Discussion and conclusions

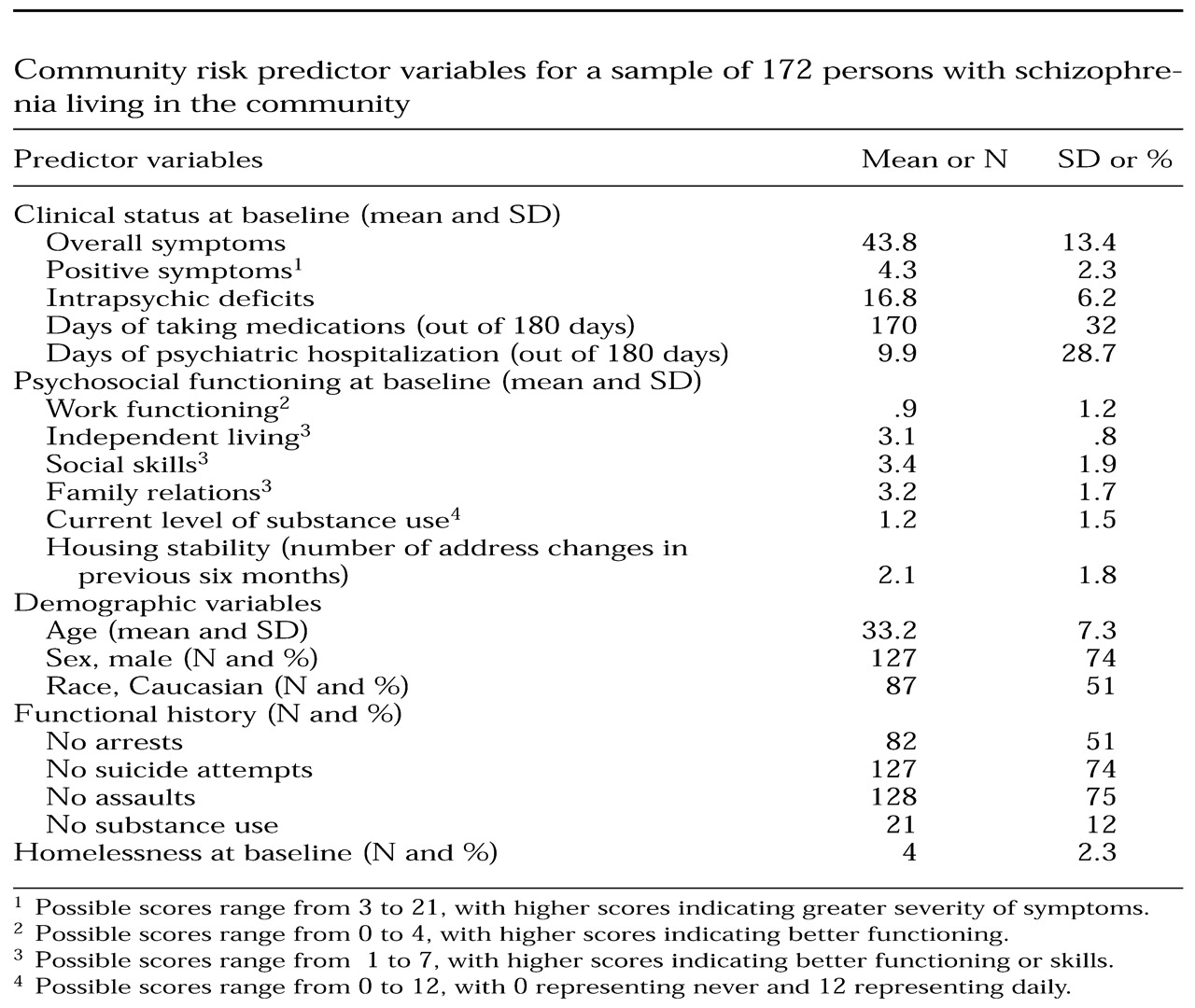

This study examined the self-reported rates of police contact, criminal charges, and victimization over a three-year period among individuals with diagnoses of schizophrenia who were living in a major urban community in the United States. At baseline these individuals were housed in their community, did not have co-occurring substance use disorders, and were in a nonacute phase of their disorder. With these baseline characteristics, this sample could be considered to be more stable and at a lower risk than samples in most previous studies of community risk among individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Because this was a prospective study, we were also able to use a comprehensive set of baseline variables to predict future community risk.

