Discharge planning practices that promote transition from inpatient psychiatric units to community-based care include communicating with outpatient clinicians, scheduling timely appointments for outpatient follow-up care, and forwarding discharge summaries to outpatient clinicians (

1–

4). Communication with outpatient clinicians and timely scheduling of outpatient follow-up appointments improve attendance rates at outpatient psychiatric services (

5–

9), and continuing care plans convey information that supports continuity of care and lowers the likelihood of relapse and readmission (

10–

16). These practices are widely accepted as standards of care for inpatient treatment (

17–

20).

Limited data exist, however, on the likelihood of patients’ receipt of such discharge planning practices, and available evidence from varied hospital settings suggests that rates at which providers complete these practices are low. One study found that inpatient medical-surgical clinicians communicated directly with outpatient clinicians for only 37% of discharges (

21). In another study, one-third of adults reported being discharged from a hospital without any follow-up arrangements (

22). Previous research has found that outpatient appointments are scheduled for 41%−67% of patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric units (

7,

23), and results from one study indicated that inpatient psychiatric clinicians communicated with outpatient providers for only 66% of discharges (

5). A 2007 review found that outpatient primary care clinicians reported receiving a continuing care plan within 1 week of discharge for only 15% of discharged patients (

24), although a recent review noted that discharge summaries were available to primary care providers within 48 hours for 55% of discharged patients (

25).

Most of these studies had significant methodological flaws that limited their generalizability, including a small sample size, selection biases, and failure to test for reliability of reporting. To better inform targeting of quality improvement efforts, research is needed to understand the prevalence of psychiatric inpatient discharge planning practices and to identify factors associated with low rates of discharge planning in larger and more broadly representative populations.

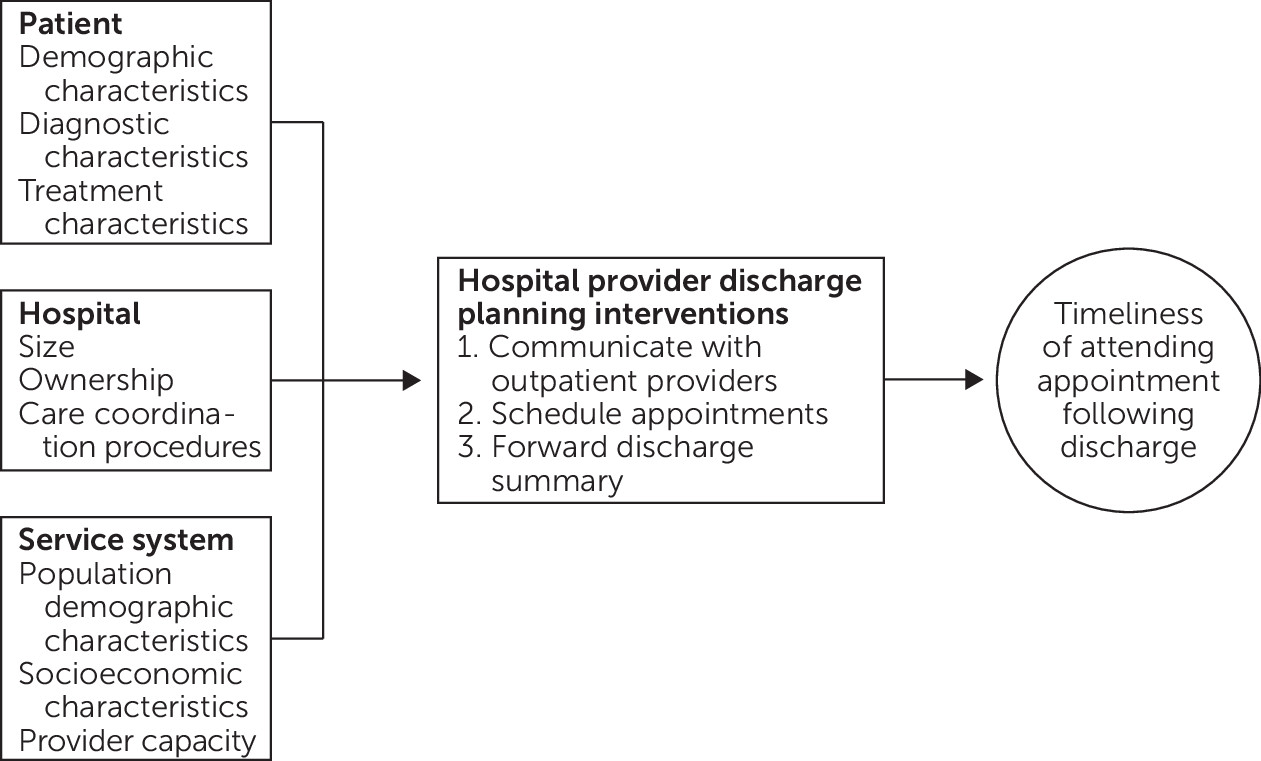

This study examined a key discharge planning practice: scheduling by inpatient psychiatric providers of outpatient appointments with mental health providers after discharge. We examined data from a large cohort of inpatient psychiatric admissions and report the proportion of patients who received this practice along with patient, hospital, and service system characteristics associated with receipt of the practice. On the basis of a conceptual model (

