Severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression, often leads to large and long-lasting human costs. These include a lower level of functioning, low self-esteem, loss of earnings, and financial deprivation (

1–

6). The evidence-based program Individual Placement and Support (IPS) aims to help persons with severe mental illness obtain and keep work and is in this regard superior to other vocational rehabilitation programs (

7–

9). The IPS program is based on eight empirically supported principles: competitive employment as a goal; rapid job search; program eligibility based on the participant’s choice; attention to the participant’s preferences regarding type of job and disclosure of psychiatric illness to potential employers; integration of IPS with mental health services; time-unlimited, individualized support after a job is obtained; social insurance and benefits counseling; and systematic job development and engagement with employers.

IPS is frequently described as a recovery-oriented intervention (

10,

11), not only because it endeavors to help people get jobs, but more fundamentally, because it is aimed at supporting people in living an independent functionally engaged life. Moreover, principles of IPS (such as attention to participants’ preferences; time-unlimited, individualized support; and rapid job search) might be expected to foster hope, self-determination, and inclusion (

11). Nevertheless, empirical support for IPS as a recovery-promoting practice is unclear, and there is a need to address this question.

The concept of recovery is often divided into personal and clinical recovery. Personal recovery focuses on living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life, even with limitations caused by the illness, whereas clinical recovery focuses on improvements in mental health symptoms and level of functioning (

12–

14). When investigating whether IPS is associated with improvements in recovery, other than improved work functioning, it should be borne in mind that obtaining employment has been connected with modest improvements in self-esteem, quality of life, and other areas of functioning (

15,

16). Therefore, it is worthwhile exploring whether IPS is associated with additional benefits to recovery beyond those of employment. The aim of this systematic literature review was to assess the associations between IPS, employment, and personal and clinical recovery among persons with severe mental illness at 18-month follow-up. It was assumed that 18 months was a sufficient time span to measure these associations.

The following hypotheses were tested. IPS is more strongly associated with personal recovery (self-esteem, self-efficacy, hope, empowerment, and quality of life) and clinical recovery (symptoms of depression, negative and psychotic symptoms, anxiety, and level of functioning), compared with services as usual (interventions not using IPS or modified or adapted versions of IPS). IPS is more strongly associated with personal and clinical recovery, compared with services as usual, when outcomes are stratified by number of weeks worked. Number of weeks worked, independent of IPS, is associated with increases in personal and clinical recovery.

Methods

This review followed an a priori–defined protocol published on PROSPERO, (

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero; protocol CRD42017055587). The protocol was developed following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) (

17). Guided by this protocol, a literature search was conducted, and meta-analyses of data from eligible studies were utilized to answer the hypotheses. If the hypotheses could not be answered by using meta-analyses, study authors were contacted and asked to provide data for the analyses of pooled original data.

Literature Search

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted on June 21, 2017, and updated on January 11, 2019, by two librarians at the University of Southern Denmark. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and OTseeker. Additionally, ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP search portal) were searched for unpublished material. No limitations regarding year of publication or language were imposed. Bibliographies from primary studies and review articles were hand searched. (A figure presenting the updated search strategy is included in an online supplement to this article.)

Inclusion criteria.

Scales used for outcome measures in the studies included in this review were psychometrically described in peer-reviewed journals and used without modifications. Study participants were unemployed adults of either sex and ages 18–65, with severe mental illness (defined as schizophrenia; schizoaffective, schizotypal, or delusional disorders; bipolar disorder; or severe depression) according to

ICD-10 or

DSM-5 (

18,

19).

Studies included in this review compared IPS with services as usual or other interventions that did not use IPS or approaches derived from it. IPS was evaluated with regular fidelity reviews and achieved good or fair fidelity (

20,

21). The included studies measured outcomes at 18-month follow -up. The studies included outcome measures related to self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, hope, self-efficacy, depression, psychotic and negative symptoms, anxiety, and level of functioning.

Search process.

