Major depressive episode and serious psychological distress are highly prevalent among adults (

1–

4). Severe mental illness, although less prevalent, places an immense burden on quality of life (

5). However, mental health treatment use for these conditions among adults has remained unchanged during the past two decades (

6) and is differentially distributed by race-ethnicity (

7). Black and Hispanic people are less likely to receive treatment than White people for major depressive disorder (

8), serious psychological distress (

9), and severe mental illness (

10). Data on trends through 2012 have indicated that the disparity between White and Black, Hispanic, and Asian people increased or remained unchanged during the early part of the 21st century (

11), but little is known about national trends after 2012 (

11).

Understanding trends in treatment disparities during the past decade has become more urgent, because care access has changed because of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (

12). The ACA expanded Medicaid access and increased mental health treatment coverage by marketplace private insurance plans (

13). However, this coverage may not have increased mental health treatment uptake or reduced racial-ethnic disparities (

14). Prior studies (

4,

11,

15) have used data collected before or shortly after ACA implementation; therefore, an up-to-date investigation of trends in mental health treatment disparities is warranted.

There are several other reasons for updating prior work. Although previous studies (

4,

16) have reported trends in mental health treatment disparities among the general population, these overall rates have prevented accurate assessment of gaps in treatment access among those exhibiting clinical need, because they conflate trends in disorder prevalence with trends in treatment use. Moreover, some prior studies (

15,

16) have been limited in the assessment of trends within smaller ethnic groups. The scant literature (

17,

18) on Asian people suggests that they are less likely to receive treatment from specialty mental health care providers than are White people. Moreover, American Indian/Alaska Native people continue to experience systemic barriers to mental health treatment, such as lack of health insurance and of culturally competent providers (

19), but this population has often been underrepresented in studies of mental health and mental health care (

20). Thus, there is an urgent need to evaluate mental health treatment use among these marginalized and underserved groups by using more recent and nationally representative data.

In the current study, we assessed and compared trends in racial-ethnic disparities in mental health treatment use among White (reference); Asian/other Pacific Islander (PI)/Native Hawaiian (HI); Black/African American (AA); Hispanic; multiracial; or American Indian/Alaska Native people by using 2005–2019 nationally representative survey data of U.S. adults. We focused our analysis on people who received treatment for a major depressive episode, serious psychological distress, or serious mental illness (defined as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment) during the past year. Our goal was to uncover racial-ethnic inequity in the health care system by quantifying disparities in mental health treatment use between White people, who often have better access to health care resources because of their racial-ethnic status (

21), and individuals from marginalized groups. Therefore, we selected White race-ethnicity as the reference group throughout this study.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are available in Tables S1–S3 of the online supplement to this article. In brief, public insurance access increased across all groups, except for Black/AA adults experiencing serious mental illness and for American Indian/Alaska Native adults. However, full-time employment decreased for the Asian/other PI/Native HI group across all analyzed mental health disorders. See Figures S1–S4 of the online supplement for the prevalence of mental health disorders over time and by racial-ethnic group.