In examining these data, it is important to distinguish risk to the community—represented by police contact and criminal charges—and risk from the community—represented by victimization. Police contact and criminal charges are costly (

15) and can threaten the well-being of the general community (

4). High rates of police contact can also be seen as an indication that the police are serving a mental health function in the community (

13).

We found high rates of police contact in our sample: nearly 50 percent of the participants had police contact at least once during the three years, and the annual rate was 16 percent to 19.3 percent. Eighty-four percent of the police contact was initiated by someone other than the participant. A minority of the contacts were related to behavior against persons or property.

It is difficult to compare the data from this sample with national population data because of reporting differences in the databases. However, the annual rate of face-to-face contact with the police for somewhat comparable events was about 7 to 8 percent of the U.S. population in 1996, one of the first years that national data were gathered (

43). Fifty-four percent of the police contact in the national sample was initiated by someone other than the subject. Compared with a national public sample, individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community have more than twice as much contact with the police, and far more of this contact is initiated by someone else, including the police. It is not clear why the police have this rate of involvement, but the kind of contact is most likely to be related to behavior that is not violent or threatening to property.

Only one previous study of persons with serious mental illness who were participating in community-based treatment—in Madison, Wisconsin—produced comparable data on police contact. In that study, 38 percent of the sample had police contact unrelated to victimization in a 12-month period (

16). This rate is considerably higher than the rate in our sample. It is possible that the community context is important here: Madison is a much smaller city and has well-developed assertive outreach programs that strive to keep individuals with schizophrenia in the community. These conditions could increase the likelihood of police interaction with persons who have mental illness.

