Adults with mental retardation exhibit the same types of psychiatric disorders as adults of normal intelligence, although an accurate diagnosis is often difficult to make. Diagnostic overshadowing, for example, in which abnormal behaviors are assumed to be the result of mental retardation rather than potential comorbid psychopathology, may obscure identification of psychiatric conditions. An examination of specific types of disorders is needed for a more complete understanding of the clinical features of psychiatric disorders in persons of varying levels of intellectual impairment (

1).

In this study we focused on the co-occurrence of schizophrenia in persons with severe or profound mental retardation. Historically, dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and mental retardation has been a source of controversy (

2). Deficits in language ability may hamper or preclude self-reports of delusions, hallucinations, and other expressions of disordered thought that are the hallmark diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. Nonetheless, persons with mental retardation show the full range of psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (

3).

Our primary aim in this study was to provide a broad description of the symptoms of schizophrenia in a residential sample of adults with severe or profound mental retardation. We compared the lists of symptoms that led to psychiatric diagnoses of schizophrenia in this sample with the symptoms of schizophrenia that are characteristic of persons of normal intelligence, following the Lenzenweger and Dworkin four-factor structure of schizophrenia phenomenology (

4). Evidence showing similarity of symptoms may help in identifying common behavioral or physical signs of schizophrenia and may lead to the development of empirically based criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia in persons with severe or profound mental retardation.

Methods

Participants were 60 residents of a large developmental center in central Louisiana. All were classified as having severe or profound mental retardation (82 percent and 18 percent, respectively).

Twenty of the participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia that was obtained through the following protocol. A licensed psychologist was given information from the Diagnostic Assessment for the Severely Handicapped (DASH-II) (

5), other behavioral rating scales, social skills measures, and behavioral observations. After reviewing this information and the

DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, the psychologist decided whether the diagnosis of schizophrenia was warranted. A board-certified psychiatrist reviewed the information for those who met

DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia. If the psychiatrist and the psychologist considered the information sufficient to warrant the diagnosis, the diagnosis was given and became the diagnosis of record.

The sample was divided into three groups. Group 1 consisted of the 20 persons with a psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia, all of whom also had elevated scores on the schizophrenia subscale of the DASH-II. They had no psychiatric diagnoses other than schizophrenia. Group 2 consisted of 20 persons whose schizophrenia score on the DASH-II was similarly elevated but who did not warrant a psychiatric diagnosis of schizophrenia. Group 3, the control group, consisted of 20 persons with no significant elevations on any of the DASH-II subscales and no psychiatric diagnosis of any kind. We conducted a one-way analysis of variance of the frequency scores of the schizophrenia subscale. (Extensive information on the demographic and health characteristics of the sample as well as the method of administration, scoring, and psychometric properties of the DASH-II are available from the authors on request.)

