Homelessness is a pressing social and economic issue. Many people experiencing homelessness also experience mental illness (

1), and rates of health and social service use among homeless people are high compared with those of the general population (

2,

3).

Previous studies investigating homeless individuals’ service use have predominantly relied on cross-sectional data or time-averaged values (

4–

7). Time-patterned approaches can yield further insights because they also consider the timing of events (

8). Latent class growth analysis (LCGA) is used to model longitudinal changes in outcome by identifying unique and relatively homogeneous subpopulations of individuals within a larger heterogeneous sample (

9,

10). Latent growth modeling techniques have been applied in various areas of health and social science research (

11–

13) and, in particular, to model trajectories of housing stability and associated predictors (

14–

16). However, to our knowledge only one study has assessed service utilization trajectories among homeless people as an outcome by using latent growth modeling (

17). As researchers have turned to computer modeling to explore the complex dynamics of homelessness (

18), it is of interest, for modeling and service planning purposes, to identify trajectories of shelter utilization and characteristics of individuals most at risk of continued or increased shelter use. In many service systems, the number of individuals in emergency shelters constitutes a substantial portion of the total number of homeless individuals on any given night because shelters often serve as their first point of contact with the system. Furthermore, the number of individuals in emergency shelters is relatively easy to track. Shelter use is thus of particular interest to decision makers.

Unlike traditional homelessness interventions that require participants to abstain from drug use, remain sober, or meet other conditions, Housing First offers permanent housing to participants immediately (

19). This study identifies trajectories of shelter use among homeless individuals and baseline variables associated with different trajectories. It also assesses whether recipients of Housing First experience different trajectories of shelter use compared with recipients of care as usual.

Methods

This is an exploratory secondary analysis of data collected during the At Home/Chez Soi trial, which tested Housing First interventions for homeless people with mental illness in five Canadian cities: Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, and Moncton. The study protocol and results have been published elsewhere (

20–

22). The At Home/Chez Soi study was registered with the International Standard Randomized Control Trial Number Register (42520374). It was approved by the research ethics boards of all participating institutions (

20–

22).

The At Home/Chez Soi Study

Participants were recruited through referrals from a variety of health and social service agencies serving homeless people as well as through street outreach. Eligible individuals were legal adults in their respective provinces, were homeless or precariously housed, and had at least one of six mental disorders (psychotic disorder, major depression, etc.) as indicated by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (

23). Individuals who were already receiving services from an assertive community treatment (ACT) or an intensive case management team were excluded because of the services’ similarity with the Housing First intervention.

Participants were classified as high need or moderate need prior to random assignment (

21). Individuals categorized as high need had a current diagnosis of bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder as indicated by the MINI and a score of less than 62 on the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (

24,

25). They also met at least one of the following criteria: were hospitalized twice in any 1-year period within the past 5 years, experienced substance abuse or dependence as indicated by the MINI or a referral source, or had been arrested or incarcerated within the past 6 months (

20). All other participants were classified as moderate need. An adaptive randomization algorithm was used (

26). Participants were enrolled from October 2009 to July 2011. Because of the nature of the intervention and measures used, neither participants nor interviewers were blinded.

The intervention for all participants in the treatment condition, Housing First, was based on a recovery-oriented, harm-reduction model with no prior requirements for housing readiness (e.g., sobriety). High-need participants were randomly assigned into either Housing First with ACT or into treatment as usual, and moderate-need participants were randomly assigned into Housing First with intensive case management or into treatment as usual. Because of the small sample size in Moncton, participants were not stratified based on need, and all individuals were randomly assigned into Housing First and ACT or into treatment as usual. Following the approach of the Pathways to Housing program (

19), both high-need and moderate-need participants randomly assigned into Housing First were offered a choice among scattered-site apartments along with a rent subsidy and the support of a housing team that worked with landlords (

21). Two fidelity assessments of various domains of the intervention were conducted across all sites, with high ratings received on both evaluations (

27). Individuals receiving treatment as usual had access to all the typical services available in their city. Participants were followed for up to 2 years.