The electronic literature search resulted in identification of 2,167 unique citations (see online supplement). A total of 2,099 citations were excluded on the basis of title and abstract screening, leaving 68 articles for full-text review. The primary reasons for exclusion after full-text review were that the intervention failed to fulfill the IPS fidelity criteria or that results were not measured at 18-month follow-up. In the systematic review, eight RCTs were included (

16,

22–

31). Of those, six trials were found eligible for meta-analysis (

16,

22–

26,

29–

31), and five trials were found eligible for pooled original data (

16,

22–

25,

30,

31). Two of the eight trials could not be analyzed by using meta-analyses, and the study authors of those trials were unable to provide data for the analyses of pooled original data (

27,

28). (Details on the selection process, data extraction, and study characteristics are provided in the online supplement.)

Exposure Variables

IPS and services as usual were exposure variables. Moreover, number of weeks in employment was used as an exposure variable. This variable was chosen because the IPS intervention encourages participants to find the right work-life balance, instead of aiming at the more work, the better (

32). The variable number of weeks in employment was defined by three categories: no employment, fewer than the median weeks in employment, and more than the median weeks in employment. Median weeks in employment was defined according to each trial on the basis of the median number of weeks worked for all participants who worked at least 1 week.

Overall, services as usual was defined in the same way in the included studies—namely, as traditional vocational services. These services were facilitated by mental health professionals or by public services on the basis of an assessment of patients’ rehabilitation needs. Services as usual included prevocational activities, such as voluntary jobs before placement in regular jobs, and thus these services were based on the more traditional principles of “train and place.”

Outcome Measures

A table in the online supplement provides details on the scales used by the six trials. Hope and self-efficacy outcomes were excluded, because these were measured in only a single trial (

22,

31).

Statistical Methods

The meta-analyses were conducted on standardized mean differences (SMDs) calculated from the means and standard deviations in the raw data for self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, depressive symptoms, negative and psychotic symptoms, anxiety, and level of functioning. Kukla and Bond (

29) did not provide raw data but reported means and SDs suitable for meta-analyses. The effect sizes used in the meta-analyses were calculated as the raw difference in the mean scores between IPS and services as usual at 18-month follow-up divided by the pooled SD.

Descriptive baseline data for pooled original data are presented by using means and SDs for numerical variables and Ns and percentages for categorical variables. For analyses of pooled original data, the numerical outcomes (self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, psychotic and negative symptoms, anxiety, and level of functioning) were all standardized within each study to have one common scale (mean=0, SD=1) when treatment effects for the forest plots were estimated. These standardized effect estimates are the same as those used in the meta-analysis. These variables were analyzed by using linear regression with robust standard errors. For depressive symptoms, a standardization of the numerical baseline score was used to adjust for baseline severity. Depressive symptoms were categorized into three levels (mild, moderate, and severe); the proportional-odds model was used, and log scale estimates are reported. All estimates derived from pooled original data were adjusted for age, gender, site, and trial, as well as the baseline score of the variable in question.

Analyses were carried out on numerous secondary and exploratory outcomes. Therefore, the alpha level of significance was Bonferroni-corrected by number of outcomes, which led to a level of significance of p<0.007. For all analyses, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used. Heterogeneity in effect estimates was assessed using the I

2 statistic (

33).

