (

5). This model explains health service use in terms of predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Predisposing factors include individual characteristics, such as age, gender, civil status, and self-perceived health. Enabling factors, such as income, social support and neighborhood, also influence health service use. Finally, need factors refer to clinical variables, such as number and type of disorders (

5). Many variables reported as being associated with health service use according to Andersen’s behavioral model, such as self-perceived mental (

25) or general medical health (

26) and spirituality (

27), have rarely been analyzed in studies of perceived unmet needs. To our knowledge, other variables, such as stress, aggressive behavior, and perception of the quality or safety of the neighborhood, have received no attention from researchers. People experiencing several stressful events or perceiving their neighborhoods as disadvantaged, unsafe, or hostile may be more likely to perceive unmet needs. Furthermore, people with aggressive behavior may have more trouble accessing services and may therefore be more likely to view their needs as unmet.

Several studies have described the proportion of unmet needs for information, medication, and counseling (

28–

32). However, as far as can be ascertained, only one has analyzed variables associated with unmet needs in each of those domains (

1). Sunderland and Findlay (

1) found that people with mental disorders, with greater psychological distress, and without chronic general medical conditions are more likely to have perceived unmet needs overall and mainly for counseling. However, only a limited number of clinical variables were considered. Greater knowledge about variables associated with perceived unmet needs would help identify people who fail to obtain the required care. Considering that mental disorders have biopsychosocial causes and that treatment should not be limited to medication but should also cover psychosocial aspects (

33), perceived unmet needs for information, counseling, and medication may be mainly associated with distinct variables.

This study had two objectives: to compare variables associated with perceived partially met and unmet information, medication, and counseling needs among 571 people residing in a Canadian epidemiologic catchment area and to identify variables associated with overall perceived unmet needs. On the basis of Andersen’s behavioral model and on the literature on needs and on health service use, it was hypothesized that perceived unmet need for information is negatively associated with social support, neighborhood perception (enabling factors), and health service use variables; that unmet need for counseling is more highly associated with socioeconomic variables (enabling factors), compared with unmet need for medication, which in turn is more likely to be associated with diagnoses (need factors); and that overall perceived unmet needs are mainly associated with need factors and negatively associated with health service use variables.

Methods

Design, Setting, and Survey Sample

This research stemmed from the third wave (T3) (January 2012 to July 2013) of a longitudinal study carried out in an epidemiologic catchment area in Montreal, the second largest city in Canada. The catchment area, with a population of 269,720, includes four neighborhoods, with populations ranging from 29,680 to 72,420 inhabitants. Further details about the catchment area have been published elsewhere (

24,

34).

The sample was equally distributed among the four neighborhoods. The data were weighted by gender and age at T1 (June 2007 to December 2008) to obtain precise information about mental disorders in the population. Participants provided written informed consent to take part in the study. The ethics board from a psychiatric hospital approved the research. The retention rate at T3 was 72%, which is quite similar to that of other epidemiological studies (69% to 76% after two to five years [

35,

36]). [Further details about the catchment area and about the sample are available in an

online supplement to this article.]

Variables and Instruments

The dependent variable—perceived unmet needs—was measured using the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ) (

37). The PNCQ assesses perceived needs (for information, counseling, medication, social intervention, and skills training) in the previous 12 months. It has good reliability (κ=.60 for interrater reliability) (

