With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, many countries imposed stringent measures to mitigate transmission of the disease. These mitigation measures had substantial economic and social ramifications, with millions of people losing their jobs worldwide and experiencing substantial levels of social isolation for weeks or months. These policies have affected clinical care for most patients with chronic conditions requiring regular care. Much of the focus to date has been on the direct impact of COVID-19, with limited attention to the impact of the reduced social interactions and mitigation efforts on patients (i.e., the indirect effects of the pandemic).

Patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) are generally young and, although high obesity rates have been reported at this stage (

1), may not yet have many of the medical comorbid conditions (e.g., obesity, hypertension, or diabetes) frequently present among patients with multiple episodes and that increase the risk for severe COVID-19 disease (

2,

3). Nonetheless, the initial period after a psychotic episode is critical because several clinical trials have indicated that early intervention has the potential to improve long-term outcomes (

4). Restoring functional capacity is a primary goal in this process, with treatments designed to set and achieve employment and educational goals (e.g., individual placement and support as a key component of coordinated specialty care approaches) (

4,

5). Moreover, it has been reported that at the initial stages of these conditions, the risk for suicide is greater than at later stages, which could be magnified during the pandemic (

6).

During the pandemic, continuation of recovery-oriented treatments has been challenging (

7). COVID-19 mitigation efforts have had large and divergent effects on the economy. Many industries have been adversely affected, leading to job losses or furloughs of millions of their employees, whereas other industries have prospered as the patterns of commerce and social interaction have shifted. Patients with FEP might be at a disproportionately high risk for job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic because of the industries in which many work, recency of their job tenures, and more subtle factors related to stigma (

8). Moreover, the pandemic has disrupted education worldwide, which may exacerbate well-documented opportunity gaps that put students needing accommodations at a disadvantage relative to their peers (

9).

Currently, little information is available regarding the pandemic’s impact on employment, education, or suicide rates in the FEP population (

10). Given that early intervention in this population has the potential of yielding a magnified benefit, and that timely return to education and employment may delay or prevent disability (

11,

12), it is particularly important to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FEP care to rapidly adapt care delivery to optimize outcomes in this population during this global crisis. In this study, we sought to examine the potential effects of the pandemic by examining electronic health records (EHRs) for a cohort of patients receiving care in a large early psychosis clinic in the United States.

Methods

We used data from EHRs to identify all active patients as of March 24, 2020, receiving care at McLean OnTrack, which is McLean Hospital’s subspecialty FEP clinic (

13) (for full details of the data extraction process, see an

online supplement to this article). Briefly, we extracted baseline information from intake and clinical and functional information from subsequent notes available at each physician encounter. We selected information available from January 1 to September 21, 2019, and from January 1 to September 21, 2020, including employment and educational statuses at the time of each mental health visit. We classified employment status into one of five mutually exclusive categories: full-time employment, part-time employment, unpaid internship, reduced work hours or furloughed because of COVID-19, and unemployed. Similarly, we used four classifications of educational status: full-time student, part-time student, leave of absence, and out of school (including on summer break). This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board. We obtained written individual waivers of informed consent from the study participants.

We classified patients as having COVID-19 if they had a positive reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result after nasopharyngeal swabs, in accordance with the guidelines established by the World Health Organization. At the time of the study, patients did not routinely receive antigen or antibody testing. We determined deaths using Massachusetts death certificate data linked with the EHR data. This data set is provisional because it contains information on deaths up to the past week and adjudicated causes of death by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; it also contains records that have not completed the adjudication process.

Mitigation Efforts

Massachusetts implemented a progressive series of policies aimed at mitigating disease spread (

14). For example, on March 24, 2020, the state implemented a stay-at-home order through July 6, 2020. Most colleges transitioned to remote learning before or around March 23, 2020, that extended to the end of the academic year (

15). McLean Hospital implemented work-from-home policies for nonessential work on March 16, 2020; furthermore, the McLean outpatient clinic, where McLean OnTrack is housed, transitioned to full telehealth care by March 20, 2020. A master’s-level supported employment and education (SEE) specialist offered consultations to the patient or clinician as needed; in addition, all patients had access to weekly vocational and college groups that were led by a certified employment support professional and certified peer specialist. After the transition, all SEE activities and groups were converted to a virtual format along with all other clinical care. No changes in the philosophy and goals of the SEE delivery were made after the start of the pandemic.

