Specialty managed care organizations that focus on administering behavioral health and substance abuse benefits have emerged as a major force in the mental health care market. These managed behavioral health organizations are now responsible for providing mental health benefits to the majority of privately insured Americans (

1), and they have been shown to dramatically reduce costs compared with indemnity insurance and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (

2,

3). Most managed behavioral health organizations are large, for-profit organizations that contract with public and private employers and operate across wide geographic areas. The industry is dominated by a handful of large managed behavioral health organizations, making it vitally important for us to understand exactly how these organizations operate.

Utilization management is one aspect of managed behavioral health organizations that has sparked considerable controversy. Utilization management techniques have gained widespread acceptance by health plans, with approximately 90 percent of individuals in private health insurance plans being covered by some form of utilization management (

4,

5,

6). The Institute of Medicine defines utilization management as "a set of techniques used by or on behalf of purchasers of health care benefits to manage health care costs by influencing patient care decision-making through case-by-case assessments of the appropriateness of care prior to its provision" (

7).

The most common utilization management techniques are precertification, concurrent review, and case management (

8,

9,

10,

11). Precertification involves the approval of services before delivery. Concurrent review focuses on authorization of additional services and length of stay. Case management incorporates both precertification and concurrent review in more intense, ongoing review of care and tends to focus on high users of care.

While critics of utilization management practices are quick to point out its flaws (

12,

13,

14), most reports to date have been anecdotal, with little systematic evidence to back up their claims. Given the limited availability of information on utilization management patterns in mental health care, data on the actual practices of managed behavioral health organizations are needed.

This paper presents a case study of the utilization management program of a large managed behavioral health organization. We describe the utilization management process of 51 plans managed by United Behavioral Health (formerly U.S. Behavioral Health). We also report on the frequency and types of reviews performed and discuss the extent to which this utilization management program appears to ration use through the denial of services.

Methods

In September 1998 the first two authors visited the San Francisco office of United Behavioral Health to gain an understanding of their utilization management program. The authors met with utilization management staff and observed a few instances of the review process in action as care managers conducted actual reviews on the telephone.

To understand the usual utilization management process at United Behavioral Health, we sampled data from 51 employer-sponsored plans. We included only those plans for which the enrolled population could be defined and for which the utilization management program included standard reviews. A number of plans that had specific programs with additional or alternative reviews were excluded from this study.

The plans we studied had benefit designs covering a full range of behavioral health and substance abuse services, with annual and lifetime limits, copayments, and deductibles varying across the plans. Forty-four of the plans were point-of-service plans allowing members to choose between managed network and unmanaged services with differential coinsurance. Seven plans were exclusive provider organizations covering only authorized services through network providers.

For our analyses we looked at utilization review data from 1997. Claims data were used to determine the total number of members who used services in each plan. More information on the claims database and benefit design at United Behavioral Health can be found in a report by Sturm and McCulloch (

15). The utilization review data were used to determine the frequencies of various types of reviews and the actions associated with each review. Actions were divided into "authorization actions" and "other actions." We defined authorization actions as decisions that led to authorization or denial of services. "Other actions" represented a mix of pending decisions and information-gathering efforts. We were most interested in the authorization and denial patterns, and we focused our analysis on authorization actions rather than other actions.

The review process

United Behavioral Health is the third largest managed behavioral health carve-out organization in the country. Currently it manages mental health and chemical dependency benefits for about 15 million people nationwide. Its providers include psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and master's-level therapists. United Behavioral Health does not capitate or directly employ any providers, and all providers are paid fee-for-service on the basis of one national fee schedule.