Figure 1), we hypothesized that patients who had short inpatient stays or had diagnoses of less severe psychiatric disorders would be less likely to have an outpatient appointment scheduled, because clinicians would assume that such patients were more likely to follow through with outpatient clinicians who cared for them previously. We further anticipated that smaller or nonteaching hospitals would have fewer staff available to schedule outpatient appointments and that their patients therefore would be less likely to receive this discharge planning activity. Moreover, we expected that patients who resided in areas with greater constraints on economic or mental health resources would also be less likely to have an outpatient appointment scheduled as part of their discharge plan.

Methods

Data Sources

Data were obtained from four primary sources: 2012–2013 New York State (NYS) Medicaid claims records, the 2012–2013 American Hospital Association Annual Survey (

26), the 2012–2013 Health Resources and Services Administration Area Resource File (

27), and a 2012–2013 NYS Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organization (MBHO) discharge file created during a quality assurance program in which NYS contracted with five MBHOs in geographically distinct regions to review discharge planning practices for fee-for-service inpatient psychiatric admissions. NYS hospital providers were required to notify the regional MBHO of every Medicaid psychiatric inpatient admission and provide specific information to the MBHO regarding the patient’s treatment and discharge plans. The MBHOs, which were not applying medical necessity criteria and not paying providers for the hospital care during this period, were required to offer hospital providers the option to submit the information by telephone, fax, or secure Web-based portal.

Patient eligibility criteria included age <65 years, admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit in the period from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2013, with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder, discharged to the community, enrolled in Medicaid for at least 11 of the 12 months prior to admission, no Medicare eligibility, and inpatient length of stay of ≤60 days. For patients with more than one inpatient psychiatric admission during 2012–2013, only the initial admission was included. (A consort diagram describing the creation of the study sample is included in an online supplement to this article.) After matching the MBHO discharge file with NYS Medicaid claims records and applying all eligibility criteria, the final sample included 18,185 inpatient psychiatric discharges. The NYS Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study and granted a waiver of individual consent.

Dependent Variables

Outcome variables were created from the MBHO data file. The MBHOs were required to report whether, for each discharge, the inpatient psychiatric team scheduled a mental health outpatient appointment, communicated with a current or previous outpatient clinician, and forwarded a discharge summary to an outpatient clinician. We also created a composite dichotomous variable defined by provision of all three discharge planning practices. To assess the reliability of the reported data and operationalize definitions of the discharge planning practices, we completed a reliability study in which data from MBHO reports were compared with data extracted from inpatient medical records (N=214) from two hospitals (

28). Only one of the three discharge planning practice variables met a level of moderate reliability (κ≥0.4) for inclusion in regression models reported below: scheduling an outpatient appointment with a specified date after discharge.

Independent Variables

Independent variables included patient, hospital, and regional service system characteristics that previous research suggested could affect discharge planning and postdischarge continuity of care for patients with psychiatric disorders (

29,

30). Patient-level variables from Medicaid claims included demographic factors, a primary inpatient discharge diagnosis, and a diagnosis of a co-occurring substance use disorder at discharge. Previous engagement in psychiatric outpatient services was assessed with claims data indicating receipt of outpatient services listing a primary mental disorder diagnosis or mental health service code, and service for each patient was categorized as active (at least one service in the 30 days preadmission), recent (at least one service in the 12 months preadmission but no services in the 30 days preadmission), or none (no services in the 12 months preadmission). Additional patient characteristics included homeless at admission and burden of co-occurring medical conditions, assessed with an Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI). We used established algorithms to create an ECI index score for each discharge on the basis of clinical diagnoses reported in inpatient and outpatient claims for all Medicaid services during the 12 months before admission (

31,

32).

Hospitals were characterized on the basis of size, provision of outpatient psychiatric services, hospital ownership, percentage of total annual discharges enrolled in Medicaid, and medical resident teaching status. Information from NYS administrative databases, including the NYS Medicaid Program, the NYS Department of Health Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System, and the NYS Office of Mental Health’s Mental Health Automated Record System, was used to create additional variables characterizing the hospitals. These “case-mix” variables included the percentage of psychiatric discharges with a substance use disorder diagnosis and the percentage of psychiatric patients with two or more psychiatric hospitalizations during the period. Area Health Resource File data characterized counties in which patients resided with respect to regional mental health resources, poverty, and urban-rural classification. An MBHO variable was added to distinguish among the five different MBHOs.