Over the summer, the state introduced a phased plan in which local areas could begin to lift the mitigation policies as they met disease control targets. By September 21, 2020 (i.e., at the end of the study observation period), 39 of the 54 cities and towns in Massachusetts (72%) had met the criteria to enter phase III, stage II (i.e., the reopening that extends to indoor and outdoor recreation businesses and outside gatherings of up to 100 people) (

16).

Statistical Analysis

In the main analyses, we dichotomized our outcomes (e.g., employed vs. not employed); we then plotted over time the percentage of the cohort that remained employed or actively engaged in formal education. To illustrate the state-level employment changes, we plotted the percentage of the statewide workforce that was employed in each calendar week during the same weeks of 2020. This measure was defined as the number of individuals without unemployment claims filed in the state, weighted according to the educational attainment of the cohort. The number of individuals without unemployment claims came from the total labor force at that level of educational attainment (per the American Community Survey 2019 estimates) (

17) minus the number of unemployment continuing claims in a given week. The denominator was the labor force at that level of education.

We examined changes in employment and education relative to state emergency policy implementation dates. To examine changes in employment, we estimated changes in the average weekly employment proportions in the weeks before March 24 versus the weeks after March 24 (i.e., the stay-at-home date in 2020). Similarly, to examine changes in education, we estimated changes in formal educational involvement in the weeks before and after March 16, 2020. Because formal education and several types of employment can have seasonal patterns, we compared these changes with the average changes in the weekly employment proportion experienced by the same open cohort before and after the same time points during the year 2019.

We used a generalized linear model with a Gaussian distribution and robust standard errors in which the effect of the stay-at-home order was assessed by an interaction term between an indicator of week after the stay-at-home date to account for both measured and unmeasured time-stable differences between the groups (

18). Patients who were lost to follow-up (i.e., did not reach September 21, 2020, enrolled in our cohort) contributed information only during the weeks they remained enrolled.

We conducted several prespecified stratified and sensitivity analyses. First, we stratified our results according to gender, age range at the index date (<21, 21–30, >30 years), bipolar disorder diagnosis, and substance use disorder diagnosis. Because we also considered that the indirect effects of the pandemic would be different in magnitude according to the self-reported race at baseline, we stratified our analysis within levels of this variable. Sample sizes precluded any specific race comparison, and hence we grouped all the non-White self-reported races in order to gain a larger sample size for the comparison group. Second, to assess the potential impact of differential attrition, we used inverse probability weighting (

19). Third, we examined dates when no policies were instituted in falsification tests (see the

online supplement). Finally, to observe gradual effects over time (as opposed to changes in averages), we repeated the analyses including an interaction term between the effects of the policy and time. We used R statistical software, version 3.5.2, for all analyses.

Results

Our cohort had 128 patients, with a mean±SD age of 22.4±3.8 years. Of these patients, 23% (N=30) were female, 46% (N=59) had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and the remainder had a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. A total of 99 patients self-reported as being White (77%), 10 Black (8%), and 12 Asian (9%); two (2%) reported being of other race. The sample sizes precluded specific race comparison. We grouped non-Whites in order to gain a larger sample size for the comparison group. Because we considered that the indirect effects of the pandemic would differ in magnitude according to the self-reported race at baseline, we stratified our analysis within levels of that variable by using White and non-White as our grouping variable.

Table 1 displays other baseline characteristics. Overall, 80 (63%) of the patients were actively involved in treatment by January 1, 2019, and provided a median of 32.7 months (interquartile range [IQR]=17.5–51.4) of data. The remaining 48 patients (38%) entered the cohort between January 1, 2019, and March 24, 2020. Two patients (2%) were enrolled in 2020. Patients contributed information for a median of 77 weeks (IQR=63.0–88.0).

Through the end of the follow-up period, 12 patients (9%) from our cohort had any RT-PCR test for COVID-19. Nine patients were tested once, two were tested twice, and one was tested three times. All test results were negative. No deaths occurred in our cohort during the study period for any reason, including suicide. The median interval between two consecutive visits with a psychiatrist was 31.5 days (IQR=26.5–53.1) in the period before the stay-at-home orders, and it was 24.5 days (IQR=15.0–33.0) in the period following them. Only five patients (4%) disenrolled from our cohort after transition to telemedicine.