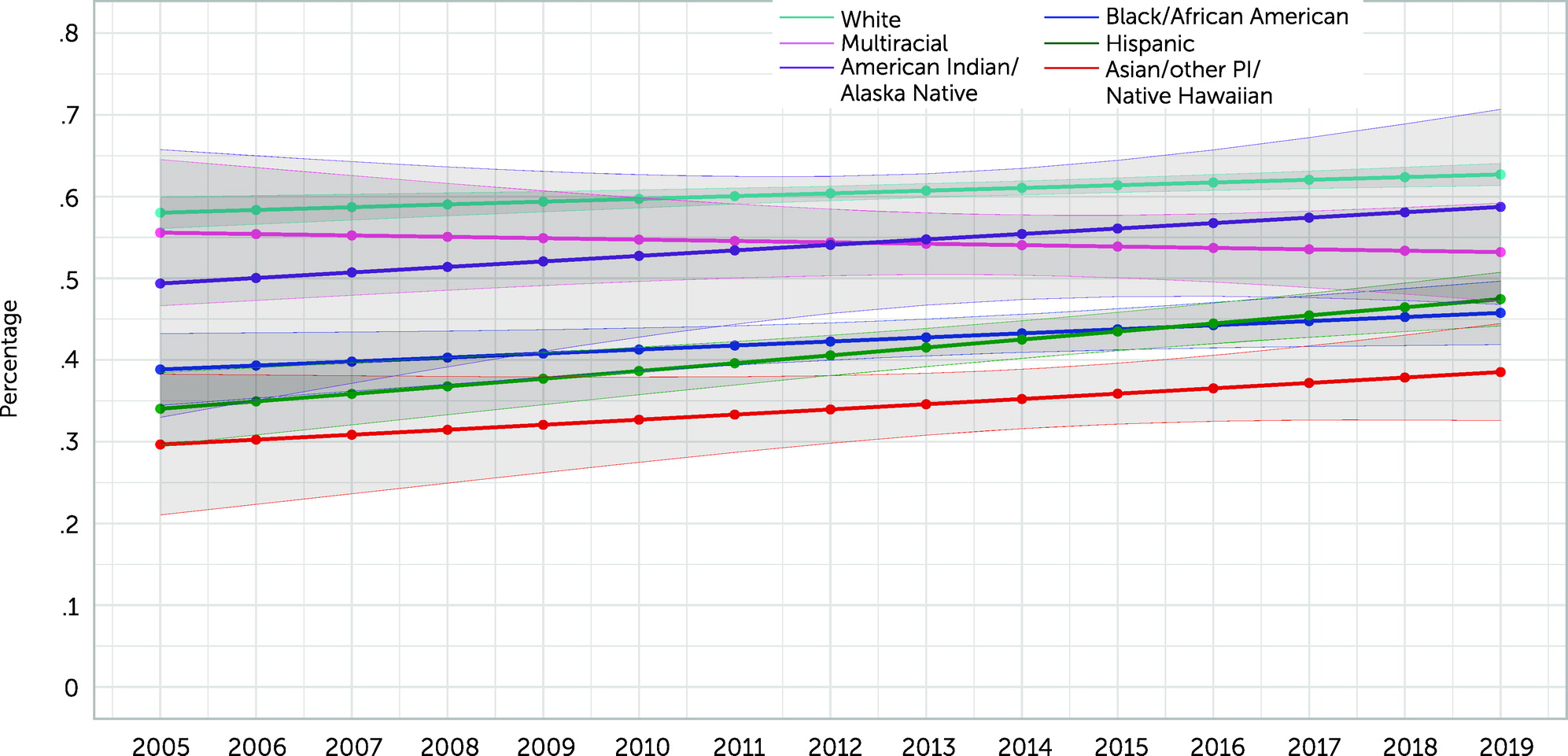

Past-Year Major Depressive Episode

From 2005 to 2019, the prevalence of treatment among White people with major depressive episode increased from 57.7% (N=1,121 of 2,083; all percentages are weighted) to 63.3% (N=1,753 of 2,919). Treatment prevalence increased among Asian/other PI/Native HI people (40.8% [N=17 of 76] to 44.0% [N=59 of 155]), Black/AA (42.9% [N=102 of 295] to 43.0% [N=159 of 413]), Hispanic (32.6% [N=124 of 399] to 48.3% [N=293 of 676]), multiracial (38.5% [N=47 of 111] to 56.1% [N=125 of 232]), and American Indian/Alaska Native people (41.5% [N=28 of 54] to 49.6% [N=32 of 64]) but remained lower than that of White people (see Figure S5 in the online supplement).

Overall, only disparities between White people and Hispanic people decreased (slightly). The interaction risk ratio for the association between White people and Hispanic people by survey year was 1.02 (95% CI=1.01–1.03) (

Table 1). Predicted probabilities of receiving treatment showed that only the gap in predicted receipt of treatment between White and Hispanic people decreased (slightly) (

Figure 1).

The magnitude of the disparities in treatment use between White and Asian/other PI/Native HI, Black/AA, multiracial, and American Indian/Alaska Native people did not meaningfully change from 2005 to 2019 (Table S4 in the online supplement). However, the magnitude of the disparity between White and Hispanic people decreased slightly (percentage-point difference=−25.1% in 2005 to −14.9% in 2019).

