In recent years, perceptions of ideal doctor-client interactions have shifted from the paternalistic model to a more consumer-oriented approach. In particular, the model of shared decision making (SDM) has attracted attention (

1). SDM aims to change the traditional power asymmetry between doctors and patients by strengthening the exchange of information and the decisional position of patients. There are many good reasons for supporting SDM, including ethical (clients’ basic right to participate in decision making), sociological (changes in clients’ expectations), and utilitarian (increasing clients’ satisfaction and improving adherence) arguments (

2).

To implement SDM, physicians and clients must change their accustomed communicative behaviors. Physicians must follow certain steps to reach shared decisions (for example, sharing information and offering choices) (

3). In addition, clients should exhibit certain competencies for SDM (

4). Many authors have suggested that consumers should play a more active role in consultation and in decision making (

5). Several client skills or behaviors have been proposed as being helpful for SDM (

5,

6)—for example, showing an interest in therapy, paying attention to what the doctor says, and actively seeking information from the doctor about the disorder and treatment options (

7). Although these competencies are doubtless helpful for arriving at shared decisions, they do not really differentiate between client behavior in the paternalistic model and in SDM. For example, client behavior that is clearly atypical in the paternalistic model but typical in SDM involves expressing one’s views, daring to challenge the doctor’s opinion, and openly speaking out about disagreements with the doctor, which has been labeled “critical and participative communication” (

7).

Many people with mental illness do not express their views in medical consultations (

6). Therefore, several studies have sought to identify predictors of patients’ preferences in regard to decision making. Younger age, higher education, dissatisfaction with treatment, and attribution of control are a few of the patient characteristics that have been found to be associated with greater preferences for participating in decision making (

8). With respect to patient behavior, results of a qualitative study suggest that factors such as depressive symptoms, thought disorder, lack of motivation or interest, and a feeling of powerlessness are barriers to active patient behavior that might facilitate SDM (

6).

Although not yet addressed in research, another important barrier to more active patient behavior may be self-stigma, which is common among people with affective and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

9,

10). Some people with mental illness accept the common prejudices of society and lose self-esteem, resulting in shame and self-stigma (

11). Self-stigma can lead to a “why try” effect (for example, “I am not able to work” or “I am not worthy to receive good mental health care”), resulting in adverse outcomes, such as demoralization or poor goal attainment (

12). In addition, self-stigma has been linked to reduced seeking of mental health information (

13), less service use (

14), and poor quality of the therapeutic alliance (

15), indicating that self-stigma may affect interactions in clinical settings.

Thus, consumers with high self-stigma might have less desire to participate in decision making and may exhibit more passive behavior in clinical settings (“Why should I try to engage in medical decision making?”). These individuals may be less likely to engage in and benefit from SDM because SDM requires active input from consumers. Individuals with high self-stigma could thus be more frequently involved in paternalistic decision making (

5), which is less likely to support self-management and empowerment. In the long run, this may be another way in which self-stigma leads to poorer health outcomes.

This study aimed to explore whether self-stigma and shame are associated with consumers’ participation preferences and behavior in consultations. We expected that higher levels of self-stigma and shame would lead to more passive behavior in mental health consultations.

Methods

We used data from a large cross-sectional study that aimed to develop a new measure for client behavior in the psychiatric consultation. From March to December 2014, we recruited participants with either a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (N=126) or an affective disorder (N=203) diagnosis. Inpatient units of various psychiatric hospitals in Germany and outpatient departments and psychiatric practitioners were approached. All patients willing to participate were recruited. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethikkommission) of the Technische Universität München, Germany.

Patient data were obtained for the measure that was being developed, and this information will be reported elsewhere (Kohl S, Bühner M, unpublished manuscript, 2017). For this study, other patient information was used, including age, gender, education, diagnosis (according to the hospital records), and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores. Participants also completed questionnaires about self-stigma and aspects of clinical decision making, and their physicians rated their impression of the patients’ decision-making behavior.

Measures

Self-stigma.

