Supported education is a relatively recent rehabilitative intervention for adults with psychiatric disabilities. It is designed to help them succeed in postsecondary educational environments. Program principles are congruent with those of general psychosocial rehabilitation and include integrating participants into normalizing environments; providing access to leisure, recreational, and cultural resources available on college campuses; and establishing educational competencies, such as study skills, attendance, and time and stress management (

1). They also include giving participants opportunities to identify and explore vocational interests; supporting them in mastering the educational environment, such as troubleshooting stress situations and connecting them to support networks; and ensuring peer support from other consumers in supported education or another psychosocial rehabilitation alternative (

1).

Published reports of evaluations of supported education have focused on a variety of outcomes. The evaluations have found increases in college enrollments, preparatory steps to postsecondary education, and competitive employment; increases in self-esteem, empowerment, and quality of life; and a high level of satisfaction with supported education programs (

2,

3,

4,

5). Mowbray and Collins (

6) provided a comprehensive review of the evaluations conducted to date.

An important question yet to be addressed concerns the characteristics of participants most likely to benefit from the intervention. The Michigan Supported Education Research Project was able to enroll a diverse group of almost 400 participants. Evaluations of the project provided evidence that the intervention resulted in positive outcomes (

4,

5,

7). In this study, data from the project were used to identify characteristics of participants in supported education that predict important outcomes.

No previous studies have examined the characteristics of individual participants that are related to key supported education outcomes, although similar studies have been undertaken in the related field of vocational rehabilitation. In vocational rehabilitation, previous work experience and positive attitudes about work have consistently been found to be important predictors of later vocational success (

8,

9). Longer job tenure has also been predicted by previous work history, early satisfaction with the job, and aspects of the work environment (

10).

Demographic and illness-related variables have also been examined, but the findings have been mixed. Mowbray and associates (

9) found that demographic variables contributed to the prediction of work expectations. Xie and colleagues (

10) did not find age, sex, or race to be significant in predicting job tenure. Some have reported that characteristics of the illness, such as diagnosis and severity, are unrelated to vocational outcomes (

8), while others have found relationships between such characteristics and outcomes (

11,

12).

Methods

Intervention

The Michigan Supported Education Research Project enrolled 397 participants in 1994 and 1995. After a baseline interview, each participant was invited to an orientation, received an information packet, and was randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a classroom, group, or individual model. The classroom and group sessions were held on a community college campus. Meetings were held twice a week for two and a half hours each session for two 14-week semesters.

The classroom model used an academic support curriculum adapted from that developed at the Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation (

13). The curriculum has three overall objectives: managing the campus environment, exploring career options, and managing stress. The objectives were implemented by two instructors in a classroom setting. The theory behind the classroom model is the psychiatric rehabilitation principle that skill development and practice should occur in a setting most similar to one in which the skill will be used. Being in a classroom builds participants' confidence in their abilities to enter a "real" classroom in the future.

The aim of the group model was to create a supportive learning environment in which members could explore career and education options and make meaningful, individualized decisions about their future. Two group facilitators, including a mental health consumer, helped group members assess whether postsecondary educational resources and opportunities could be used to help them achieve their future goals. The theory behind the group model was the need to engage supported education students in the college environment and provide support so they would feel enabled to set and pursue their educational goals.

The individual model was a control group; it involved no structured or scheduled intervention. Further information on the intervention is provided elsewhere (

4,

5).

Study participants

Study participants were recruited from the Detroit metropolitan area, primarily from the public mental health system. Eligibility criteria included psychiatric disability of at least one year's duration, a high school diploma or general equivalency diploma obtained or near completion, an interest in pursuing postsecondary education, and a willingness to use mental health services, if needed, during participation.

The initial sample consisted of 397 participants, of whom 208 (52 percent) were female and 189 (48 percent) were male. Consistent with the racial composition of the geographic area, most were nonwhite. A total of 241 (61 percent) were black, 150 (38 percent) were white, and three (1 percent) were from other racial or ethnic groups. The mean±SD age was 36.9±9.39 years, with a range from 17 to 75 years. Nearly half of the subjects had some postsecondary education, about a quarter had only a high school education, and a quarter had not completed high school.

