Suicide, the second leading cause of death among youths and the 10th leading cause of death among all age groups in the United States, claims over 40,000 lives annually (

1). From 1999 to 2017, the average age-adjusted suicide death rate increased from 10.5 to 14.0 per 100,000 population in almost all U.S. states. In 2017, suicide resulted in the loss of approximately 47,000 lives (

2). National efforts addressing these detrimental events, including the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, Safety Planning Intervention, Zero Suicide campaign, and National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, have focused on multifaceted interventions in health care settings, including identification of warning signs for suicidal crisis, ongoing physician education for evolving suicide prevention practices, comprehensive assessment and management of suicidal patients, community outreach, and hotlines (

3).

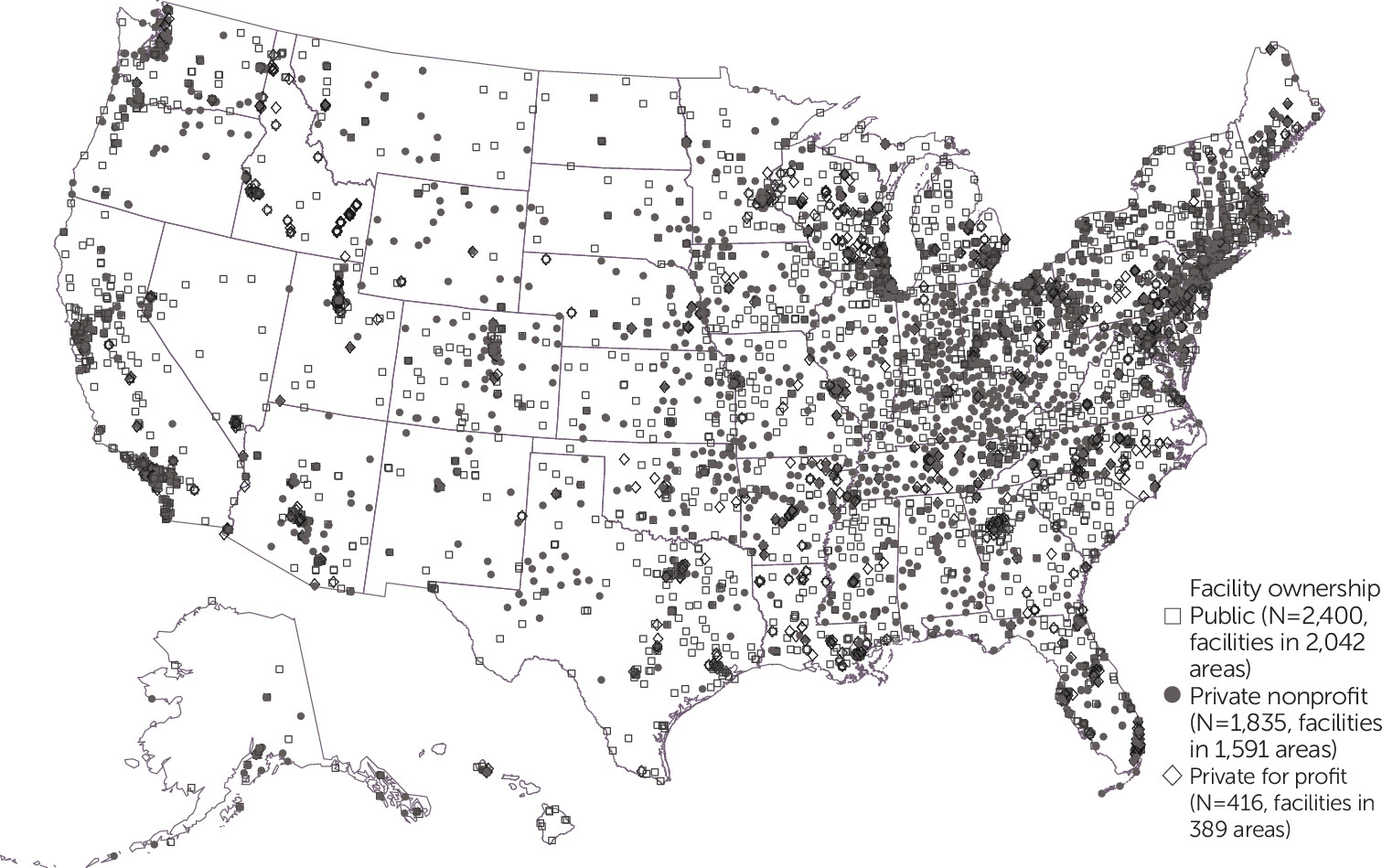

Historically, private for-profit health care facilities were less likely than public and nonprofit facilities to provide unprofitable services, such as psychiatric emergency services, trauma care, and assertive community treatment programs (

14,

15). Literature suggests that public and nonprofit organizations usually deviate from profit maximization behavior (

16). Therefore, we would expect public and private nonprofit facilities to be more likely than private for-profit facilities to offer suicide prevention programs.

Maldistribution of mental health services by facility ownership might result in some markets having more services and others not enough. A vivid example is rural America, where residents face disproportionate difficulties in accessing mental health providers. As of December 2020, over 58% of areas with shortages of mental health professional were in rural communities (

17). Yet, evidence regarding the association between rural versus urban residence and use of specialized mental health services is mixed (

18–

20). For instance, veterans in rural areas were less likely to receive treatment in OMHC facilities, compared with their urban counterparts (20% versus 33%) (

18). However, other studies found similar rates of receipt of mental health services among urban and rural adults with major depressive episodes or any mental illness in the past year. Because rural residents (youths and adults) have been found to be more likely to have serious thoughts of suicide in the past year (

21), examining whether rural and urban OMHC facilities provide suicide prevention programs is essential.

Little is known about the availability of suicide prevention programs in outpatient settings. In this retrospective study, we examined the availability of such programs in OMHC facilities across the United States and whether facility ownership and rurality were associated with the provision of these programs.

