Of particular note is the disparity in the success of pharmacotherapy of depression between children and adolescents and adults. However, this finding is based on a paucity of well-designed drug treatment studies of affective disorders among children and adolescents. Over the past 30 years, the investigation of pharmacotherapy of child and adolescent affective disorders has generally progressed through three phases. These periods can be viewed as the early studies, the tricyclic antidepressant phase, and the second-generation antidepressant phase. Each has added a distinct understanding to our knowledge base.

The tricyclic phase

The first well-designed, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tricyclic antidepressants for childhood depression was reported in 1987 by Puig-Antich and associates (

15). It examined use of imipramine for preadolescents. Earlier reports frequently had small sample sizes and used unvalidated response measures (

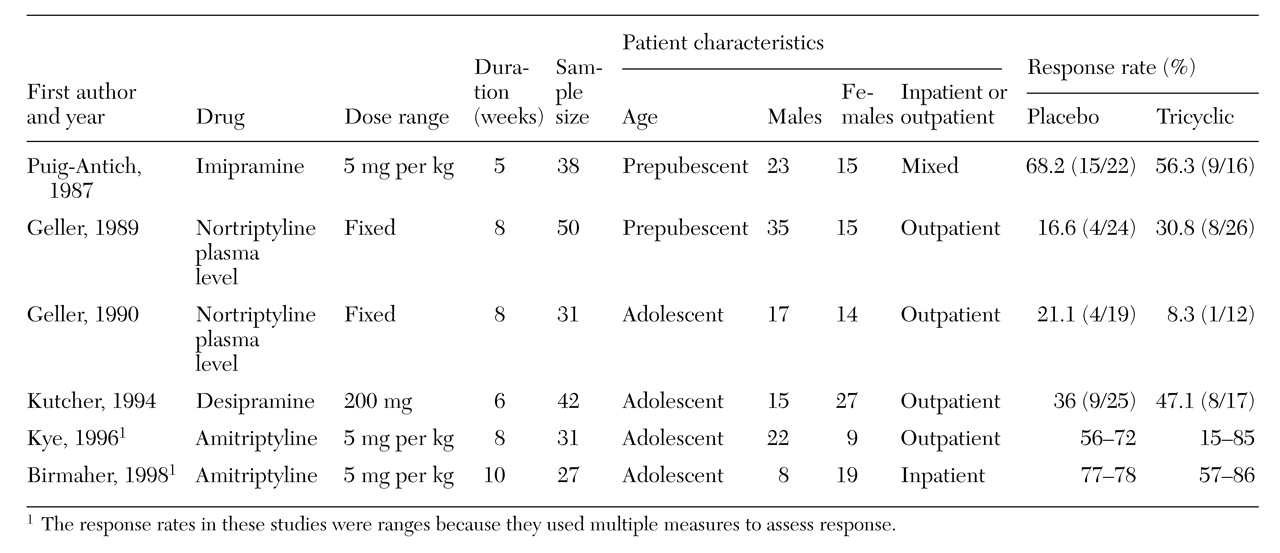

14). Over the next decade additional double-blind studies using amitriptyline, desipramine, and nortriptyline were published. The results were consistently discouraging as tricyclic antidepressants were not found superior to placebo for treating prepubertal or adolescent major depression. These studies are summarized in

Table 1. Meta-analyses of most of the studies further supported the marginal efficacy of these medications (

16,

17).

Although the outcomes of these studies were relatively consistent, the treatment designs varied considerably. Each used a structured interview (K-SADS) to ascertain initial depression status, but the entry criteria subsequently used for the randomization phase differed. Studies by Puig-Antich and colleagues (

15), Kye and associates (

18), and Birmaher and coworkers (

19) required that each subject meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder after placebo washout and at the time that they were randomly assigned to treatment. Geller and associates (

20,

21) and Kutcher and colleagues (

22) required only that scores on depression severity scales remain persistently elevated before randomization.

