Major depressive disorder is a significant public health concern in the United States, with a lifetime prevalence estimated at 19.2% and a 1-year prevalence of 7.1% (

1,

2). Treatment-resistant depression refers to major depressive disorder that fails to respond to adequate treatment. Depending on the definition, treatment-resistant depression affects an estimated 20%−30% of patients with major depressive disorder (

3). Patients with treatment-resistant depression have higher symptom severity, longer episodes of depression, diminished quality of life, and an increased suicide risk, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression (

3–

6). These data suggest the potential benefits that timely and effective antidepressant treatment can have for patients with major depressive disorder. However, individuals with treatment-resistant depression currently have limited proven treatment options (

7,

8).

Previous research that examined the burden of treatment-resistant depression among commercially insured and Medicaid populations found significantly higher health care resource utilization and costs among patients with treatment-resistant depression, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression and patients without major depressive disorder (

5,

9–

13). One study, which used 2001–2009 data and included Medicaid, Medicare, and commercially insured populations, found that treatment-resistant depression was associated with 29.3% higher health care costs (

14). However, this study defined treatment-resistant depression at a higher threshold of treatment failure, which may have resulted in underestimation of total health care burden.

Given the heterogeneity in operationally defining treatment-resistant depression, it is challenging to compare between studies the extent to which patterns in treatment-resistant depression burden are analogous across payers. This study aimed to explore these intricacies by applying a standardized definition of treatment-resistant depression across patients with major depressive disorder among the following payer populations: commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare. This study assessed the incremental treatment burden of treatment-resistant depression among patients with major depressive disorder by comparing health care resource utilization and associated costs across patients with treatment-resistant depression versus patients with treatment-responsive depression covered by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare supplemental health plans. In addition, this study sought to understand health care cost trends over time associated with health care resource utilization by treatment-resistant depression status.

Methods

Data Source

This retrospective observational study used administrative claims data from three Truven MarketScan databases (commercial, Medicare supplemental, and Medicaid databases) to capture person-specific health care utilization and associated expenditures from January 2006 (for commercial and Medicare supplemental) or January 2007 (for Medicaid) through October 2017. The commercial database includes employees and their family members in the United States covered by private health insurance provided by approximately 100 large employers. The Medicaid database includes over 44 million Medicaid enrollees from multiple states. The Medicare supplemental database includes retired beneficiaries with supplemental health care insurance covered by employers and includes records of all services paid by Medicare, private insurance, and beneficiaries as out-of-pocket costs (

15). Each database contains information on eligibility, demographic characteristics, inpatient and outpatient medical claims, outpatient prescription claims, and costs associated with adjudicated claims. Institutional review board approval was not sought for this study because all data had been previously collected and deidentified.

Study Population

The study included adults ages 18 and older with a major depressive disorder diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2x, 296.3x; ICD-10-CM codes F32.x, F33.x) who had received an antidepressant treatment anytime between April 1, 2006, and October 31, 2016. In addition, patients were required to have continuous enrollment in their benefit plans during the 6 months preindex and 12 months postindex date, where index date was defined as the date on which they received their initial antidepressant treatment. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, dementia, or other psychosis. (A CONSORT diagram of sample composition is available in an online supplement to this article.)

Patients were further stratified into those with treatment-resistant and treatment-responsive depression based on their treatment patterns. Treatment-resistant depression was defined as failure of at least two antidepressant treatment courses of adequate dose and duration within a depressive episode among patients with a major depressive disorder. Adequate dose was defined as the minimum starting dose recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (

16). Adequate duration was defined as at least 6 weeks of continuous therapy with no gaps in medication possession longer than 14 days. Failure of a treatment course was defined as an antidepressant molecule switch within or outside of the treatment class within 90 days after the end of the previous treatment, the addition of a new antidepressant, or the initiation of an augmentation therapy. The date of initiation of the third antidepressant or augmentation medication following the failure of two treatments at adequate dose and duration was used as the date of treatment-resistant depression diagnosis. Patients with treatment-responsive depression were identified from the subset of patients who were not identified as having treatment-resistant depression. Because of the large size of the treatment-responsive populations, 15% of these patients were randomly selected for inclusion in this study to mitigate the risk of overpowering the study (see

online supplement for a table listing inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Outcome Measures

Outcomes included all-cause and mental health–related health care utilization (i.e., outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and emergency department [ED] visits) and health care costs over the 12-month postindex follow-up period. Health care costs were adjusted to 2018 dollar values by using the medical care component from the Consumer Price Index (

17).