The mean±SD duration of mental illness was 14±10 years. Information about primary diagnosis was available for 240 participants (61 percent). Of these, 163 (68 percent) had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or another psychotic disorder; 59 (25 percent) were diagnosed as having an affective disorder; seven (3 percent) had an anxiety disorder; and 11 (5 percent) had an unspecified disorder.

Because the purpose of the study was to identify characteristics of participants in supported education that were related to positive outcome, the analysis was limited to persons who were assigned to either the group or the classroom and who attended at least the orientation session. Of the 269 persons in either the group or the classroom, 182 attended any part of the program. Of those who attended, 138 completed a six-month interview, and 126 completed a 12-month interview. With the inclusion of those who completed either a 6-month or a 12-month interview, the final sample size came to 147.

Design

Data used in this study were collected at three time points—at baseline and at six and 12 months after the intervention. Interviewers collected information on demographic characteristics; school, work, and psychiatric history; social adjustment and support; symptoms; and self-perceptions. Social adjustment was measured by the Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report (SAS-SR) (

14), which assessed individuals' social adjustment in the domains of family, financial, interpersonal, and housework. Symptoms were measured by the Symptom Checklist-10 (SCL-10), which consists of ten items from the Brief Symptom Inventory (

15) that correlate most highly with the total score (Cronbach's alpha=.87). Other measures of psychiatric disability were diagnosis, which was obtained for 240 participants from the management information system of the community mental health board, and subscales of the Personal Assessment Inventory (PAI) (

16), a self-report of clinical syndromes.

The self-perceptions that were measured included self-esteem (

17), empowerment (

18), quality of life (

19), and school self-efficacy. The scale of school self-efficacy was developed for this intervention and consisted of ten statements representing behaviors important in an educational setting, such as passing tests, for which participants rated their ease of performing on a scale of 1, very easy, to 6, very difficult (Cronbach's alpha=.89).

Support was measured by three items asking about encouragement from family and mental health professionals for work and education. It was also assessed by a series of questions about individuals' social networks. Participants were asked to name and describe individuals they would turn to for various forms of support. Participants were asked to describe the amount of support provided by each person in the network using a scale from 1, not at all supportive, to 5, extremely supportive. The average was calculated for all reported network members.

Analysis

A successful outcome was defined as engagement in productive activity at either six or 12 months after program completion. This dichotomous variable was coded "yes" if the participant reported engaging in either college or vocational education or paid employment. Because the intervention emphasized preparation for education and clarification of goals to help make career decisions, it was anticipated that subjects might decide not to enroll in a higher education program but to pursue a work opportunity instead. Thus employment was considered to represent a successful outcome of the supported education program. Measurement of engagement in productive activity at either the six- or 12-month follow-up was a practical decision to include participants who may have participated in only one of the follow-up interviews.

A previous study identified variables associated with any participation in the Michigan Supported Education Research Project (

20). Having moved a lot in childhood and current receipt of Social Security income were negatively correlated with participation, while parental encouragement about college when the individual was in high school and living alone at the time of program recruitment were positively correlated with participation. For the study reported here, potential relationships between baseline variables and completion of the six- or 12-month interview were examined, and no significant differences were found. Variables tested included group or classroom condition, race, sex, age, cohort, baseline measures of employment, recent (past year) involvement with the state rehabilitative services agency, recent use of mental health services, score on the Brief Symptom Inventory, school efficacy, self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, social support, and all PAI subscales.

Baseline predictor variables were examined in several categories. Demographic variables included gender, age, race (black versus nonblack), marital status, monthly income, receipt of Social Security income, and living situation. Variables related to education and work background included the number of years of previous education, having taken college or vocational classes in the previous year, having a parent who attended college, having a sibling who attended college, having current paid employment, recentness and amount of previous work, number of hours worked in the last job held, prestige of the best job held (Hollingshead AB, unpublished manuscript, 1975), and any productive activity at baseline.