37). On the basis of Andersen’s behavioral model (

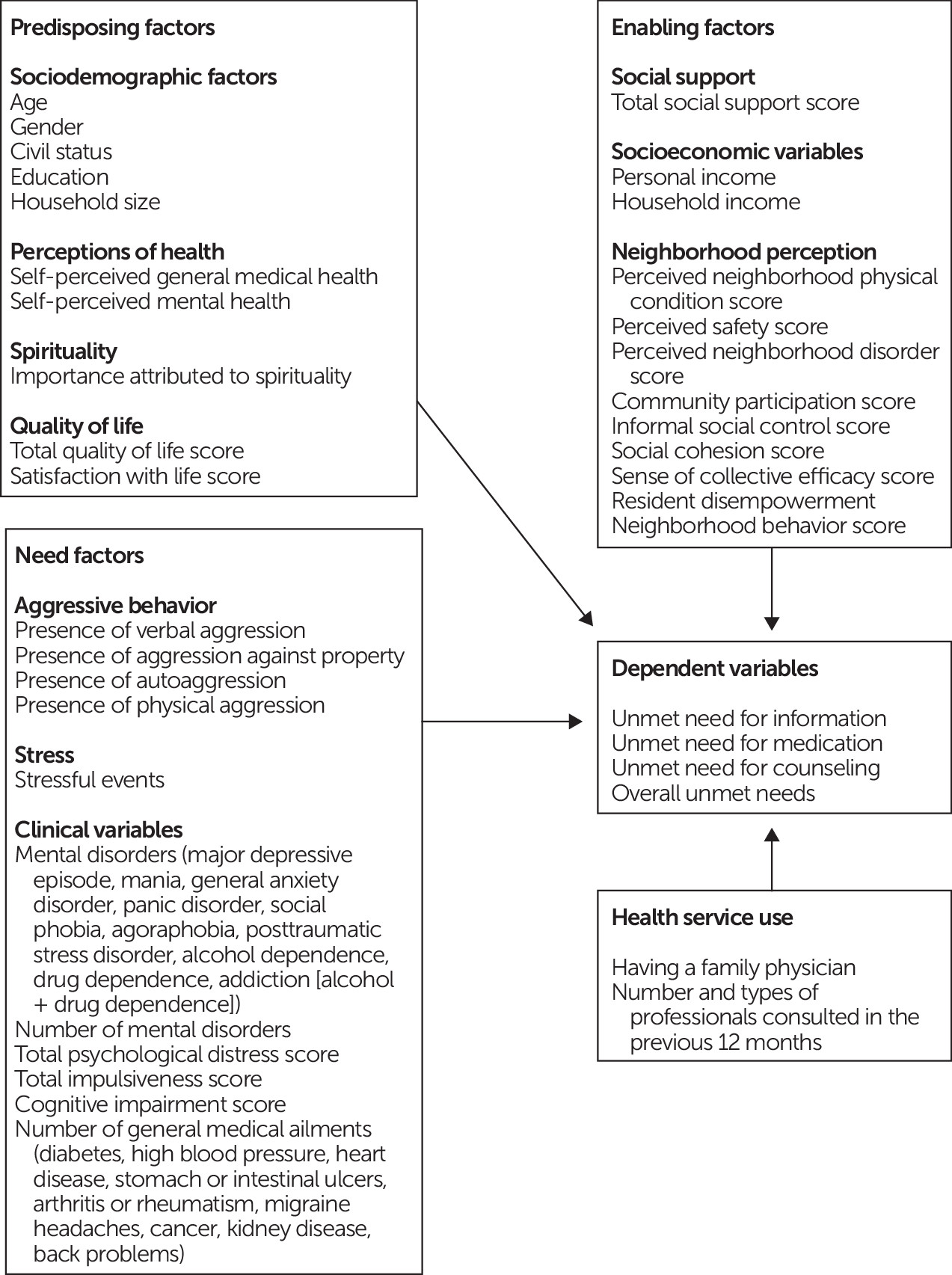

30), the independent variables were grouped under predisposing, enabling, and need factors and service use variables (

Figure 1). [The 18 measurement instruments used are described in detail in the

online supplement.]

Analyses

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were conducted. Univariate analyses produced a frequency distribution for categorical variables and mean values, along with a standard deviation for continuous variables. Four models were developed in relation to the four dependent variables: perceived unmet need for information need, perceived unmet need for medication, perceived unmet need for counseling, and overall perceived unmet needs (including needs for social intervention and skills training). The first three models used multinomial logistic regression, and the fourth used multiple logistic regression. The models were developed around the variables shown in

Figure 1, following bivariate analyses. Variables with a significant association with each dependent variable, for an alpha value set to p=.10, were entered into the model by using a backward-elimination approach. For all models, alpha values were set at p=.05. Goodness of fit and total explained variance were calculated for each model.

Results

Of the 2,334 persons interviewed, 571 (24%) expressed a need for information, medication, or counseling in relation to mental health, and these participants were selected for further analysis. Of them, 467 (82%) said that their needs were fully or partially met, while 104 (18%) reported that all their needs were unmet.

Table 1 presents data on the participant characteristics.

The largest proportion of the 571 participants perceived a need for counseling (70%, N=397), followed by information (49%, N=279) and medication (49%, N=279). The proportion of participants perceiving a fully met need, a partially met need, and an unmet need, respectively, was 60% (N=239), 10% (N=38), and 30% (N=120) for counseling; 76% (N=213), 6% (N=16), and 18% (N=50) for information; and 92% (N=257), 4% (N=12), and 4% (N=10) for medication. Finally, of the 180 perceived unmet needs reported by the 571 persons, 67% (N=120) were for counseling, 28% (N=50) for information, and only 6% (N=10) for medication.