Results

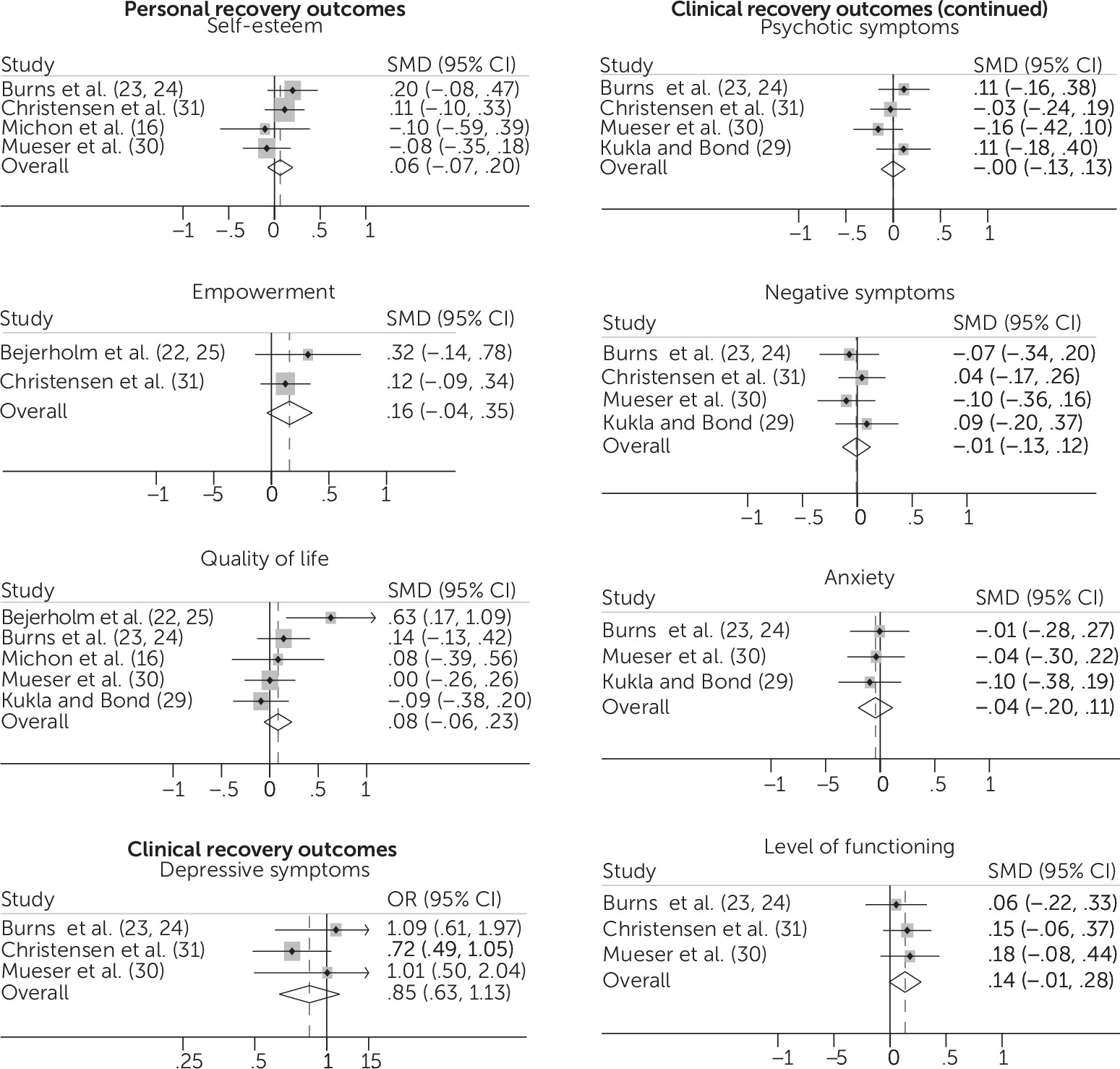

Meta-Analysis

As noted above, six trials (N=1,243 participants) reported data suitable for meta-analyses: Bejerholm et al. (

22,

25), Burns et al. (

23,

24), Bond et al. (

26), Kukla and Bond (

29), Christensen et al. (

31), Michon et al. (

16), and Mueser et al. (

30). Meta-analyses indicated that the associations between IPS and clinical and personal recovery were no stronger than the associations between services as usual and clinical and personal recovery (Figure

1). Overall effect sizes were small, ranging from –0.04 to 0.16, 95% CI=–0.2, 0.35. No heterogeneity above 0.0% was observed, except for quality of life (I

2=45.9%, p=0.116).

Pooled Original Data

Authors from five of eight trials provided raw data for pooled analyses: Bejerholm et al. (

22,

25), Burns et al. (

23,

24), Christensen et al. (

31), Michon et al. (

16), and Mueser et al. (

30).

Characteristics of Study Population From Pooled Original Data

A total of 1,488 participants were included from the five studies. Participants with diagnoses other than psychotic or affective illness were excluded (N=52). The same applied to participants with all missing data on the outcomes considered (N=337). Moreover, 43 participants were excluded because of missing data on number of weeks worked. Thus the population for the studies providing raw data consisted of 1,056 participants.