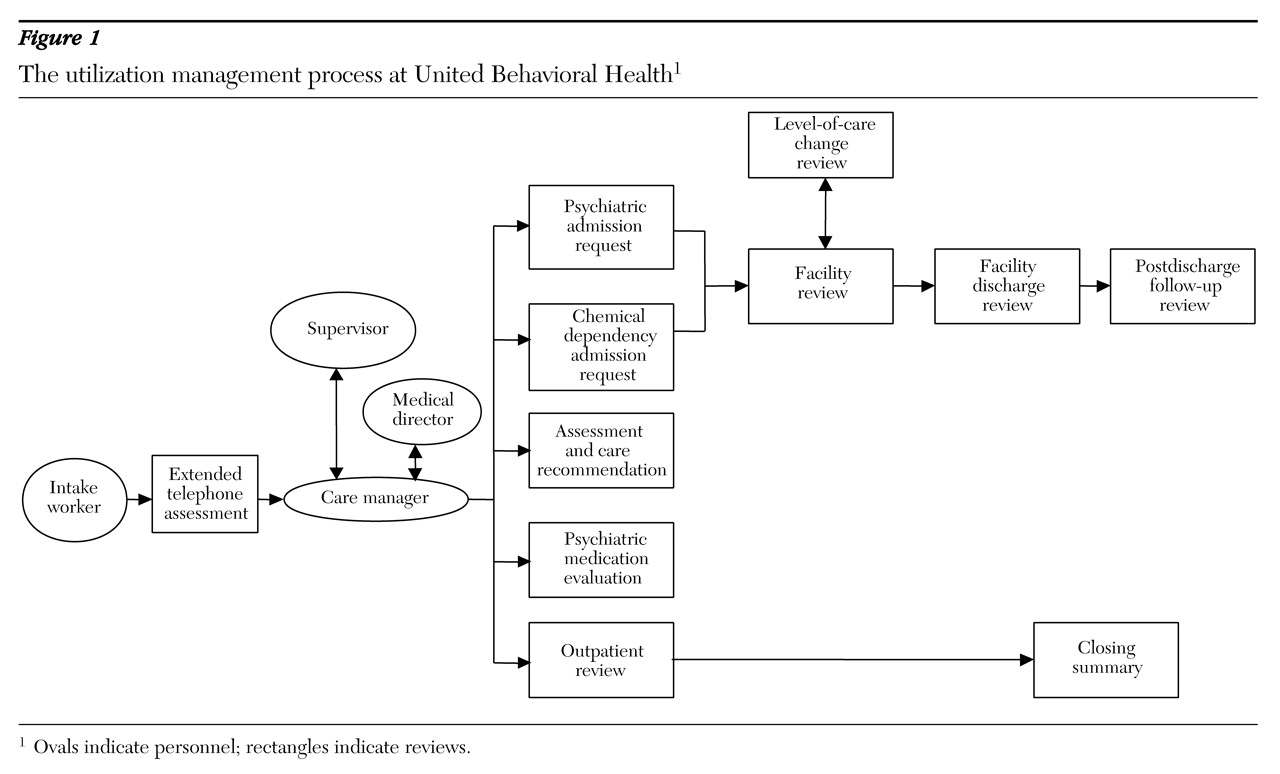

Figure 1 provides a schematic of the utilization management process at United Behavioral Health. Patients call a toll-free telephone number to request specialty mental health care or substance abuse services. Intake workers who are at least master's-level mental health clinicians answer telephone calls from patients and, under routine circumstances, authorize initial outpatient visits (usually ten) without requiring a precertification review. For high-risk patients whose care may be more complicated, the intake worker makes an extended telephone assessment. Depending on the results, the intake worker may authorize initial outpatient services or transfer the patient to a care manager for an evaluation for more intensive services.

Care managers make the majority of the utilization review decisions. This group is a mix of master's-level clinicians and psychologists, with an average of eight years of clinical experience. Occasionally a care manager receives a request for services directly from a patient, but the majority of requests come from mental health providers who either send in written requests forms or participate in brief telephone interviews.

The care managers meet in teams daily to go over cases. A supervisor and a medical director are assigned to each team. Supervisors sign off on any denial of services and assist the care managers with difficult clinical decisions. Medical directors are involved in any denial decisions related to more intensive treatments such as admission to inpatient services or the concurrent review of acute care. The medical directors are also involved in the appeal process for denials. The utilization management program does not use explicit guidelines or algorithms for decision making. Instead, it relies on the initial training of utilization management staff and the daily team meetings to provide consistency in the utilization management decisions.

