Off-label prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics has played a large role in the growth of their utilization (

5). The uncertain or modest benefit associated with the utilization of second-generation antipsychotics for off-label indications (

6) and the drugs’ significant risk for cardiometabolic morbidity, including diabetes and cardiovascular disorders (

7), call into question the appropriateness of the practice (

8,

9). The risk-to-benefit ratio of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics is particularly poor for Black and Latino adults, whose baseline risk for cardiometabolic disease is generally larger than that of Whites; however, the factors associated with health care disparities among racial-ethnic groups may act as a buffer. Moreover, the economic burden associated with the growth in utilization of second-generation antipsychotics has been largely borne by the two main public payers, Medicaid and Medicare (

10,

11).

Because off-label prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics is at best an inefficient use of resources and at worst increases the potential for harm exceeding the likely benefits of these medications, particularly for racial-ethnic minority groups, the practice constitutes overuse and, as such, low-value care (

12). For budget-constrained public payers, off-label utilization may consume limited resources that might otherwise be used to finance higher-value care. Public payers vary in their use of utilization management strategies and incentives to shape prescription drug utilization for Medicaid, Medicare, and dually eligible beneficiaries, and they also vary in their drug-purchasing policies and ultimate costs. In addition, off-label utilization and costs may be affected by patients’ characteristics associated with cardiometabolic risk and by delivery system factors that vary across states and over time. Policy makers have an incentive to understand and reduce off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics, yet little is known about variation in off-label utilization by race-ethnicity, distinguishing between the largest non-White groups (i.e., Blacks and Latinos), or by payer because most studies have used payer-specific data. Moreover, no information is available on recent trends in off-label utilization and costs in the U.S., and only limited information exists on the typical doses used in off-label regimens.

Here, we sought to expand and update the evidence on the prevalence, temporal trends, and factors associated with off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics among Medicaid, Medicare, and dually eligible adult beneficiaries in four U.S. states with racially and ethnically diverse beneficiary populations and varying payer use of tools to manage medication access. Our primary goals were to generate evidence of the likelihood of off-label utilization by race-ethnicity and payer and to determine whether any association between off-label utilization and race-ethnicity is modified by payer. We hypothesized that beneficiaries who belong to racial-ethnic minority groups would be less likely to have off-label utilization, that payer would modify this association, and that off-label utilization would vary across states. We believe this evidence will enable the design of payer-specific policy interventions aimed at reducing off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics, with a special focus on those at greatest risk for harm from this practice.

Methods

Study Population and Design

The study population included non-Latino White, non-Latino Black, and Latino adults ages 18–64 years, having fee-for-service Medicaid, Medicare, or dual Medicaid-Medicare coverage and living in California, Georgia, Mississippi, or Oklahoma, who filled at least one prescription for any second-generation antipsychotic medication between July 1, 2008 (fiscal year 2009), and June 30, 2013 (fiscal year 2013). We selected these states because of the racial-ethnic diversity of their publicly insured populations. Data sources included Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) and Medicare data sets for calendar years 2008–2013.

The analyses focused on fee-for-service beneficiaries because of our interest in variability across payers, absent effects related to managed-care plans’ variable use of utilization management strategies. Further, managed-care data are less complete than fee-for-service claims data for the earlier years of our study period.

We tracked beneficiaries during the study period and constructed a retrospective repeated panel of second-generation antipsychotic prescription person-months. Beneficiaries who filled prescriptions for second-generation antipsychotics, whom we refer to here as second-generation antipsychotic users, contributed person-months in each fiscal year if they were continuously enrolled during the 12-month period comprising 6 months preceding and 6 months following the prescription. Beneficiaries were allowed to switch payer as long as they did not have enrollment discontinuities. (Further details on the study population and design are available in an online supplement to this article.) The study was reviewed and approved by RAND Corporation and Harvard Medical School.

Measures

Outcomes.

Our primary outcome was monthly off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics, defined as observation of any off-label second-generation antipsychotic prescription filled during the person-month. We defined off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics as the absence of schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, or severe major depressive disorder (as a proxy for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder) during the 6-month periods preceding and following the prescription. Given the chronicity of these three serious mental illnesses, we classified all future second-generation antipsychotic person-months as on-label, that is, i.e., we did not reassess for presence of these disorders. For mood disorders, we assumed class effects, that is, we deemed all second-generation antipsychotic utilization to be on-label regardless of the drugs’ specific FDA approvals. For second-generation antipsychotic prescriptions that were not associated with serious mental illness diagnoses, we assessed for other mental illness or no mental illness (see online supplement).

Because the MAX data include a maximum of two diagnoses per claim, whereas Medicare claims can have up to 25 diagnoses, our analyses included only the first two Medicare diagnoses to balance the observable information among the payers.