Self-stigma was assessed by the five-item self-concurrence subscale of the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale–Short Form (sample item: “Because I have a mental illness, I am dangerous”) (

16). Possible scores range from 5 to 45, with higher scores indicating higher self-stigma. For our sample, the mean±SD score was 12.5±6.5 (Cronbach's α=.62). Shame about having a mental illness was rated by one self-report item (“I am ashamed to have a mental illness”) as in previous studies (

17,

18), from 1, not at all, to 9, very much. In our sample, the mean score was 4.1±2.8.

Clinical decision making.

Consumers’ participation preferences were obtained by using the Autonomy Preference Index (API), a four-item measure addressing consumers’ desire to participate in decision making (

19). Possible scores range from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater preferences for participation. In our sample, the mean score was 10.4±3.9 (Cronbach's α=.78). Communication competence of consumers in the psychiatric consultation was self-reported on three subscales of the Communication Competence Questionnaire (CoCo): adherence in communication (nine items; possible score range 9–54; sample item: “I listened very carefully to what the doctor was explaining”), critical and participative communication (nine items; possible score range 9–54; sample item: “Whenever my opinion differed from the doctor’s, I said so clearly”), and active disease-related communication (five items; possible score range 5–30; sample item: “I posed many questions regarding my treatment in general”) (

7). Higher scores on each of the three scales indicate greater competence in the respective domain. Mean scores in our sample were as follows: adherence in communication, 44.8±5.9 (Cronbach's α=.89); critical and participative communication, 39.8±7.2 (Cronbach's α=.75); active disease-related communication, 21.3±4.5 (Cronbach's α=.82).

The CoCo measure has been validated in German and covers important aspects of communication competence that have been addressed previously in English measures (

20). Critical communication, which covers several aspects of active, assertive, and self-efficacious behavior in the consultation, is regarded as a prerequisite of successful client communication. This kind of active behavior is acknowledged as helpful by a majority of physicians (

21). In addition to the CoCo as a self-report measure, we asked physicians to rate the degree of critical communication exhibited by consumers with a single item, ranging from 1, never, to 5, always. The mean score for our sample was 2.7±.9.

Locus of control.

The concept of locus of control has been linked with participation preferences, but results are inconsistent. Thus external control attribution (that is, attributing recovery to “powerful others” or “chance”) was strongly associated with lower participation preferences in one patient group, but it showed no association in another (

8). To control for this factor, we applied the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scales (

22). This questionnaire consists of four three-item subscales addressing self-control, self-blame, chance, and powerful others. According to the concept of health locus of control, clients with low external and high internal locus of control (that is, attributing changes in one’s health to one’s own behavior) are assumed to prefer more active problem solution strategies, leading to a pronounced wish for participation in medical decisions. Possible scores on each of the four scales range from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater expression in that domain. Mean scores for our sample were as follows: self-responsibility, 9.8±2.2 (Cronbach's α=.73); self-blame, 7.9±2.4 (Cronbach's α=.72); powerful others, 8.9±2.3 (Cronbach’s α=.56); and chance, 7.0±2.6 (Cronbach's α=.75).

Statistical Analysis

All scales were coded such that higher scores represented higher levels of the respective characteristic. We first assessed bivariate correlations between self-stigma, shame, and the decision-related variables (Autonomy Preference Index, CoCo subscales, and physicians’ rating of consumers’ critical communication). For variables that showed significant correlations with the three CoCo subscales or the physicians’ rating, we calculated linear regression analyses, with the decision-related variables as dependent variables and self-stigma/shame as independent variables. In all regression analyses, we controlled for age, gender, education (less than ten years versus ten years or more), diagnosis (schizophrenia spectrum versus affective disorder), GAF scores, and the locus of control subscales.

Because we had ratings for critical behavior from both clients and physicians, we then used a structural equation approach with maximum likelihood estimation (variances and loadings) to predict this construct. The model corresponds to a multiple regression with 11 independent and one dependent variable—the latent variable “critical participation.” This latent variable had two indicators (the consumer-rated CoCo subscale on critical participation and physician-rated critical participation) and corresponded to the common variance of these indicators. All analyses were performed with SPSS/AMOS. A p value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Overall, 329 participants were recruited from four inpatient (N=242) and two outpatient (N=87) sites. Of the 329 participants, 187 (57%) were female, and the mean age was 43.3±12.9. About a third (N=126, 38%) had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder), and about two-thirds (N=203, 62%) had affective disorders (unipolar depression or bipolar disorder). Higher self-stigma was associated with significantly lower communication competence (CoCo) scores and with lower physician-rated critical communication but not with participation preferences, as measured by the Autonomy Preference Index (

Table 1). Greater shame was related only to lower self-reported critical and disease-related communication.