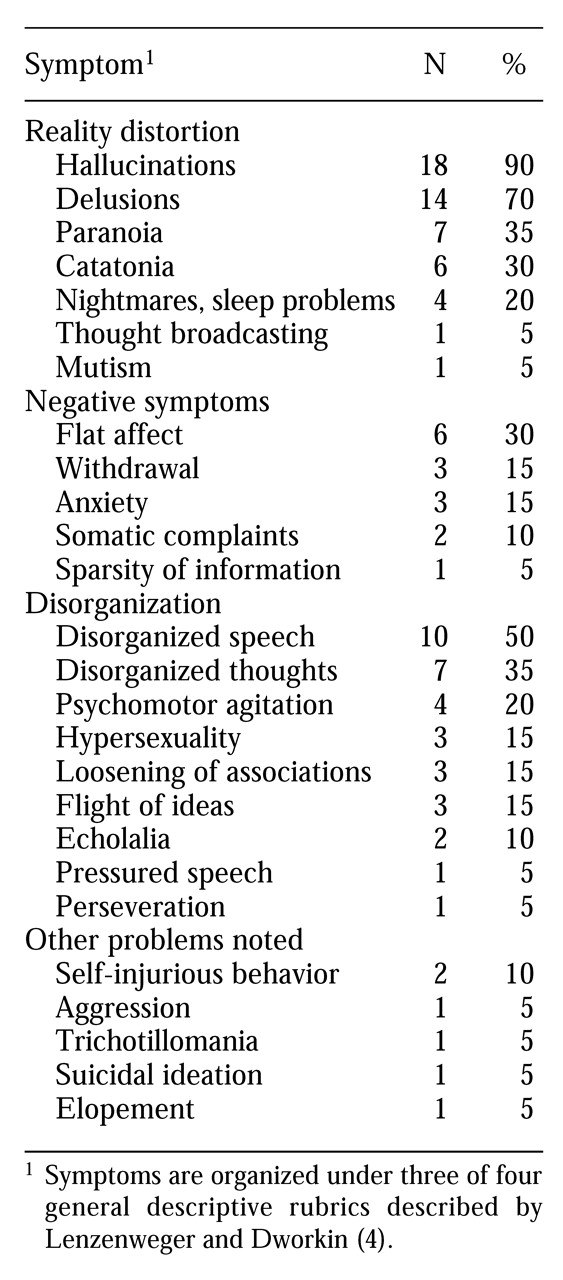

Next we conducted a frequency count of symptoms taken from the psychiatric reports of the subjects in group 1, those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and an elevated schizophrenia subscale on the DASH-II. We organized these symptoms according to three of the four factors of schizophrenia phenomenology described by Lenzenweger and Dworkin (

4)— reality distortion, negative symptoms, and disorganization; we omitted the fourth factor, premorbid social functioning, because the information for it was not available.

Results and discussion

A one-way analysis of variance of the frequency scores of the schizophrenia subscale showed that differences between the three groups were statistically significant (means were 5.11, 3.09, and .38 for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; F=73.41, df=2, 57, p> .001). Thus the groups were empirically distinguished on the frequency dimension of the DASH-II schizophrenia subscale.

As shown in

Table 1, most of the symptoms of schizophrenia in group 1 fell under the larger rubrics of reality distortion and disorganization. The most prevalent symptoms in the sample were hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, paranoia, and disorganized thinking. Negative symptoms occurred, but at a lower rate than those involving reality distortion or disorganization. Among negative symptoms, flat affect, withdrawal, and anxiety-related problems appeared most often. Other problems that did not fall under the three Lenzenweger and Dworkin categories included self-injurious behavior, aggression, and suicidal ideation.

As has been suggested in prior research on coexisting mild to moderate mental retardation and schizophrenia, persons with severe or profound mental retardation and schizophrenia exhibit a range of positive symptoms, in particular hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech (

3,

6). In this respect, the positive features of schizophrenia for persons with severe or profound mental retardation, at least in terms of frequency, resemble the clinical picture of schizophrenia without mental retardation (

7,

8).

Negative symptoms, however, were markedly underrepresented in this group. Diagnostic overshadowing may have influenced identification of negative symptoms such as flat affect and withdrawal. In this population the presence of mental retardation can decrease the significance of anomalous behaviors associated with psychopathology. Alternatively, the relative infrequency of negative symptoms may be an artifact of how symptom information was obtained. Because symptom information was drawn from psychiatric reports, there may have been a bias favoring overt behaviors, especially those disturbing or otherwise salient to staff. Thus it is possible that the frequency of negative symptoms among persons with severe or profound mental retardation in this study underestimates the true prevalence. Further research is necessary to replicate the pattern of outcomes we obtained for positive and negative symptoms with larger samples.

To shed light on the sensitivity of the DASH-II as a screening tool for schizophrenia in persons with severe or profound mental retardation, we examined the pattern of diagnoses in subjects in group 2, those whose score on the schizophrenia subscale of the DASH-II was elevated but who did not have a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Interestingly, the majority of group 2 met criteria for psychiatric disorders that either share clinical features with schizophrenia, such as psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, or have psychomotor features consistent with the neuroleptic side effects often seen among persons with schizophrenia, such as stereotypic movement disorder. Other diagnoses for those in group 2 included stereotypic movement disorder (40 percent), psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (30 percent), bipolar disorder (10 percent), anxiety disorder not otherwise specified (5 percent), or no diagnosis (15 percent).

Conclusions

The DASH-II identifies behaviors and symptoms that are consistent with schizophrenia, and thus it may be a useful screening tool for psychotic disorders in general. Given the instrument's relative lack of specificity for schizophrenia, it should be used in conjunction with other assessment instruments for diagnosing schizophrenia in persons with severe or profound mental retardation.

Much of the emphasis in research on the diagnosis of schizophrenia in persons with mental retardation, as in the area of schizophrenia in general, is on developing methods to improve our ability to make the diagnosis. However, schizophrenia is marked by great clinical heterogeneity, leading some to argue that the diagnosis itself should be abandoned and that we should concentrate on specific symptoms, such as hallucinations, rather than on general syndromes (

9). If this approach is adopted, then the DASH-II may be particularly useful clinically in identifying specific symptoms to be targeted for treatment.