Table 2 presents the independent variables associated with perceived partially met and unmet needs for information, medication, and counseling. Compared with participants with a fully met need for information, those with a partially met need were more likely to be female (88% versus 64%), to perceive their mental health as poor (predisposing factors), to be more positive about the physical conditions of their neighborhood and their sense of collective efficacy, and to be less positive about the neighborly behaviors (for example, lending a neighbor a tool or taking care of an out-of-town neighbor’s house) and their capacity for informal social control (enabling factors). Compared with participants with a fully met need for information, those with a perceived unmet need were more likely to commit aggression against property (need factor), to be less positive about neighborly behavior and their capacity for informal social control (enabling factors), and to have seen fewer health care professionals (health service use variable). This model explained 33% of the total variance associated with perceived unmet need for information.

Compared with participants with a fully met need for medication, those with a partially met need were more likely to perceive their general medical health as poor (predisposing factor) and to commit aggression against property (need factor). People with a totally unmet need for medication were more likely than those whose need was fully met to give no importance to spirituality (predisposing factor), to perceive their neighborhoods as unsafe (enabling factor), and to have experienced a greater number of stressful events (need factor). This model explained 25% of the total variance associated with perceived unmet need for medication.

Compared with participants with a fully met need for counseling, those with a partially met need had poorer self-perceived mental health (predisposing factor), whereas those with a totally unmet need for counseling were more likely to exercise a lower level of informal social control (enabling factor), to show verbal aggression (need factor), and to see fewer health care professionals (health service use variable). This model explained 27% of the total variance associated with perceived unmet need for counseling.

Variables associated with overall perceived unmet needs were female gender and younger age (predisposing factors); a higher score on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment scale (indicating cognitive dysfunction), addiction, and verbal aggression (need factors); and having seen fewer health care professionals (health service use variable) (

Table 3). This model had an acceptable goodness of fit and explained 30% of the total variance associated with overall perceived unmet needs.

Discussion

The proportion of participants expressing needs in our study (24%) was somewhat higher than the proportions (14% to 23%) estimated in previous epidemiological studies that used the PNCQ (

4,

28,

29,

31). These differences may be explained by the demographic structure of the setting (poverty and high prevalence of psychological distress) or by the presence of a psychiatric hospital in the catchment area. However, the proportions of the sample reporting fully met needs for medication (92%), information (76%), and counseling (60%) were quite similar to estimates in the 2012 Canadian Mental Health Survey (91%, 70%, and 65%, respectively) (

1).

As in previous studies, perceived unmet and partially met needs were more common for counseling, followed by information (

1,

28–

30,

32). The high proportion of the perceived unmet need for counseling suggests that people with common mental disorders (depression and anxiety disorders) would prefer to receive both medication and psychotherapy or to have better access to psychologists (

38). An unmet need for counseling cannot be explained by a lack of psychologists, because the ratio of 104 psychologists to 100,000 individuals in Quebec is more than double the Canadian average (48 per 100,000) (

39). Because Canadian public health insurance plans only partly cover counseling services, low-income, uninsured people have limited access to psychologists (

40). In a report on the performance of mental health services, the Quebec Commissioner for Health and Welfare recommended access to psychotherapy for all, as has been mandated in other countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom (

41). In regard to unmet need for information, many health professionals—unlike people with mental disorders—see this as a secondary issue (

42). According to a recent study, limited consultation time and the difficulties that some people experience in asking questions are other factors that explain a perceived unmet need for information (

43). Low education levels (

4), cultural and linguistic barriers (

44), or cognitive problems may also explain difficulties in obtaining and understanding information. Finally, consistent with previous findings (

1,

28,

29,

31,

32), the proportions of perceived unmet and partially met need for medication in our study were very low. However, it has been shown that people with a fully met need do not necessarily feel satisfied with taking medications (

43) or may not be taking them properly (

45).

Results did not strongly support the study hypotheses. Perceived partially met and unmet need for information was not associated with social support (enabling factor). No association was found between socioeconomic variables (enabling factors) and a perceived partially met or unmet need for counseling. An unmet need for medication was not associated with diagnosis (need factor). However, the variables associated with needs for information and counseling were distinct from the variables associated with a need for medication.

