Deinstitutionalization was intended to improve the lives of persons with serious and persistent mental illness by replacing institutional care with community-based services (

1). However, evidence suggests that failure of the system to provide even the most basic services—for example, housing—has contributed to higher rates of homelessness and frequent hospitalization among this population (

2,

3,

4,

5). Although the extent to which psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial stressors, and poverty contribute to these problems is unknown, it is clear that the need for comprehensive, community-based services that make community living possible is not met (

5,

6,

7).

Over the past several decades, residential crisis facilities have developed as a potentially less costly and less restrictive alternative to psychiatric hospitalization (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12), and a wide variety of treatment programs have evolved within this approach (

13,

14,

15,

16). One example is the emergency housing program, which is designed to provide temporary housing, case management, 24-hour supervision, and linkage to community-based psychiatric services to persons experiencing acute episodes of psychiatric symptoms.

As a step-up program from community-based living, emergency housing can provide residents with more structure and safety during times of crisis. As a step-down program from inpatient treatment, it can facilitate the transition from inpatient to independent community-based living by providing time to address the complex needs of persons with severe mental illness before their release.

The need for programs of this sort has grown in recent years, partly as a result of the decreasing length of inpatient stays and reduced availability of inpatient beds, particularly in state-operated facilities (

16). Several studies indicate that temporary supportive housing facilities can serve as an alternative to inpatient treatment (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13), but there is disagreement over whether less restrictive alternatives to hospitalization can adequately provide the care and structure offered by an inpatient unit (

17,

18). Still, inpatient care is not accessible within the current health care system for all who seek it or could benefit from it (

16); therefore, efficient alternatives are needed.

The goals of the study reported here were to evaluate the effectiveness of emergency housing programs and to determine their utility and feasibility as an alternative to inpatient treatment for persons with serious and persistent mental illness.

Methods

Subjects

Data were obtained in July 1995 through a retrospective chart review of all 161 persons admitted consecutively to the emergency housing program at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago between November 1993 and October 1994. For persons with multiple admissions during this period, only the first admission was included. The emergency housing program is a transitional supportive housing program. It has 25 beds and houses men and women age 18 to 75 for one to three months.

Measures

Three measures were used to collect and assess data: the program's own service evaluation study questionnaire, the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) scale, and the Acuity of Psychiatric Illness (API) scale (

19).

The service evaluation questionnaire was used to obtain the residents' demographic characteristics, along with housing and funding status and linkage to psychiatric treatment at admission to and discharge from the program. Information about funding status was also obtained by reviewing medical charts, which included hospital records on billing documentation and public assistance records.

The SPI scale was developed to help predict utilization of services in acute care facilities. It can be used either prospectively or retrospectively with comparable reliability and validity (

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28). In this study, it was used retrospectively through medical chart review. Three SPI indexes—suicide potential, danger to others, and severity of psychiatric symptoms—used together have been shown to be a valid predictor of the decision to hospitalize by emergency room personnel (

20). A patient's scores for the three indexes are used in a formula to compute an overall probability of admission score (

23).

The API scale is used to evaluate the levels of clinical change (clinical status) and service need (nursing status) during the use of acute psychiatric services (

28). The API scale has been shown to be a reliable and valid outcome measure in crisis settings in both prospective and retrospective applications (

19,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28). As was the SPI scale, it was used retrospectively in this study.

Procedure

The chart reviewers were graduate students who had participated in training sessions for the API and SPI scales. To establish interrater reliability, each reviewer rated the same five charts, and 25 percent of all charts were reviewed by one of the reviewers as well as an independent reviewer. Kappa reliability was .86 for the SPI and the API across all of the raters.

On admission to and discharge from the emergency housing program, residents were evaluated using all three measures. For the analyses described below, residents were assigned to one of three groups. Residents who had been admitted to the program directly from an inpatient unit were designated as the step-down group. Residents who had been referred by a community service provider were divided into two groups, designated as step-up groups, according to whether their SPI scores indicated that they did or did not meet criteria for hospital admission.

Data analyses

Analyses of covariance were used to evaluate the change in API scores between admission and discharge within and across the three groups. For the first set of analyses, the independent variable was step-up status. Covariates were the clinical API, nursing API, and total API scores on admission to the emergency housing program; the dependent variables were the same scores at discharge.