Only a few patients across the three payer populations reported having any hospitalizations or ED visits at any point during the follow-up period. Hence, these outcomes were collapsed to binary variables representing any hospitalization or ED visit versus no hospitalization or ED visit, respectively.

We captured all health care utilization and costs incurred during the 12-month postindex follow-up period to create all-cause outcome measures. Mental health–related health care utilization and cost measures included medical and pharmacy claims with ICD-9-CM codes 290–319 or ICD-10-CM codes F01–F99.

Analytic Approach

Descriptive analyses summarized patient demographic characteristics and baseline clinical characteristics (measured during the 6-month preindex period) by treatment-resistant depression status. Differences in baseline characteristics across patients with treatment-resistant and treatment-responsive depression were assessed by a regression of each characteristic, with treatment-resistant depression as the dependent variable. Separate regression analyses were carried out for each outcome of interest for each separate payer population (commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid). Logistic regressions were performed to model the association between treatment-resistant depression status and the dichotomous outcome measures (i.e., hospitalizations and ED visits). Negative binomial regressions were performed to determine the association between treatment-resistant depression status and outpatient visits. For total costs over the follow-up period, linear regression models were used to assess the relationship with treatment-resistant depression status.

All regression analyses were adjusted for the following relevant covariates: age, gender, insurance plan type, baseline Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, and baseline all-cause health care costs. Information on race-ethnicity was available only for the Medicaid sample, whereas information on region was available only for the commercial and Medicare data sets. Hence, these variables were included in the analysis of the corresponding payer populations.