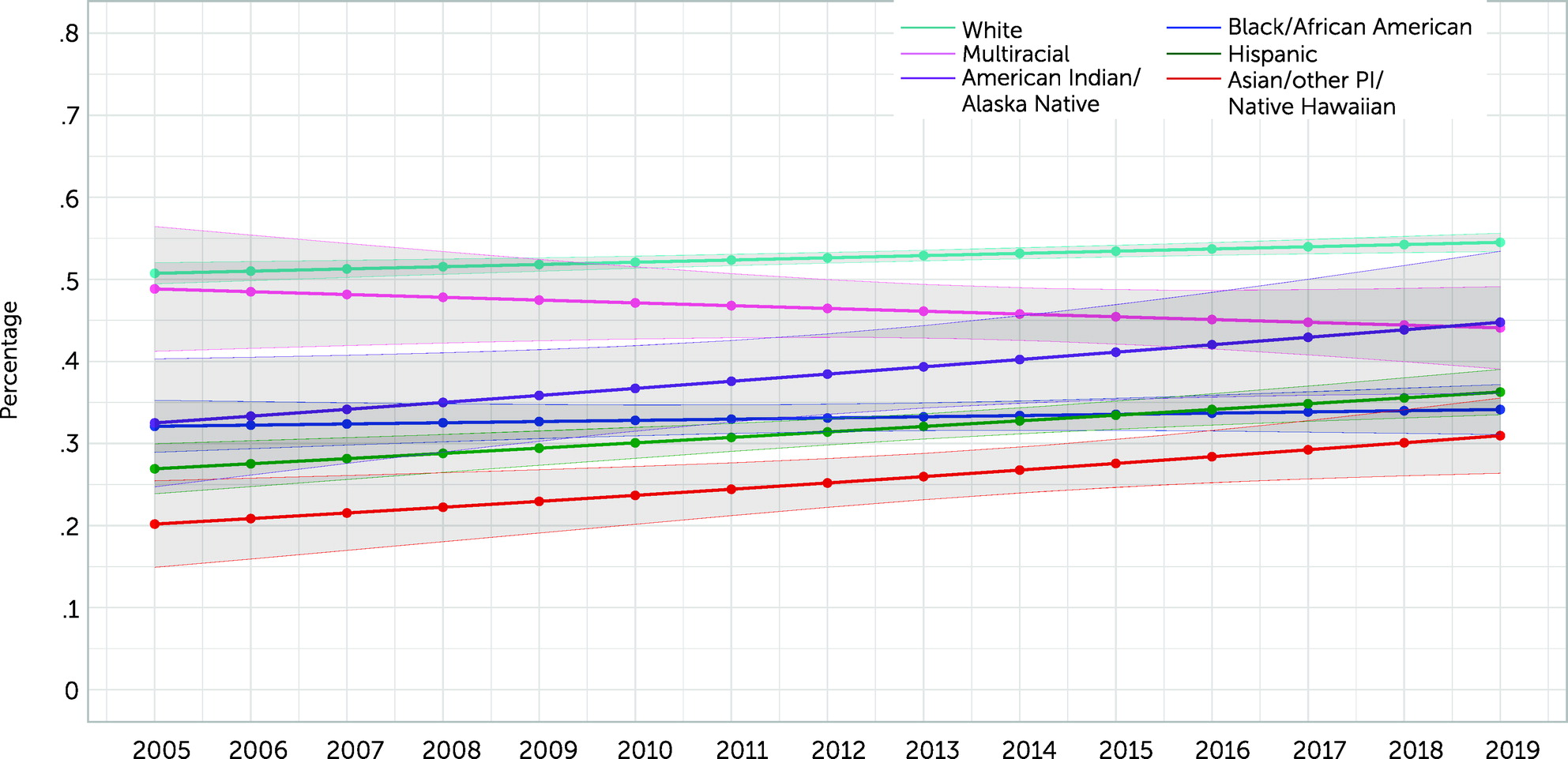

Past-Year Serious Psychological Distress

The prevalence of treatment among White people with serious psychological distress increased from 50.4% (N=1,612 of 3,606) to 55.3% (N=2,472 of 4,684). Although treatment prevalence rose among Asian/other PI/Native HI (20.9% [N=31 of 171] to 30.6% [N=87 of 316]), Hispanic (28.5% [N=209 of 800] to 34.8% [N=444 of 1,260]), multiracial (38.2% [N=67 of 175] to 46.6% [N=175 of 388]), and American Indian/Alaska Native (24.2% [N=36 of 108] to 40.6% [N=40 of 101]) people with serious psychological distress, it remained lower than that among White people. Treatment among Black/AA people with serious psychological distress decreased slightly (36.2% [N=170 of 611] to 35.0% [N=258 of 885]) (Figure S6 in the online supplement).

Overall, only disparities between White and Hispanic people with serious psychological distress decreased (slightly; interaction RR=1.02, 95% CI=1.00–1.03) (

Table 1). Results from predicted probabilities of receiving treatment for people with serious psychological distress mirrored results for people with a major depressive episode (

Figure 2).

From 2005 to 2019, among people with serious psychological distress, no meaningful change in the magnitude of the disparities was seen between White people and people from the other racial-ethnic groups (Table S4 in the online supplement).

