The World Health Organization (WHO) issued a call to action to improve treatment adherence, stating that “poor adherence to treatment of chronic disease is a worldwide problem of striking magnitude” (

1). In the mental health field, effective psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for serious mental illness underpin the importance of ongoing treatment engagement. The therapeutic benefit of mental health services and pharmacotherapies depends on clients accessing and engaging in treatment. Unfortunately, approximately 15%−32% of clients receiving outpatient mental health care end treatment prematurely (

2,

3). Nonattendance at psychiatric appointments and low frequency of mental health visits have been associated with poor outcomes, including increased hospitalization (

4–

6). Similarly, nonadherence to psychotropic medications limits the effectiveness of pharmacological management across a number of mental health conditions (

7–

9). For individuals with schizophrenia, in which long-term antipsychotic maintenance is recommended (

10), low adherence has been associated with poor prognosis, hospitalization, and suicide (

8,

11,

12). According to the WHO, adherence may be attributable to multiple factors, including treatment environments that take the client’s values and preferences into account (

1).

Shared decision making has been identified as a promising approach for encouraging treatment engagement among individuals with serious mental illness (

3,

5,

13–

15). Shared decision making is a model of patient-provider communication designed to marry the evidence on treatment options with the values and preferences of clients and families. Although varying definitions have emerged, the most commonly cited criteria require the active participation of the individual and the clinician in information sharing, leading to a treatment decision made and agreed upon by both parties (

16). Historically, shared decision making was promoted on ethical grounds. The 1982 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine called for medical professionals to engage in “shared decision-making based on mutual respect and participation” (

17). Although ethical considerations are sufficient, the promise of shared decision making is that it will also lead to ongoing engagement in treatment and thereby improve clinical outcomes (

5,

15).

Recent systematic reviews indicate that little is known about the impact of shared decision making on sustained engagement in mental health services—for example, missed appointments or dropout rates—and studies examining the impact of shared decision making on psychotropic medication adherence have had mixed results (

18–

22). A pilot study of treatment continuation found that veterans randomly assigned to receive a 30-minute shared decision-making session prior to initiating therapy were more likely to complete a course of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (

23). Similarly, a randomized controlled study of depression in primary care found that shared decision making increased adherence to the treatment plan among individuals receiving medication management (

22,

24,

25). However, three investigations of psychotropic adherence have not found a relationship between shared decision making and adherence (

26–

29).

Two large, well-controlled studies that included shared decision making as one component of a multifaceted intervention reported successful gains in treatment continuation and psychotropic medication adherence (

30,

31). The Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Connection Program has been associated with longer retention in treatment and increased antipsychotic medication adherence (

31). A primary care–based depression prevention trial that used shared decision making and other interventions yielded increased adherence to antidepressant medication (

30). However, the contribution of shared decision making relative to that of other components of these multifaceted interventions was unclear. More studies are needed to understand the relationship between shared decision making and ongoing mental health treatment engagement.

CommonGround is one of the most widely implemented shared decision-making programs in mental health settings (

13,

32–

38). Developed by Pat Deegan & Associates, this Web-based tool guides clients through a questionnaire that results in a shared decision-making report summarizing the individual’s treatment concerns, goals, wellness strategies, and outcomes, which creates a foundation for shared decision-making discussions between the individual and his or her physician (

32). To date, no studies have examined the impact of CommonGround on ongoing engagement in mental health services, and only one study has looked at medication adherence. Stein and colleagues (

29) examined psychotropic medication adherence in the six months after initial use of CommonGround and did not find any impact.

In this study, we examined the impact of the use of CommonGround on ongoing outpatient mental health treatment engagement. Medicaid-enrolled users in 12 clinics were compared with a propensity score–matched control group to examine continuing engagement in outpatient services in the year following first use of the CommonGround shared decision-making program. In addition, for the subset of individuals with schizophrenia, for which long-term management with antipsychotic medication is recommended, we examined the relationship between shared decision making and antipsychotic medication adherence.

Methods

Web-Based Shared Decision-Making Tool

My Collaborative Health Outcomes Information System (MyCHOIS) is the client-facing component of the Psychiatric Services and Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System (PSYCKES), a Web-based platform for supporting clinical decision making and quality improvement developed by the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) (

39). CommonGround, developed by Pat Deegan & Associates, is one tool among several instruments available to clients in MyCHOIS. In this report, “MyCHOIS–CommonGround users” refers to clients who used MyCHOIS to complete a CommonGround shared decision-making report.

CommonGround shared decision-making reports are completed by clients prior to their medication appointments. The reports summarize their perspective on symptoms, functioning, treatment progress, and concerns. Peer staff assist clients as needed in using the CommonGround program, including creating accounts, logging in, entering data, and printing and reviewing shared decision-making reports (

32,

40). During the appointment, the client and practitioner review the report and work together to develop a shared decision.