Discussion

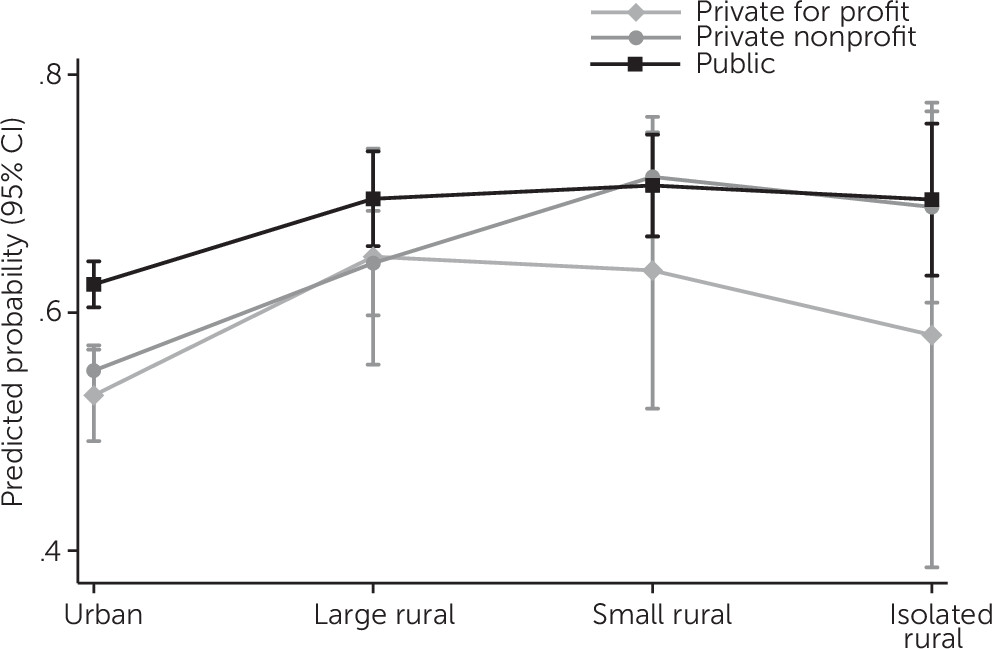

This study showed that less than two-thirds of OMHC facilities offered specialized suicide prevention programs in 2019. Despite nationwide increases in suicide, a lack of uniformity exists in the provision of these programs, which varied by facility ownership and payment acceptance. Most communities relied on public OMHC facilities to offer suicide prevention programs. Private for-profit facilities in isolated rural areas were less likely than their less rural counterparts to provide suicide prevention programs. In contrast, private nonprofit facilities had a higher probability of offering these services as the locations of the facilities increased in rurality.

Specialized suicide prevention programs may offer services tailored to address the needs of patients at risk of suicide (

9). Evidence shows that around one-fourth of suicide decedents had contact with outpatient mental health services during the year before death (

9). These missed opportunities to help suicidal patients while they struggled and sought help occurred while suicide mortality was increasing nationwide (

1). Professionals trained in best practices to identify suicide risk factors; provide appropriate evidence-based practices; and understand the diverse interplay between psychological, social, environmental, and cultural predictors are integral to reducing suicide in the United States (

27,

28). Specialized suicide prevention programs in OMHC facilities may help professionals more regularly receive training to detect risk and administer assessments, interventions, and appropriate management of patients contemplating suicide.

Provision of suicide prevention programs differed by ownership status. Nearly 66% of public facilities and half of private for-profit facilities offered suicide prevention programs. These findings are pertinent, given the national call for Zero Suicide initiatives. In 2010, the Joint Commission and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention initiatives to catalyze inpatient and outpatient mental health services to better treat patients with suicidal behaviors (

17,

29). The lack of uniformity in the provision of outpatient suicide prevention programs, however, may hinder nationwide efforts to achieve the goal of zero suicides. Evidence-based treatments for suicidality have emphasized the importance of outpatient mental health treatments using suicide-specific intensive psychological care, which helps replace or eliminate suicidal thoughts (

27,

28). Yet, as our data showed, this care is not universally available in OMHC facilities.

All facilities, across all ownership types, must balance costs and revenue to continue offering services. To provide SAMHSA-defined suicide prevention programs, a facility must screen all patients for suicidal ideation, review each patient’s suicide risk factors, continually educate professionals, establish a collaborative treatment process with all stakeholders involved, engage all stakeholders in regular follow-up, have capacity to store psychotropic medication, provide educational modules, and offer patient hotlines (

13). These tasks sound arduous, but suicidal patients’ needs may change rapidly and without warning. The ability to provide such intensive care may ultimately depend on costs associated with length of services, care transitions for each facility, and prices that facilities can charge based on patients’ insurance status.

Suicidal patients are particularly susceptible to financial strain and more likely to experience financial distress than many other patient groups (

30). The out-of-pocket costs for mental health treatments might impede access to necessary intensive services for this vulnerable group. These socioeconomic realities, combined with our findings that facilities serving uninsured and Medicaid patients are less likely to offer suicide prevention programs, should prompt urgent policy changes. These results suggest the need for an improved payment scheme to better support ongoing suicide prevention initiatives at all types of facilities, especially those accepting patients who are uninsured or enrolled in Medicaid. Barriers to accessing specialized professionals with adequate skills and ongoing training to reinforce suicide prevention initiatives may leave suicidal patients without immediate access to needed services. Having suicidal thoughts is painful. Financial barriers to care from specialized professionals can be disastrous.

