There is a growing body of evidence, both clinical and theoretical, challenging the use of high-dose antipsychotic therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia (

1,

2,

3,

4,

5). The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate antipsychotic dosing in several settings to determine whether the recommendation of lower doses is being reflected in clinical practice.

Methods

The study was designed as a retrospective chart review and received the necessary science and ethics approval from the review boards at the three settings. Over a six-month interval in the latter half of 1997, charts were reviewed simultaneously in each of three treatment settings: a university-affiliated psychiatric teaching hospital with 85 beds and a large inpatient and outpatient schizophrenia research program; a general community hospital with 25 psychiatry beds; and a large provincial hospital with 325 beds devoted to outpatient care as well as long-term inpatient treatment of patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses, mostly schizophrenia.

Patients treated in the provincial hospital are drawn from the surrounding communities and are also referred from shorter-stay centers. Thus patients treated at this site may have been referred from one of the other two sites. Referrals routinely occur at an inpatient level and are driven by length-of-stay requirements that mandate transfer to the 325-bed provincial hospital.

For this study, outpatient psychiatrists who treated patients with chronic schizophrenia were identified at each setting. Eight were identified at the university-affiliated hospital, six at the community hospital, and 11 at the provincial hospital. At each site a list of charts of patients of the identified physicians was randomly compiled. The list was sequentially reviewed by the authors—three psychiatrists and a psychiatric nurse. The review included current and past medical records to ensure that the necessary inclusion criteria were met.

The review continued until an adequate sample was obtained at each site. The goal was to identify at least 50 charts in which the patients met several criteria. Patients had to be between the ages of 18 and 55 years, have a

DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia (

6), have outpatient status, and be stabilized for one month or longer on their antipsychotic medication. If these criteria were met, several additional measures were determined, including gender; age at onset of the disorder, measured as the first psychiatric contact; duration of illness; number of hospitalizations; and other psychotropic medications.

Analysis of variance was used to evaluate differences in dosage of antipsychotic medication between the groups from each treatment setting. Differences in age, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, and number of hospitalizations were also examined. When statistically significant differences were observed, a Scheffé F test was used for post hoc comparisons. Contingency tables employing chi square tests were used to evaluate differences between the three treatment settings in gender, number of antipsychotic medications, type of antipsychotic (conventional versus novel), antipsychotic formulation (oral versus depot), number of other psychotropic medications, and use of antiparkinsonian medication.

To facilitate comparisons, antipsychotic dosages were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents (

7). For example, the following dosages were equivalent: haloperidol 2 mg, trifluoperazine 5 mg, thioridazine 100 mg, risperidone 2.5 mg, and olanzapine 10 mg.

Results

At the university-affiliated hospital, 126 charts were reviewed, and 52 met the criteria. At the community hospital, 113 charts were reviewed, and 53 met the criteria. At the provincial hospital, 112 charts were reviewed, and 58 met the criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion were a diagnosis other than schizophrenia and lack of stabilization on antipsychotic medication.

