Injury constitutes a major public health problem for United States civilian and military veteran patient populations (

1). Each year, approximately 30 million Americans are seen in emergency departments after injury, and approximately 1.5–2.5 million patients require hospitalization (

2). Injury is a leading cause of death among individuals under age 45 and accounts for 12% of medical expenditures in the United States (

2). Globally, injury accounts for approximately 16% of the world’s burden of disease (

3,

4).

Initial studies of trauma-exposed military veteran patients have documented an association between increasing cumulative burden of disorders and poorer health outcomes, including increased health service use and mortality (

5–

7). These investigations have identified a comorbidity cluster that includes traumatic brain injury (TBI), mental and substance use disorders, suicidality, and chronic general medical disorders.

Prior studies suggest that acutely injured civilian trauma survivors may carry a substantial burden of mental, substance use, and general medical disorders, as well as injury-related comorbidities. A series of U.S. prospective cohort investigations has suggested that between 20% and 40% of physically injured trauma survivors may develop symptoms consistent with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression after hospitalization for injury (

8,

9). Levels of posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms appear to contribute to poorer postinjury outcomes (

10). Substance use disorders are also endemic among hospitalized trauma survivors (

11). Another series of other investigations has suggested that suicide attempts and violence, including firearm-related and other assaultive injuries, frequently occur among patients presenting to U.S. acute care medical emergency department and trauma center settings (

12,

13). Patients who incur a TBI may be particularly vulnerable to recurrent violent trauma, suicidal ideation, and death (

14). Initial studies have suggested that many hospitalized survivors of traumatic injuries have preexisting chronic general medical disorders (

15).

Approximately 30 years ago, a single small-scale investigation documented an increased risk of mortality among injury survivors in the civilian population of Detroit, suggesting that traumatic injury and its sequelae could be considered a “chronic recurrent disease” (

16). The reasons that injury may be recurrent are complex and likely influenced by the constellation of comorbid mental, substance use, and general medical conditions and the lifestyle behaviors reflected in the mechanism of the index injury, such as assault or other violence-related causes (

5,

6,

17–

19). However, few population-based investigations have assessed the association between the full spectrum of mental, substance use, and general medical disorders and the risk of poor health outcomes.

This population-based retrospective cohort study first aimed to examine the frequencies of a comorbidity constellation that included mental disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and chronic general medical disorders as well as hospitalization related to violence, suicide attempts, and TBI among injury survivors. The investigation also aimed to assess the associations between the presence of these comorbidities at the time of a hospitalization for an index injury and subsequent postinjury outcomes, including recurrent hospitalization and death. It was hypothesized that a greater cumulative burden of disorders would be associated with an increased risk of recurrent hospitalizations and all-cause mortality.

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

The investigation was a population-based retrospective cohort study of all Washington State residents hospitalized for an injury during the index period of 2006–2007. All study procedures were approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board. Approval included a waiver of patient informed consent for this secondary analysis of deidentified data. Injured patients included in the cohort were identified through the Washington State Comprehensive Abstract Reporting System (CHARS) that aggregates all hospital inpatient and discharge information for the population of Washington State.

The independent variables for the study included mental disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, and general medical disorders present at the time of the hospitalization for the index injury. Additional independent variables examined included an index injury admission associated with a violent event or a suicide attempt or an index injury event associated with a TBI. The study outcomes (dependent variables) were any rehospitalization or death occurring after the index injury admission. The specific methods used to identify independent and dependent variables as well as study covariates are described below.

Mental, Alcohol and Drug Use, and General Medical Disorders

Mental and alcohol and drug use disorders were identified by review of ICD-9-CM codes in the medical record for the index admission and any other Washington State hospital admissions in the five years prior to the index injury. General medical disorders were also derived from CHARS ICD-9-CM codes. [ICD-9-CM codes for and definitions of these conditions are presented in an online supplement to this article.]

Injury Type and Severity

All inpatient hospital records for the index admission were reviewed for

ICD-9-CM codes indicative of traumatic injury. Severity of injury by body region, including TBI, was coded by using the Abbreviated Injury Scale to determine the maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale injury score and injury severity score (

20). Index hospital admissions related to injuries from firearms, assaultive violence, suicide attempts, and overdoses were identified through injury E-codes recorded in the CHARS database.

Covariates

The Washington State CHARS database contains information on patient age, sex, insurance payer status, the county of hospitalization, and the year and season of discharge. These variables were used as covariates in adjusted regression models. Race-ethnicity is not a variable included in the CHARS database.

Outcome Assessments

Hospital records for the cohort were reviewed for the five years before and after the index 2006–2007 admission; the first hospitalization for an injury occurring for each individual during 2006–2007 was identified as the index admission. The cohort was followed up until December 31, 2011, to identify recurrent hospitalization or death. Record linkage between CHARS and Washington State death records allowed for the assessment of both recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality outcomes. Probabilistic algorithms were used to link patient index hospitalization records with data for prior and subsequent hospitalizations and death records data (

21). The first two letters of the patient’s first name, the first two letters of the last name, date of birth, sex, and the first three digits of the zip code of residence were used as a subsequent set of identifiers to perform the linkage. The final database used for analyses was restricted to matches with a likelihood of accuracy of at least 99% (

21).

Statistical Analyses

First, the demographic, clinical, and injury characteristics of the cohort were documented. Next, the medical record–documented frequencies of all independent variables were assessed. Frequencies of mental disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, chronic general medical disorders, and TBI diagnoses were ascertained for the index hospitalization and for all hospitalizations in the prior five years; patterns of comorbidity were also examined. The medical record–documented frequencies of index admissions related to injuries from firearms, assaultive violence, suicide attempts, and overdoses were assessed.

The main study hypothesis was that an increasing cumulative burden of disorders would be associated with an increased risk of recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality over the five years after the index injury admission. A cumulative burden index was created that relied on yes-no counts of discrete disorders. Conditions considered for the cumulative burden index were one or more mental disorders, one or more alcohol use disorders, one or more drug use disorders, one or more chronic general medical disorders, TBI, and an index hospitalization involving an injury from a firearm, assaultive violence, a suicide attempt, or an overdose. All disorders except TBI demonstrated a significant association with poorer outcomes and were included in the index.

The study next examined the pattern of recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality over the five years postinjury. The association of each disorder with five-year postinjury recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality outcomes were ascertained, and the analysis adjusted for a single covariate: patient age.

Regression models were constructed to assess the adjusted associations between an increasing number of disorders and the health outcomes of recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality. Age, gender, payer status, injury severity, discharge year and season, and county of hospitalization were adjusted for in all regression models. Generalized estimation equation models (

22) with the negative binomial link were used to assess the adjusted association between the cumulative burden of disorders and a recurrent hospitalization; the dependent variable for these models was an annually repeated measurement of the number of recurrent hospitalizations over the five-year postinjury period. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the associations between cumulative disorder burden and all-cause mortality while adjusting for age, gender, payer status, injury severity, discharge year and season, and county.

Sensitivity analyses assessed the impact of including none, one, and two or more disorders for each disorder (rather than dichotomized yes-no variables) on the pattern and strength of the observed associations with the outcomes of recurrent hospitalization and mortality. Sensitivity analyses also assessed the robustness of the observed associations between cumulative burden of disorders and increased risk of poorer outcome by adjusting for the impact of including any history of hospitalization before the index injury admission. To assess the impact of rehospitalizations possibly related to the initial injury admission, sensitivity analyses assessed the impact of including readmissions that occurred 30, 90, and 180 days after the initial injury admission on the pattern and strength of observed associations with outcomes (

21,

23). Analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4, and Stata, version 13.

Results

In the index period, there were 76,942 patients with an injury admission (

Table 1). Approximately 79% of injured patients had one or more comorbid disorders (

Table 2). Approximately 29% of participants had one or more mental disorders. Depression was the most frequently diagnosed psychiatric disorder (14.3%, N=10,981), followed by dementia (8.4%, N=6,454). The frequency of all other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety disorders (3.9%, N=2,994) and PTSD (2.4%, N=1,830), was less than 5% in the cohort. Twenty-five percent of patients were diagnosed as having alcohol abuse or dependence. Approximately 2.0% (N=1,507) had marijuana abuse or dependence, 3.7% (N=2,877) had stimulant abuse or dependence, and 2.6% (N=2,022) had opiate abuse or dependence. Sixty-two percent of patients had one or more chronic general medical disorders. The most frequently diagnosed general medical disorder was hypertension (33.7%, N=25,931), followed by ischemic heart disease (24.1%, N=18,540), pain-related disorders (21.9%, N=16,871), pulmonary disorders (16.4%, N=12,613), diabetes (14.2%, N=10,887), cerebrovascular disease (7.2%, N=5,565), renal disease (5.6%, N=4,341), and liver disorders (5.1%, N=3,911). All other disorders were diagnosed among less than 5% of hospitalized injury survivors.

Mental and substance use disorders frequently occurred as comorbid conditions. For example, 99% of patients with a diagnosis of a drug use disorder (N=16,198 of 16,387) had one or more comorbid mental, alcohol use, or chronic general medical disorders or TBI. Similarly, 95% of patients with a diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder (N=18,173 of 19,167) and 89% of patients with a diagnosis of a mental disorder (N=19,691 of 22,062) had one or more comorbid disorders.

In age-adjusted analysis, patients with all disorders except TBI had a significantly increased risk of recurrent hospitalization and death (

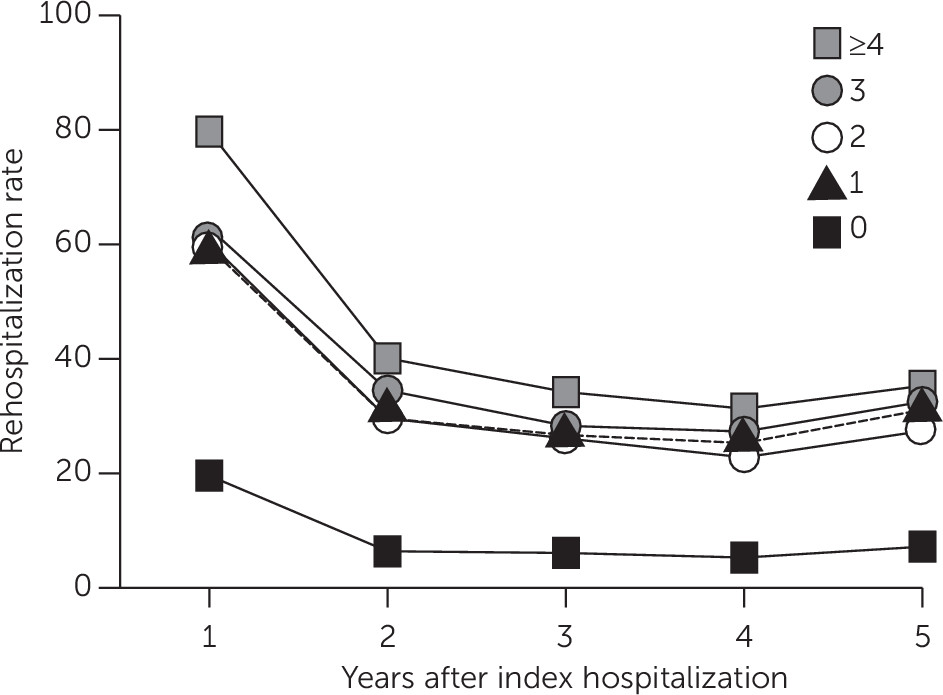

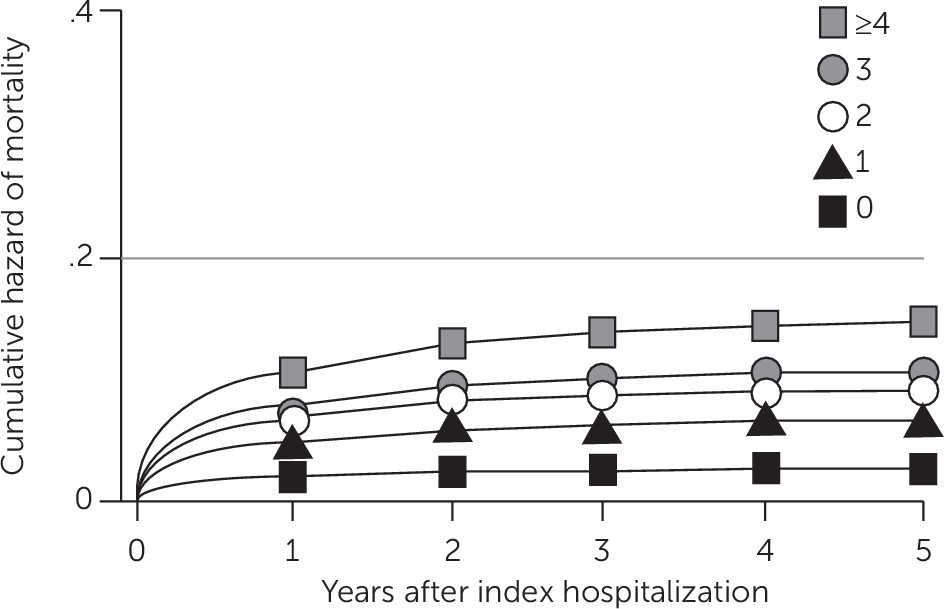

Table 2). After adjustment for age, patients with a greater cumulative burden of disorders demonstrated a pattern of greater risk of recurrent hospitalization and death over the five years after the index injury admission (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

In regression models that adjusted for age, gender, payer status, injury severity, county of hospitalization, and discharge year and season, a greater number of disorders was associated with an increased risk of recurrent hospitalization (

Table 3). These associations manifested in a dose-response pattern such that the addition of a single disorder increased the risk in an incremental graded manner. Cox proportional hazard models that adjusted for age, gender, payer status, injury severity, county of hospitalization, and discharge year and season showed a similar dose-response pattern such that a greater number of disorders was associated with incremental increases in the risk of mortality (

Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses that coded disorders as none, one, and two or more did not substantially alter the magnitude, pattern, or significance of the observed associations for recurrent hospitalization or all-cause mortality. Similarly, analyses that varied the number of days assessed after the index injury hospitalization (that is, 30, 90, or 180 days) did not substantially alter the pattern or magnitude of the observed associations for recurrent hospitalization. Finally, including prior hospitalizations in the regression models did not modify the dose-response pattern but weakened the strength of the observed associations for recurrent hospitalization (four or more conditions, relative risk=2.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.17–2.45) and all-cause mortality (four or more conditions, hazard ratio=3.90, CI=3.44–4.42).

Discussion

This investigation corroborates and extends observations from prior studies and suggests that a broad profile of mental, substance use, and general medical disorders, as well as violent and suicide-related events, frequently occur among injury survivors in the civilian population (

9,

11,

15,

16). As shown in this study, mental and substance use disorders rarely occurred in isolation after an injury, and these disorders were comorbid in most patients.

This large-scale population-based investigation also demonstrated the remarkable heterogeneity of mental, substance use, and chronic general medical diagnostic presentations after injury. A literature review showed that few large-scale investigations had documented a broad spectrum of highly prevalent chronic general medical disorders among injury survivors, including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, pain-related disorders, pulmonary disorders, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, and liver conditions. This heterogeneity was further complicated by hospital admissions related to violent events, suicide attempts, and overdoses. Few prior investigations have considered combining these multiple heterogeneous disorders into a single comorbidity index for injured civilians.

This is the first population-based investigation among civilians to demonstrate a dose-response relationship between the cumulative burden of mental, substance use, and general medical disorders and poor health outcomes after an injury hospitalization. The health outcomes assessed included recurrent hospitalization and all-cause mortality over the five years after an injury admission. Studies of trauma-exposed veterans have suggested a similar dose-response relationship between poorer health outcomes and the cumulative burden of mental, substance use, and general medical conditions and TBI, including increased health service utilization and death (

5,

6).