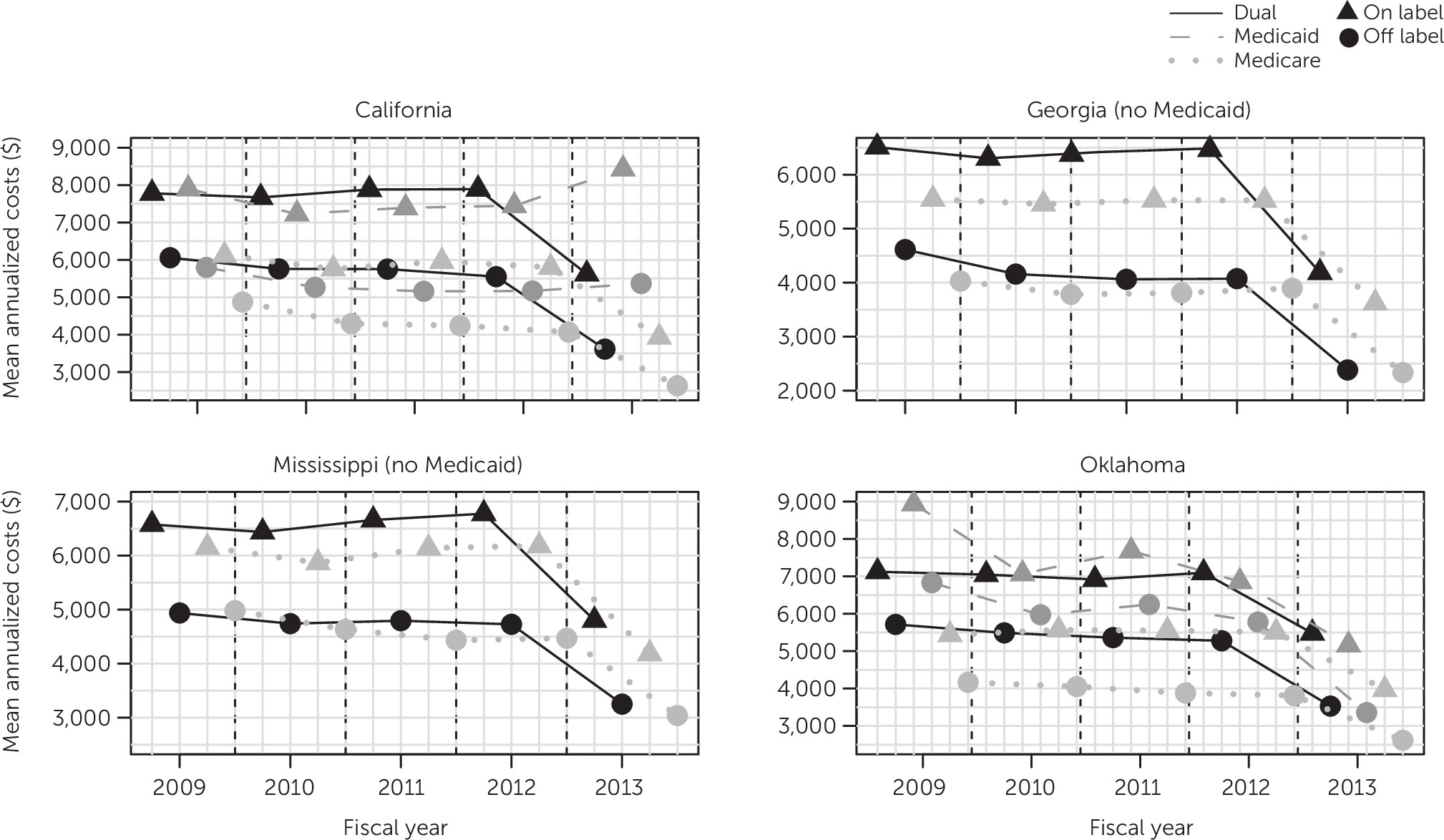

We evaluated two secondary outcomes: average monthly standardized second-generation antipsychotic dose and mean annualized second-generation antipsychotic costs. We determined standardized dose by using the defined daily dose approach (

13). For costs, given our payer perspective, we used payer-paid amounts, inclusive of low-income cost-sharing subsidy amounts for Medicare beneficiaries. We report mean inflation-adjusted, annualized costs stratified by year and payer; mean annualized costs were estimated as the average observed monthly costs multiplied by 12. We adjusted for inflation to fiscal year 2013 by using the producer price index for pharmaceutical preparation manufacturing (

14). Our costs calculations did not account for rebates and discounts received from drug manufacturers.

Covariates.

All covariates characterized the person, with some varying across person-months (see online supplement). Our main covariates were race-ethnicity and fee-for-service payer (hereafter, payer); others included age at entry into the panel, sex, neuropsychiatric morbidity frequently associated with off-label prescribing (i.e., anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cognitive disorders, mainly nondementia in this nonelderly population), and two time variables (year of panel entry, to capture cross-sectional effects, and aging, a measure of the person’s tenure in the panel at the time of second-generation antipsychotic utilization, to quantify longitudinal associations).