Of this study population, most were male, and the mean age was 35 (Table

1). Diagnoses spanned schizophrenia or psychotic illnesses, bipolar disorder, and depression. The number of participants receiving IPS was 595 (56%) (data not shown in table). Of the 1,056 participants, the numbers employed were as follows: zero weeks, N=682 (65%); fewer than the median weeks, N=190 (18%); and more than or equal to the median weeks, N=184 (17%).

Associations Between IPS Combined With Weeks in Employment and Recovery

No associations were observed between IPS combined with weeks in employment and clinical and personal recovery (Table

2). Among participants working zero weeks, a tendency was noted for negative symptoms to improve more for the group receiving services as usual group than for the IPS group (SMD=−0.20, p=0.017). After Bonferroni correction, this tendency was not significant.

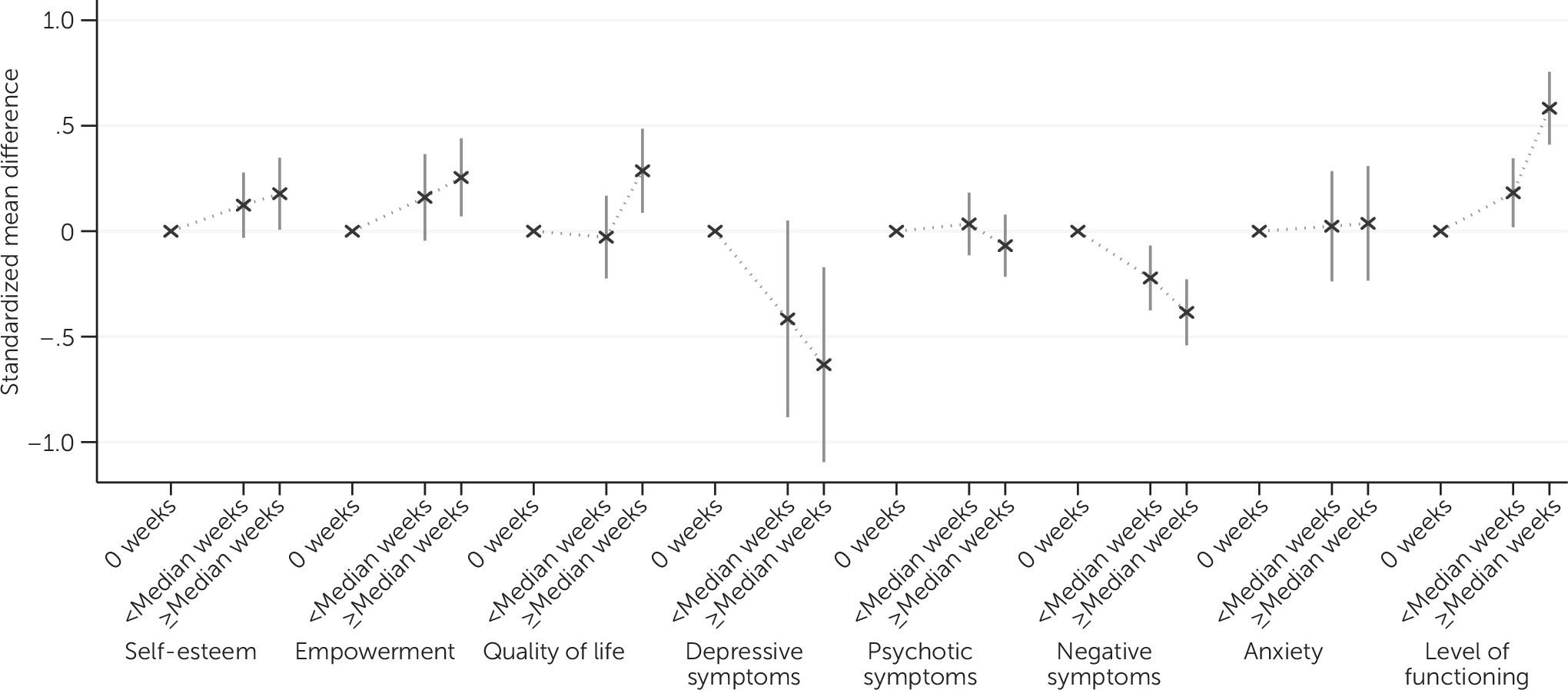

Associations Between Weeks of Employment and Changes in Recovery Independent of IPS