The second set of analyses included only residents in the two step-up groups; the independent variable was whether or not the residents met hospitalization criteria. Again, the covariates were the three API scores at admission, and the dependent variables were the scores at discharge. Finally, the same method was used to compare dispositional and supportive outcomes between the three groups. The two dispositional outcomes were defined as hospitalization at discharge and whether discharge from the emergency housing program was or was not according to treatment plan; the supportive outcome was funding at discharge.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The mean±SD age of the 161 residents was 37.5±11.2 years. Most of the residents were male (103, or 64 percent). Ninety-one were Caucasian (57 percent), 63 were African American (39 percent), and five were Hispanic (3 percent). The majority of residents had never been married (111, or 69 percent), 41 were divorced or separated (25 percent), four were married (3 percent), and two were widowed (1 percent). No significant demographic differences were found between the three groups.

Clinical and psychosocial outcomes

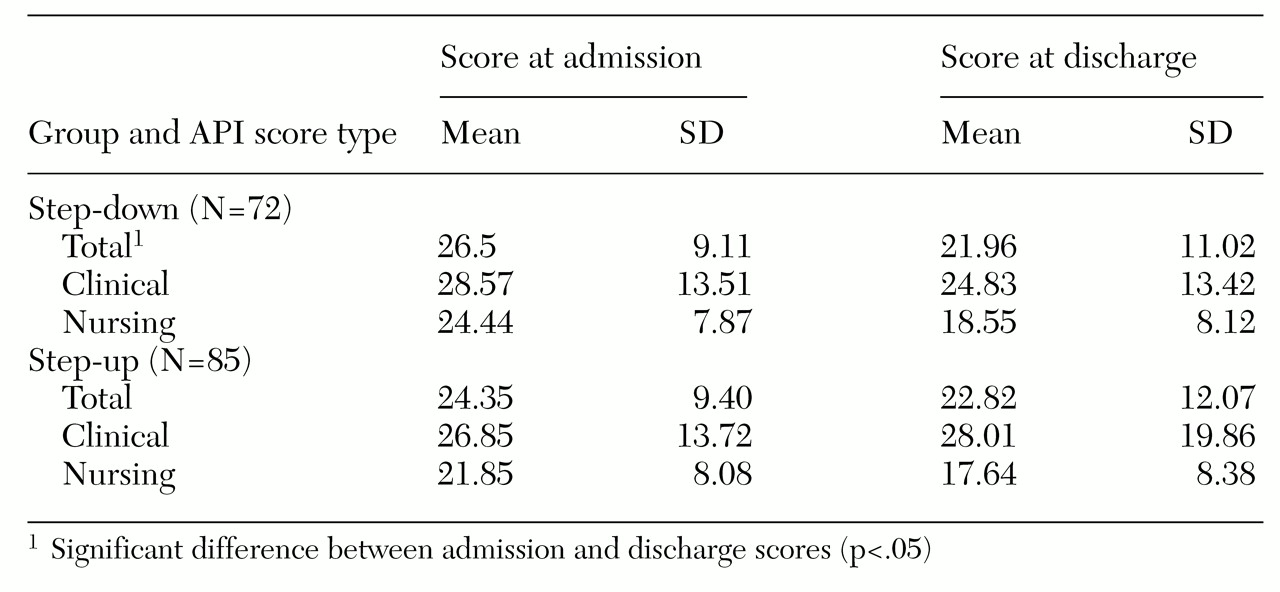

Residents in the step-down group showed significant improvement in clinical outcomes at discharge, as indicated by their API scores (