The utilization management program typically carries out 11 types of review, as described in

Table 1. Seven reviews require decisions about whether to authorize or deny services: requests for psychiatric or chemical dependency admission, level-of-care change, facility review, medication evaluation request, assessment and care recommendation, and outpatient review. Two additional reviews—the facility discharge review and the postdischarge follow-up review—may occasionally be associated with authorization decisions, but their primary purpose is to collect information and facilitate the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Two other reviews—the extended telephone assessment and the closing summary—only gather information and do not require authorization decisions.

Results

Of the 230,532 eligible members continuously enrolled in 1997 in the 51 plans, 4.1 percent (N=9,401) used mental health or substance abuse services, and 3 percent (N=6,995) did so through United Behavioral Health's network providers. Of those who used network providers, 57.4 percent (N=4,016) underwent at least one review of any type. The mean±SD number of reviews for this group was 2.4±2.66; 49.3 percent (N=1,979) had only one review, and 23.1 percent (N=928) had two reviews. Patients with five or more reviews made up 11.4 percent (N=458) of patients who underwent reviews and accounted for 37.7 percent (N=3,630) of the total number of reviews, which was 9,639. One patient received 59 reviews during 1997.

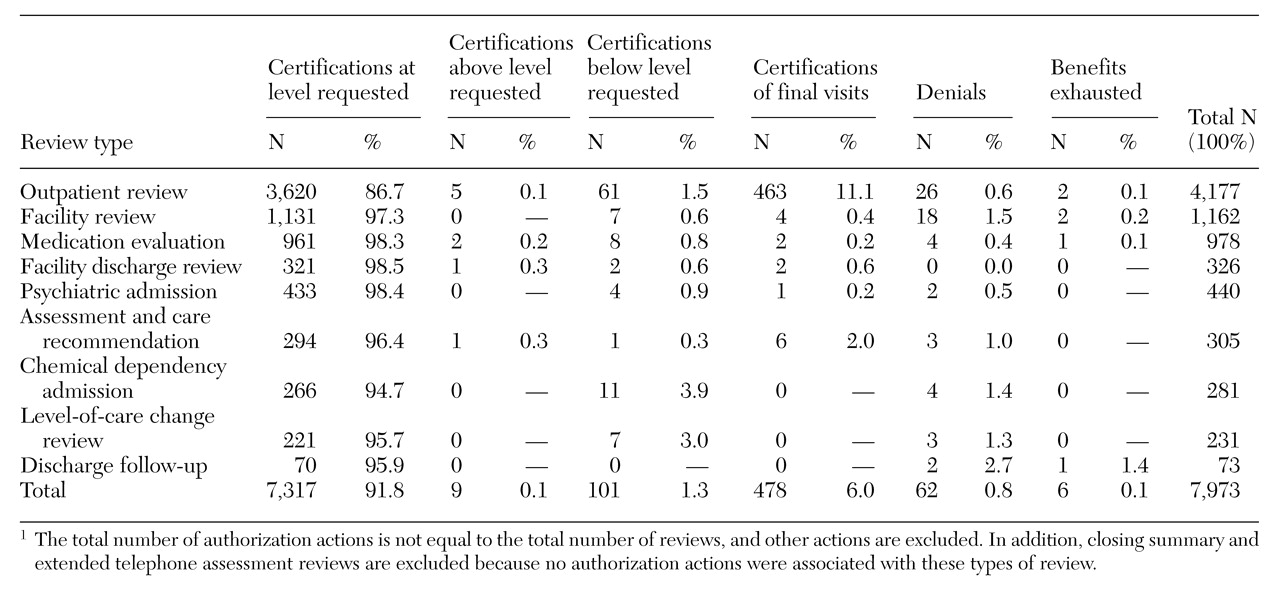

Table 1 lists and describes the different types of review in order of frequency. The most common type was outpatient review (concurrent review for additional outpatient therapy visits), representing 46 percent of the total. The second most common was facility review (concurrent review for additional facility days), representing 12.9 percent. In contrast, precertifications such as psychiatric inpatient admission requests and chemical dependency admission requests made up only small percentages, 4.6 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively.