MyCHOIS–CommonGround was implemented in 12 Medicaid mental health outpatient clinics in New York State (go-live dates ranged from February 2011 to March 2014).

Data Sources

MyCHOIS–CommonGround user logs were extracted to identify users and dates of use. Client demographic characteristics, diagnoses, Medicaid eligibility, inpatient and outpatient mental health service use, and prescriptions were extracted from the New York State OMH Medicaid data warehouse. The study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the New York State OMH Institutional Review Board.

Study Sample

MyCHOIS–CommonGround user group.

All Medicaid-enrolled adults served at one of the 12 MyCHOIS–CommonGround clinics between February 1, 2011 (go-live month for the first clinic that implemented MyCHOIS–CommonGround), to March 1, 2014 (N=2,632), who completed a shared decision-making report during that period (N=1,100) were included in the initial sample. For each user, the first completed report was the index date. Individuals with incomplete Medicaid data were excluded from the sample, including those without continuous Medicaid eligibility for the year before and after their index date (N=212), those with dual Medicare coverage (N=389), and those with no psychiatric diagnosis (N=27). The final sample consisted of 472 MyCHOIS–CommonGround users. [A flow diagram in an online supplement shows the recruitment process.] The sample members were of low socioeconomic status because of Medicaid inclusion criteria.

Control group.

A simple random sample (N=220,000) of adult Medicaid enrollees receiving a mental health clinic service between February 1, 2011, and March 1, 2014 (excluding those served at MyCHOIS clinics) was extracted from the OMH Medicaid database. After excluding individuals with incomplete Medicaid data (that is, those also covered by Medicare and those without continuous Medicaid enrollment in the year before and after the index date), a 2:1 propensity score–match algorithm (

41,

42) was used to construct a control group (N=944) matched with MyCHOIS–CommonGround users on baseline characteristics, including demographic characteristics (age, gender, race-ethnicity, and geographic region); index date; clinical characteristics (primary psychiatric diagnosis and any substance use disorder diagnosis); and mental health service use in the year prior to the index date, including mental health treatment engagement (number of months with any outpatient specialty mental health service), use of psychiatric rehabilitation services, and psychiatric inpatient hospitalization (community hospital and state psychiatric center). For all MyCHOIS–CommonGround users, the propensity score–match algorithm identified two individuals with the closest propensity score (log-odds score) on the basis of all baseline characteristics. The propensity score match used a “greedy” algorithm that looked for the best and second-best match by using the nearest-available-neighbor method (

41).

Definitions and Measures

Index date was defined as the date of the first completed shared decision-making report for the CommonGround users group. For the control group, the index date was the date of a mental health clinic service and was determined as part of the propensity score match to ensure that the control and CommonGround groups had similar index dates. The baseline time period was one year (365 days) prior to the index date. The follow-up time period was the year following the index date. Age was determined as of the index date. Region (based on the client’s address) was categorized as New York City, western New York, central New York, and other. Primary diagnosis was determined by the preponderance method (

43). Clients were assigned the most frequent primary diagnosis associated with the ten services most proximal to their index date. In the event of a tie, clients were assigned the diagnosis associated with the highest level of service.

Ongoing engagement in outpatient specialty mental health service was adapted from methods used by Dixon and colleagues (

44), by using months with a mental health service as a measure of continued treatment engagement. We calculated the number of months during the year of observation in which the client received one or more routine (nonemergency) specialty mental health outpatient services from any Medicaid provider in New York State, including mental health clinic, outpatient psychiatric rehabilitation, and assertive community treatment. Outpatient crisis or emergency services were excluded.

The proportion of days covered (PDC) with antipsychotic medications among individuals with schizophrenia (

ICD-9 codes 295–295.99) was used to examine medication adherence in the year prior to and the year following the index date (

45). We restricted the examination of medication adherence to antipsychotic medications for individuals with schizophrenia because it was the largest diagnostic category in the cohort and because long-term or lifelong use of antipsychotic medications is the cornerstone of pharmacological management (

10). Using an approach adapted from Nau (

45), PDC was calculated as the total number of days that antipsychotic medication was available to the individual (the number of days’ supply of prescriptions filled) divided by the total number of days in the community (365 minus any days hospitalized) during the year of observation. For two prescriptions filled on the same day, the prescription with the greater days’ supply was used. For prescriptions filled on different days, overlapping days were summed.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests (for categorical variables), and t tests (for continuous variables) were used to characterize cohorts and to test for differences between the MyCHOIS–CommonGround and control groups at baseline. Multilevel linear models were used to examine interactions between groups over time and to account for lack of independence between baseline and follow-up assessments (same individuals assessed at two time periods). Specifically, PROC MIXED models examined the association between MyCHOIS–CommonGround use and time period (baseline [0] to follow-up [1]) on ongoing outpatient treatment engagement and antipsychotic medication adherence. Any observed statistical differences between groups at baseline were adjusted for in the model. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4.

