Research, Data, and Evidence-Based Treatment Use in State Behavioral Health Systems, 2001–2012

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Methods

Data Source and Elements

Sample

EBTs tracked.

Years examined.

Outliers and Missing Data

Data analysis

Results

State Use of Evidence and Activities to Promote EBTs

| Question and activity | 2001 | 2002 | 2004 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Does the state mental health authority (SMHA) do or has it done the following? | ||||||||||||||

| Conducted research on or evaluations of client outcomesb | 13 | 29 | 32 | 84 | 36 | 75 | 42 | 88 | 40 | 83 | — | — | — | — |

| Implemented a statewide client outcomes-monitoring system | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 29 | 58 | 29 | 64 |

| Integrated its client data sets with client data sets from other agencies | — | — | 23 | 49 | 28 | 58 | — | — | 26 | 54 | 25 | 50 | 24 | 53 |

| Produced a directory of research or evaluation projects | 11 | 23 | 11 | 23 | 7 | 15 | 9 | 19 | 9 | 19 | 11 | 23 | — | — |

| Operated a research center or institute | 8 | 17 | 8 | 17 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 15 | 7 | 15 | 4 | 8 | — | — |

| Funded a research center or institutec | 6 | 13 | 11 | 23 | 9 | 19 | 13 | 27 | 8 | 17 | 15 | 31 | — | — |

| What initiatives are you implementing to promote the adoption of EBTs? | ||||||||||||||

| Awareness and trainingc | — | — | 38 | 75 | 34 | 71 | 41 | 84 | 43 | 86 | 44 | 88 | 37 | 86 |

| Consensus building among stakeholdersd | — | — | 38 | 79 | 36 | 75 | 44 | 90 | 42 | 84 | 41 | 82 | 31 | 72 |

| Incorporation in contractsc | — | — | 20 | 42 | 21 | 44 | 30 | 61 | 29 | 58 | 37 | 74 | 29 | 67 |

| Monitoring of fidelityd | — | — | 25 | 52 | 27 | 56 | 34 | 69 | 36 | 72 | 35 | 70 | 29 | 67 |

| Financial incentivesc | — | — | 8 | 17 | 15 | 31 | 14 | 29 | 18 | 37 | 19 | 38 | 15 | 35 |

| Modification of information technology systems and data reports | — | — | 20 | 42 | 22 | 46 | 27 | 55 | 25 | 50 | 29 | 58 | 22 | 51 |

| Specific budget requestsd | — | — | 14 | 29 | 19 | 40 | 25 | 51 | 19 | 39 | 19 | 38 | 12 | 28 |

| Does the SMHA conduct research on or evaluations of the following? | ||||||||||||||

| Utilization rates | — | — | 33 | 87 | 36 | 78 | 40 | 83 | 39 | 81 | — | — | — | — |

| Change in functioningc | — | — | 26 | 68 | 29 | 63 | 35 | 73 | 37 | 77 | — | — | — | — |

| Penetration rates | — | — | 28 | 74 | 30 | 65 | 35 | 73 | 36 | 75 | — | — | — | — |

| Question and activity or EBT | Time trend | Intercept | Linear slope | Quadratic slope | Cubic slope | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | ||

| Activities to support research, data use, and EBTs | |||||||||

| Does the state mental health authority (SMHA) do or has it done the following? | |||||||||

| Conducted research on or evaluations of client outcomes | Fixed | –.681 | .014 | 1.577 | <.001 | –.327 | .008 | .021 | .030 |

| Implemented a statewide client outcomes-monitoring system | Random | –.721 | .656 | .113 | .484 | ||||

| Integrated its client data sets with client data sets from other agencies | Random | .242 | .372 | –.012 | .744 | ||||

| Produced a directory of research or evaluation projects | Random | –1.303 | <.001 | .004 | .878 | ||||

| Operated a research center or institute | Random | –1.412 | <.001 | –.028 | .188 | ||||

| Funded a research center or institute | Random | –1.464 | <.001 | .054 | .031 | ||||

| What initiatives are you implementing to promote the adoption of EBTs? | |||||||||

| Awareness and training | Random | 1.049 | <.001 | .073 | .029 | ||||

| Consensus building among stakeholders | Random | .765 | .009 | .255 | .019 | –.023 | .022 | ||

| Incorporation in contracts | Random | –.419 | .141 | .119 | .008 | ||||

| Monitoring of fidelity | Random | –.277 | .420 | .264 | .019 | –.016 | .066 | ||

| Financial incentives | Random | –1.287 | <.001 | .081 | .032 | ||||

| Modification of information technology systems and data reports | Random | –.269 | .318 | .470 | .220 | ||||

| Specific budget requests | Random | –1.131 | .002 | .311 | .019 | –.027 | .013 | ||