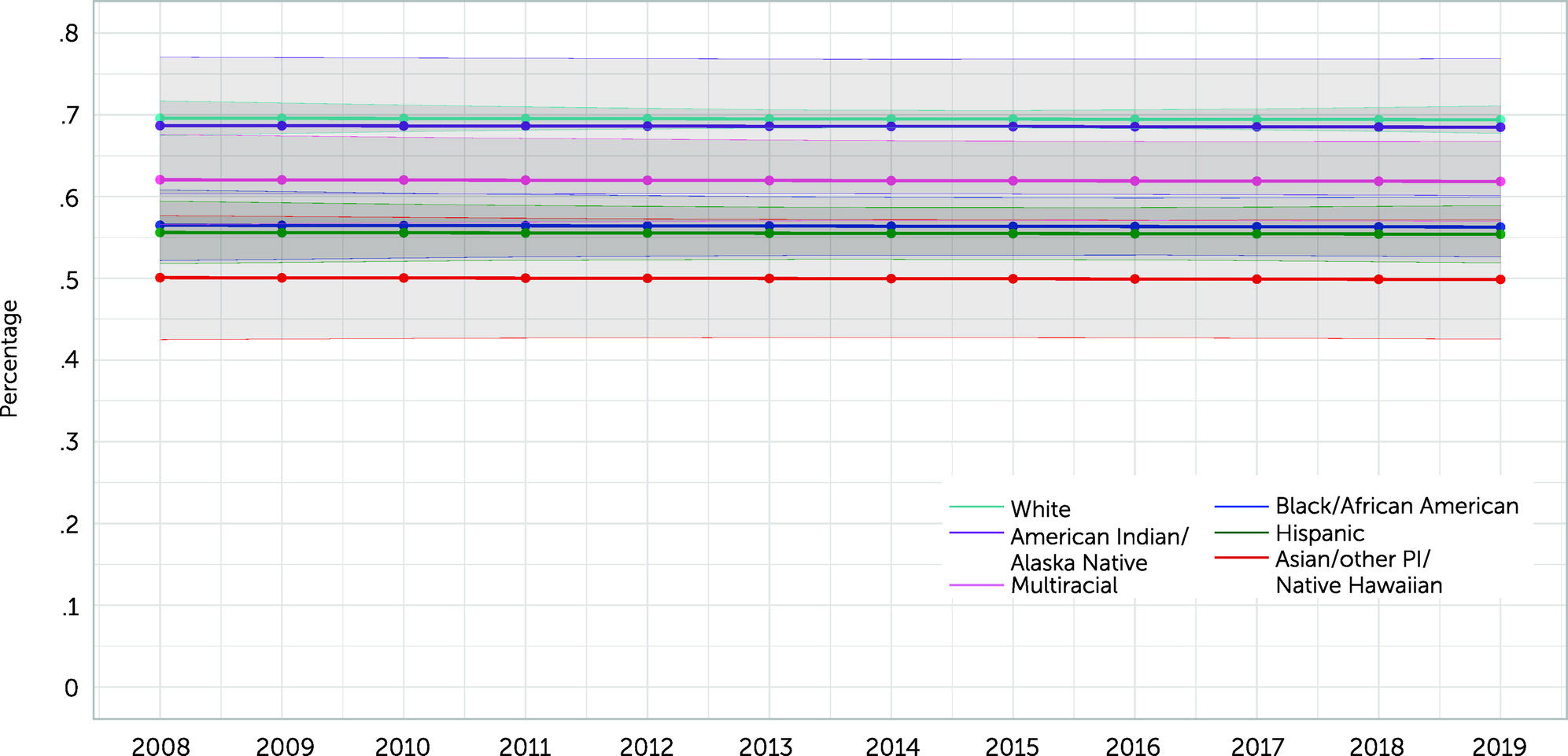

Past-Year Serious Mental Illness

The prevalence of treatment increased among White, Hispanic, and multiracial people with serious mental illness from 2008 to 2019 (67.9% [N=720 of 1,124] to 69.8% [N=1,350 of 1,998], 47.7% [N=85 of 193] to 51.7% [N=237 of 442], and 60.5% [N=41 of 69] to 62.5% [N=106 of 167], respectively). However, treatment decreased among Asian/other PI/Native HI, Black/AA, and American Indian/Alaska Native people with serious mental illness (61.2% [N=13 of 40] to 49.9% [N=45 of 102], 58.6% [N=75 of 151] to 55.8% [N=120 of 245], and 91.4% [N=17 of 24] to 57.6% [N=27 of 42], respectively) (Figure S7 in the online supplement).

Survey year was not significant in the regression that modeled any mental health treatment among those with serious mental illness as a function of survey year only. Therefore, the final (more parsimonious) model among those with serious mental illness had no interaction term between survey year and race-ethnicity. The model indicated that observed disparities in treatment were sustained over time for Asian/other PI/Native HI (RR=0.72, 95% CI=0.62–0.83), Black/AA (RR=0.81, 95 CI=0.76–0.86), Hispanic (RR=0.80, 95% CI=0.75–0.85), and multiracial (RR=0.89, 95% CI=0.82–0.97) people with serious mental illness compared with White people with these conditions (

Table 1). Disparities between White people and American Indian/Alaska Native people did not change (RR=0.99, 95% CI=0.87–1.12). Predicted probabilities showed that the gap in predicted treatment between White people and those from marginalized groups did not change (

Figure 3).

Among people with serious mental illness, the magnitude of the disparities from 2008 to 2019 between White people and people from the marginalized groups studied did not change meaningfully, except for the disparity between White people and American Indian/Alaska Native people, which increased significantly (percentage-point difference=23.4% to −12.2%) (Table S4 in the online supplement).