Measures

The primary outcome of interest was use of emergency homeless shelters, characterized by total days of stay during a 1-month period. The Residential Time-Line Follow-Back calendar, which has high test-retest reliability and concurrent validity (

28), was administered every 3 months starting at baseline to record the housing histories of participants.

The following baseline variables for this analysis were ascertained through self-report: age at enrollment, gender, race-ethnicity, level of education, baseline monthly income, alcohol abuse or dependence, drug abuse or dependence, psychiatric hospitalization history (having been hospitalized for a mental illness at any time for longer than 6 months or more than once within a year in the past 5 years), history of criminal justice involvement (having been arrested at least twice, imprisoned at least once, or having served probation or other community sanction), experience of inadequate health care access in the past 6 months, total time homeless, and suicide risk (no/low, moderate/high).

Childhood trauma was identified with the Adverse Childhood Experience questionnaire, which asks questions related to events experienced in the first 18 years of life. A total score was calculated based on various experiences of childhood abuse and household dysfunction (

29). Functioning was assessed with the MCAS, an instrument developed for individuals with chronic mental illness (

24,

25). The MCAS consists of 17 items that assess functioning in several aspects of life, including general medical health, intellectual functioning, and social effectiveness. Baseline psychiatric diagnosis was evaluated using the MINI, a short structured interview developed for diagnosing psychiatric disorders (

23), and was recoded into a binary variable indicating a mental disorder with or without psychosis. Family social support was measured with the 20-item Quality of Life Index (QOLI-20) family subscale score. The QOLI-20 is a structured self-report interview that uses a 7-point scale to capture general life satisfaction and specific domains of life satisfaction, such as living situation, family relations, social relations, finances, and health (

30). Number of comorbid conditions was included as an indicator of general medical health status and was measured using the Comorbid Conditions List, a comprehensive list of general medical health disorders developed for the original study (

31).

Statistical Analysis

Because fewer than 10% (N=197) of the participants were missing outcome data, only participants with complete observations for the outcome were included in this analysis. A sample of 2,058 individuals was analyzed (1,133 participants in treatment and 925 in control) from the 2,255 total participants in the original study.

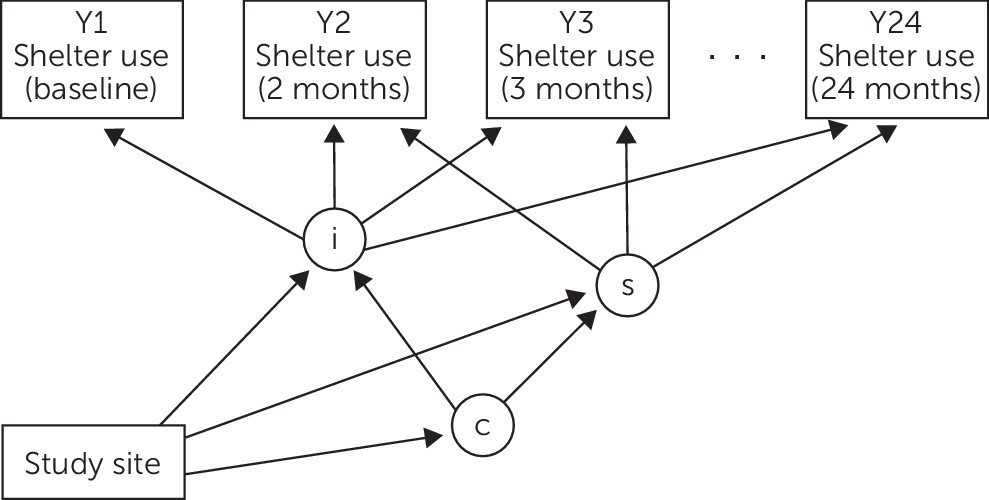

LCGA was used to model unique classes of shelter use trajectories (

Figure 1). Once trajectories were established and individuals were grouped into their respective classes, multinomial regression was performed to assess whether baseline covariates could predict class membership (

17).