| Does the SMHA conduct research on or evaluations of the following? | |||||||||

| Utilization rates | Random | 1.012 | .014 | .041 | .502 | ||||

| Change in functioning | Random | .089 | .779 | .134 | .005 | ||||

| Penetration rates | Random | .449 | .136 | .070 | .115 | ||||

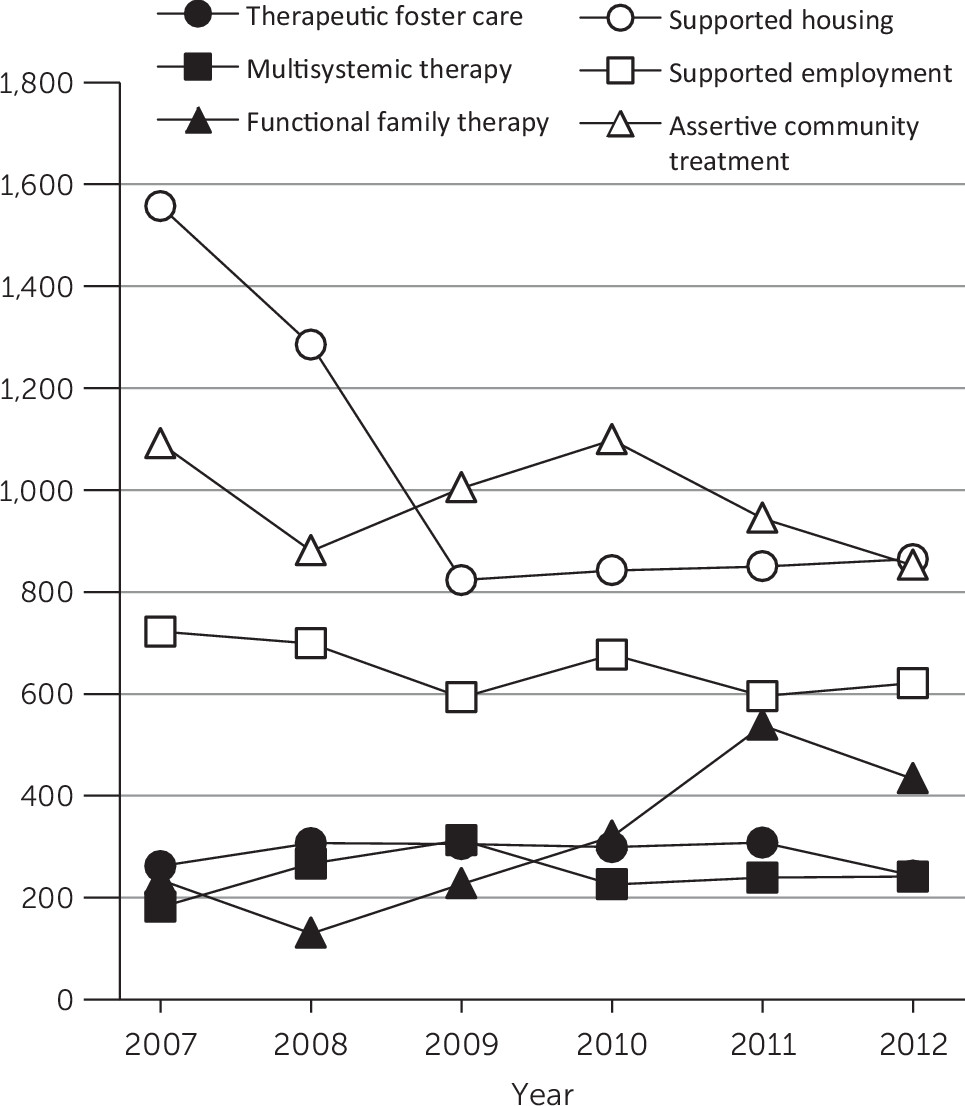

| Numbers of people receiving specific EBTs | |||||||||

| Therapeutic foster care | Random | 6.309 | <.001 | .107 | .019 | –.021 | .016 | ||

| Multisystemic therapy | Random | 5.611 | <.001 | .089 | .020 | ||||

| Functional family therapy | Random | 6.508 | <.001 | –.004 | .938 | ||||

| Supported housing | Random | 7.727 | <.001 | –.259 | .029 | .104 | .019 | –.011 | .021 |

| Supported employment | Random | 6.948 | <.001 | .037 | .394 | ||||

| Assertive community treatment | Random | 7.212 | <.001 | .033 | .163 | ||||

| Rates of adults with serious mental illness and children with serious emotional disturbance receiving EBTs | |||||||||

| Therapeutic foster care | Fixed | –3.284 | <.001 | .303 | .015 | –.132 | .014 | .014 | .055 |

| Multisystemic therapy | Fixed | –4.013 | <.001 | .552 | .010 | –.293 | .045 | .039 | .057 |