Analysis Plan

The proportion of inpatients not having an appointment scheduled was determined overall and stratified by each patient, hospital, and service system characteristic. Odds ratios (ORs) with 99% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each characteristic. Adjusted ORs (AORs) were calculated by using logistic regression analyses and describe the effect of each variable on the probability of not having an outpatient appointment scheduled, when all other covariates were controlled for. Average marginal effects (AMEs) were also provided as a measure of an effect on the probability scale. Because patients were nested within different hospitals, the observations were nonindependent. Accordingly, generalized estimating equations were used to account for the clustering of observations within hospitals. We considered AORs with 99% CIs that did not include 1.0 and AMEs with 99% CIs that did not include 0.0 to be statistically significant, while also noting AORs and AMEs with p>0.01 and p<0.05. In this large, exploratory study, no adjustments were made to the many CIs and p values, which should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Results

Hospital psychiatric staff scheduled a follow-up outpatient appointment with a mental health provider for 14,503 out of 18,185 discharges (79.8%) for which complete information was available. (Descriptive data related to the other discharge planning practices [i.e., communication with an outpatient clinician and forwarding a discharge summary], along with descriptive data and regression models for the composite variable describing whether the patient received all three discharge planning practices that met our reliability threshold, are reported in the online supplement.)

Table 1 reports the percentages of patients who did not have an outpatient mental health appointment scheduled, stratified by patient, hospital, and service system characteristics. In the adjusted logistic regression model, patient characteristics that were statistically significantly associated with not having an appointment scheduled included being older (reference: ages 4–12) and having short (≤4 days) or long (31–60 days) inpatient lengths of stay (reference: 5–14 days) (

Table 1). In unadjusted models, non-Hispanic Black and Puerto Rican–Hispanic patients were more likely than non-Hispanic White patients not to have an appointment scheduled, although these associations were largely eliminated in the adjusted models; in the adjusted model, being Puerto Rican–Hispanic was statistically significantly associated with being more likely to have an appointment scheduled. Other variables associated with not having an outpatient appointment scheduled included being homeless on admission, having a diagnosis of a co-occurring substance use disorder, having high levels of medical comorbid conditions (Elixhauser score ≥4), and not being engaged in psychiatric outpatient services in the month before admission. Patients with bipolar disorder were also more likely than patients with schizophrenia not to have an outpatient appointment scheduled (p=0.02).

None of the hospital characteristics were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of having an outpatient appointment scheduled. For system characteristics, the MBHO variable was significant (reference: Western Region MBHO); patients treated in hospitals reviewed by the New York City and Hudson River MBHOs had a higher probability of having aftercare appointments scheduled. A similar tendency was noted for the Long Island MBHO (p=0.03). Patients treated in hospitals located in large metropolitan regions (reference: medium metropolitan regions) also tended not to have an outpatient appointment scheduled (p=0.03).

Discussion

In 2012–2013, more than 20% of Medicaid patients discharged from a hospital psychiatric unit in NYS did not have an appointment with an outpatient mental health provider scheduled at the time of their discharge. This quality-of-care gap is concerning, given the known clinical risks associated with the period immediately after discharge from inpatient psychiatric units, including relapse and hospital readmission (

7,

13,

33–

37), homelessness (

38,

39), violent behavior (

40,

41), criminal justice involvement (

42,

43), and all-cause mortality, including suicide (

44–

46).

We hypothesized that several patient, hospital, and service system characteristics would be associated with the probability of patients not having an outpatient appointment scheduled. Our findings indicated that patient characteristics were more likely than hospital or service system characteristics to predict whether appointments were scheduled: seven patient-level variables were statistically significant in the adjusted models, none of the hospital-level variables were significant, and only one of the service system variables was significant. Patient characteristics appeared to be more critical determinants of whether patients received adequate discharge planning and should be primary areas of focus for activities aimed at improving care quality in the hospital.

We hypothesized that patients who had shorter inpatient stays and primary diagnoses of less severe psychiatric disorders would be less likely to have an outpatient appointment scheduled. These hypotheses were partially supported: no significant differences were detected in discharge planning practices among patients with different primary diagnoses; however, patients with short stays (≤4 days) and those with long stays (31–60 days) were more likely than those with stays of 5–14 days not to have an appointment scheduled. Patients with short stays may be less likely to receive discharge planning because this group includes patients who sign out against medical advice or otherwise do not wish to pursue treatment. Those with longer stays, however, are more likely to have persistent symptoms or complex psychosocial circumstances that require extended inpatient care. These characteristics may also make discharge planning more complex and increase the likelihood that timely follow-up appointments are not scheduled. This finding suggests another important focus for hospital quality improvement activities to ensure high-need patients receive adequate discharge planning.