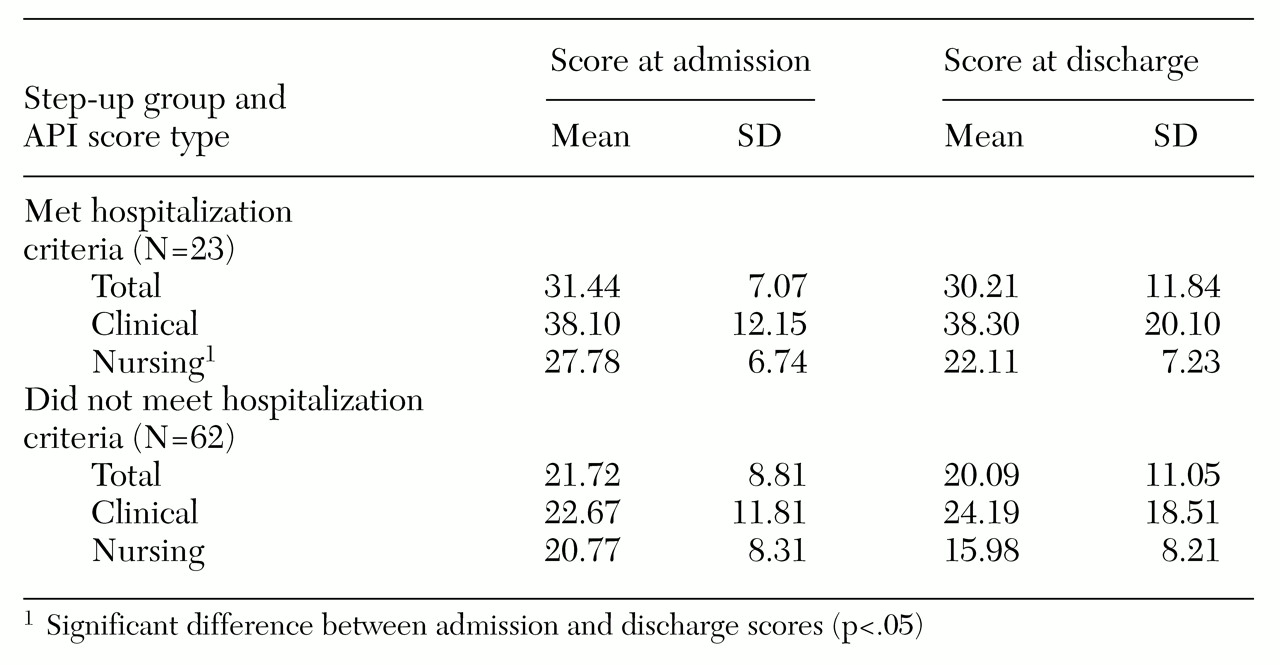

Table 1). Residents in both step-up groups also improved on API scores between admission and discharge (