It is encouraging that rural nonprofit OMHC facilities were more likely than urban facilities to offer suicide prevention programs, given the higher suicide rates, greater access to lethal means, and limited mental health specialists and other emergency health care facilities in rural communities (

31). Greater access to lethal means and the lack of health care providers make individuals in isolated rural areas vulnerable to suicide. However, private for-profit facilities in isolated rural areas were found to be less likely than those in less rural areas to adopt suicide prevention programs, after the analysis controlled for age, sex, race, and state location, which is striking, given that suicide rates in isolated rural areas are the highest and have been increasing the most rapidly across all rural counties since 1999 (

32). Residents in rural communities often are affected by a lack of access to health care in general. These isolated rural communities have fewer mental health care facilities, compared with larger, urbanized rural areas. The fact that the OMHC settings in isolated rural areas were less likely to provide suicide prevention programs may have exacerbated lack of access to care and other suicide-related issues.

Many nationwide suicide prevention services, such as those provided by the VA and U.S. Department of Defense, are in the public sector (

33). Introduced in 2015, the Prioritizing Veterans Access to Mental Health Care Act acknowledged the increase in suicide attempts and deaths by suicide among veterans (

32). However, access to mental health care should be ensured for all military personnel and civilians across public and private sectors nationwide, because suicide rates have been increasing across all groups. Federal and state legislation can address the lack of suicide prevention programs across all OMHC settings, encourage the provision of specialized suicide prevention programs, and authorize programs to advance professional training for suicide prevention. For example, the Joint Commission’s 2019 National Patient Safety Goal added suicidal ideation screening for all patients, use of evidence-based processes for suicide risk assessment, written monitoring and care procedures to mitigate suicidal ideation, and treatment and follow-up care for patients at risk of suicide as new requirements for its behavioral health care accreditation programs (

17). These requirements may strengthen mental health treatment programs by offering suicide prevention for all patients. However, offering suicide prevention programs is not universally required in the current mental health facility licensures; the weak regulations to ensure the universal provision of such programs in mental health facilities might have contributed to disparate availability of suicide prevention programs.

State Medicaid policies may influence the availability of outpatient suicide prevention programs; our data indicated that facilities accepting uninsured or Medicaid patients were less likely than those not accepting these patients to offer suicide prevention programs. Although uninsured patients often face difficulties obtaining health care (

34), our data indicated that even if they were able to access an OMHC setting, suicide prevention programs were often unavailable in those settings. Unfortunately, OMHC facilities that accepted Medicaid did not always have suicide prevention programs available for these patients. This finding suggests that the adequacy of suicide prevention networks should be addressed in all Medicaid plans. Medicaid expansion might not suffice to ensure access to suicide prevention programs. The stability of reliable payments for specialized suicide prevention programs may contribute to financial viability for OMHC facilities, whereas the potential risk of providing intensive services to uninsured patients or Medicaid enrollees with low copayments may worsen the financial vulnerability of such services.

This study had several limitations. First, we used the most up-to-date data available (2019) in the SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. However, it is not yet clear how many facilities will provide specialized suicide prevention programs in the years ahead. Other forms of suicide prevention care, such as hotline help and informal follow-up calls, may not qualify as suicide prevention programs per SAMHSA’s definition. Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence regarding the benefits of suicide prevention programs. Second, this national database is updated continually, which allowed us to identify service provision variability as a simple dichotomous variable measuring whether suicide prevention programs were offered but not how they were offered. Data on the capacity and scope of suicide prevention program services for each facility were unavailable. It is possible that private for-profit facilities were larger and served patients across ZCTA boundaries. However, the greater the number of suicidal patients served by private for-profit facilities, assuming the patients are randomly distributed across all private for-profit facilities, the less likely it is that these patients will receive specialized suicide prevention programs. Finally, our analysis focused on OMHC facilities. The distribution of suicide prevention programs by ownership may be different in other settings, such as inpatient mental health treatment facilities, general health care facilities, and community health centers. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the interplay of cultural, social, and clinical barriers with the provision of outpatient suicide prevention programs in various health care settings. This information will allow further research to identify effective measures to address barriers to the provision of suicide prevention programs across public and private mental health facilities.