The number of actions (N=10,270) exceeded the number of reviews (N=9,639) because a single review could have multiple actions. For example, one outpatient review could encompass a pending decision and then certification, resulting in two actions for one review. When actions were classified into authorization actions and other actions, we found that authorizations made up 77.6 percent (N=7,973) of the total, and other actions made up 22.4 percent (N=2,297).

As shown in

Table 2, the vast majority of authorizations—91.8 percent—were approved at the level requested by the provider. One less common type of authorization action was certification of final visits, at 6 percent. According to United Behavioral Health, certification of final visits represents an agreement between the clinician and the care manager that the patient will not require services beyond the amount authorized for the final visits. It is unclear to what extent the authorization of final visits might have limited outpatient visits. Rare authorization actions included certifications below the level requested (1.3 percent), denials of services (.8 percent), certifications above the level requested (nine actions), and exhaustion of benefits (six actions).

Table 2 also shows the distribution of authorization actions by review type. In all review types, very few services were denied. Although the proportion of denials was slightly greater for discharge follow-up reviews (2.7 percent) than for other types of reviews, it is based on only two cases and is probably not meaningful.

Very few services were approved at a level lower than requested by the provider. However, a slightly higher percentage of reviews for chemical dependency admissions (3.9 percent) and level-of-care changes (3 percent) were authorized at levels lower than requested, suggesting a tendency to divert patients away from more inpatient chemical dependency treatment and higher levels of inpatient care, but here too the numbers were quite small. Outpatient reviews had considerably more certifications of final visits (11.1 percent) than the other types of review, and a lower percentage of reviews certified at the level requested (86.7 percent). Closing summaries and extended telephone assessments did not have final actions associated with them and are not included in

Table 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to provide a detailed description of the operations of a utilization management program of a large managed behavioral health organization. We were struck by the scope of the program and the considerable energy and resources it required. We found that reviews were not limited to authorization decisions but also included information gathering (extended telephone assessments and closing summaries) and efforts to promote continuity of care (facility discharge reviews and discharge follow-up reviews).

Although an active approach may be lauded for its concern with patient care, it can also be experienced as intrusive and time consuming by providers (

12,

13,

14). We found that utilization management was frequently employed, with more than half of the patients who used United Behavioral Health network providers undergoing some type of review. In a survey conducted by the American Medical Association in 1990, psychiatrists reported spending more time dealing with external reviewers than did other physicians (

16). The high frequency of reviews thus raises questions about the time costs the review process may have for clinicians.

How do utilization management programs exert their influence? A common perception has been that managed behavioral health organizations are overly restrictive and limit use of services through inappropriately high denial rates (

12,

14). Wickizer and associates (

17,

18,

19) reported that a utilization management program for a managed fee-for-service health care plan had low rates of preadmission denials but appeared to limit hospital care by managing the length of stay through concurrent review. In this study, our findings were somewhat different. Although United Behavioral Health frequently employed concurrent reviews in both inpatient and outpatient settings, we found exceedingly low denial rates regardless of review type or treatment setting. Even if we include authorizations that were approved at lower levels than requested, we found very little overt rationing of services, with the vast majority of services approved at the requested level.

It should be noted that low denial rates do not necessarily mean that utilization management programs are ineffective at altering utilization. Previous studies have found that managed behavioral health organizations substantially reduce costs and utilization rates (

2,

3,

20,

21). In addition to explicit rationing, clinicians' behavior may be shaped by less overt but nonetheless powerful pressures. It has been suggested that managed care may have a more general influence on the practice patterns of clinicians (

22,

23). The low denial rates we observed may be the product of clinicians' learning. Over time, providers may have altered their clinical decision-making patterns to conform with the intensity of services that managed behavioral health organizations will reimburse. Unfortunately, we do not have access to United Behavioral Health data from before the implementation of the utilization management program to address this question.

Utilization management programs may also exert their influence on clinicians through the sentinel effect or the hassle factor associated with obtaining authorizations. The sentinel effect is a decrease in services given by providers as a result of having a utilization reviewer keep tabs on them (

24), and the hassle factor includes excessive paperwork and time-consuming telephone calls related to the utilization management process (

25). Both of these factors can make providers less inclined to request additional services and would not be reflected in denial rates.