| Functional family therapy | Fixed | –3.874 | <.001 | .737 | .042 | –.311 | .051 | .035 | .066 |

| Supported housing | Fixed | –.53 | <.001 | .004 | .849 | .045 | .004 | –.009 | .002 |

| Supported employment | Random | –3.309 | <.001 | .005 | .906 | ||||

| Assertive community treatment | Random | –3.41 | <.001 | –.013 | .459 | ||||

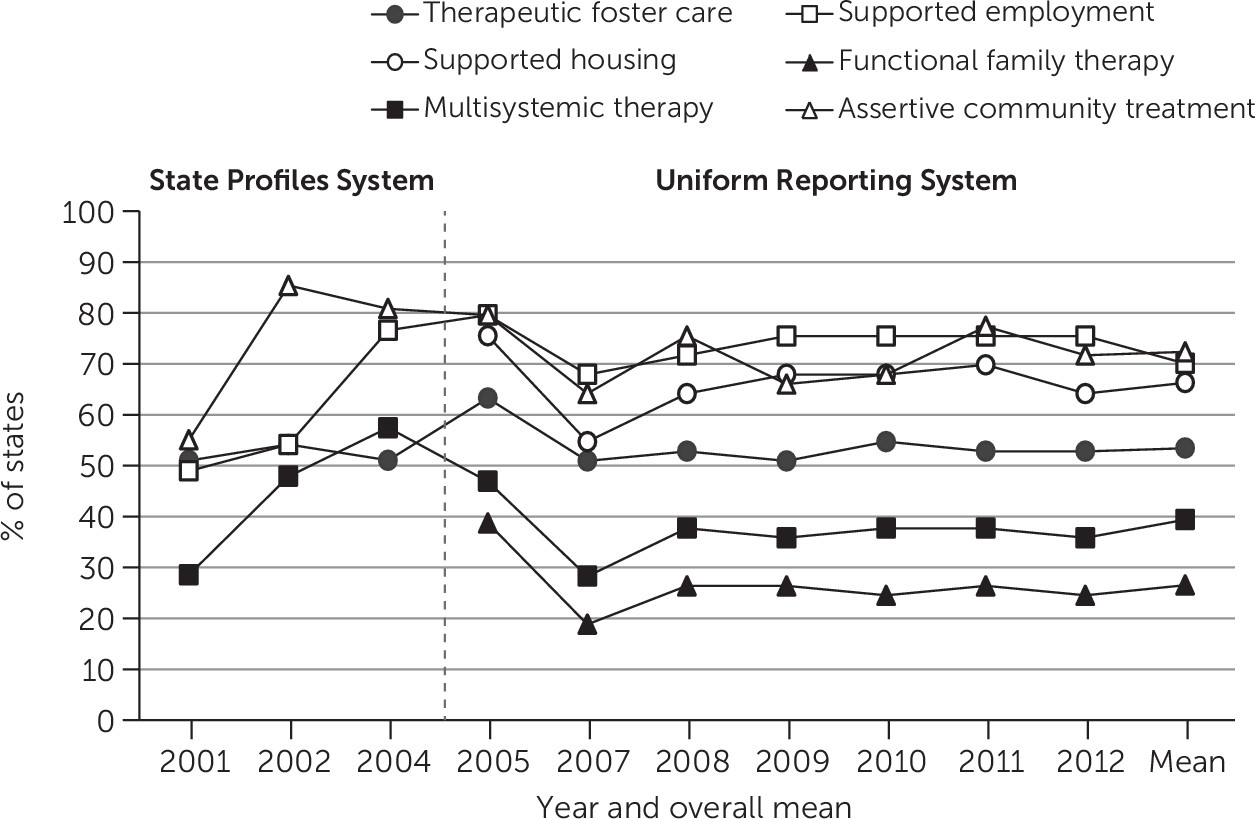

States With EBT Services Available

| EBTb | Slope 2001–2005 | Slope 2007–2012 | Slope 2005–2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time trend | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | Coefficient | p | |

| Therapeutic foster care | Random | .347 | <.001 | .051 | .285 | ||

| Multisystemic therapy | Fixed | .390 | .004 | .021 | .653 | ||

| Supported employment | Random | .458 | <.001 | .043 | .349 | ||

| Assertive community treatment | Random | .133 | .020 | –.081 | .119 | ||

| Functional family therapy | Random | –.056 | .202 | ||||

| Supported housing | Random | –.010 | .826 | ||||

Number of Clients Served by Specific EBTs

Rates of Clients Served

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 27.12 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Cover: Assinibone hand drum, by Werner Forman. From the Plains Indian Museum, BBHC, Cody, Wyoming. Photo credit: HIP/Art Resource, New York City.

History

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).