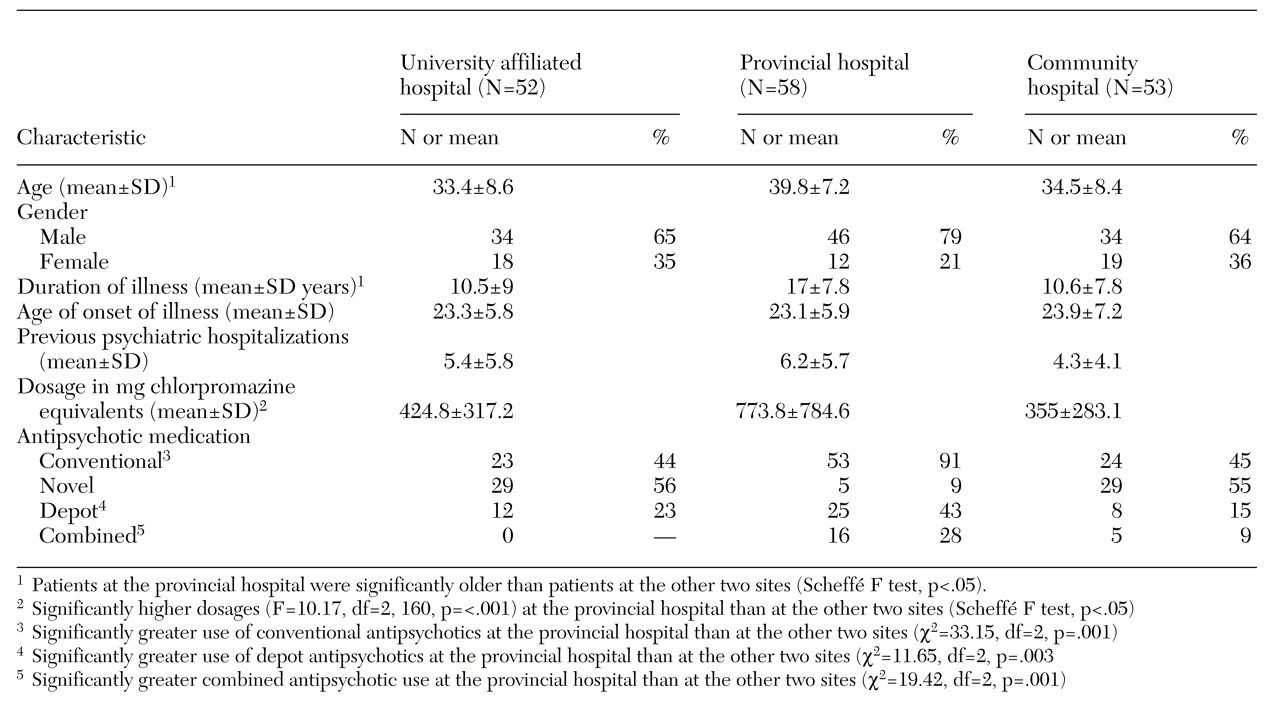

Results are summarized in

Table 1. The majority of patients at all sites were male. Patients in the provincial hospital were significantly older and had been ill for a significantly longer time. Patients in the provincial hospital received significantly higher dosages of antipsychotic medications than those at the university-affiliated hospital and the community hospital. At the provincial hospital, we found greater use of conventional antipsychotics and depot antipsychotics and greater concomitant use of two antipsychotics. In addition, more patients in the provincial hospital received antiparkinsonian medications.

Discussion

It has been suggested that in maintenance antipsychotic therapy, the optimal dosage range is 300 to 600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents daily (

2). In this study the mean dosage at the university-affiliated hospital and the community hospital was within this range. Earlier data indicated substantially higher dosages in these settings (

8), and the same trend has been reported elsewhere (

9).

Several factors may account for the finding of higher dosages at the provincial hospital. Severity of illness may be an important factor, as both the university-affiliated hospital and the community hospital transfer patients to the provincial hospital if they are doing poorly and if it appears that long-term inpatient treatment will be required. Patients in the provincial hospital sample were older and had been ill longer.

Another factor, very likely related, is the pattern of antipsychotic use. Significantly fewer patients in the provincial hospital were being treated with novel antipsychotics. Although the dosages of novel antipsychotics and conventional antipsychotics were not significantly different (423.8 mg and 582.8 mg chlorpromazine equivalents daily, respectively), a trend was found toward lower doses of novel antipsychotics (p=.08).

No patient was receiving three antipsychotics simultaneously, but more than 25 percent of the provincial hospital patients were receiving two antipsychotics, compared with 9 percent at the community hospital and none at the university-affiliated hospital. Of the 21 patients in the entire sample who were taking two antipsychotics, the mean±SD total dosage was 1,075.1±844.6 mg chlorpromazine equivalents daily.

Of particular note was the finding of a significant difference in mean dosage—1,258.3±921 mg (range, 371 to 4,079 mg) at the provincial hospital and 617.0±355 mg (range, 336 to 1,149 mg) at the community hospital (t=1.64, df=19, p=.05). At the provincial hospital, the mean dosage of antipsychotic medication, excluding the patients on two antipsychotics, was 608.3±670.7 mg per day.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective design. Because of the design, it was not possible to distinguish the patients by severity of illness or to identify precisely why certain treatment approaches were undertaken. The sample may have included patients who were placed on higher dosages of antipsychotics at a time when this practice was more acceptable. Although some clinicians may now adhere to a low-dose approach, they may find it difficult to taper the antipsychotic dosage for patients who have been taking high doses for a number of years. Finally, conversion formulas, particularly for depot antipsychotics, are not well established, a point of particular relevance at the provincial hospital, where significantly more patients were receiving depot medications.

Conclusions

It would appear that clinical settings, both academic and nonacademic, are paying heed to the guidelines advocating lower dosages of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. However, at one site in this study, evidence was found that dosages exceeding the current recommendations continue to be used. The use of higher dosages was reflected in a different pattern of antipsychotic use, such as the use of more than one medication. Such practice may well represent a different patient population—patients who are more ill or who have been ill longer. Nevertheless, we are still faced with the growing body of evidence that higher dosages of antipsychotic medications are not more effective and raise the risk of side effects.