It is also possible that providers have learned how to get their requests authorized. Rather than changing their clinical behavior, they may simply be becoming more savvy about navigating the utilization management process and getting requests approved. Given the decreased utilization associated with managed behavioral health organizations (

20), however, increased ability to navigate the process seems unlikely to explain the low denial rates we observed.

Managed behavioral health organizations may also control utilization through the selection of providers for their network. Some managed behavioral health organizations may use provider profiling to remove clinicians who request too many services from their panels (

26). High denial rates may not be necessary if the managed behavioral health organization builds its network with clinicians who provide levels of care consistent with expected utilization rates.

Given the public's strong negative sentiment toward managed care, there may be increasing pressure on managed behavioral health organizations to minimize their overt denial of care. In this highly competitive mental health care market, low denial rates in addition to cost savings may be attractive to purchasers of mental health benefits. Our study reports only on employer-based plans and does not examine managed behavioral health organizations in the public sector. As state and local governments increasingly contract with managed behavioral health organizations, it will be important to see how well these utilization management techniques translate and whether the same low denial rates are possible in the public sector.

Several important issues are not examined in this study. Our analysis does not address the appropriateness of the decisions made by the utilization reviewers. We still do not know what the effect of utilization management is on cost or on quality of care. Further research is needed on the cost-effectiveness of the utilization management process and on its impact on quality of mental health care.

Because our analysis was limited to administrative data, we can report only on denials as narrowly defined by United Behavioral Health. There may be denial equivalents that limit care but are not captured in utilization management records. For example, we cannot measure the content of the interactions between provider and care manager and do not know how much negotiation and compromise go into the authorization process. Care managers may tell providers what they will authorize rather than ask providers what services are needed, and this process may be recorded as an approval at the level requested. For a more complete picture of the utilization management process, it would be important to examine the perceptions of United Behavioral Health providers.

Our site visit was used to inform our quantitative analysis. We did not conduct a formal qualitative study of the utilization management program, which might have provided useful additional information. It is possible that the 51 plans we analyzed are not representative of the utilization management program as a whole. However, according to United Behavioral Health officials, the utilization management program should not differ greatly among plans, and in a preliminary look at the excluded plans, we found similar denial rates.

The generalizability of our results is limited, since we report on a single utilization management program. It is unclear whether the utilization management process and authorization rates we describe are unique to this particular organization or whether these features are characteristic of the industry. That United Behavioral Health has given us access to its data could suggest that its utilization management process is different from the process used by other companies. Utilization management programs vary widely in personnel and the clinical criteria used to authorize care (

8,

11). An interesting question is whether denial rates would be different in a system that uses explicit guidelines for review.

Conclusions

Although a number of writers have deplored the high denial-of-care rates in utilization management programs, this study found very low denial rates at United Behavioral Health. While it remains unclear how utilization management programs exert their influence, access to care at this particular managed behavioral health organization does not seem to be limited through overt denial of services. Further studies are needed to determine the precise mechanisms utilization management uses to control utilization. Especially important would be to investigate whether utilization management shapes provider behavior directly or through a hassle factor. For this, some means of measuring the hassle factor is needed. A survey of United Behavioral Health providers to help address this question is planned.

The large number of utilization reviews raises additional questions about the cost of the review process in clinicians' time as well as in opportunity costs. How much time and money does the utilization management process consume at managed behavioral health organizations? Can any of the process be eliminated without affecting quality of care? Future research should examine the value added for the resources spent on the utilization management process.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health through grants MH-54623 and MH-00990. The authors thank United Behavioral Health for access to its data and its organization, and Joyce McCulloch, M.S., Brian Cuffel, Ph.D., and William Goldman, M.D., for their help. They also thank Roland Sturm, Ph.D., Ken Wells, M.D., and Arlene Fink, Ph.D., for comments on an earlier version of this article, and Xiaofeng Liu, M.S., for statistical support.