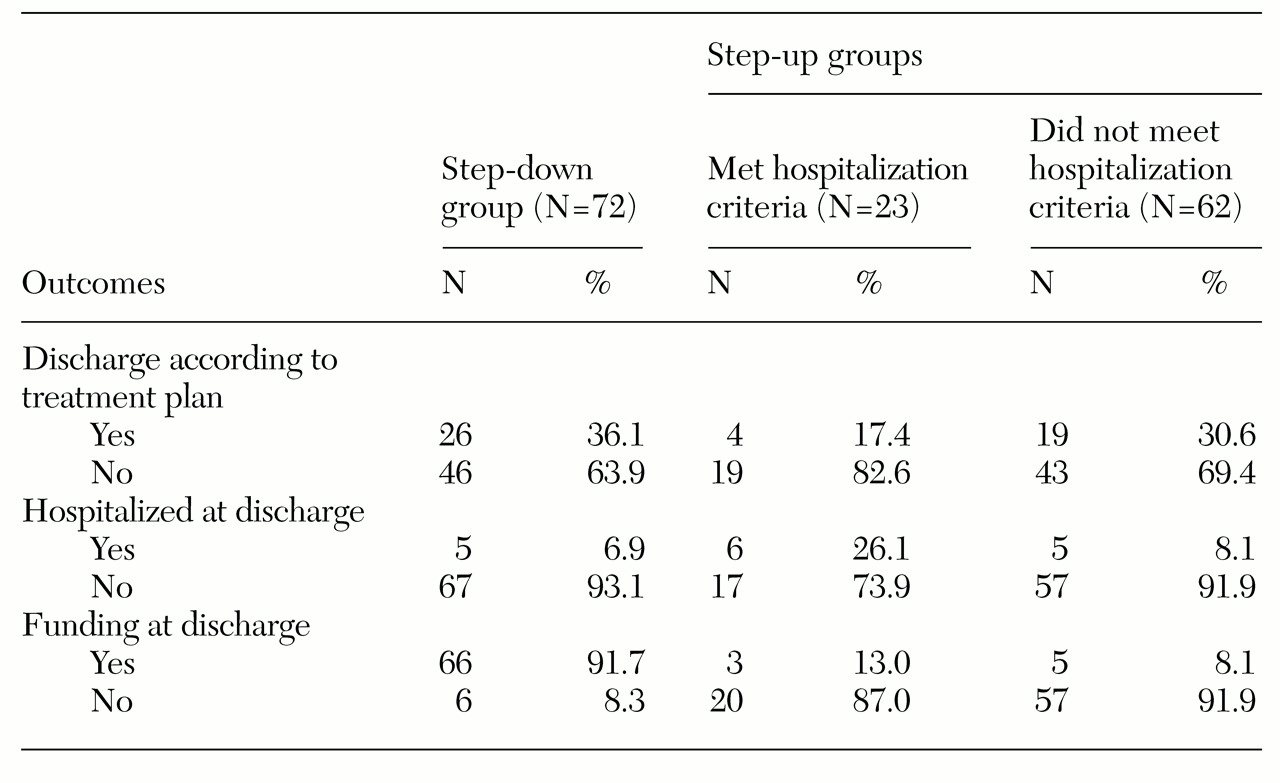

Table 2), although the changes were not statistically significant. All residents showed improvement between admission and discharge in scores on need for hospitalization and—with the exception of step-down residents—for funding at discharge, although these changes were not statistically significant (

Table 3).

Discussion and conclusions

The findings presented here suggest that emergency housing programs can serve as an effective form of alternative residential care for many people with serious and persistent mental illness. The clinical outcomes for the residents in all three groups in our study were relatively comparable to the outcomes of similar studies that assessed the effectiveness of residential alternatives to inpatient care (

11,

12).

Our results suggest that emergency housing is somewhat more effective as a step-down program from inpatient treatment than as a step-up program from community-based living. It may be that a short inpatient stay before entry into an emergency housing program facilitates more significant clinical benefits, affording step-down residents a head start in the recovery process. Certain unique features of inpatient treatment, such as the high level of security or intensive medication management, may contribute to more rapid clinical improvement, even after discharge.

Further investigation into the aspects of inpatient treatment that are most strongly associated with clinical improvement may be useful in identifying features that are unique and clinically efficacious and distinguishing them from those that can be delivered in an alternative setting such as emergency housing. Also, efforts to more specifically identify and address the needs of residents who are referred to more intensive programs may improve program effectiveness.

Although the residents who were referred from community-based living and met criteria for hospital admission did not show statistically significant improvement on outcome measures, the direction of change in scores was positive. It did not appear to matter whether a person admitted directly from the community met the clinical criteria for psychiatric hospitalization. These results suggest that about 75 percent of persons in this study who avoided hospital admission by entering the emergency housing program (as shown in

Table 3) were able to use the program as an effective alternative to hospitalization.

Interestingly, residents who met criteria for hospital admission exhibited a significant improvement in nursing scores, which may indicate a need for care that is not strictly clinical. Supportive care provided as a nontreatment aspect of inpatient treatment, such as housing, food, and security, may be an integral part of the recovery process during stages of acute illness. Fulfillment of many of these needs in a longer-term, less-structured environment such as an emergency housing program may be feasible and helpful in initiating a therapeutic process when inpatient care is limited or unavailable.

Our study had several shortcomings. First, raters were not blinded to the step-up or step-down status of the residents. Second, we lack information about the residents' psychiatric status and psychosocial functioning after discharge from the emergency housing program. Long-term follow-up data could help illustrate whether emergency housing programs effectively facilitate a stable transition into long-term community living and whether clinical improvements are enduring or transient. Finally, the generalizability of our findings to other crisis residential programs may be limited because of programmatic differences.

Future studies to compare the course of illness and community tenure among persons who receive only inpatient treatment and those treated only in emergency housing programs would help determine the relative efficiency as well as the effectiveness of this alternative to inpatient care. In addition, investigations focusing on overall costs of mental health expenditures in service systems that use an emergency housing program in conjunction with, and as an alternative to, inpatient treatment would facilitate a direct evaluation of cost-effectiveness. Because history of inpatient treatment is a strong predictor of hospitalization (

29), use of alternative forms of care such as emergency housing programs to avoid hospitalization altogether might be an important avenue to explore.