Social variables included parents' encouragement for education, mental health workers' encouragement for education, recent involvement with rehabilitative services, and social support. Self-perceptions included self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life, and school self-efficacy. Illness variables included age of onset of illness, number of years receiving mental health services, diagnosis (schizophrenia, affective disorder, or other), SCL-10 score, PAI subscale scores, SAS-SR score, and the number of times mental health care was sought in the past month.

Bivariate analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between the predictor variables and the outcome measure. Significant predictors were then entered into a multivariate logistic regression model. Model building procedures followed those outlined by Hosmer and Lemeshow (

21); they suggest that variables with p values of less than .25 be considered for inclusion. Because of the large number of variables in this study, the more conservative value of .10 was used.

Variables were entered in four blocks. First, productive activity at baseline was entered to control for the effect of earlier productive activity. Second, condition (classroom versus group) was entered because outcomes might be different for those exposed to different conditions. Third, participants' characteristics that were identified in bivariate analysis to be related to outcome were entered into the model. Finally, interactions of condition and participants' characteristics were examined.

Results

Of the 147 participants in the sample, 77 (52 percent) reported engaging in productive activity at follow-up.

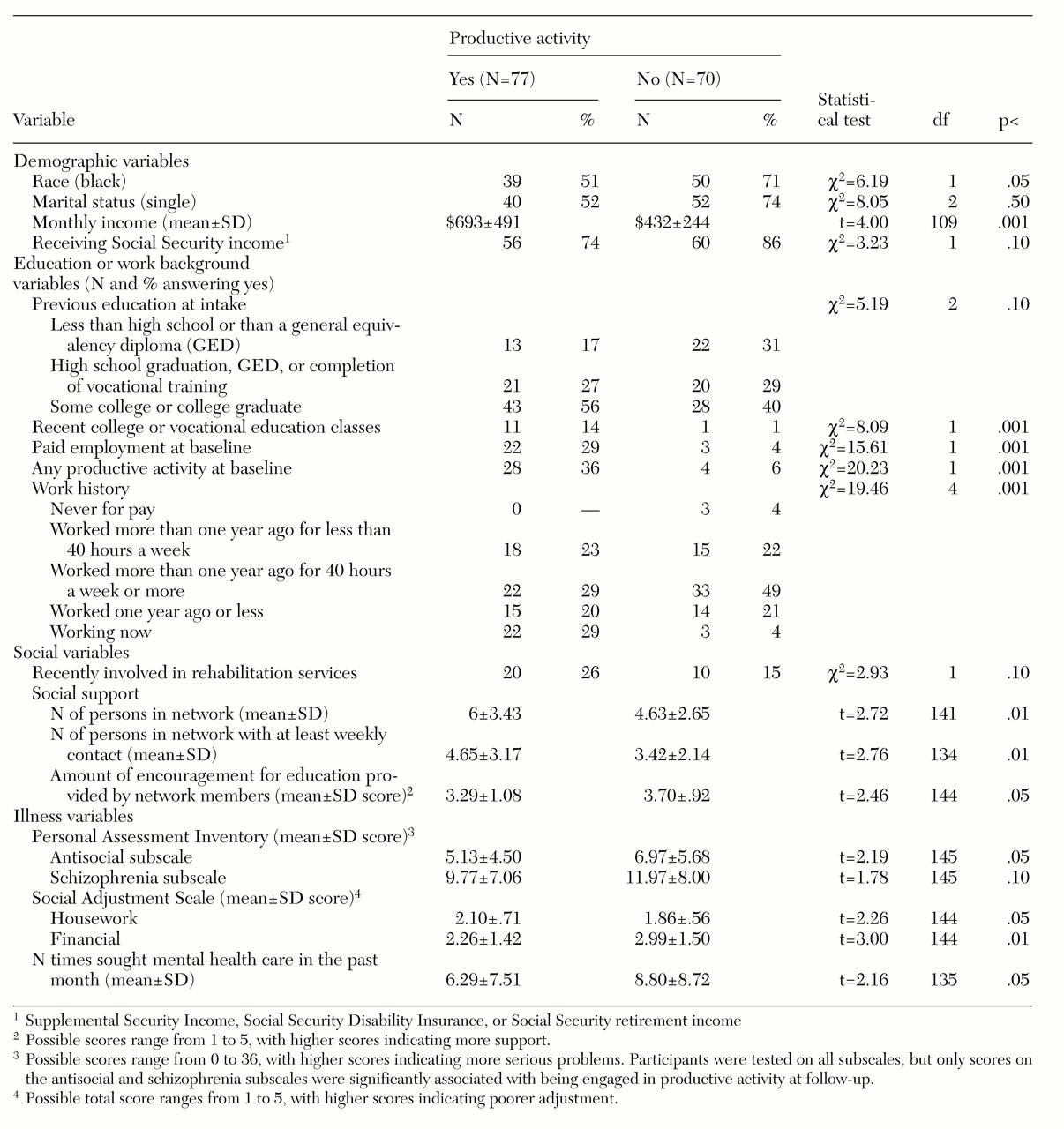

