Medicaid is a joint program between the states and federal government that provides health insurance coverage to certain low-income populations. In 2014, funding for Medicaid exceeded $498 billion (

1). In that year, approximately 85.9 million people, or 27% of the U.S. population, was covered by Medicaid for at least one month (

2).

Medicaid coverage is critical for low-income individuals diagnosed as having cancer. In addition to providing coverage for cancer treatments, Medicaid also covers certain supportive and palliative care services for Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer, including mental health care services. Among individuals with cancer, access to mental health care services is particularly important. Cancer survivors are more likely to use mental health services compared with individuals who have not received a cancer diagnosis (

3). A large meta-analysis reported that among adults diagnosed as having cancer, the prevalence of depression was 24.6% and the prevalence of anxiety disorder was 9.8% (

4). Among persons with cancer, rates of mental health conditions may be even greater among Medicaid beneficiaries than among individuals with private insurance or Medicare, given that Medicaid beneficiaries often do not have the same level of financial and social support to help provide resilience during and after cancer treatment (

5–

8). In addition, dual Medicaid-Medicare enrollees with cancer have significantly lower mental health–related quality of life compared with enrollees with Medicare only (

9). Furthermore, mental health comorbidities can substantially increase the cost of care for Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer (

10).

Although all state Medicaid programs provide coverage for mental health services, that does not guarantee access to care for Medicaid beneficiaries. That is particularly true for mental health services; for example, acceptance of Medicaid patients among psychiatrists is significantly lower than Medicaid acceptance by other physician specialties (

11). This may reflect lower reimbursements provided by Medicaid for mental health services, and psychotherapy in particular (

12). In addition, each state sets policies for its own Medicaid program, including reimbursements for health care providers and services. Consequently, there is substantial variation across states in Medicaid reimbursements to health care providers for a range of medical services, including mental health care services (

13). Golberstein and colleagues (

14) reported variations across states in use of mental health services among Medicaid beneficiaries. However, the study did not examine differences in state-level Medicaid policies that likely affect willingness of mental health professionals to offer services to Medicaid beneficiaries. In other clinical areas, previous research has demonstrated that lower Medicaid reimbursements are associated with decreased receipt of medical care or delays in accessing needed care (

15–

19). Other state-level policies, such as required patient copayments, can also decrease receipt of medical services among Medicaid beneficiaries (

20,

21).

Little is known regarding the impact of state-level Medicaid policies on receipt of mental health services among Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer. This study used national Medicaid claims data from individuals diagnosed as having breast cancer to examine the impact of state-level policies on receipt of mental health diagnostic and treatment services. The study had the following three hypotheses: increased Medicaid reimbursement for consultations (requests from one health care provider to another for advice regarding evaluation or management of a specific problem) or for provision of mental health services will be associated with increased receipt of mental health services in the study population (hypothesis 1), copayments required from Medicaid beneficiaries for health care services (including mental health services) will be associated with decreased receipt of mental health services in the study population (hypothesis 2), and having more comorbidities will be associated with increased receipt of mental health services in the study population (hypothesis 3).

Methods

Study Data and Population

This analysis used 2006–2008 Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) claims and enrollment data to examine associations between three types of Medicaid policies (reimbursements, required patient copayments, and requirements governing the timing of Medicaid eligibility recertification [eligibility recertification period]) and receipt of mental health diagnostic services and mental health treatment services among Medicaid beneficiaries with breast cancer. Study data were collected prior to implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and, therefore, represent treatment patterns and policies that were not affected by the ACA. The study population consisted of individuals who were ages 18–64, enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid, and diagnosed as having breast cancer. Because cancer registry data linked to Medicaid claims data were not available, claims were used to identify cancer diagnoses. To identify beneficiaries with breast cancer, we relied on previously published studies that classified Medicaid beneficiaries as having breast cancer using two criteria (

22–

24). First, beneficiaries were required to have at least two Medicaid claims with an

ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for breast cancer (174.x, 233.0, 238.3, or 239.3) dated at least 30 days apart. In addition, beneficiaries were required to have a subsequent claim with a procedure code for a breast cancer–specific surgery. This included mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery (BCS). Mastectomy was identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 19160, 19162, 19180, 19182, 19200, 19220, 19240, or 19303–19307;

ICD-9 procedure code 85.4x; or diagnosis-related group (DRG) code 257 or 258. BCS was identified by CPT code 19120, 19125, 19126, 19301, or 19302;

ICD-9 procedure code 85.20, 85.21, 85.22, or 85.23; or DRG code 259 or 260. The list of surgical procedures does not include codes for biopsy only. Receipt of a biopsy in the absence of subsequent surgical resection may indicate a “rule out” for breast cancer and thus, by itself, is not sufficient evidence of a cancer diagnosis.

Dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollees were excluded from the study population, given that their complete service utilization may not be reported in MAX. Beneficiaries in capitated managed care plans were also excluded, given that Medicaid reimbursements, a key independent variable for this study, are not included in their claims data. Because beneficiaries with limited duration of Medicaid enrollment (for example, those who lost Medicaid eligibility shortly after enrolling in Medicaid) are less likely to have an opportunity to seek mental health care services, beneficiaries with less than four months of enrollment were excluded. Beneficiaries who were pregnant or resided in a long-term-care facility were excluded.

The study population analyzed for receipt of diagnostic mental health services was limited to states where at least one Medicaid beneficiary with breast cancer had claims for diagnostic mental health services, given that reimbursement rates for these services could not be determined for states without any such claims. Similarly, the study population for analyses of mental health treatment services included patients only in states with at least one Medicaid beneficiary with breast cancer having a mental health treatment claim. Analyses separately examined predictors of receipt of mental health diagnostic and treatment services. For analyses of the receipt of mental health diagnostic services, Medicaid data from 43 states were included. For analyses of receipt of mental health treatment services, Medicaid data from 45 states were included.

Study Outcome Measures

We evaluated the association between demographic characteristics and Medicaid policies with receipt of mental health services, including mental health diagnostic services and mental health treatment services. Mental health diagnostic services were identified by CPT code 90801 (psychiatric diagnostic interview), 90802 (interactive psychiatric diagnostic interview), or 96101–96120 (psychological testing). Mental health treatment services were identified by CPT codes 90804–90857 (psychotherapy) and 90862–90889 (other psychiatric services). Both mental health diagnostic and mental health treatment services may be provided by physicians or by other health care providers, depending on state license requirements, Medicaid policies, and scope-of-practice regulations.

Study Independent Variables

The main independent variables of interest were state-level Medicaid policies. Medicaid reimbursements for mental health services were determined as the state- and year-specific median reimbursement for the mental health diagnostic and treatment CPT procedure codes listed above. In addition, we included state- and year-specific median Medicaid reimbursement for consultations (CPT 99243), given that a consultation may represent the initial interaction between a mental health professional (a physician or a nonphysician health care provider) and a patient seeking mental health care services.

Two other year-specific, state-level Medicaid policies were also included as predictor variables: whether a patient copayment was required for medical care services (including mental health services) and whether recertification of Medicaid eligibility was required once every 12 months or at more frequent intervals, given that the eligibility recertification period may affect continuity of care (

25–

27). Other independent variables included race-ethnicity (black, Hispanic, white, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, or other/unknown), age at cancer diagnosis, comorbidities score (Charlson Index, excluding cancer diagnosis, with the Deyo et al. [

28] modification), and Medicaid eligibility category (blind/disabled, medically needy, enrolled due to breast cancer, or other). In regression analyses, race-ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white vs. all other. In addition, to control for differences in costs of medical care and the relative generosity of state-level Medicaid reimbursements, average annual medical care costs for each state were also included as an independent variable.

Data Analytic Procedures

We performed generalized estimating equations to assess factors influencing receipt of mental health services while controlling for clustering of participants by state (that is, the models include a state fixed effect). Separate models were derived for each outcome (receipt of mental health diagnostic or mental health treatment services). Analyses were performed by using PROC GENMOD in SAS, version 9.3, with a logit link function and an independence correlation structure. Study procedures were approved by the RTI International Institutional Review Board.