Models considered for the outcome trajectory analysis included linear, quadratic, cubic, and piecewise growth curves over 24 time points for between two and six latent classes. The best model was then selected based on the Schwarz-Bayesian information criterion (

32), and results were further validated using estimated entropy values (

33) and substantive interpretation of estimated class trajectories. Because the outcome variable had a preponderance of zeros, a small constant of 0.01 days of use was added to all observations to prevent inaccuracies in trajectory estimation due to the floor effect. The outcomes were log-transformed to ensure the modeling respected the boundaries of the data and generated estimations only in the positive range when back-transformed onto the original scale.

Multiple imputation was conducted for all predictor variables with missing data by using a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach. The imputation procedure utilized the variance-covariance method under the unrestricted H1 model (

34). Data for independent variables were imputed for approximately 0% to 13% of the total observations, with subsequent analyses performed across 20 imputed data sets.

Treatment and control groups were combined and analyzed together to allow for clear identification of classes that were common to both groups. Treatment group was, however, included in the regression model as a covariate. Site was included as a covariate to adjust for clustering. All analyses were performed with Mplus, version 8.

Results

Demographic and other variables were similar in the analyzed and original samples. (A table comparing participant characteristics in the analyzed versus the original sample is available in an online supplement.) The sample in the original study had a mean±SD age of 40.9±11.2 years. Approximately 69% (N=1,545) of the sample were male (females were oversampled to ensure adequate numbers for analysis). Twenty-one percent (N=474) were indigenous, and 70% (N=1,579) were single or never married. Forty-one percent (N=925) were classified as high need. Fifty-five percent (N=1,241) did not graduate from high school, and 92% (N=2,075) were unemployed at baseline. The average lifetime duration of homelessness was 75.2±138.2 months. Thirty-six percent (N=812) of the sample were identified as being at moderate or high risk for suicide at baseline. Thirty-four percent (N=767) were diagnosed as having a psychotic disorder, and 67% (N=1,511) experienced substance abuse or dependence.