Table 1 provides the significant results of the bivariate analysis. Four demographic variables were found to be related to engaging in productive activity at follow-up. Participants who were black, who were single (never married), who had lower monthly income, and who were receiving Social Security income were less likely to be engaged in productive activity.

Several variables related to education and work background were also found to be significantly associated with productive activity. Participants engaged in productive activity were more likely to have previous postsecondary education, to have recently taken a college or vocational education class, to have been engaged in paid employment at baseline, to have a more recent work history, and to have been engaged in any productive activity at baseline.

Of the social support variables, four were significantly associated with the outcome measure. Participants who reported involvement with the state rehabilitation agency at baseline, who had more people in their support network, and who had more frequent social contact with people in their network were more likely to be productively engaged. On the other hand, individuals who reported encouragement for education from their network at baseline were less likely to be productively engaged at follow-up than those not receiving such encouragement at baseline.

Several variables in the domain of mental illness and social adjustment were related to productive activity. Participants reporting higher use of mental health services and those whose scores on two PAI subscales, antisocial and schizophrenia, indicated more problems were less likely to be engaged in productive activity at follow-up. Finally, two areas of social adjustment measured by the SAS-SR were significantly associated with outcome. Participants with financial difficulties were less likely to be engaged in productive activity. Those who experienced difficulties with housework were more likely to be engaged in productive activity.