Discussion

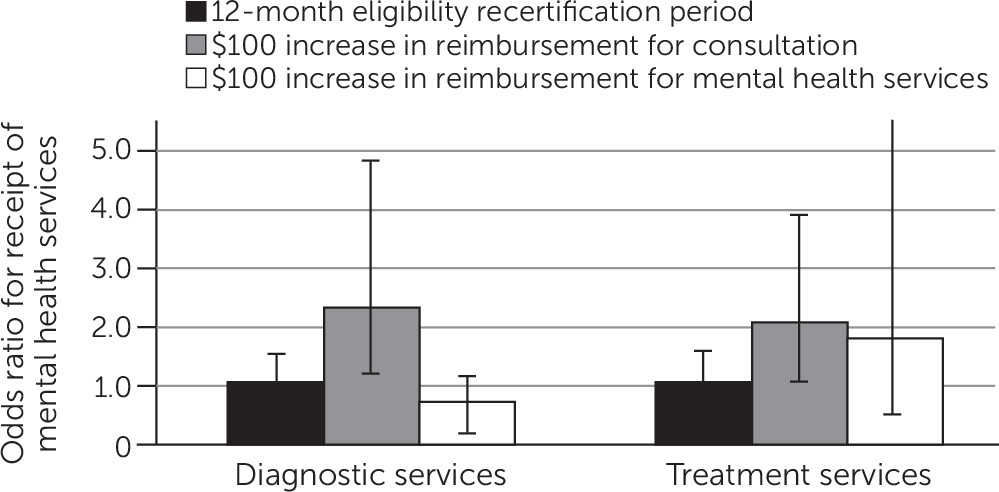

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining factors influencing receipt of mental health care services among Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed as having breast cancer. Related to study hypothesis 1, we found that increased state-level Medicaid reimbursements for consultations were associated with increased likelihood of receiving mental health diagnostic and treatment services, but increased reimbursements for mental health services were not significant predictors of their use. This may suggest a gatekeeper effect; that is, a consultation was needed prior to receipt of mental health services, but once a beneficiary received this consultation, low reimbursement for mental health diagnostic or treatment services was not a barrier. There are several potential explanations for this effect. For example, once a patient is identified as needing mental health services through a consultation, a health care provider may feel a duty to offer those services despite their low reimbursement. Alternatively, the individual performing the consultation might not be the same provider performing the mental health services. Further research is needed to determine if a gatekeeper effect is present. An analysis of state-level policies affecting cancer screening among Medicaid beneficiaries reported similar findings: increased reimbursement for physician visits was significantly associated with increased likelihood of cancer screening, but reimbursements for the screening tests were not significant predictors of cancer screening (

21).

Increased Medicaid reimbursements for consultations may increase the likelihood that a psychiatrist will provide consultations for Medicaid beneficiaries. Previous studies have documented that individuals with Medicaid coverage experience multiple barriers to receiving mental health services. For example, only 43.1% of psychiatrists accept Medicaid compared with 73.0% of physicians with other specialties (

11). In addition, shortages among psychiatrists likely limit their availability for Medicaid beneficiaries; this shortage is projected to worsen, given that more than half of psychiatrists are over age 55 (

11). Recent data indicate that the number of practicing psychiatrists decreased between 2003 and 2013 (

29).

Required patient copayments were not significantly associated with the likelihood of receiving mental health services in the study population (hypothesis 2). In a previous study, requiring copayments from Medicaid beneficiaries was generally associated with decreased receipt of cancer screening (

21). Similarly, Medicaid beneficiaries in states that did not require copayments for tobacco dependence counseling or pharmacotherapy were more likely to successfully quit smoking (

30). However, among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, required medication copayments (for generic or branded drugs) had mixed associations with medication continuity (

31). In that study, higher medication copayments were significantly associated with medication continuity only for generic drugs and only among the schizophrenia cohort; there was no association between higher medication copayments and medication continuity for generic or branded drugs among the bipolar disorder cohort. The effects of copayments among Medicaid beneficiaries with psychiatric diagnoses is not well understood.

Increased comorbidities were associated with increased receipt of mental health services (hypothesis 3). This may reflect the association between general medical comorbidities and mental illness; individuals with multiple comorbidities are more likely to experience mental health conditions (

32–

34). More research is needed to better understand this finding.

Access to mental health services is particularly important for individuals diagnosed as having cancer. Multiple reports have documented that individuals with cancer are at increased risk of distress (

35–

38). Distress has been defined by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (

39) as “unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that might interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment.” Appropriate treatment of distress may enhance quality of life as well as clinical cancer outcomes (

35). The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer requires accredited cancer programs to include distress screening as part of standard oncology care (

40). In addition, results of the distress screening must be discussed with the patient, and if moderate to severe distress is present, a member of the patient’s oncology team must assess the patient to identify the cause of the distress (

40). Distress and other mental health issues may require individuals with cancer to seek diagnostic and treatment services from mental health professionals. Because many oncology practices do not include mental health professionals (

38), understanding factors that facilitate or hinder access to these professionals is critical, particularly for low-income patients.

This study had a number of limitations. The data for this study—national Medicaid claims and enrollment files—do not include information on stage at diagnosis. Receipt of consultations or mental health services was determined with CPT codes present in Medicaid claims. Although Medicaid claims including CPT codes can be submitted by providers other than physicians (depending on state regulations and Medicaid policies), it is likely that receipt of care from other mental health care providers, including psychologists, social workers, and advanced-practice psychiatric nurses, was not fully captured in this study. Research using other data sources is needed to collect more complete information on factors influencing receipt of mental health services among Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer.

The data are from 2006–2008, which may limit relevance to current policies. In particular, these data do not capture the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on Medicaid. However, reimbursements for many medical care services other than primary care visits have experienced little change over the past decade. In addition, to include information on reimbursement, only those enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid were included. No information is available in the MAX data on patient-reported outcomes (for example, satisfaction and quality of life) or clinical measures. We were also unable to determine whether individuals who had mental health diagnostic or treatment encounters actually had mental health conditions. Finally, the dependent variable (receipt of mental health services) captured service use only, but it did not provide information on quality of care.