Given our interest in assessing the impact of race-ethnicity on likelihood of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics, analytic choices were made regarding the inclusion of variables related to beneficiaries’ socioeconomic status that may mediate those effects. Socioeconomic status variables were not included because these analyses adhere to guidance by the Institute of Medicine (

15), which calls for all racial-ethnic differences in health care utilization mediated through factors other than health status (and preferences) to be included in the estimates of disparities.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted separately by state, with second-generation antipsychotic prescription person-months as the observation unit. We estimated unadjusted rates of off-label second-generation antipsychotic utilization for person-months and persons. Because beneficiaries may receive serious mental illness diagnoses over time, we estimated person-level rates of never off-label, always off-label, and off- to on-label second-generation antipsychotic utilization. Person-level rates were reestimated after removing the assumption of class effects and reclassifying person-months according to whether the second-generation antipsychotic was approved by the FDA for the observed diagnosis. We also reestimated the rates of off-label utilization when using all the diagnosis slots in the Medicare data.

For adjusted analyses, including dose-related analyses, we used generalized estimating equations to account for repeated monthly observations assuming serial correlation with an AR(1) structure within-person, a structure that permits the present outcome value to immediately depend on the previous outcome value. For the odds of monthly off-label second-generation antipsychotic utilization, we estimated odds ratios (ORs) using a logit link and evaluated associations of the odds of off-label utilization with all covariates. Models also included interactions terms between payer and race-ethnicity. We eliminated interactions lacking statistical significance and reestimated the model, reporting results as ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (see online supplement). We report dose results as rates (with 95% CI) of average monthly standardized dose relative to the reference category. CIs were not adjusted for multiplicity of estimation. Data were analyzed with SAS, version 9.4.

Discussion

Using a conservative approach to examine patterns of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotic medications among publicly insured adults in four states and in fiscal years 2009–2013, we found that utilization was always off-label for a large fraction of users, roughly two in five, many of whom (26%–36%) had no mental illness diagnosis. Key findings were that although fee-for-service payer did not modify the relationship between race-ethnicity and off-label utilization, race-ethnicity and payer were generally associated with off-label utilization (lower for users belonging to racial-ethnic minority groups, especially Blacks relative to Whites, and higher for those having Medicaid and to a lesser extent Medicare as payers relative to dually eligible beneficiaries). We also found that although off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics increased in all states relative to the baseline year, a downward trend followed in three of the four states. Other findings were that the doses used for off-label indications were up to four-fifths the dose used for on-label indications, and average costs were at best two-thirds of those associated with on-label utilization.

Although off-label prescribing has a long tradition in medicine, and may be appropriate in some cases, the decision to prescribe medications off-label should be made with careful consideration of the potential risks when the evidence of benefit is minimal or mixed (

16). A 2011 review of the evidence on off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics concluded that selected drugs may be associated with small benefits in the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or dementia (

6). However, adverse events, including cardiovascular morbidity, were common, despite observation periods that were far shorter than the longer exposures typical of routine care (

6). A recent evidence review concluded that off-label prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics is inappropriate because the risks of such prescribing outweigh potential benefits that are uncertain and at most minimal (

17). The practice has a particularly unfavorable risk-benefit profile for individuals who are Black or Latino. Not only do Black adults have a higher risk for cardiometabolic disorders than Whites (

18,

19), which, with some exceptions, is also the case for Latinos (

20,

21), but Black race appears to confer a higher risk for weight gain related to use of second-generation antipsychotics (

22). The evidence is less clear for other cardiometabolic effects (

23).

Off-label utilization has economic implications for the payers. Until well into our study period, antipsychotics were the costliest drug class for Medicaid; by 2009, these costs were almost double those of the second costliest class among fee-for-service beneficiaries (

24). The Medicare prescription drug plans that manage Medicare’s Part D benefit on behalf of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (

25) are also large purchasers of second-generation antipsychotics (

26). Although costs of second-generation antipsychotics have dropped after generic products entered the market, they remain expensive to payers (

27). Thus, public payers bear a large portion of the economic consequences of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics, and they are also likely to be the payers for care associated with cardiometabolic morbidity related to second-generation antipsychotics use.

In our study, Blacks in all states and Latinos in two states, including California, where they made up one-fifth of the study population, had lower off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics than did Whites. Although our finding might stem from prescribers’ efforts to minimize risks, alternatively, it may have resulted from provider and system factors that underlie widely documented racial-ethnic disparities in health care (

15,

28). This explanation is supported by evidence that prescribers have limited knowledge of approved indications, including approved indications for second-generation antipsychotics (

29).