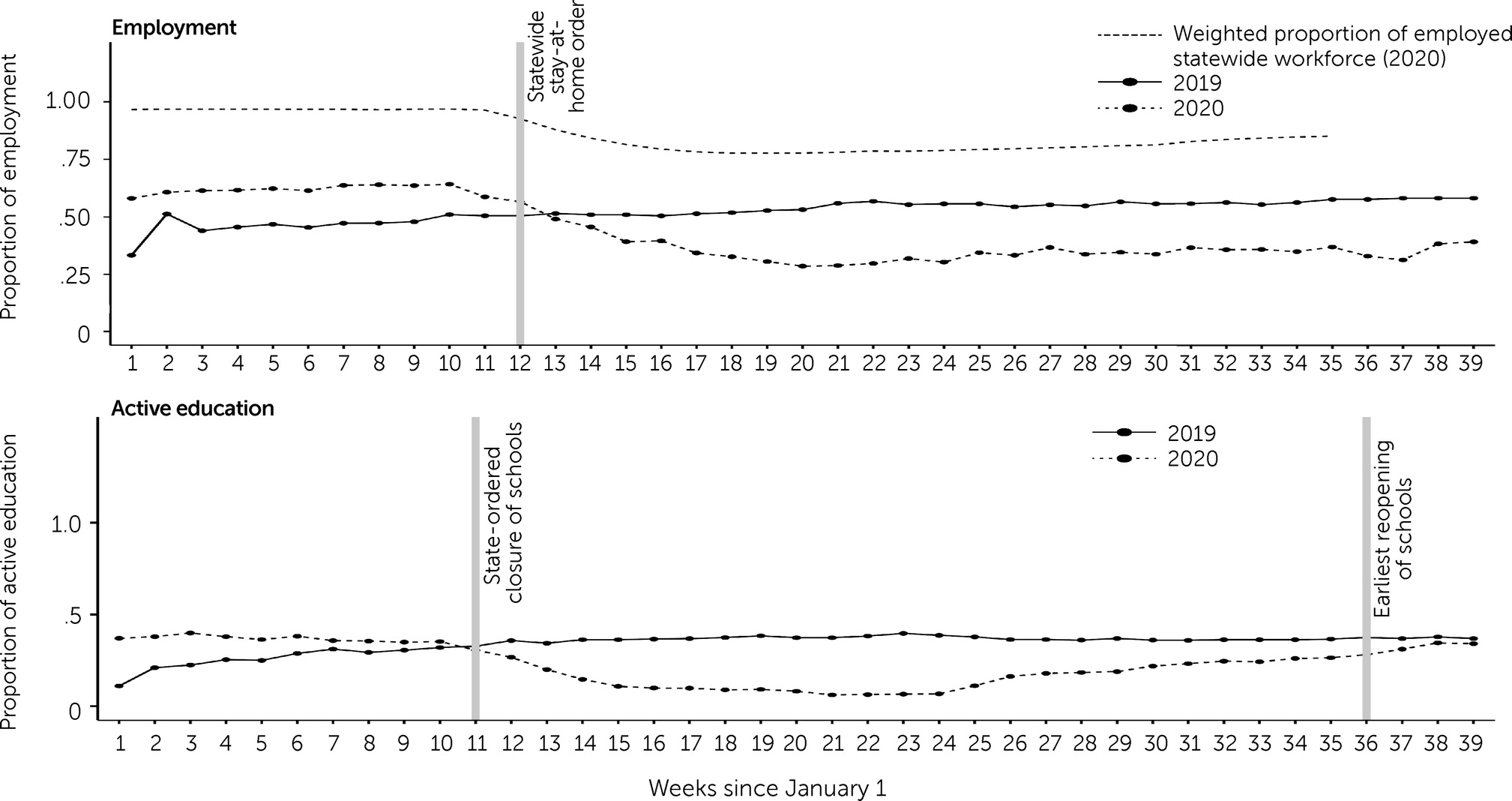

Unemployment claims filed in the state of Massachusetts increased rapidly after the stay-at-home orders. In the week before the enforcement of the policy (e.g., the week of March 7, 2020), only 3% of the total workforce in the state had filed at least one unemployment claim. That proportion reached a maximum by the week of May 17, 2020, extending to 22% of the workforce. However, after that week, the proportion of the workforce filing unemployment claims started to decrease gradually, reaching 15% by the end of the evaluated period, in the week of August 29, 2020. Employment losses among patients with FEP were greater and more rapid than among the general population (

Figure 1).