Earlier studies excluded obviously inappropriate subjects with comorbid disorders, such as those with major depressive disorder who were psychotic and those with active substance abuse. However, only the most recently completed trials have excluded those with family histories of bipolar disorder in an attempt to exclude the bipolar genotype. These differences in sample selection could theoretically have some bearing on response patterns.

Each research group used a well-designed, aggressive pharmacotherapeutic strategy, most tracking plasma levels of tricyclic antidepressants. The length of treatment, which was relatively short in the earlier studies (about five weeks), was extended to ten weeks in successive studies in an attempt to maximize response (

23). Criteria to measure response to the medication were based on a variety of depression rating scales or

DSM symptom severity scores. However, the variability in these parameters was quite extensive. For example, Puig-Antich and colleagues (

15) and Geller and associates (

20,

21) used a relatively conservative definition of response—a score of less than 2 (indicating minimal symptoms)—on the K-SADS interview on most of the questions about

DSM criteria for a major depressive disorder. The studies by Kutcher and associates (

22), Kye and coworkers (

18), and Birmaher and colleagues (

19) used a wider definition of response, which included improvement rates on depression severity scales and analyses of response-remission status either among subjects who left the study—with the last observation carried forward—or among subjects who completed the study. These methodologies are frequently used in adult pharmacotherapy reports.

With the exception of the study by Birmaher and associates (

19) that examined chronically depressed inpatients, the later studies noted some trends suggesting response as measured by scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S).

The investigation of the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants for treating child and adolescent affective disorder is most likely at an end because of the mediocre response profile of these drugs. The cardiotoxicity of the tricyclic antidepressants, which makes them particularly lethal in overdoses, is also problematic (

24). The toxicity is most striking when compared with the wide margin of safety in overdoses of SSRIs. However, this phase of investigation advanced the methodological implementation of pharmacotherapy of depressed children by standardizing diagnostic ascertainment and operationalizing response measurements.

Also, these investigations shed light on the drug response characteristics of children and adolescents with major depressive disorders. At the outset, most youths studied have moderate to severe depression as measured by either duration of the disorder or depression severity scores on standardized rating scales. Evidence suggests that those who view themselves as most severely depressed may respond less favorably to tricyclics (

19), which implies that self-ratings of depression severity could be a valuable parameter to assess response patterns. The importance of self-ratings is further supported by the fact that clinicians tend to overrate improvement during treatment studies (

25). A complementary issue is the finding that a substantial proportion of treated youths still exhibit subsyndromal depressive symptoms, so that partial remission may be more characteristic of treatment with tricyclic antidepressants (

19,

23).

No substantial evidence was found that comorbid diagnoses influenced recovery in youths treated with tricyclics. However, because comorbid problems are prevalent (

26), ratings of recovery and remission from depression may be influenced by impairment resulting from comorbid disorders (

27). The characteristics of the rating scales used to assess depression severity and response with the tricyclic antidepressants were infrequently analyzed. Although the BDI and the HDRS are validated indicators of affective disorder in adolescent samples (

28,

29) and the Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS) has been validated in child samples (

30), only three instruments have been shown to be sensitive to pharmacotherapy in adolescents: the BDI, K-SADS-derived symptom severity scales (

23), and the HDRS (Ambrosini and Tan, unpublished data, 1998). These instruments have not been reported to be sensitive to treatment effects in prepubertal children. Furthermore, the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), which is used frequently for preadolescents, is not a sensitive scale for identifying major depressive disorder in outpatient samples (

31), nor has it been shown to be sensitive to pharmacotherapy.

The second-generation antidepressant studies

Even though the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been available for about a decade, few double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of their efficacy in depressed youths have been conducted. The lack of studies primarily reflects the general difficulty of introducing new pharmaceuticals in child populations. Secondly, the pharmaceutical industry has been reluctant to introduce antidepressant drug trials in an age group that was shown to be nonresponsive in previous trials of antidepressants. The proper methodological requirements for these studies also were debated for the reasons noted above.