Results

No significant differences were found between the MyCHOIS–CommonGround group and the propensity score–matched control group on any baseline variables (

Table 1). Schizophrenia was the most prevalent diagnosis (40%), and approximately a third had a primary or comorbid substance use disorder. Approximately 15% had a psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year. For the subcohort with schizophrenia (results not shown), no significant differences were found between groups on any baseline characteristics, with the exception of region (for the New York City region, 65% MyCHOIS versus 70% control group, p=.01).

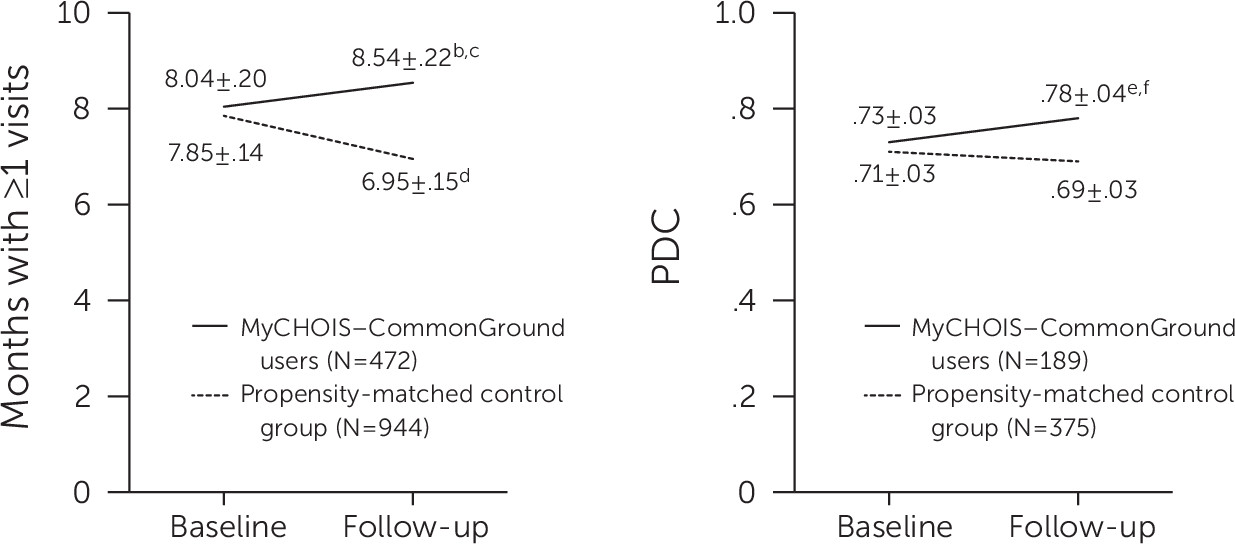

Figure 1 presents the least-squares means and standard errors from the multilevel model for engagement in services and antipsychotic adherence at baseline and follow-up for the MyCHOIS–CommonGround and control groups. At baseline, no between-group differences were noted in engagement in outpatient mental health services. Similarly, for the subset of individuals with schizophrenia, no between-group differences in antipsychotic medication adherence were noted. However, during the follow-up year, the MyCHOIS–CommonGround users had a higher level of ongoing engagement in outpatient mental health service compared with the control group (months with use of a service, 8.54 versus 6.95; p<.001). At one-year follow-up, within-group comparisons indicated a significant increase in ongoing engagement for the MyCHOIS–CommonGround users group and a significant decrease in engagement for the control group. Similarly, for the subset of users with schizophrenia, no differences in antipsychotic medication adherence were found between the groups at baseline, but the MyCHOIS–CommonGround group was significantly more adherent during the follow-up year compared with the control group (PDC, .78 versus .69; p=.01). Within-group comparisons indicated a significant increase in antipsychotic adherence for the MyCHOIS–CommonGround group, whereas no change was noted for the control group.