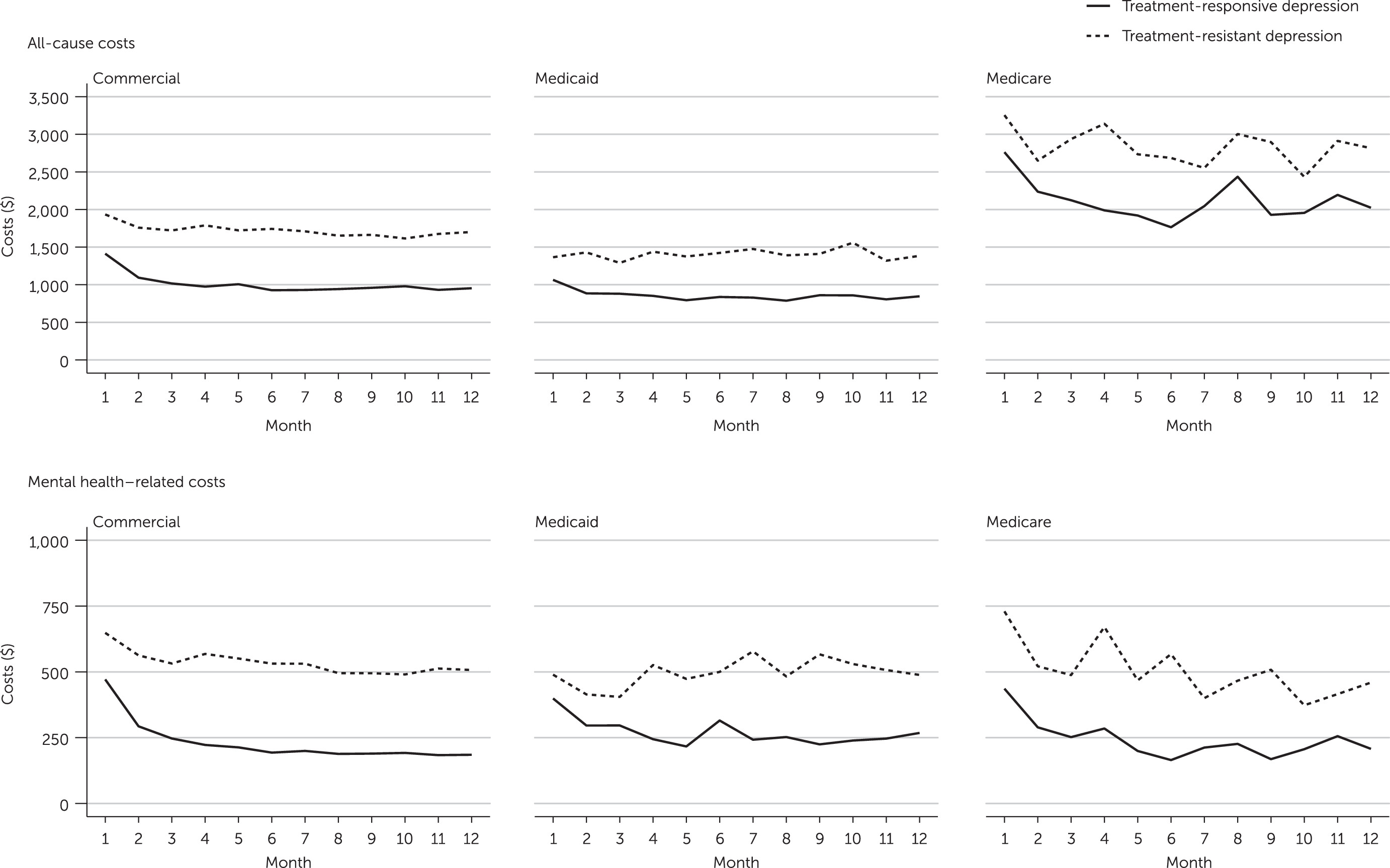

In addition, the study examined the time trend of health care costs, or the monthly changes in average all-cause and mental health–related health care costs during the 12-month follow-up period to understand the differential trends in costs associated with resource utilization by treatment-resistant depression status.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that across all three payer populations examined, patients with treatment-resistant depression had significantly higher health care resource utilization and costs, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression during the first 12 months after antidepressant treatment initiation. The incremental health care utilization burden of treatment-resistant depression was most pronounced among commercially insured patients, except for ED visits. Across the three payer populations, the incremental odds of having a mental health–related ED visit were highest among Medicare patients with treatment-resistant depression, compared with their counterparts with treatment-responsive depression. Across the three payer populations, the incremental all-cause cost burden was greatest among Medicare patients, whereas the mental health–related cost burden was most pronounced among commercially insured patients.

Our findings are consistent with past studies of the burden of treatment-resistant depression that examined commercially insured and Medicaid populations and found higher health care utilization among patients with treatment-resistant depression, compared with patients with treatment-responsive major depressive disorder (

12,

13). In addition, results for health care cost burden from the study reported here are in line with prior research, which estimated that commercially insured patients with treatment-resistant depression incur greater annual health care costs, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression (

10,

12). Further research is needed to quantify the incremental burden of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs, exclusive of mental health–related care.

This study adds to the growing body of research examining treatment-resistant depression burden by including a diverse sample of U.S. adults, including elderly Medicare recipients, who, to our knowledge, have not been separately evaluated before. We found that the incremental health care utilization and cost burden associated with treatment-resistant depression in the Medicare population was similar to or greater than in the Medicaid and commercially insured populations. This is the first comprehensive study of health care burden incurred by patients with treatment-resistant depression in all adult age groups (i.e., ages 18 and older). Thus these findings may inform future economic modeling work in a wider range of populations with major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression. Furthermore, our comparison of burden among patients with treatment-resistant depression and randomly selected patients with treatment-responsive depression involved a more representative comparison group, because the comparison was not limited only to patients with treatment-responsive depression who were very similar to patients with treatment-resistant depression, as has been the case in past studies that used matched controls; rather the comparison in our study was made against typical patients with treatment-responsive depression (

5,

9,

12).