Our finding of differences among payers in off-label utilization is novel, because little evidence for such differences currently exists. Medicaid and Medicare employ utilization management strategies such as previous authorization to steer care toward lower-cost drugs (

30,

31). However, the programs vary in their use of these strategies to shape utilization; they also vary in their approaches to negotiate lower prices and the size of the rebates (

32) and in their adoption of value-based payment models over the past decade (

33). The absence of substantive differences between data for Medicare beneficiaries and dually eligible beneficiaries may be due to the federal government’s regulation of the pharmacy benefit for both. Prescription drug plans have latitude in their implementation of utilization management (

30) and tend to use previous authorization to manage utilization of second-generation antipsychotics. Medicaid beneficiaries’ higher off-label utilization may stem from Medicaid programs’ preference for not employing aggressive antipsychotic utilization management for adults (

30,

34). Specifically, the Medicaid states in our study (California and Oklahoma) have implemented only modest diagnosis-related restrictions to adults’ access to second-generation antipsychotics (

35,

36).

The drivers of the general downward temporal trend that followed an initial surge in the likelihood of off-label utilization in three of the four study states are likely multifactorial but may include concerns about the health or economic implications of the practice. Our dose findings are noteworthy because no systematic evidence exists to guide dosing for off-label indications. Moreover, because of limitations in the evidence on dose dependence of cardiometabolic effects of second-generation antipsychotics among people with serious mental illnesses (

37,

38), the use of lower doses for off-label users may be less protective than prescribers might believe.

Our finding of substantial cost reductions in fiscal year 2013 for most states and payers was not the result of reductions in doses of second-generation antipsychotics; our analyses showed that doses were quite stable throughout the study period (results not shown). A potential explanation is savings resulting from the entry in late 2011 of generic olanzapine and in early 2012 of quetiapine and ziprasidone, all three of which are widely used second-generation antipsychotics.

We cannot draw firm comparisons between our results and those in the available literature. Published rates of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics among adults have varied widely, ranging between 17% and 85% (

4,

17,

39–

42), probably as a result of differences in populations, study years, and study methods. The limited evidence on the association between race-ethnicity and off-label utilization is mixed, and no study has assessed the modifying effect of payer (

40,

43). We are aware of only two survey-based studies that reported on variation of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics and associated costs by payer (

42,

44), but the only study conducted after Medicare Part D was implemented based its conclusions on analyses of aggregate visits (

42). Few studies have reported on temporal trends (

43), and we are not aware of recent evidence. Our finding that off-label doses are modestly smaller than on-label doses is consistent with limited previous research (

41).

Our study had some limitations. First, because treatment-resistant major depressive disorder requires an assessment of failure of antidepressant monotherapy, a complex undertaking when using administrative data, we required only evidence of illness severity. This decision and our assumption of class effects may have led to underestimation of the true prevalence of off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics. Our decision to restrict our analysis to two diagnostic codes for person-months covered by Medicare or dual payers to avoid ascertainment bias may have had the opposite effect, although the decrease in always off-label utilization was minor. Underdocumentation of serious mental illness diagnoses might also contribute to overestimating off-label utilization. However, there is substantial agreement of claims-based serious mental illness diagnoses with diagnoses based on more clinically rich sources (

45,

46), and it is unlikely that underdocumentation differed systematically among payers. Second, we may not have fully controlled for differences in case mix among the payers. However, if we assume that all off-label uses of second-generation antipsychotics are of equal low value, such differences should not affect our conclusions.

Third, our study may not be generalizable to other states, nor is it generalizable to off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics under managed-care arrangements, which might make greater use of utilization management strategies. Fourth, because we lacked information on prescriber discipline or specialty, we were unable to assess its association with off-label prescribing, particularly in the absence of a mental illness diagnosis. However, some evidence suggests that although psychiatrists may be more likely to prescribe antipsychotics off-label (

42), nonpsychiatrists appear to be far more likely to prescribe antipsychotics without documenting a mental illness diagnosis (

5). Fifth, given the years covered by our analyses, they may not reflect current patterns of off-label utilization among publicly insured fee-for-service beneficiaries that may have been influenced by changes in costs of second-generation antipsychotics or quality measurement initiatives launched as part of the Affordable Care Act and the move toward value-based payment models. Although additional generic drugs have entered the market in recent years, entry of generic drugs does not necessarily translate to marked cost reductions for payers, and any cost reductions may have been offset by the entry in 2015 of two new second-generation antipsychotics. We are unaware of any performance measurement system broadly used by public payers that monitors off-label utilization of second-generation antipsychotics. Last, we overestimated the costs to the payers, more so for Medicaid, because like others (

47), we did not account for rebates and discounts. Nevertheless, our cost findings are meant to provide only a signal of the significance of off-label utilization for the payers.