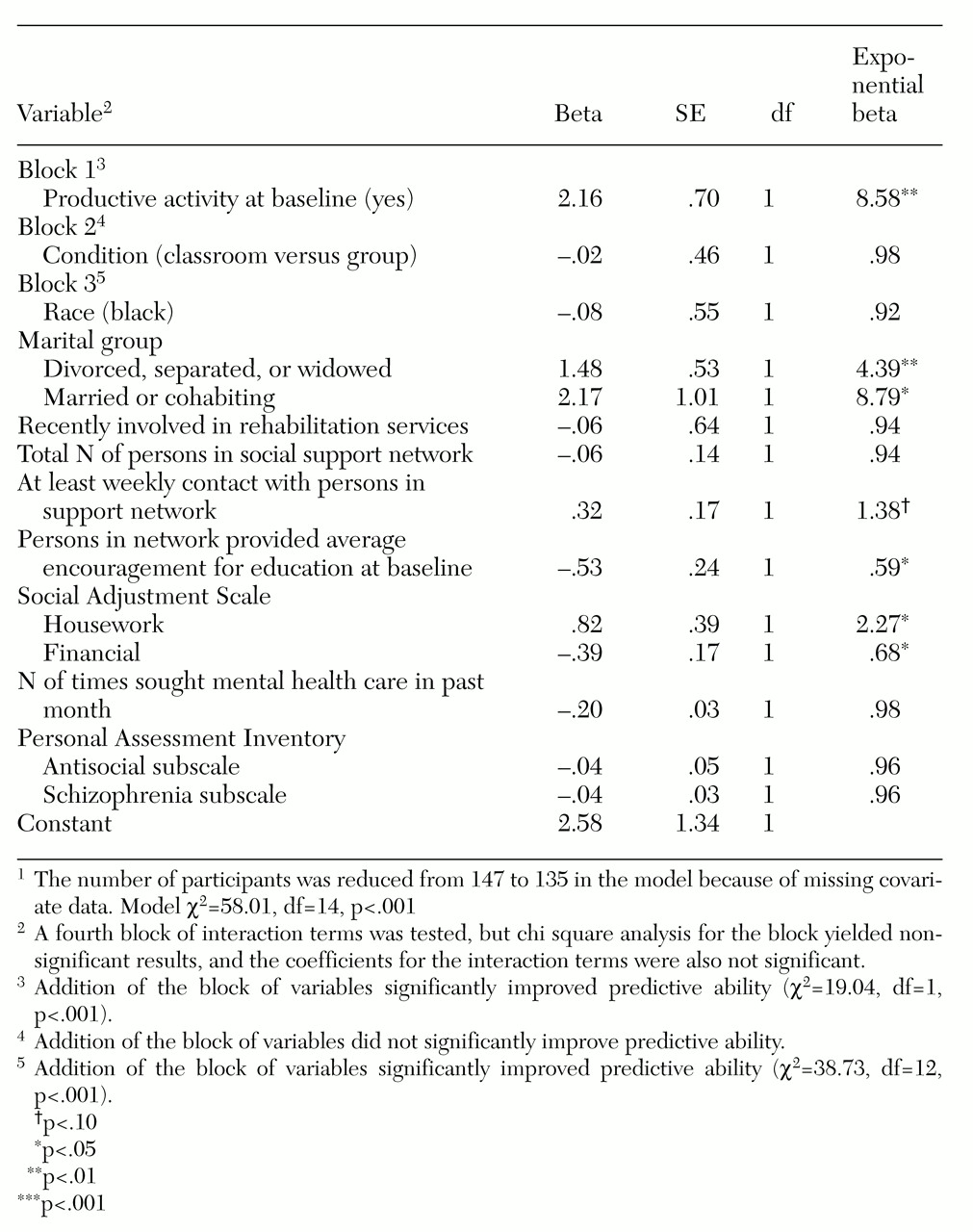

Significant variables were tested in a multivariate model, the results of which are shown in

Table 2. Because variables pertaining to education or work were interrelated, only productive activity at baseline was used in the model. Also, the score on the SAS-SR subscale related to financial problems was used as a proxy for monthly income; the two variables were significantly correlated (r=−.21, p<.01), but fewer participants had missing data on the financial problems subscale.

In the multivariate model, the strongest predictor of productive activity at follow-up was productive activity at baseline, which increased the likelihood of later productive activity by more than eight times. Marital status was the only significant demographic variable in the model; compared with the reference group of single people, those who were divorced, separated, or widowed and those who were married or cohabiting were more likely to be engaged in productive activity.

Two components of social support had an influence on productive activity. One had a positive effect; those reporting at least weekly contact with members of their support network had an increased likelihood of productive activity. One had a negative effect; those reporting higher levels of encouragement for education from their support network at baseline had a decreased likelihood of productive activity.

Two domains of social adjustment were significantly associated with outcome in the multivariate model. Participants who scored higher on the financial subscale, which indicated a lower level of adjustment, were less likely to be engaged in productive activity. Those who scored higher in the domain of housework problems were nearly twice as likely to have a successful outcome as those with lower scores in this domain.

Indicators related to the participant's mental illness—number of times the person sought mental health care in the past month and the PAI antisocial and schizophrenia subscales—were nonsignificant in the multivariate model.