Discussion

This study used nationally representative data to document trends in racial-ethnic disparities in mental health treatment use among adults with a past-year major depressive episode or serious psychological distress (2005–2019) and adults with serious mental illness (2008–2019). Disparities between White people and people from marginalized groups persisted, except for some slight decreases in disparities between White and Hispanic people. With this study, we extended the prior literature (

11) to 2019 and focused on mental health treatment use among people experiencing three types of mental health disorders for which Black and Hispanic people are less likely to receive treatment compared with White people. We also examined national disparities between White adults and American Indian/Alaska Native adults, a group with substantial mental health–related needs and low access to care (

34).

The observed disparities may partially have been caused by coverage issues not adequately addressed by the ACA. Between 2013 and 2017, White people had the highest insured rates when compared with Black and Hispanic people (

35), even though Black and Hispanic adults are twice as likely as White adults to have low income and, therefore, are more likely to qualify for Medicaid (

36). Furthermore, whereas states that had expanded Medicaid access by 2018 through the ACA had larger decreases in disparities in coverage compared with states that did not expand access (

36), half of Black working-age adults and more than one-third of Hispanic working-age adults lived in states that had not expanded Medicaid by 2018. Moreover, although American Indians/Alaska Natives are disproportionately poorer than the general U.S. population (

37), they are more likely to be completely uninsured, despite increased access to Medicaid (

38). Therefore, low-income marginalized groups may remain systematically excluded from receiving insurance, which may partially explain these persistent disparities.