Nonetheless, studies using fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine have been completed. The overall results from these studies are more encouraging than those reported for the tricyclic antidepressants, as indications have been found of their superiority to placebo. However, these early findings must be viewed cautiously, as the outcomes are inconsistent either within or across studies. The results from the fluoxetine (

32) and venlafaxine (

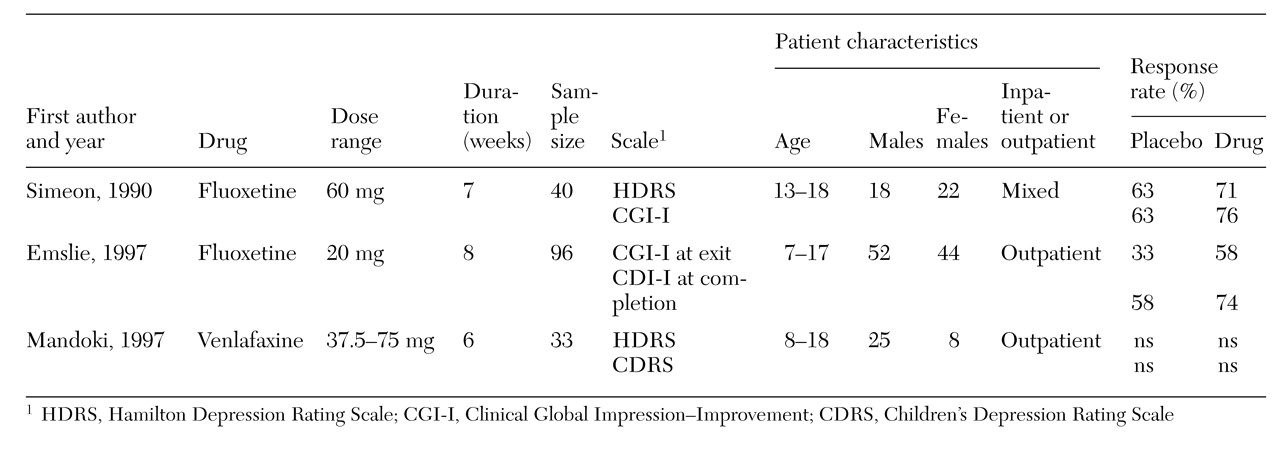

33) studies, the only reports currently published, are summarized in

Table 2.

Of the two fluoxetine studies (

32,

34), only that by Emslie and associates (

32) noted a significant drug effect. The study investigated use of a fixed-dose paradigm (20 mg a day) in a mixed sample of 96 depressed children and adolescents. Subjects were treated for eight weeks following a three-week assessment and a one-week placebo lead-in. Diagnoses were ascertained with K-SADS and DICA interviews. At the time of random assignment to fluoxetine or placebo, each subject had a CDRS score greater than 40, indicating persistence of depressive symptoms, and continued to meet diagnostic inclusion and exclusion criteria. Primary response measures were weekly scores on the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) and CDRS scores.

At study exit, responses of subjects on fluoxetine were significantly superior to those on placebo. Fifty-six percent improved much or very much as measured by the CGI-I, while only 33 percent of placebo-treated youths responded. However, among study completers, no significant difference was found in response between subjects given fluoxetine (74 percent) and those given placebo (58 percent). This disparity was attributed to the larger proportion of nonresponding subjects who dropped out of the placebo group. When response as measured by the CGI-I was categorized by the time required to attain two consecutive weeks of much or very much improvement, fluoxetine again was superior to placebo.

Emslie and associates (

32) further analyzed weekly CDRS scores as a continuous variable and followed a last-observation-carried-forward methodology. With this approach, the exit CDRS scores of subjects who did not complete the eight-week protocol were carried forward to fill in for successive missing values. This analysis supported the CGI-I findings and also found that a significant treatment effect with fluoxetine first emerged after five weeks of treatment. Neither age nor sex affected the results. However, secondary measures of general psychiatric symptomatology as assessed by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, global functioning as measured by the Child Global Assessment Scale, and self-reported improvement as measured by the CDI and the BDI did not show a significant difference between the drug and placebo; however, the analyses did show a significant decrease in symptoms from baseline to study exit. The discrepancy among assessment measures was not explained. Furthermore, although a statistically significant improvement was noted, complete remission as defined by a CDRS score of less than 28 was uncommon; the exit CDRS mean score was 38.4, and the baseline CDRS mean score was 58.5.