Improvements were found for negative symptoms among employed participants, compared with participants who were not employed (employed fewer than the median weeks, SMD=−0.25, 95% CI=−0.40, 0.09; employed more than or equal to the median weeks, SMD=−0.41, 95% CI=−0.56, –0.26) (Figure

2; see table in online supplement). Additionally, level of functioning improved for employed participants, compared with those not employed (employed fewer than the median weeks, SMD=0.23, 95% CI=0.07, 0.39; employed more than or equal to the median weeks, SMD=0.59, 95% CI=0.42, 0.77). Quality of life improved for participants employed for more than the median weeks (SMD=0.34, 95% CI=0.14, 0.54), compared with participants employed fewer than the median weeks (SMD = 0.03, 95% CI=–0.16, 0.22).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to assess the associations between IPS, employment, and personal and clinical recovery among persons with severe mental illness at 18-month follow-up. The aim was considered to be best answered by means of meta-analyses and analyses of pooled original data. Six trials provided data for the meta-analyses, and five trials provided data for the pooled data analyses, respectively.

Associations Between IPS and Recovery

The analysis suggests that IPS has no stronger association, compared with services as usual, in improving personal and clinical recovery. Meta-analyses showed small effect sizes in all measured outcomes, indicating that any effects of IPS on personal and clinical recovery were restricted to a narrow region of small effects. Results from pooled original data regarding whether the combination of IPS and competitive employment was connected to a further increment in recovery, compared with employment alone, showed no further enhancement.

A number of causes should be considered in explaining this relation. First, IPS does not explicitly focus on the items measured in the recovery scales. Employment is the core aim of IPS and thus the proximal outcome, whereas clinical and personal recovery are distal outcomes and less directly affected by IPS. Thus it is likely that IPS is limited to affecting its core aim only. Furthermore, a relatively large group of IPS participants did not succeed in finding employment, and a substantial portion of the employed participants attained short-term jobs at a low wage, which might also contribute to null findings in the recovery outcomes. Second, methodological challenges may have affected the outcomes. It is worth considering whether self-reported rating scales, which are used in data collection to measure outcomes such as self-esteem and empowerment, actually capture the intended phenomena. Perhaps self-reported rating scales are too crude and large-meshed to capture important details. Third, recovery outcomes might be affected by numerous factors in a person’s life other than IPS—e.g., interpersonal relationships, side effects of medication, or other options made available from community mental health centers or volunteer organizations. Consequently, changes derived from IPS alone might be difficult to demonstrate.

One way to handle these challenges might be to introduce other methodologies. Research traditions within phenomenological psychopathology draw on other methods. In such approaches, phenomena are studied by using video-recorded, semistructured interviews, and the sample size varies from 50 to 100 participants, allowing for use of both qualitative and statistical analysis (

34). Considering new methods for investigating associations between IPS and personal and clinical recovery might lead the IPS literature into new pathways. Finally, it is worth mentioning that in the trials selected for this study measurement of the effect of IPS and employment on recovery was not their primary objective. We believe that trials that aim to investigate the impact of IPS on personal and clinical recovery are warranted to clarify and address causality in this regard.

Associations Between Employment and Recovery

The study found reductions in negative symptoms among employed participants, compared with participants not working. The results were within the same range as those in a study by Petersen et al. (

35) on integrated psychiatric treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Those authors concluded that the effect size was small but of clinical relevance. Even though the reduction in negative symptoms found in the study reported here was small, it could still be important for participants and clinicians, considering that most antipsychotic medication is not superior to placebo in treating negative symptoms (

36). Moreover, because of the great variety of adverse side effects of antipsychotic medication, it is important to have nonpharmaceutical alternatives available to help improve negative symptoms.