Structural barriers may also contribute to the observed disparities. A study (

39) that used 2011 NSDUH data determined that adults with perceived unmet need reported a structural barrier (e.g., cost, inadequate insurance coverage) more often than an attitudinal barrier (72% vs. 47%). Although some studies (

40) have focused on describing the role of stigma as a barrier to treatment, other studies have found that marginalized groups have positive attitudes toward treatment seeking (

41), suggesting that systemic barriers, rather than individuals’ own attitudes, may explain observed disparities. Geographic factors, such as distance to providers (

42), should also be considered in future studies as potential mechanisms for observed disparities. These issues are particularly acute among American Indian/Alaska Native people, of whom about one-third live on remote reservations (

43).

Of note, our study found that disparities between White people and Asian/other PI/Native HI people did not meaningfully change. Other potential barriers encountered by this group deserve closer attention. For instance, the “model minority” myth is the stereotype that Asian Americans are more successful than other marginalized groups, because of their stereotypical stronger work ethic and perseverance (

44). Internalized beliefs of this myth among Asian Americans have been associated with reductions in help-seeking attitudes regarding mental health issues (

45). Furthermore, research has suggested (

46) that Asian American people may report psychosomatic complaints resulting from an underlying mental illness, which may not be accurately diagnosed by some health care providers, leading to this population’s lower rates of mental health treatment. However, in a study by Lee et al. (

47), Asian American people with psychosomatic depressive symptoms sought mental health treatment more than White, Black, or Hispanic people, thereby contradicting this hypothesis. This finding suggests that somatization may not explain observed trends, indicating that more work is needed to determine the root causes of low mental health treatment use among the Asian American community. The Asian/other PI/Native HI category in our study encompassed numerous and diverse subgroups; potential for significant differences across subgroups in mental health outcomes and treatment access warrants investigation.

Observed reductions in treatment disparities between White and Hispanic people may have been partially caused by increased public and private insurance among Hispanic people, in combination with lower social stigma among the Hispanic population toward seeking mental health treatment (

41) and increased federal funding for Hispanic-serving organizations (

48). However, more research is needed to parse trends within Hispanic or Latinx subgroups and to elucidate stronger hypotheses for this observed reduction.

Although our study focused on national trends, we acknowledge the importance of elucidating mechanisms to explain observed disparities, such as socioeconomic status (SES). Our results represented the total effect of race-ethnicity on mental health treatment use trends over time; we did not adjust for SES, because the association between SES and health outcomes is often influenced by race-ethnicity (

49), making SES a potential mediator instead of a confounder. Future studies should investigate mechanisms and examine SES as a potential mediator of the relationship between race-ethnicity and mental health treatment use trends.

Limitations of our study should be considered. The mental health disorder measures relied on self-reports from audio computer–assisted self-interviewing rather than on clinician interviews. However, the major depressive episode (

28) and serious psychological distress (

29) measures have been validated in other studies, and the serious mental illness measure was constructed to reduce the likelihood of bias (

31). The self-reported measures for mental health treatment may have been susceptible to recall and reporting bias. However, our results were consistent with findings from other data sources with non–self-report measures (

11), increasing confidence in our findings. The binary responses for any mental health treatment used in our study did not capture duration of treatment. However, a study (

15) has found that African American and Hispanic people received fewer outpatient visits than White people, indicating that disparities are present in the amount of mental treatment received as well. Because of the broad racial-ethnic categorizations available in the public-use NSDUH, we were unable to parse the unique experiences of racial-ethnic subgroups. Moreover, multiracial people are becoming an increasingly populous group in the United States (

50), yet measures of this group have been highly variable and contextually dependent, including the measure used in this study. These major limitations should be considered when designing surveys and disseminating data for public use. Finally, race-ethnicity is a social construct, and there may have been residual measurement error in this self-reported measure.