Patients who had co-occurring substance use, were homeless, or were not engaged in care in the month preadmission were more likely not to have an outpatient appointment scheduled. In previous research, these characteristics were also strong predictors of failed care transitions and poor outcomes in the period immediately after discharge (

29,

30,

47). Individuals with a co-occurring substance use disorder were more likely to be discharged without adequate access to community-based treatment for co-occurring disorders, making them vulnerable to relapse, substance use, and further disengagement from care (

48). Homeless individuals are similarly at risk because of their lack of stable supports in the community (

49), and individuals who previously did not engage in community-based care are more likely to continue to be disengaged without more intensive follow-up (

29,

30). Inpatient clinicians should aim to ensure that these patients receive adequate discharge planning, and many will require more intensive care transition interventions, which have been shown to improve continuity of care for high-risk patients (

50–

57).

Inpatient clinicians were less likely to schedule appointments for patients with high levels of comorbid conditions. Because this study included only patients who were discharged to the community, this finding cannot be explained by transfers to other hospital units or residential treatment facilities. Inpatient clinicians may believe that patients with high levels of comorbid conditions have established networks of community-based medical providers who will manage postdischarge care without the need for timely aftercare from psychiatric providers. Nevertheless, this practice should be considered inadequate discharge planning, given the importance of integrating care for these vulnerable patients.

We also hypothesized that patients treated in smaller or nonteaching hospitals or who resided in areas with greater economic or mental health resource constraints would also be less likely to have an outpatient appointment scheduled. Hospitals that served higher proportions of patients with Medicaid had lower rates of scheduling outpatient appointments, although in the adjusted logistic models this variable and none of the other hospital variables were associated with the likelihood of scheduling an appointment. In contrast to what we anticipated, patients treated in teaching hospitals were more likely not to receive complete discharge planning (see table in online supplement). This finding was counterintuitive, given the important educational role and availability of trainees to support care and treatment planning. However, many teaching hospitals are located in urban areas and treat patients with higher rates of poverty and other factors that may complicate clinicians’ discharge planning practices.

Despite known shortages of mental health providers in rural and underserved communities, the service system variables related to poverty and density of mental health workers were not significantly associated with the likelihood of having an outpatient appointment scheduled. The variable denoting the MBHO that reviewed admissions for each defined region of the state was associated with discharge planning practices; the New York City MBHO reported lower rates of scheduling appointments. This finding may reflect the greater numbers of patients in New York City hospitals who did not receive discharge planning because these hospitals also provided outpatient psychiatric services. Anecdotal reports indicate that many New York City hospitals operate walk-in clinics for outpatient follow-up appointments; hospitals with such clinics may have had lower rates of appointments scheduled because these clinics were seen as obviating the need for discharge planning.

The main limitation of this study was related to the reliability of the discharge planning practice variables; we did not model two of the discharge planning practices because of low correlations between MBHO reports and documentation of the specific practices in patients’ medical records from two hospitals in our reliability study (descriptive data regarding these practices are available in the online supplement). Another limitation was the study’s naturalistic design, which limited inferences regarding causality because of the potential for unmeasured confounding factors.

We also did not have discharge planning data for the entire population of Medicaid patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric units during the 2012–2013 study period. The sample comprised 20.8% of NYS Medicaid fee-for-service hospital psychiatric admissions with a mental disorder as the primary diagnosis and included representation from 105 of 106 statewide hospitals that admitted Medicaid fee-for-service patients in 2012–2013. The greatest numbers of excluded cases were patients with diagnoses other than mental disorders, readmissions, cases not reviewed by MBHOs, and cases not meeting the preadmission Medicaid enrollment criteria. Patients with primary diagnoses other than mental disorders represented admissions to substance use disorder treatment programs, which were not the population of interest for this study. Readmissions were excluded to avoid bias associated with data from duplicate patients. Patients with admissions not reviewed by MBHOs, which included admissions for both mental health and substance use treatment, were more likely to have been younger and male and to have had shorter lengths of stay, which may represent a group less likely to receive discharge planning.

Patients were also excluded when they did not meet our requirement of Medicaid enrollment for 11 of the 12 months before the index admission. During the study planning period, a preliminary analysis indicated that this Medicaid enrollment threshold allowed for consideration of 76% of all Medicaid admissions in 2012–2013. We considered lowering the requirement to 8 months, which would have yielded 86% of the original cohort; however, it would have included a significant number of cases with no available data for up to one-third of the period of interest before admission. For this reason, we kept the selection criterion of enrollment for 11 out of 12 months. It is unclear whether cases excluded because of this criterion may have been more or less likely to receive discharge planning.