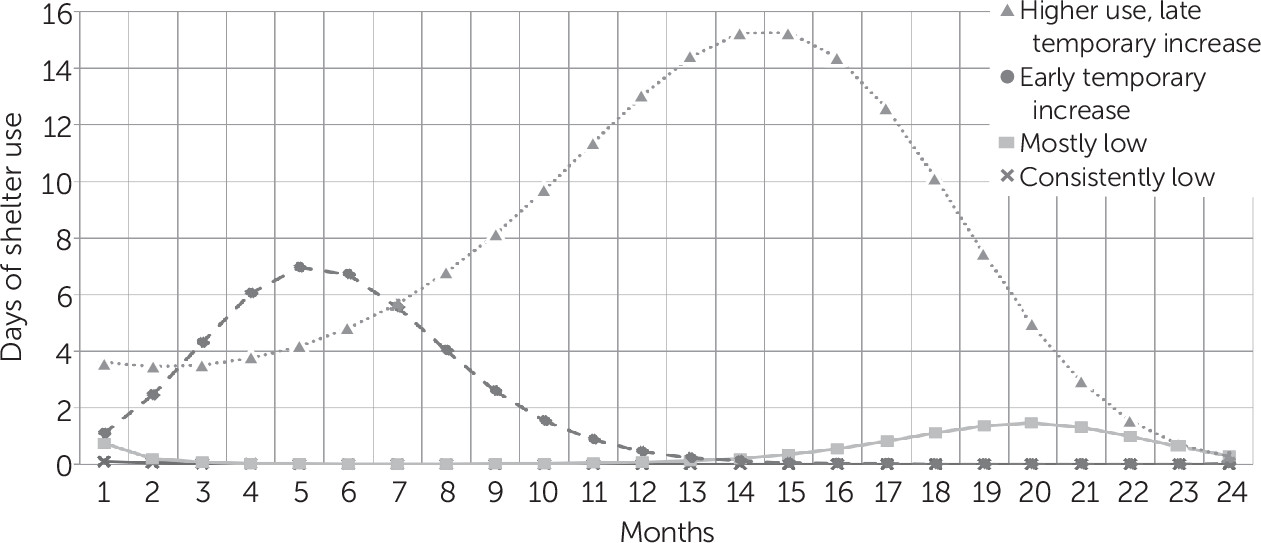

The selected model was the four-class cubic model (

Figure 2). The log-transformed outcome was then back-transformed onto the original scale for ease of interpretability. Potential predictors of class membership and their distributions are outlined in

Table 1.

Class 1, the group with consistently low shelter use, was the largest class (79%, N=1,631). This class demonstrated nearly 0 days of shelter use throughout the study. Class 2 (mostly low) was the smallest class (6%, N=120). This class included participants who had slightly higher baseline shelter use than class 1 and then exhibited a small temporary increase toward the end of the follow-up period, after about a year of nearly zero use. Class 3 (early temporary increase) (9%, N=179) consisted of individuals whose number of days in shelter increased initially but declined to almost 0 days at month 14 and remained low until the end of the study. Class 4 (higher use, late temporary increase) (6%, N=128), had the highest shelter use of all four classes. This group was composed of participants who had higher shelter use initially and then experienced a notable increase in use, which peaked at month 15 before declining to almost 0 days at the end of 24 months. The number of days of shelter use per month was as much as 15 days higher in class 4 than in class 1 over 24 months.

Table 2 shows the results of the multinomial regression. Compared with class 1, members of classes 2, 3, and 4 all had lower odds of being enrolled in Housing First (class 2: odds ratio [OR]=0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.34–0.72; class 3: OR=0.21, 95% CI=0.15–0.31; class 4: OR=0.14, 95% CI=0.09–0.22), suggesting that enrolment in Housing First is protective against higher shelter use, whether that higher use occurs early or later. More than three-fifths (62%, N=1,009) of members of class 1 had been assigned to the intervention group.

Compared with class 1, members of class 2 were significantly less likely to be female (OR=0.57, 95% CI=0.35–0.92) but more likely to have a higher income (OR=1.22, 95% CI=1.01–1.46) or drug abuse or dependence (OR=1.65, 95% CI=1.04–2.62). Members of class 3 were more likely to be older (OR=1.03, 95% CI=1.01–1.04). Participants in class 4 were less likely to experience alcohol abuse or dependence (OR=0.47, 95% CI=0.30–0.72) or to be at moderate/high risk of suicide (OR=0.54, 95% CI=0.34–0.88) but were marginally more likely to have been homeless for longer at baseline (OR=1.03, 95% CI=1.01–1.06).

Discussion

LCGA identified four distinct trajectories of shelter utilization over the course of the trial. The number of shelter days declined to low values by the end of the study for all classes, suggesting that participants generally achieved positive outcomes at the study’s end. The uniformly low level of shelter use by the end of the study can likely be attributed to the intervention for the participants assigned to that group, whereas usual services may have simply taken a longer time to achieve the same result for participants receiving care as usual. A significant fraction of participants did not have a long history of continuous homelessness, and usual services may have been instrumental in helping many return to housing.

Participants in the three classes associated with greater shelter use were also all less likely to be in the intervention group. The effect of Housing First on utilization trajectories is further supported by the magnitudes of the odds ratios. Participants assigned to Housing First had the lowest odds of following the worst outcome trajectories (higher use, late temporary increase), with the odds of class membership increasing with decreasing overall shelter use. These findings are consistent with prior evidence that Housing First is associated with reduced overall shelter use (

20,

22,

35).