Discussion

The findings of this study are similar to those of research on vocational rehabilitation, which found that previous work experience is a significant predictor of successful employment outcomes. This study of supported education found that productive activity at baseline was an important predictor of productive activity after the intervention. However, other individual characteristics, such as marital status, social support, and social adjustment, were also related to productive activity at follow-up, and when examined together as a block, this set of characteristics had a stronger effect than did productive activity at baseline.

A key predictor was marital status. Participants whose marital status was other than single (never married) were more likely to be engaged in productive activity at follow-up. However, being married or cohabiting at baseline had a stronger effect than being divorced, separated, or widowed. The effect of marriage may reflect qualities of the individual, such as communication skills, that contribute to the ability to have close interpersonal relationships and that also contribute to the ability to engage in employment or educational pursuits. Being married or cohabiting may also reflect the availability of a level of social support needed to engage in productive activity.

Variables related to social support also showed significant effects in the multivariate model. A marginal effect was noted for frequency of contact with members of the support network, and a curious negative effect was noted for encouragement for education. Why might participants who had more encouragement for education at baseline be less likely to engage in productive activity at follow-up? This finding might indicate that a participant received encouragement for education when enrolling in the program, which was time limited, but the encouragement may not have been sustained enough to support productive activity at follow-up. Frequency of social contacts, which predicted productive activity, may reflect the type of sustained support needed to engage in school or work. The counterintuitive finding might also reflect a reactive effect, in which a participant perceives a high level of encouragement as pushing, not helping. The encouragement would therefore have an effect opposite to the one intended. Alternatively, participants who received more encouragement may have been those who were less motivated and who thus required it.

Finally, two adjustment variables predicted later productive activity. Participants were more likely to engage in productive activity at follow-up if they reported more baseline problems in the housework domain and fewer problems in the financial domain. The finding about housework suggests that, as in the general population, having problems with or dissatisfaction about housework may motivate an individual to seek outside activities. The inability to do housework may indicate that a person's abilities lie elsewhere. On the other hand, having financial problems may represent barriers to productive activity, such as a lack of money for transportation or other expenses related to school or work.

Numerous variables were not related to productive activity, including most of the demographic variables, all self-perceptions, and variables related specifically to mental illness (diagnosis, symptoms, and length of illness). This finding supports Anthony's contention (

22) that rehabilitation potential reflects work-related characteristics, not mental-illness-related characteristics.

Self-perceptions are rarely tested in the literature on outcomes of vocational rehabilitation and were not found to be significant here. Perhaps, as Arns and Linney (

23) have suggested, self-perceptions are heavily founded on role status—that is, occupying meaningful roles in work or school. Consequently, measures of perceptions at follow-up may have been affected by the individual's participation and involvement in the rehabilitation intervention, rather than baseline self-perceptions affecting later productive activity.

Conclusions

The findings help us understand the relationship between mental illness and the ability to engage in productive activity, at least among those who participated in a supported education intervention. Critically important is that no demographic characteristics were associated with productive activity at follow-up and that specific characteristics of mental illness, such as diagnosis, symptoms, or length of illness, were not related to productive activity. This finding, however, is limited by the lack of complete data on diagnosis and other details of the illness; further research might attempt to collect more detailed data in this area, including hospitalization history.

Equally critical is that the factors found to be related to productive activity at follow-up—productive activity at baseline, financial resources, and social support—are likely to be important factors for nondisabled populations as well. In particular, among those with mental illness, social support is likely to be a key factor in attaining goals. Earlier attempts by these individuals to advance their education or employment may have been met with resistance by the system and by stigmatizing attitudes, resulting in frustration and failure to complete goals. The intervention itself is designed to provide support in addition to practice in skill building. The findings of this study suggest that supports outside the program are important to participants' engagement in productive activity.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the community support branch of the Center for Mental Health Services through grant HD5-SM47669 to the Michigan Department of Mental Health. The study represents a collaboration between the schools of social work at the University of Michigan, Eastern Michigan University, and Wayne State University, and the Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency.