In the United States, increasing numbers of people with an illness or disability rely on informal caregivers, most of whom are family members or friends. By 2015, an estimated 18% of the adult population, or 43.5 million Americans, were informal caregivers (

1), and 8.4 million provided assistance to a person with an emotional or mental health issue (

1). Although informal caregiving is essential to supporting the care recipient’s health and well-being (

1), it often takes a personal toll on the caregiver. In a 2015 national survey of informal caregivers, three-fourths reported stress symptoms and four in ten found it difficult to manage their own health (

2).

This study addressed psychological distress among informal caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Typically diagnosed when a person is between 16 and 30 years of age, these disorders are life changing and generally persist into adulthood (

3).

Research on informal caregivers has found that problems such as stress, anxiety, depression, and a decreased sense of well-being are prevalent (

4–

8). Studies also have shown that mental health tends to be worse among certain caregivers. These include female caregivers as well as those who assist a person whose illness is more chronic (

9), perceive that the person receiving care poses a risk to self or others, are parents of adolescents or young adult children with the illness (

10), regard the illness as highly stigmatized (

11), appraise caregiving in a negative manner, and have an avoidant coping style (

12). A great deal of this prior research has addressed family caregivers (

13–

16).

This study included a large population-based sample of informal caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or both. Its aims were to quantify the degree of psychological distress among these caregivers and, guided by an established stress model, to identify the main correlates of this distress. The study is distinct from prior research in terms of the diversity of informal caregivers included, large sample size, broad range of variables considered, and statistical methods.

Psychological distress generally refers to a mental health problem characterized by a range of cognitive, emotional, and physical symptoms and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality (

17,

18). According to the Lazarus and Folkman transactional model of stress and coping (

19), stress is the result of a process whereby certain life events or experiences may be perceived by an individual as potentially threatening or harmful (primary appraisal), triggering a reaction (a secondary appraisal) that influences how the person copes with the perceived threat or harm. Elaborating on this model, Pearlin and colleagues (

20) suggested that caregiver distress is the result of the hardships involved in the caregiving role as well as social roles other than caregiving. Stress is different from caregiver burden, another frequently studied outcome. Generally, burden refers to a composite of the objective tasks of the caregiving role and subjective evaluations of the role. The former model regards tasks as potential stressors, separate from the psychological outcome (

21).

Thus, based on the transactional model of stress and coping, this study tested the following three hypotheses: first, informal caregivers’ psychological distress is multidimensional, influenced by the individual characteristics of caregivers and care recipients, social role demands, social supports, and appraisals of caregiving; second, social supports moderate the effects of demands on distress; and third, cognitive appraisals of caregiving mediate the effects of demands on distress.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was administered between December 15, 2014, and April 30, 2015, by using REDCap software on a privacy-protected Internet Web site. Protocols were approved by the Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (protocol 11457).

On the basis of research by Donelan and colleagues (

22), an eligible informal caregiver was defined as a caregiver of a person diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or both, who provided unpaid help in the past 12 months to a relative or friend (or arranged for such help), including assisting with household chores, finances, and personal or medical needs. Eligible caregivers had to be at least 21 years old and able to read and speak English.

Recruitment advertisements were disseminated in collaboration with mental health advocacy organizations and the media. Electronic or print advertisements were released by the following individuals or groups: Jeanne Phillips, author of the nationally syndicated Dear Abby column; Mental Health America; the National Psychosis Prevention Council; the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and NAMI Massachusetts; the Schizophrenia and Related Disorders Alliance of America; and Reddit’s caregiver group.

The study Web site posted information about procedures, security, and consent, along with a toll-free phone number. After endorsing the “consent to participate” box, each potentially eligible participant advanced to screening questions and, if eligible as determined by the screening, to the approximately 30-minute-long anonymous questionnaire. No incentives were provided, and the study did not collect information from nonconsenting or ineligible persons.

The primary outcome was caregiver psychological distress measured with the ten-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which is a validated global measure of psychological distress with demonstrated scale reliability, internal consistency, construct validity (

23), and sensitivity to differences in group stress levels (

24). PSS scores range from 0, no distress, to 39, highest level of distress (U.S. female norm=13.7±6.6; U.S. male norm=12.1±5.9 [

23]). The PSS was chosen over caregiving burden measures such as the Zarit Burden Interview (

25,

26) because, although both meet psychometric criteria, the PSS has better face and content validity as a measure of psychological distress. Generally, in caregiver burden scales, the indicators of the psychological consequences of caregiving are combined with, not separate from, potentially explanatory variables (for example, demands and appraisals) (

6,

7,

27).

Four groups of independent variables were collected. Group 1 variables included caregiver and care recipient characteristics: age, relationship (for example, parent), gender, education, caregiver health (number of chronic conditions), caregiver location (urban, suburban, or rural), care recipient diagnoses, and care recipient residence (for example, own home). Group 2 variables accounted for demands on the caregiver: primary caregiver (versus secondary or caregiving shared equally), amount of caregiving provided in the past 12 months (all, most, some, a little, or none), demands related to illness and medication management (for example, frequency of hospitalizations in the past 12 months, concern with medication discontinuation, and confidence in medication effectiveness), other social roles (for example, employment and married or cohabitating), and demands as assessed by the Family Experience Interview Schedule (FEIS) (

28). Demands included the frequency of assisting with specific activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs (IADLs), for which the total possible score range is 0–32, and the frequency of monitoring for specific behaviors, for which the total possible score range is 0–28. The FEIS generally is scored to reflect the frequency of providing assistance with each demand and how much of a “bother” it is. This study’s FEIS summary scores multiplied each endorsed demand by the frequency with which it was performed. [More information is presented in an

online supplement to this article.] The “bother” variable was excluded from the score to minimize overlap with the dependent variable (PSS score).

Group 3 variables included coping resources and supports: personal income and the availability of social supports (for example, has access when needed to a substitute caregiver, caregiving advice, medical advice, help with legal matters, help with financial matters, and advice on community services) (no support, 0; maximum support, 100). Neither affective support nor network attributes were measured. Group 4 variables included cognitive appraisals of caregiving: perceives caregiving as financially burdensome or emotionally unrewarding. The study did not include separate measures for primary and secondary appraisals. Each appraisal item score was on a scale from 0, least negative, to 100, most negative.

Survey data were checked for missing values, out-of-range values, logical consistency, and scale reliabilities (that is, Cronbach’s alpha statistics). Descriptive statistics, such as variable means and SDs, frequencies, and percentages, were computed [see online supplement]. First, the association with distress of the four groups of variables specified in the transactional stress model (hypothesis 1) was tested with univariate methods. Statistically significant predictors (p≤.05) were retained for final testing in structural equation models (SEMs).

Next, the moderating effects of social supports on distress were tested (hypothesis 2). With use of multivariate models, the PSS score was regressed simultaneously on all group 2 variables (demands) and group 3 variables (coping resources and supports) as well as their interaction terms, adjusting for group 1 variables (individual characteristics). To optimize the statistical power for the number of interaction tests and adjust for multiple comparisons, an overall F test and a 1-degree-of-freedom approach (

29) were used. The latter compensates for the risk of missing a statistically significant association in an overall F test [see

online supplement].

The next step evaluated whether cognitive appraisals of caregiving mediated the effects of demands on distress (hypothesis 3). Variables tested in the univariate model of distress were retested separately as predictors of cognitive appraisals of financial burden and cognitive appraisals of rewards. Mediation tests required that the cognitive appraisals predicted PSS scores and that variables predicting PSS scores also predicted one or both cognitive appraisals.

Finally, once the prior steps were completed, a comprehensive SEM was estimated (

30,

31) in three regression equations. The first equation regressed cognitive appraisals of financial burden on the set of statistically significant predictors simultaneously. Similarly, the second equation regressed cognitive appraisals of unrewarding caregiving on the same predictors. The third equation regressed the PSS score on the cognitive appraisals and the same set of predictors plus any others that were significantly related only to the PSS score in the univariate analyses. SEM results are reported as each variable’s unstandardized direct, indirect (mediated), and total effects on distress as well as model fit statistics [see

online supplement]. Independent variables were assumed to be measured without error.

Results

Of 2,338 Web site “hits,” 1,708 individuals consented to participate and 1,398 were eligible caregivers [see figure in online supplement]. Of these, 19 were excluded for missing data (final N=1,142).

Most of the caregivers were women (83%), white (89%), and college-educated (59%) (

Table 1). The mean age was 55.6, and most (82%) had at least one chronic health problem (mean=2.2±2.0). Most caregivers were a parent (60%). In 41% of cases, the caregiver lived with the care recipient.

Most care recipients were male (66%) and white (85%) and had completed high school (29%) or attended some college or completed college (56%) (

Table 1). The mean age was 40.2. According to caregiver reports, 33% of care recipients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 26% had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and 38% had both diagnoses; 4% of caregivers did not know the diagnosis or did not respond. In 23% of cases, the diagnosis was made within the past five years. Nearly half (45%) of the care recipients had been hospitalized at least once in the past year. Approximately one-third (35%) of the caregivers were very or extremely concerned about medication discontinuation, and 27% had little or no confidence in the medication’s effectiveness.

Regarding demands on caregivers, 75% had primary caregiving responsibility, and 72% provided all or most of the care (

Table 1). Between 40% and 61% (data not shown) provided assistance with ADLs or IADLs at least weekly (mean intensity=13.9±8.5). Between 12% and 39% (data not shown) of the caregivers were involved in monitoring behavior on a weekly basis or more often (mean intensity=5.5±5.4). In addition to caregiver role demands, most caregivers were married or living with a partner (69%) and employed (62%).

The availability of social supports was limited (mean=32.7 out of 100). Caregiving generally was perceived as a moderate to large financial burden (mean=62.0 out of 100) and moderately to highly emotionally unrewarding (mean=52.8 out of 100). Mean psychological distress as measured by the PSS was 18.9±7.1.

In univariate regression models predicting psychological distress, variables from each of the four groups were statistically significant (

Table 2). Caregivers with relatively higher distress were younger (p≤.001), resided in urban areas (p=.05), had a greater number of chronic health problems (p≤.001), assisted care recipients who were young (p≤.001) and more recently diagnosed (p≤.01), were employed (p≤.001), were the primary caregiver (p≤.01), performed a large portion of the caregiving (p≤.001), assisted with medication issues (concerns about medication discontinuation and effectiveness, each p≤.001), assisted care recipients who had had recent hospitalizations (p≤.001), regularly helped with ADLs and IADLs and monitoring behavior (each p≤.001), had minimal social support available when needed (p≤.001), and viewed caregiving as financially burdensome (p≤.001) and lacking in emotional rewards (p≤.001).

In models using each cognitive appraisal as the dependent variable (

Table 2), results were similar to those for the PSS, except that caregiver age, location, and employment were not significantly related to either appraisal. Furthermore, social support did not significantly modify the effects of the demand variables on distress (overall 1-degree-of-freedom test p=.263) [see

online supplement].

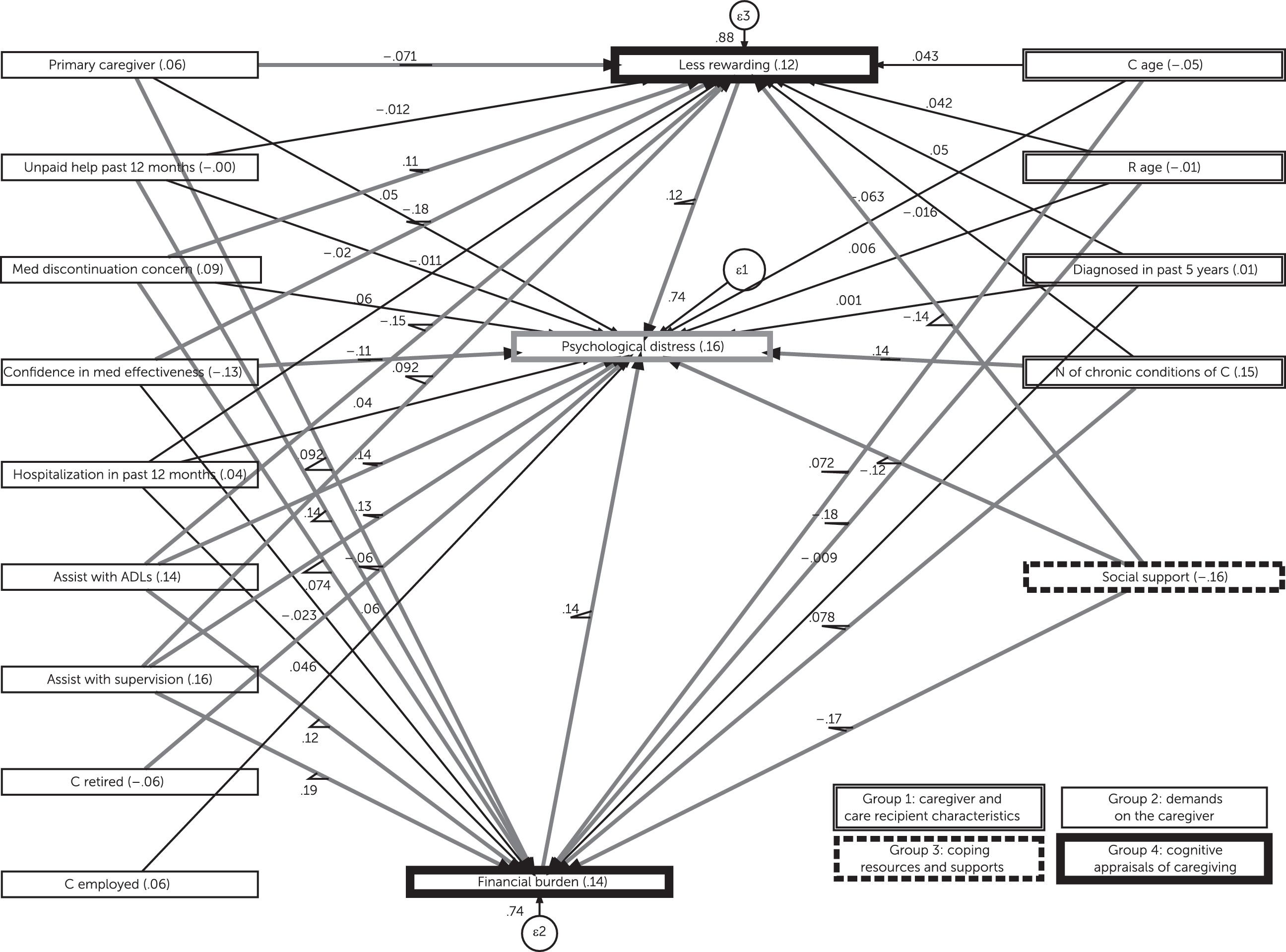

The SEMs confirmed the influence of each of the four stress model components, as well as the partial mediating effects of cognitive appraisals of both financial burden and emotional rewards [see

online supplement]. The direct effects of variables in the models were larger than the indirect effects. For example, caregiver health had a standardized direct effect of .14, an indirect effect of .01, and a total effect of .15. As shown in

Figure 1, total standardized effects were highest for the following variables: social support (–.16), frequency of monitoring behavior (assist with supervision) (.16), caregiver health (number of chronic conditions) (.15), appraisals of financial burden (.14), frequency of assisting with ADLs or IADLs (.14), confidence in medication effectiveness (–.13), appraisals of low emotional rewards (.12), and concern about medication discontinuation (.09). The SEMs met two of the three fit criteria [see

online supplement].

Discussion and Conclusions

This study had three main findings. First, psychological distress among informal caregivers as measured by the PSS was high (18.9±7.1 out of 39). It was 5.5 points higher than the U.S. norm (mean U.S. norm weighted for gender=13.4±6.5) and 3.0 points higher than the mean for survivors of the Hurricane Sandy disaster (15.6±7.3). In the Hurricane Sandy sample, 30% of participants were categorized as high stress (mean ≥20) (

32), compared with 48% in this sample.

Second, supporting the transactional stress and coping model, results suggest that caregiver distress is related to several different variables. Of specific importance was the relationship of distress to role demands, which had both a direct effect on distress and indirect effects through more negative appraisals of financial and emotional hardship. Specifically, the amount of time and effort devoted to caregiving (for example, assisting with ADLs and IADLs) contributed to distress, as did two additional indicators of demand: risk of medication discontinuation and concern about medication effectiveness. These results suggest that tasks related to managing treatment and symptoms are significant stressors.

Third, study results provide insights into the possible mechanisms underlying the effects on distress of cognitive appraisals and social supports. Negative cognitive appraisals of caregiving increased distress, although their direct effects on distress were stronger than their mediating effects. Negative appraisals were associated with managing more demands, being a relatively younger caregiver, assisting someone with a more recently diagnosed illness, and having less social support available. Although social supports, measured as perceived availability when needed, did not moderate the effects of demands, they contributed both to distress and negative appraisals.

Interventions addressing these mechanisms and their determinants could play a part in preventing caregiver distress. Prior intervention research has demonstrated the feasibility of modifying distress through interventions specific to the early stage of illness, family systems approaches, augmentation of specific skills (coping), and provision of resources (for example, information through psychoeducation and social supports) (

32,

33). Study results generally support these approaches, although neither a care recipient’s recent diagnosis nor a recipient’s younger age had strong direct associations with distress. Study results also suggest the importance of targeting two potentially modifiable variables: cognitive appraisals of caregiving and social supports. For example, on the basis of SEM coefficients that considered all variables simultaneously, complete elimination of the caregiver’s subjective evaluation of financial burden could conceivably reduce distress by 1.86 points. Helping caregivers feel more emotionally rewarded in this role could lower distress another 1.06 points. Maximizing the availability of social supports could achieve another 3.36-point decrease. These changes would close the gap in distress between caregivers and the U.S. population norm.

This study benefited from a large and diverse sample, comprehensive measurement using validated scales, and a careful statistical analysis of the stress process, including attention to potential sources of bias. Study limitations included the absence of a coping scale, separate primary and secondary appraisal variables and a duration-of-caregiving indicator, use of single variables to capture complex concepts (for example, appraisals), as well as use of cross-sectional data, convenience sampling, and self-report methods only. Compared with similar U.S. caregiver studies, this study’s sample was slightly older and had a higher percentage of married participants (

34–

36). The sample also had a high percentage of white, female caregivers, and because of the absence of representative data on the entire caregiver population, it is not clear how these characteristics reflect those of the average caregiver. Also, although the PSS is validated, it may capture some sources of distress unrelated to caregiving. For example, the effect of caregiver health status on distress may reflect greater difficulty performing caregiving tasks or an emotional reaction to poor health, or both.

Despite some shortcomings, results provide new information regarding the complexity of caregiver distress, including the multiple variables involved in determining the caregiver’s mental health outcome. This study also contributes further evidence of the potential value of providing interventions to address caregiver health, caregiving demands, financial burdens and emotional rewards, and access to social supports.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Doris Hernandez for assistance in manuscript preparation and Annabel Greenhill for assistance preparing the survey in electronic form and monitoring responses. They also acknowledge Xiaoying Wu for assistance in creating the figure.