For example, in the week of March 7, 2020, 41% (N=52) of our cohort were unemployed, reaching 71% (N=91, a maximum during the observation period) in the week of May 17, 2020. After that week, the percentage of patients who were unemployed decreased, reaching a minimum of 61% (N=78) in the last week with available data (September 21, 2020) (

Figure 1). In 2020, average employment after the stay-at-home order was instituted was 33% (95% confidence interval [CI]=30%–37%) lower than before the order, compared with the change during the same period in 2019. As the pandemic progressed, employment recovered in the general population to a much greater extent than among patients with FEP.

Male patients were more likely to lose their job than were female patients, as were patients ages <21 years or >30 years, compared with patients between ages 21 and 30. Furthermore, patients with a documented history of substance use disorder were more likely to lose their job than those without a substance use disorder. Finally, patients with an incomplete high school education, who did not identify as White, and without an affective disorder diagnosis had greater losses of employment compared with their respective counterparts (

Table 2).

Similarly, the proportion of patients actively engaged in a formal education program dropped substantially in the early stages of the pandemic (

Figure 1). Although educational engagement recovered in the fall of 2020, it still remained below the 2019 levels. Our model showed that in 2020, average active educational engagement after the stay-at-home order was instituted, on average, was an additional 29% (95% CI=23%–34%) lower than before the orders in the same year, compared with changes during the same period in 2019. The average proportion of patients in active education was 37% (N=47) during the week of September 21, 2019, and 34% (N=43) during the same week of 2020. Increases in employment were limited as communities relaxed their mitigation efforts, but increases in educational engagement were larger over time (see

online supplement). Results were robust to sensitivity analyses (see the

online supplement).

Discussion

In this cohort of patients with FEP, we observed major job losses and educational disruption during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts. The job losses in the population with FEP exceeded those in the general population by several fold. By mid-September, nearly 6 months after the imposition of lockdown measures in Massachusetts, the relative rate of formal employment and engagement with educational programs had decreased by about 30%. We found only limited levels of recovery in employment in our cohort, although the percentage of patients engaged with an education program approached prepandemic levels by that time.

Our findings are consistent with those of studies that have shown that disasters have a greater impact on those who were more vulnerable before the disaster occurred, such as workers working low-wage jobs and from minority groups (

20). Although our study was not adequately powered to investigate this association, we also found a disproportionate effect among those who self-reported belonging to racial-ethnic minority groups, in keeping with numerous reports on the effects of disasters on racial-ethnic minority groups (

21). In our sample, the disruptions in care or other shocks after psychosis onset could have substantial impact on later trajectories, compared with similar shocks occurring later in the disease course (

22). The timing and duration of disruptions in FEP care have been examined in the context of initiation of care (i.e., reduction in the duration of untreated psychosis) (

23) and timing of specialty care termination (

24). In each case, clear and substantial impacts on long-term outcomes can be observed as disruptions approach the 1-year mark. As the ongoing disruption to the lives of FEP individuals from the pandemic mitigation efforts approaches this timescale, these patients may be at risk for long-term repercussions (

25).

Supported employment and education has been one of the most successful approaches to facilitating return to competitive jobs and to improving long-term outcomes and treatment engagement (

4,

5). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused major reductions in employment status and education disruption among patients with FEP. Importantly, the employment and educational interruptions could mediate the well-replicated finding of more suicides occurring after previous pandemics, although we did not observe any suicides during the observation period (

26). However, this latter result should be taken with caution because examining suicidal ideation or suicide attempts was outside the scope of this project.

Moreover, although the number of patients who reengaged in formal education approached baseline levels, we used a very generous definition of educational engagement that did not attempt to assess the quality of the education. Within the broader population and among those with special educational needs, numerous reports have raised concerns about decrements in educational quality during the pandemic. In this sense, the pandemic might exacerbate issues that these patients already face, such as stigma, isolation, marginalization, and deterioration of social networks (

27). Furthermore, the employment shocks themselves lead to more clinical events, including hospitalizations (

28).