In regard to health service use, the number of health care professionals consulted was negatively associated with perceived unmet information and counseling needs. It seems logical that people who visit fewer health care professionals are more likely to have perceived unmet needs in these two domains. Treating mental disorders usually requires several approaches and complementary treatments, and seeing more professionals might increase treatment motivation and outcomes (

20,

46,

47).

In regard to enabling factors, perception of the neighborhood (neighborhood physical condition, sense of collective efficacy, neighborly behavior, and informal social control) were more strongly associated, positively or negatively, with a partially met and unmet need for information. Neighbors who offer social support may influence people with mental disorders by directing them to professionals, providing information on available services, and offering assistance to reduce barriers to health care use (

33,

48).

In regard to need factors, the association between stressful events and a perceived unmet need for medication suggests that some people had trouble finding a psychiatrist or a family physician willing to prescribe medication for their stress. The finding that people who committed aggression against property were more likely to perceive their medication and information needs as unmet or only partially met, compared with those who did not commit such aggression, suggests that some individuals may have had problems with the law and therefore may have had limited access to health services because of the reluctance of some professionals to serve this population (

49). The issue of stigma might explain the association between verbal aggression and a perceived unmet need for counseling. Fighting stigma is one of the main recommendations of the Quebec Commissioner of Health and Welfare aimed at increasing the performance of mental health services (

41).

In regard to predisposing factors, it stands to reason that poor self-perceived mental health was found to be correlated with a partially met need for information. Although medication usually offers rapid improvement of mental disorders, counseling is reported to provide more sustained recovery (

50), suggesting that people with more severe or complex symptoms might expect complementary treatments, such as psychotherapy and medication. Previous studies have found a greater level of satisfaction among individuals with mental disorders receiving both medication and psychosocial treatment (

33,

48). It is more difficult to explain why people who grant little importance to spirituality are more likely than those who do not to have a perceived unmet need for medication. One possibility is that religion or spirituality is a significant protective factor against mental disorders (

51).

Finally, consistent with the final hypothesis, overall perceived unmet needs were quite strongly associated with need factors and health service use variables. The fact that people with substance use disorders were more likely to have overall perceived unmet needs may be a consequence of stigma (

52) or may stem from a lack of treatment resources. Many professionals are reluctant to treat these clients (

53). People with substance use disorders are also more likely to move frequently and to abandon treatment, and they are less likely to use health services (

54–

56). Furthermore, in Quebec, as elsewhere in the world, few specialized services exist for addiction or for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders (

57). The association between overall unmet needs and higher cognitive functioning is difficult to explain. It suggests that people with severe cognitive disorders are more likely to be in treatment. The negative association between the number of professionals consulted and overall perceived unmet needs is reasonable, considering that perceived unmet needs were predominantly related to counseling. Furthermore, previous studies have found that perceived unmet needs were more frequent among younger people (

14–

16). Finally, the fact that males tend to consult health care professionals only after a sharp deterioration in their mental or general medical conditions may explain why they were less likely to have perceived unmet needs (

58).

This study had a number of limitations. First, the results may reflect characteristics of the population in the catchment area and may not be generalizable to other areas or populations. Second, the severity of mental disorders was not considered. Previous studies have reported a link between perceived unmet needs and level of disability (

59). Third, sample attrition from T1 to T3 may have introduced a bias, because participants who remained in the cohort were different from those lost to follow-up. Finally, because all the variables (dependent and independent) emanated from a one-time measurement, it is not possible to infer causality between variables.

Conclusions

This study was the first to compare variables associated with perceived unmet needs for information, medication, and counseling as well as overall perceived unmet needs, based on a comprehensive conceptual framework. The findings indicate that counseling and information needs go unmet more often than the need for medication. The high prevalence of unmet needs, particularly for counseling, seems to be associated with public policies, because unlike medication, counseling is only partially covered by the Quebec public insurance plan. Equitable access to psychotherapy could reduce unmet need for counseling. Moreover, the results show the importance for mental health services of taking neighborhoods into account in disadvantaged areas. Increasing the provision of mental health care in primary care settings could facilitate better access to information for people living in disadvantaged situations. Also, the findings suggest that young people and people with addiction were more likely to have needs that went entirely unmet. Greater effort should be devoted to improving specialized services for these groups and to development of integrated treatment for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Finally, fighting stigma should be another priority for mental health services.