Across the three payer populations, we observed that among patients with treatment-resistant depression there was a trend toward higher baseline utilization and costs, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression. In other words, patients with treatment-resistant and treatment-responsive depression exhibited differential resource use, even before the designation of treatment-resistant depression status. Moreover, the time trend analysis showed that higher health care costs incurred by patients with treatment-resistant depression in this study were observed right from the beginning of the follow-up period, before treatment-resistant depression was identified in most patients. One possible explanation for this trend is that patients with treatment-resistant depression may have higher baseline depression severity and comorbidity burden, as observed in the STAR*D trial, and so incur a higher cost burden from the start of treatment (

18,

19). Patients with treatment-resistant depression in our study showed greater comorbidity burden, and although depression severity status was missing for most patients, we observed higher severity on the basis of depression severity–related

ICD codes among patients with treatment-resistant depression, compared with patients with treatment-responsive depression (see table in

online supplement). Of note, the time trend analysis showed a high cost burden among patients with treatment-resistant depression at the time of first antidepressant treatment, which remained high throughout the follow-up period and which aligns with the expected severity course of patients with treatment-resistant depression. All groups except Medicaid patients with treatment-resistant depression experienced a decline in costs after the first month postindex. This decline was greater for patients with treatment-responsive depression, suggesting that these patients incurred decreased costs as they improved with antidepressant therapy. Collectively, these findings suggest that treatment-resistant depression is a health state that exists before a patient is identified as having treatment-resistant depression on the basis of inadequate response to treatment, and thus the findings underscore the need for early identification of treatment-resistant depression—ideally based on clinical criteria rather than treatment failures—to ensure close monitoring. Future work is needed to evaluate this relationship, because symptom severity data were missing for most patients in this analysis, and treatment-resistant depression status was inferred on the basis of pharmacy claims data.

Differences in incremental utilization and cost between patients with and without treatment-resistant depression were larger among commercial and Medicare populations, compared with the Medicaid population, possibly because of differences in patient characteristics and in plan benefit design. For example, the Medicare population represented only patients ages ≥65, and a higher proportion had a CCI score ≥2, compared with the Medicaid and commercial populations—indicating a greater number of comorbid conditions. Thus it is likely that Medicare beneficiaries had more physical illness at baseline, which led to higher utilization and subsequently higher average costs, compared with the Medicaid and commercially insured populations (see table in online supplement).

On the other hand, the Medicaid population represents low-income patients, who often have a higher prevalence of mental illness (

20). In this study, a larger proportion of Medicaid patients with and without treatment-resistant depression, compared with Medicare and commercial patients, had anxiety or other mental and behavioral health disorders. In addition, Medicaid patients both with and without treatment-resistant depression in this study had higher baseline mental health–related health care resource utilization, compared with the Medicare and commercially insured populations. However, several states have Medicaid behavioral health carve-outs, and more than 40% of Medicaid patients in this study also had health maintenance organization plans, which tend to be more restrictive than other health plans (

21). Potentially, the Medicaid population in this study had a greater burden of psychiatric illness, even among those without treatment-resistant depression, compared with the Medicare and commercially insured populations, and less generous insurance benefits would have limited even higher levels of resource use above this elevated baseline. If so, that would have led to a smaller incremental burden of treatment-resistant depression in the Medicaid population, similar to the results observed in this study. However, without more nuanced data and direct comparisons, we cannot be certain of the reasons behind such differences in magnitudes of burden.

The study had some limitations. It used administrative claims data, which lacked detailed sociodemographic, behavioral, and relevant clinical characteristics, such as socioeconomic status, presence or absence of support systems, alcohol or illicit drug use, and severity of depression at baseline. If any of these missing data were strong confounders for the assessment of treatment-resistant depression status and the health care utilization and cost outcomes, the findings of this study may be biased. We included CCI score and baseline all-cause annual health care cost in the regression models as proxy measures of disease severity and health status. However, some residual bias may still exist. We were further limited by a lack of information pertaining to medication compliance for each treatment prescribed. Treatment failure was defined on the basis of the patterns of filled prescriptions as treatment discontinuation or change in or augmentation of the current treatment with another line of therapy. However, clinical information about why a patient switched therapies or discontinued use of a specific line of treatment was not available through the claims data. Finally, our data were limited to Medicare beneficiaries who received supplemental insurance through former employers, and thus these results may not be representative of the general Medicare population.