Linear Regression Analyses

In the regression analyses (

Table 2), we controlled for age, gender, education, diagnosis, GAF scores, and the locus of control subscale scores. Better adherence in communication was associated with lower self-stigma, a diagnosis of affective disorder, and higher scores on the scale for powerful others. More critical and participative communication was associated with lower self-stigma, less shame, more self-responsibility, and less attribution of control to powerful others. No significant predictors were noted for active disease-related communication; at a trend level (p>.05), less self-stigma and less shame were related to more active communication. The physician rating of critical client behavior was associated with lower self-stigma, less attribution of control to powerful others, and more years of education.

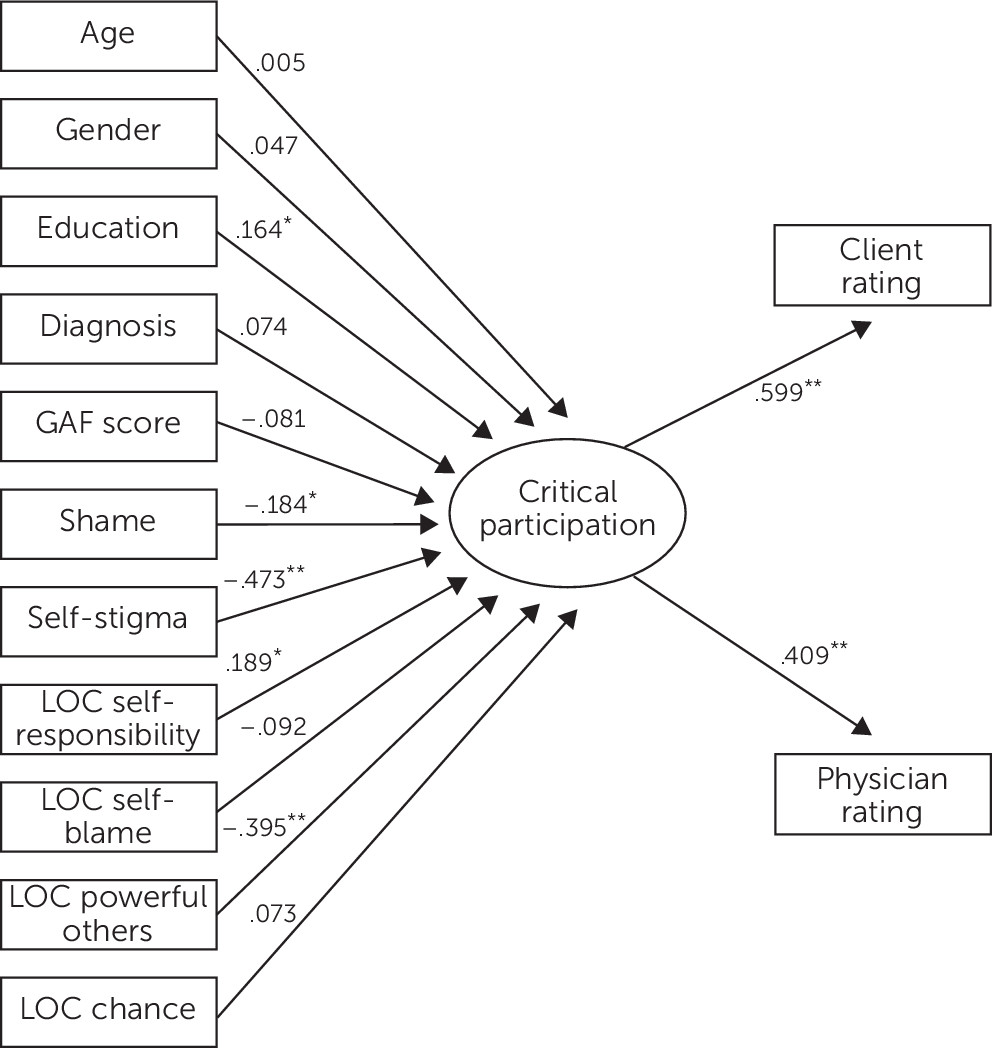

Structural Equation Approach

The latent variable “critical participation” (measured by the CoCo subscale for critical participation and by physician-rated critical participation) was predicted by more years of education, less shame, less self-stigma, more self-responsibility, and less attribution of control to powerful others (

Figure 1). Model fit was sufficient (root mean square error of approximation=.061, comparative fit index=.970) and within the guidelines proposed by Hu and Bentler (

23).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that self-stigma and shame are not related to consumers’ preferences for participation in clinical decision making. On the other hand, higher self-stigma may hinder clients’ adherence in communication (for example, their ability to pay close attention to what is discussed). In our view, the main finding is that self-stigma and shame were associated with reduced critical and participative communication. This type of communication refers to consumers’ expressing their views, daring to challenge the doctor’s opinion, and openly speaking out about disagreements (

7) and may be regarded as a prerequisite for SDM. Thus it is this area of impaired client communication competence that is most related to self-stigma and shame.

If clients suffer from self-stigma and shame, then their behavior may be less participatory and less critical, which probably leads to less SDM and more paternalistic decision making with their doctors (

24). Such a scenario may reinforce self-stigma and lead to poorer health outcomes. On the other hand, clients who interact more passively with their psychiatrists are likely to have less influence on their treatment, which may reinforce self-stereotypes (“I am incompetent”) and the “why try” effect. As noted above, self-stigma has to our best knowledge not yet been studied in the context of SDM. Thus our results add a new and potentially important aspect to the discussion that might also be relevant for patients with general medical illnesses.