As in other studies, employed participants improved in level of functioning, compared with participants who were not employed (

37). This finding should be interpreted cautiously, because occupational functioning, in particular, forms part of the evaluation when level of functioning is assessed (

38). Changing employment status from unemployment to employment causes noticeable increases in GAF scores of between 5 and 10 points—an increase considered to be of clinical importance (

39).

Participants employed for more than the median weeks improved in quality of life. This corresponds to the moderate effect size reported by van Rijn et al. (

40).

It is beyond the scope of this study to draw conclusions about causality. Whether employment induced improvements in the above-mentioned outcomes or whether improvements in outcomes led to increases in employment capacity cannot be decided. However, on the basis of these findings and those of previous studies, it is worth discussing whether IPS should be recommended to community mental health services in general. The results of this study showed that the IPS intervention by itself did not support clinical and personal recovery outcomes. This finding is in accordance with those from previous meta-analyses on supported employment (

9,

40). On the other hand, the results showed no negative clinical implications connected to participation in IPS. Just as important, results pointed out important associations between employment and recovery outcomes, such as negative symptoms and quality of life. These results, together with evidence from other studies, reviews, and meta-analyses convincingly showing that IPS is the most effective rehabilitation service to help persons with severe mental illness achieve competitive employment, point toward a recommendation that mental health services implement IPS. Future research is needed regarding causal relationships between employment and recovery outcomes.

Strength and Limitations

The study was based on a comprehensive systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed at finding all possible studies performed in the area. Even though the number of studies in the meta-analysis was small, some studies were new and not included in older meta-analyses. Moreover, this meta-analysis analyzed only studies in which the intervention was IPS. Most other reviews and meta-analyses included a variety of supported employment services. The findings of associations between IPS, employment, and personal and clinical recovery were obtained through pooling original data, which permitted adjustments for potential confounders and which would not have been possible in a meta-analysis. The five studies that provided raw data all achieved good and fair fidelity, and study quality was generally good, although three of five studies did not use blinded assessors, which may have compromised outcome reporting and produced overestimated effect sizes.

The studies included four European (

16,

22–

25,

31) and one American (

30) RCT. Because one European trial investigated effectiveness of IPS in six European countries (

23,

24), data were from a total of ten countries, contributing to high generalizability. Authors of three studies did not provide raw data (

27–

29). In addition, these studies reported no effects on recovery when IPS was compared with services as usual. Thus inclusion of the three studies would probably not have changed the effect; however, it could have improved power in the analyses. Even though the generalizability was high, the trials represent western countries only (United States and European countries). Associations between IPS, recovery, and employment in nonwestern cultures remain to be determined.

The studies did not use identical scales for outcome measures, i.e., different scales were used in measuring psychotic and negative symptoms. Thus a standard conversion was applied. The numerical outcomes were all standardized to limit the introduction of bias from varying scales and variances; for example, a higher variance in one study would lead to a disproportionate weight given to that study in the overall estimates.

This review examined various recovery outcomes in order to broadly span the topic. However, the multiple outcomes limited the strength of the analyses by increasing risk of type 1 error. This was addressed by a Bonferroni correction (p≤0.007). The review did not succeed in addressing all outcome measures, because hope and self-efficacy were measured in only a few studies.

The studies included were those in which outcomes were evaluated only after 18 months, which was a pragmatic choice for this review. In addition, it would have been preferable to examine associations between IPS, employment, and recovery according to shorter follow-up periods—e.g., 6 or 12 months. This would have expanded the already large number of outcomes and further increased the risk of type 1 error.

Information on race and ethnicity was not reported, making it difficult to determine whether differences in outcomes might have existed across racial or ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions

The study found that at 18-month follow-up, associations between IPS and clinical and personal recovery were no stronger than they were for services as usual. The study found associations between weeks in employment, independent of IPS, and improvements in negative symptoms, level of functioning, and quality of life, but causality could not be addressed. The combination of IPS and competitive employment did not further enhance recovery outcomes, compared with employment alone. Future studies should focus on causality between negative symptoms, quality of life, and employment among persons receiving IPS.