Table 2 presents results of the multilevel linear models estimating the association between MyCHOIS–CommonGround use and ongoing engagement in specialty mental health services and—for the subset of individuals with schizophrenia—the PDC by one or more antipsychotic medications. Consistent with findings shown in

Figure 1, multilevel linear models identified statistically significant interactions between groups over time for both ongoing outpatient mental health treatment engagement (β=1.40, p<.001) and antipsychotic adherence (β=.06, p<.01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report an association between shared decision making and ongoing service engagement or medication adherence for individuals with serious mental illness. This propensity score–matched intervention study found that individuals who used MyCHOIS–CommonGround, a peer-supported and Web-based shared decision-making program, were significantly more engaged in outpatient mental health services during the following year, compared with a control group (that is, they used a mental health outpatient service 1.6 more months per year). In addition, the subgroup of MyCHOIS–CommonGround users with schizophrenia had significantly higher antipsychotic medication adherence during the follow-up year (9% more days with medication). These findings contribute to our nascent understanding of the impact of shared decision making in mental health—and specifically of the impact of the CommonGround program.

This study builds on previous evaluations of the impact of shared decision making in health services and lends support to the idea that shared decision making can improve outcomes through increased patient engagement in ongoing treatment. A randomized controlled study in primary care in Germany found that shared decision making increased adherence to depression treatment (

22,

24,

25). Investigation of the causal relationships between shared decision making and depression outcomes in primary care indicated that client participation in treatment decisions improved clinical outcomes through increased treatment adherence.

This study supports these findings and extends them to ongoing engagement in specialty mental health services among individuals with serious mental illness and builds on previous evaluations of the impact of CommonGround. Two groups of investigators found that CommonGround use was associated with improvement in client-reported outcomes, including psychiatric symptoms, health functioning, and recovery progress (

46,

47). The study reported here suggests that these improved outcomes among CommonGround users may have been due in part to increased treatment engagement.

It is important to establish the benefit of shared decision making beyond the ethical considerations upon which it was founded, in part to inform implementation decisions (

17). Implementation of shared decision-making programs, such as CommonGround, can be challenging and requires leadership and staff commitment and upfront and ongoing resources (

48,

49). However, payers, with rare exception, have not reimbursed mental health service providers for shared decision-making programs (

34). In previous work, we found that lack of reimbursement for CommonGround served as a significant barrier to adoption and sustainment of the program. Programs such as CommonGround that require dedicated peer support staff and equipment would benefit from additional evidence of impact, including the relationship between program fidelity and impact, as well as economic evaluations to inform implementation decisions by payers, policy makers, and providers (

50).

In contrast to the dearth of studies on engagement and shared decision making, four prior studies have examined shared decision making and psychotropic medication adherence; however, most did not find a significant relationship (

26–

29). In this study, we focused specifically on antipsychotic adherence in schizophrenia, where the ongoing use of an antipsychotic is clinically indicated (

10,

51) and where antipsychotic adherence, rather than psychotropic use in general, is associated with improved outcomes (

52). This study also benefited from a large intervention sample from 12 sites, use of a propensity score–matched control group selected from a random statewide sample, and a 12-month period of observation during which there was an ongoing opportunity to participate in shared decision making. However, given mixed results in the literature and the limitations of this study, further research is warranted.

This study had several limitations. First, propensity-score matching controls for a large number of baseline characteristics; however, it cannot control for unmeasured attributes that may be confounders. Second, our measures of medication adherence, shared decision making, and ongoing engagement in treatment were objective but indirect. Medicaid prescription fills were used to assess antipsychotic medication adherence, but it was unknown whether the client took the medication as prescribed or received medications that were paid for out of pocket or through other non-Medicaid sources. MyCHOIS–CommonGround user logs were used to assess whether a shared decision-making report was completed, but the quality of the encounter between the client and the prescriber was not examined. Similarly, ongoing engagement in specialty mental health care was assessed by using Medicaid administrative data, and information pertaining to missed appointments or appropriate termination of treatment was lacking. Third, ongoing contact with a service provider is only one component of engagement in treatment services, and impacts of CommonGround on other important aspects of engagement, including completion of a course of treatment (

23), adherence to the treatment plan (

24,

25), and patient activation and related constructs, are areas for future study (

53). In addition, potential impact of the program on nonusers—for example, as a result of changes in staff approach—was not examined. Finally, findings may not be generalizable to other populations or settings. For example, this study examined Medicaid-enrolled individuals who were not dually eligible for Medicare and who were receiving services in mental health clinics. Future study is needed to examine the impact of CommonGround on engagement among individuals with poor service engagement, in other treatment settings, and with other insurance types.

Conclusions

This study, the first to examine the impact of shared decision making on ongoing engagement in mental health treatment among individuals with serious mental illness, found a modest but significant improvement in outpatient treatment engagement and, for the subset of individuals with schizophrenia, an increase in antipsychotic adherence. Shared decision making is a promising approach to enhancing patient-centered care, improving the use of services, and ultimately improving outcomes of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elizabeth Austin, M.A., for managing initial implementation of MyCHOIS–CommonGround and Jeremy Herring, M.A., for implementation and application support.