Results indicate that, in general, the two classes with the most shelter use were more likely to include older individuals and those with a longer time homeless at baseline and less likely to include individuals with alcohol abuse or dependence or moderate/high suicide risk. The mostly low use class (class 2) had a marginally worse outcome than class 1 and was more likely to consist of males, individuals with drug abuse or dependence, and individuals with higher income. The association of alcohol use with lower shelter use, which at first glance may appear counterintuitive, may have been due to the restrictions that many shelters impose on alcohol or drug consumption. Although the effect of site was not of primary interest, individuals with trajectories of greater shelter use (classes 3 and 4) were more likely to be living in a city with a larger population, such as Toronto, compared with Winnipeg or Moncton. This finding may be an indication that individuals experiencing homelessness gravitate toward larger cities or a reflection of higher living costs or availability of shelter beds in larger cities. We were unable to discriminate among these hypotheses with the available data.

Similar to the findings of Gleason et al. (

17), we found four classes of shelter use, with a similar reference class (mostly low use) consisting of over 75% of the sample. Our higher use, late temporary increase class (class 4) is arguably comparable with one of the classes identified in that paper as well; both demonstrate high emergency shelter utilization for a relatively long time, characteristic of chronic shelter users. However, the two intermediate classes in Gleason et al.’s analysis showed much higher shelter use than the intermediate usage classes in this study. Direct comparisons are difficult, however, because Gleason et al. modeled trajectories of not only shelters but also outreach services, and none of their participants were provided an intervention such as Housing First, which reduced shelter usage among about half of our study’s participants.

Previous At Home/Chez Soi findings reported significant improvements in residential stability for Housing First participants compared with participants receiving treatment as usual (

20,

22). Adair et al. (

16) also reported that Housing First participants tended to follow more favorable trajectories in terms of stable housing than did control participants. Consistent with these findings, the results presented here reflect lower shelter utilization among Housing First participants compared with individuals accessing usual services only.

This study had several strengths, including a large sample, low attrition, well-implemented Housing First programs, and a large, multisite sample enabling complex analyses such as LCGA to be performed. Days of shelter utilization were ascertained using a Time-Line Follow-Back method, allowing for more precise trajectories to be modeled. Although several variables were ascertained through self-report, the validity of self-reported data has been confirmed by various studies (

36,

37). Some limitations also need to be noted. Not all potentially important predictors could be evaluated, including those that exert more systemic effects, such as social acceptance and marginalization (

17). Certain factors, such as childhood trauma, may be more complex than what the indicators could capture. Because of the two-step methodology of modeling trajectories and then assessing the associations of baseline predictors with these trajectories, any statistical uncertainty in class assignments was not reflected in the results of the regression analyses.

Conclusions

This analysis explored trajectory classes of shelter utilization and associated predictors in a multisite Canadian randomized controlled trial of Housing First. Because many factors can lead to homelessness, homeless individuals often have diverse backgrounds and characteristics. Results from this study indicate heterogeneity in the observed patterns of shelter use and some associations between sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and homelessness history and the likelihood of following different shelter use trajectories. Heterogeneous responses to the intervention, reflected in the fact that intervention participants may be found in all four classes, highlight the importance of addressing the inherent diversity in the homeless population by identifying individuals with the greatest needs and allocating sufficient resources to treating them.

By identifying the characteristics of subgroups susceptible to different trajectories of shelter use, this study presented a different way of characterizing individuals for whom Housing First is effective. Results can inform simulation models designed to predict the effects of interventions such as Housing First on homelessness and resource use trajectories for different subgroups. Further research is needed on whether individuals predicted to belong to classes of higher shelter use (especially higher use, late temporary increase) would benefit from additional interventions. Evaluating the effects of time-varying predictors, such as changes in substance dependence, is also of interest because these variables may influence service use patterns over time.

Future studies should examine trajectories of other important services used by homeless individuals, such as incarcerations or emergency department visits, to gain further insight into the patterns that homeless individuals follow as they move through the service system. Longitudinal trajectory modeling could also be applied to other outcomes, such as quality of life or community integration.