In an earlier analysis of the same cohort of patients with early psychosis (

29), we observed significant worsening of patients’ symptomatic status as well as a higher severity in the presentation of patients who came to the emergency department because of psychiatric problems in the early weeks after the transition to telemedicine. This finding supports a role for the effects of self-isolation and the stress induced by the pandemic, as reported elsewhere (

30), as well as the clinical effects that employment loss would directly cause.

Finally, the long-term repercussions of job losses and educational disruption are still to be determined. In a prepandemic analysis of patients from the same clinic, we noted relatively encouraging outcomes regarding returning to college, with 56% of the patients returning to college after a median of 18 months of treatment (

31). Concerning employment, in an analysis conducted in Finland among patients with FEP, only 14% of the sample had gained full employment by 12 months, compared with 65%–69% in the control sample (

32). In the current context, however, patients with FEP are experiencing even more barriers than they usually face in the area of work and education; moreover, the systems available to provide support (such as FEP clinics) are also navigating large shifts in how care and support are being delivered. As the duration of time without employment or being engaged in education increases, the probability of reentry for this population also might be reduced. In other words, although the pandemic might be inducing acute and transient changes to the clinical care of most patients with chronic conditions, the long-lasting impact of these shocks on the long-term outcomes of patients with early psychosis remains to be determined.

This study had important strengths. We could follow a relatively large cohort of patients with FEP prospectively and extract detailed information at each clinical visit, which typically occurred weekly at first and then monthly or less frequently depending on clinical status. Hence, we were able to extract granular information on educational and employment status to detect changes in trajectories that would occur in relatively short time frames. Clinicians usually report these parameters as part of their routine evaluation at the clinic (

31). Finally, the high levels of retention allowed us to use the same weeks in the previous year among the cohort for comparison purposes and to remove seasonal trends or other external shocks explaining our findings.

The study also had several limitations. First, we were unable to capture the type of employment before and after the pandemic, hours worked, or income levels. Second, our employment and education status information was based on a self-report from the patient to the clinician during routine visits; therefore, it could reflect reporting errors. In future studies, researchers should validate our findings using different data sources as well as better differentiate the time requirements from the amount of compensation (for work) or from academic degree objectives (for education).

Third, our before-after methodological approach relied on the stability of outcomes before the pandemic onset (i.e., the parallel trend assumption); in other words, the weeks in 2019 served as a proxy for the counterfactual evolution of employment and education status in 2020, had the pandemic not occurred (

18). This approach may have underestimated the true employment and educational effects had the cohort improved over time with treatment; likewise, it could have overestimated the true effects had the cohort worsened over time with disease progression. We did not observe any such positive or negative trends during the 15 months preceding the mitigation efforts.

Fourth, our sample might not have been representative of the entire national population of people with FEP receiving care at coordinated specialty care clinics, as evidenced by a high proportion of college graduates and patients reporting White race (

13). In part because of the potentially favorable distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of this study cohort, we suggest that our results reflect a conservative estimate of the adverse pandemic effects on patients with FEP. Stated differently, the adverse pandemic impact on employment and education could be worse in other populations with FEP across the country. Future work will need to use larger sample sizes that include multiple FEP clinics across a large geographic area to examine potential vulnerabilities in employment and education that are related to intersecting identities (e.g., race, gender, and class). In addition, the clinic in this study included patients with either nonaffective or affective psychosis, and the inclusion of patients with affective disorders also could be associated with more favorable levels of education and employment levels. Nevertheless, sensitivity analyses restricting the sample to only those with nonaffective disease did not alter the findings.

Finally, to our knowledge, unlike for employment no standardized state-level estimates of educational engagement over time exist. In Massachusetts, public high schools and colleges resumed classes in the fall of 2020 by using a mixture of remote and in-person lessons. There have been anecdotal reports of increased truancy in some school systems and concerns about the quality of the educational process given the need for strong Internet connections to support remote learning and the novelty of the format for many. Indeed, such reports suggest that maintaining educational involvement represents only a basic step and that patients with FEP would benefit from support in navigating and prospering under the educational changes.