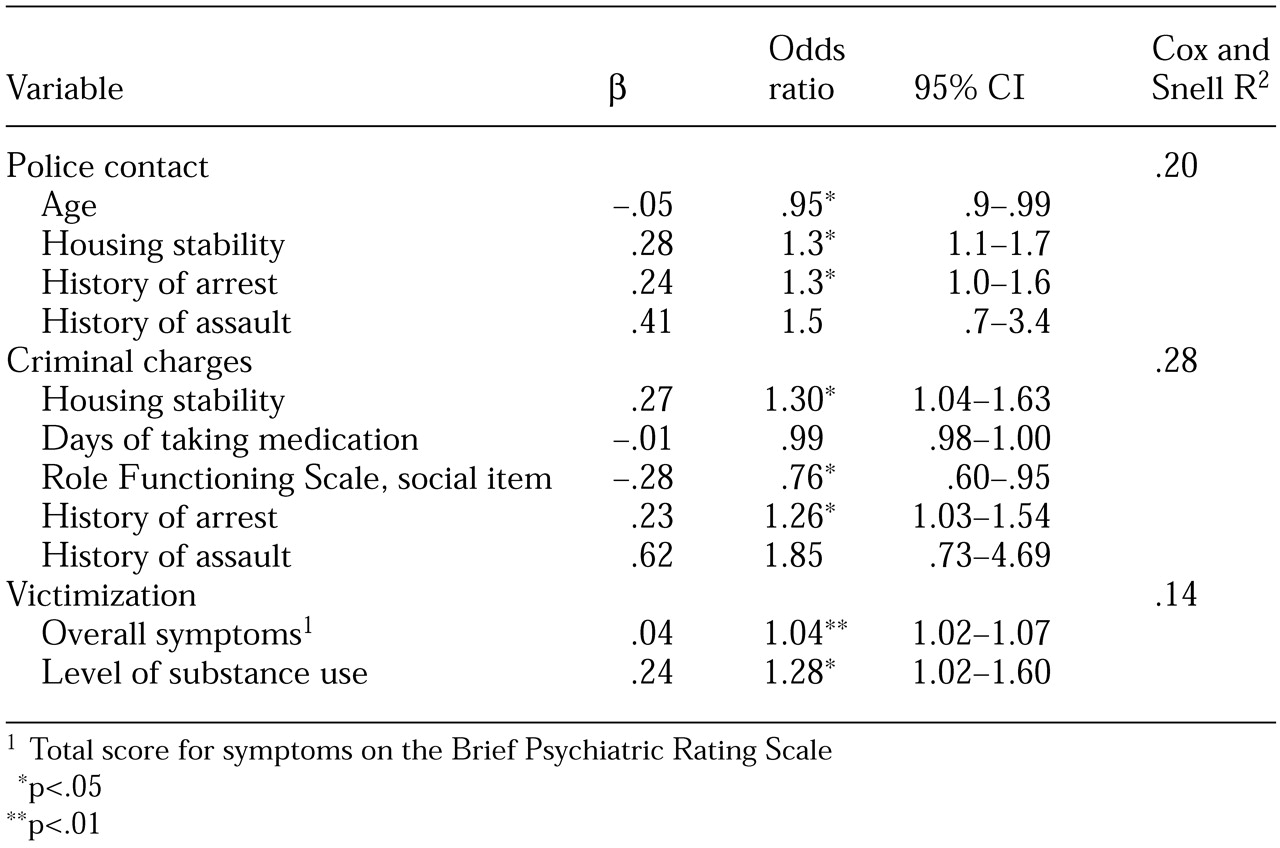

The predictors of police contact in our study were younger age, more address changes, and a history of arrest or assault. This pattern suggests that younger, more transient individuals with histories of assault and previous contact with the police are more likely to have contact with the police in the future. It is difficult to compare these findings with those from previous studies for several reasons—for example, one study did not distinguish between victim and nonvictim police contact—but having an unstable housing situation and being younger were consistent predictors across studies and samples. Substance abuse and a history of arrest or assault were also predictive of police contact.

Twenty-two percent of our sample had charges filed against them during the three-year study period. This finding suggests that fewer than half of the police contacts resulted in charges being filed. The yearly arrest rate in our sample was 7.2 to 8.7 percent. The arrest rate in Los Angeles in 1993 was 5.6 percent of the adult population (

44). Fewer than 30 percent of the charges involved behavior against persons or property; the vast majority of charges involved status offenses or traffic-related offenses. Only 2.3 percent of the total sample reported having been charged for behavior against a person during the three years; the yearly rate was .8 to .93 percent. The annual arrest rate for comparable crimes in Los Angeles in 1993 was 1.3 percent (

44).

Two previous studies of persons with severe mental illness found higher arrest rates than ours, although these studies are not directly comparable with ours. Wolf and associates (

16) reported a rate of 28 percent for a 12-month period, but in their study arrests and incarcerations were combined. Clark and colleagues (

15) reported a rate of 44 percent for a three-year period, but their sample had dual diagnoses of a major mental disorder and a substance use disorder. The arrest rate in our sample was similar to that reported by Harry and Steadman (

18), who used a diagnostically heterogeneous group of inpatients and outpatients in a rural area of Missouri and included arrest data from 1975 and 1983.

In our study, poorer social functioning, more address changes, fewer days of taking medication, and a history of arrests or assaults were predictive of a criminal charge. This finding suggests that compared with individuals who have had police contact only, those who have been charged by the police are more seriously debilitated and less compliant with treatment, although both groups have unstable living situations and have histories of acting out and police contact.

Taken together, the first two indicators of risk to the community—police contact and criminal charges—suggest that the police have extensive contact with persons in the community who have schizophrenia but that most of this police involvement (70 percent) concerns behavior such as traffic offenses, jaywalking, and police-assistance calls, not offenses against property or persons. Less than half of the police contact resulted in charges being filed. The arrest rate was about 45 percent higher than that among the general public, but the arrest rate for violent crimes was almost 40 percent lower than among the general public.

As for the predictors of police involvement, more serious involvement—for example, criminal charges as opposed to mere contact with the police—was associated with more compromised functioning. In fact, the police had the most intensive interaction with individuals who had the greatest mental health needs. Thus the challenges and risks that these individuals pose to the police increase as the police interact more intensively with more debilitated individuals with schizophrenia. Without adequate training for the police officers who interact with persons with serious mental illness, there is also a greater risk to the ill individuals themselves. This elevated risk suggests the importance of specialized police training in serious mental illness and the need for more community-based real-time crisis assistance to police officers from specialized mental health care providers.

When these results are combined with the results of previous studies of seriously mentally ill persons in the community, it is clear that a great deal of the risk that individuals who have schizophrenia pose to the community comes from conditions that coexist with schizophrenia, such as substance use and homelessness. Nonetheless, younger age, fewer days of taking medications, a more unstable housing situation, poorer social functioning, and a history of police involvement were associated with a greater likelihood of police contact or arrest. This information should guide service providers in their assessments and planning for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community.

Thirty-eight percent of our sample reported having been the victim of a crime during the study period. This represents an annual rate of 12.7 to 17.7 percent. The rate in Los Angeles was 7.7 percent in 1993 (

44). In our sample, 91 percent of the victimization was of a violent nature, which corresponds with an annual rate of violent victimization of 11.3 to 14.5 percent. The annual rate of violent victimization in Los Angeles in 1998 was 6.5 percent of the population (

43).