Simeon and coworkers (

34) studied a mixed sample of 30 outpatient and inpatient adolescents who had a baseline HDRS score greater than 20 and a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. However, the method of ascertaining the diagnosis was not specified. Fluoxetine was titrated to a fixed dose of 60 mg per day, and treatment continued for seven weeks. Response measures were changes on the HDRS, the CGI, the Raskin Depression Scale, the Covi Anxiety Scale, and the 58-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist. Although a significant improvement was noted by three weeks of treatment, response to fluoxetine was not superior to response to placebo. Overall, approximately two-thirds of patients responded with either treatment as measured by improvement on the HDRS of greater than 50 percent.

Only one treatment study of a new second-generation non-SSRI antidepressant for treating depressed youths has been published. Mandoki and colleagues (

33) compared venlafaxine to placebo among 40 children and adolescent outpatients. After a one-week placebo washout, venlafaxine was titrated to a fixed dose of either 37.5 mg a day for children 12 years old and younger or 75 mg a day for adolescents 13 years old and older. The method of diagnostic ascertainment was not specified. Response was measured after six weeks by changes in subjects' scores on the CDI, the Children's Behavioral Checklist (CBCL), the HDRS, and the CDRS. Weekly cognitive-behavioral-oriented therapy was given concurrently with pharmacotherapy.

Thirty-three subjects completed the study. Over time, a significant improvement was noted on the HDRS, the CDRS, and the CBCL, but no significant medication effect was noted, nor were any improvement effects observed as measured by the CDI. However, the study was limited by the relatively low dose of venlafaxine and the brief treatment period. Of note is the lack of drug effect as measured by the CDI.

A multisite double-blind study of adolescent major depressive disorder that compared paroxetine to imipramine and placebo was recently completed (

35). Early reports of this study suggested that paroxetine was superior to imipramine and placebo; however, considerable inconsistencies were found in the results. The inconsistencies reflected the fact that efficacy of paroxetine depended on which definition of response and which rating scale was used.

The differential recovery rates as measured by different scales and by different definitions of response were recently analyzed in an open treatment study of sertraline for adolescents with major depressive disorder (

36). The report noted that categorical recovery rates can range from 26 percent to 65 percent at six weeks of treatment and from 55 percent to 85 percent at ten weeks of treatment. Furthermore, clinician-rated recovery as measured by the CGI-I consistently gave the highest and quickest recovery rates, while self-rated improvement as measured by the BDI was the most potent measure in the later weeks of treatment.

The investigation of the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants for depressed youths is just beginning. As noted, few double-blind studies have been reported; however, studies of fluoxetine, nefazodone, sertraline, and venlafaxine are currently under way or planned. What has been gleaned from this phase of pharmacotherapeutic studies of child and adolescent major depressive disorder suggests that predominantly serotonergic agents may be beneficial for depressive states in youths and that treatment should be maintained for at least eight to ten weeks. However, the dataset is quite preliminary, and the studies require replication.

In the course of these studies, it also became more apparent that the lack of convergence across several depression rating scales is a potential liability in furthering our understanding of antidepressant treatment in this age group. The findings may be further confused by the continued use in treatment studies of scales such as the CGI scales and the CDRS that are not standardized as both valid and sensitive to pharmacotherapy effects. The different methods of defining response, although standardized, also have not been consistently used. Investigators are not consistent in reporting response rates across continuous and categorical measures at the time of exit from the study, with the last observation carried forward, or among those who completed the study. Therefore, it has not always been possible to compare qualitative and quantitative response rates across studies.