In this investigation, TBI did not contribute to poorer health outcomes after the index injury admission. Prior investigations documenting poorer health outcomes among survivors of TBI have used control samples from the general population or of noninjured persons (

5,

14). Future research could explore the possibility that among hospitalized patients with multiple physical injuries, TBI alone may not increase the risk of recurrent hospitalization or death.

This investigation had a number of important limitations. The study used a large administrative database to ascertain diagnoses of mental disorders, alcohol and drug use disorders, other injuries, and general medical conditions. Assignment of diagnoses relied on diagnostic codes that frequently derived from assessments by acute care medical providers rather than expert diagnostic interviews. In addition, information derived from outpatient visits is not included in the CHARS data, which may have affected the accuracy of specific ICD-9-CM diagnostic categories in the investigation. Also, the administrative database did not contain a variable identifying patients’ racial or ethnic group status.

ICD-9-CM codes related to injury severity were missing for approximately 10% of patients. This may have resulted in underestimates of the number of patients in the study with a diagnosis of TBI and may explain why patients with TBI did not demonstrate a consistent pattern of worsening outcomes in univariate and minimally adjusted analyses. In addition, the investigation did not account for individuals who were injured during the index period but who were not residents of Washington State.

The study did not employ a preexisting comorbidity index to assess injured patients’ risk of recurrent hospitalization and death. Some of the conditions endemic among trauma survivors are captured by commonly employed and validated indices; however, many conditions are not, including PTSD, violent events, suicide attempts, and TBI (

24). As with initial studies of returning veterans (

5–

7), the approach used in this study aimed to include conditions unique to injured civilians. Future research could productively explore the creation of comorbidity indices tailored to the unique constellation of conditions endemic to injured patients.

Finally, this study assessed longer-term outcomes, including recurrent hospitalization over a five-year period; it did not focus intensively on 30-day readmission rates. Systematic investigation has begun of unplanned readmissions after surgery for general medical conditions and traumatic injuries; however, these investigations have tended to focus on short-term outcomes, such as 30-day readmission rates (

25,

26).

Beyond these considerations, the results have important implications for the detection and treatment of injured patients with comorbid mental, substance use, and chronic general medical disorders, as well as for patients with admissions related to violent events and suicide attempts. Prior investigations have documented shortcomings in the quality of postinjury psychiatric screening and service coordination (

27). Commentary from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other organizations suggests that screening and intervention procedures should be developed for the increasing number of Americans who have multiple chronic conditions. The results of this study suggest that screening and intervention development could productively focus on multiple chronic disorders among survivors of traumatic injuries (

27,

28). Screening and intervention development could target both the prevention of the onset of new disorders (for example, chronic PTSD in the wake of an injury hospitalization) and the mitigation of the impact of an injury hospitalization on preexisting chronic conditions (for example, hypertension and diabetes) (

18).

Conclusions

Ultimately, population-based surveillance procedures that incorporate pragmatic trials of real-time, workflow-integrated screening and stepped care interventions targeting the full spectrum of posttraumatic comorbidity clusters could be developed and implemented. One recent investigation used automated screening for

ICD-9-CM codes in electronic medical records to recruit patients and found that approximately two-thirds of hospitalized injured patients had one or more chronic general medical disorders (

29). Future pragmatic trials could test broadly targeted automated screening algorithms and intervention strategies facilitated by computerized decision support tools (

28,

30). A series of investigations has suggested that collaborative care intervention models may be optimal intervention strategies for targeting the multiple chronic disorders that afflict survivors of traumatic injuries (

27,

29). Collaborative care intervention models productively combine care management that targets both the injury and the general medical conditions with evidence-based interventions for comorbid mental and substance use disorders. Measurement-based stepped care procedures allow collaborative care teams to systematically target multiple disorders over the weeks and months postinjury. Orchestrated investigative and policy efforts could systematically introduce and evaluate screening and intervention that broadly target the full spectrum of comorbid disorders afflicting hospitalized injured patients at U.S. trauma centers (

31).