Implications

Given the interdependency of self-stigma and active patient behavior and the known negative consequences for patient outcomes of self-stigma (

12) and non–patient-centered communication (

25), it seems reasonable to address these issues to improve health outcomes. Various approaches exist to reduce self-stigma and shame about having a mental illness (

26). Psychoeducational or cognitive interventions attempt to correct irrational self-stigmatizing thoughts (

27). Narrative interventions aim to increase participants’ abilities to develop positive stories about themselves and their illness, as well as their lives and achievements, that are less focused on deficits and (self-)stigma (

28). Acceptance-based programs have shown success in reducing shame among people with substance use disorders (

29). Honest Open Proud (formerly Coming Out Proud), a peer-led group intervention to support participants in making disclosure decisions, reduces stigma-related stress and self-stigma (

30,

31). Overall, however, current evidence for the efficacy of these interventions is not strong (

32). To improve SDM and to better engage consumers in medical encounters, interventions can teach physicians to communicate nondirectively, to ask about patient preferences, and to motivate them to express their preferences (

33). Other interventions can empower patients for doctor-patient interactions (

34) or offer decision support tools (

2). Effects of these interventions are small but promising (

35–

37).

Little evidence has been found regarding effects of SDM interventions on self-stigma and vice versa, but first results suggest an association between SDM and greater patient empowerment (

37). Therefore, we suggest that interventions addressing either self-stigma or patients’ behavior toward their physicians may positively influence each other and lead to better health outcomes (

11). More emphasis on these issues should be paid not only in clinical practice but also in health policies.

Limitations

Our cross-sectional data preclude conclusions about causality. Some measures were quite brief or showed low internal consistency. Finally, our analyses explain only a small proportion of the variance, which suggests that other factors—for example, personality traits or previous experiences with psychiatric treatment—may influence patient behavior in the consultation.

Conclusions

This first study of self-stigma and SDM showed that self-stigma was associated with less critical and participatory behavior of people with mental illness. Further research should address the interplay of stigma, decision making, and empowerment in more detail. Future studies should examine how addressing one of these constructs affects the others.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Kohl, M.D., for collecting the data, as well as all study participants.