In our sample, 59 percent of victimization was not reported to the police, which is comparable to the rate of about 58 percent in the general population (

43). Individuals who have schizophrenia and who are living in the community have a victimization rate 65 to 130 percent higher than that of the general public. The rate of violent victimization was 75 to 120 percent higher among individuals with schizophrenia than among the general public. Some previous studies found considerably higher rates of victimization, but those studies targeted individuals who were homeless, had dual diagnoses, or were severely ill (

26,

28).

As for the predictors of victimization, being more symptomatic and having greater substance use at baseline were related to higher rates of victimization, and the severity of symptoms was the strongest predictor. This finding suggests that the most ill and vulnerable persons with schizophrenia are the most likely to be victimized. Substance use could compound their vulnerability by making them less able to fend for themselves and could expose them to exploitation by others. Given that six out of ten crimes are not reported to the police, it is possible that these individuals do not believe that the police will handle their situations adequately; however, this rate is nearly identical to the rate of nonreporting among the general public. Thus we have a highly vulnerable group that is victimized at high rates, and they generally do not seek protection from the police or the justice system.

In considering the results on community risk as a whole, it is apparent that there is substantial risk associated with schizophrenic individuals residing in the community. However, the overall risk is not due to the dangerous behavior of the ill individuals but rather to the high rates of contact that these individuals have with the police and to their high rates of victimization. The victimization of persons with schizophrenia is generally violent, involves the most vulnerable members of this group, and is usually not reported. Individuals in the community who have schizophrenia are at least 14 times more likely to be a victim of a violent crime than to be arrested for one. These individuals are more likely to be arrested than members of the general public, but such an arrest is less likely to be for a violent crime than is the case among the general public.

On the basis of these results, it is clear that for these individuals with schizophrenia the risk associated with being in the community was higher than the risk they posed to the community. This finding suggests a challenge to policy makers and service providers. Clearly, there must be greater interaction between the mental health sector and law-enforcement agencies. Police officers need education and training about mental illness as well as community-based crisis assistance from trained mental health providers when they deal with persons who have mental illnesses.

Three other aspects of these results deserve comment. The severity of symptoms at baseline was not related to subsequent police contact or to criminal charges being filed, which agrees with the findings of Monahan and colleagues (

45). In this regard, some studies have found that threatening and violent behavior among mentally ill individuals was related to active psychotic symptoms (

4,

46). Because ours was a sample of individuals with nonacute illness and extremely low rates of active psychotic symptoms at baseline, it is understandable that the severity of symptoms at baseline was unrelated to risk to the community. In the study by Monahan and colleagues, only 17 percent of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and the baseline severity of psychotic symptoms was not reported. Thus the discrepancy in findings related to active psychotic symptoms across studies could be related to a low severity of symptoms at baseline or to the timing of the clinical assessments relative to that of the risk behavior.

Second, other studies showed that race was related to both police contact and criminal charges. Ours was a multiethnic sample in an ethnically diverse community with a multiethnic police force, which could have limited the influence of race on the rates of police contact. Third, several of the baseline predictors we used are dynamic and would be expected to change over the three-year study period—for example, housing stability and medication use. We did not examine the relationships between such changes and whether they influenced the occurrence of community risk incidents. Although such analyses could have provided information about causal relations, they would not have resulted in the same kind of prospective predictive models that we generated.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not use a random sample. Thus we do not know how generalizable these results are to the overall population of persons with schizophrenia who are living in the community. However, as we have stated, our subjects were housed, did not have diagnoses of a co-occurring substance use disorder, and generally were compliant with medication. Second, Department of Justice or criminologic analyses were not taken into account when the data elements were designed. Thus the comparability of these data with other important public data sources is limited. Third, the use of arrest data from any source will underestimate the rates of violence in any population. Thus, although our study provided good estimates of arrest rates, this information clearly underestimates the rates of violent behavior in our sample. Finally, the findings are based on self-report data; however, as we have shown, this approach yields the highest single-source estimates of crime and violence in this population, and the rates are similar to those derived by triangulating multiple sources.

The results of this study have several implications for further research. Community risk should be measured by using data elements that are common to research on these topics. This approach would allow more adequate comparisons across databases and populations. Because random samples of individuals with schizophrenia are rare, the homogeneity of a study sample is not a problem as long as the sample is well described. It is then possible to compare community risk across samples that vary in important characteristics. Prospective studies are needed to examine changes in community risk as individuals make the transition out of homelessness and from substance abuse to recovery.