Consumer satisfaction is an important outcome measure of child mental health service delivery. With relative ease, child psychiatrists can document consumer satisfaction and use it as a measure of quality of service delivery for regulatory agencies and insurance companies. This study illuminates a number of methodological and conceptual issues in measuring consumer satisfaction in a children's psychiatric inpatient setting.

Young and colleagues (

1) have reviewed the studies on outpatient child mental health consumer satisfaction surveys. Methodological problems identified by Young and other investigators include potential sampling bias because of a low response rate (

1,

2,

3,

4); the increased complexity of child surveys compared with adult surveys (

1,

4,

5), since both patients and their parents must be surveyed; and cognitive immaturity of child patients (

1,

4,

6). They also found a dearth of psychometric data on the instruments used in consumer satisfaction surveys (

1,

2,

3,

6,

7).

In the only published study that we found of consumer satisfaction with child psychiatric inpatient services (

12), the parents and therapists of 42 child psychiatric inpatients were interviewed four to 17 months after the patients had been discharged from a ten-bed acute psychiatric unit in a pediatric hospital. Seventy percent of the parents reported that the treatment in the hospital had been "very helpful"; six percent found it "very unhelpful." Only the parents were interviewed, and there was no attempt to study the psychometrics of the interview instrument.

One goal of our study was to assess the overall satisfaction of patients in a child psychiatric inpatient hospital and their parents. Another goal was to examine the relationship between consumer satisfaction and parents' and children's perception of improvement in the problem that had led to hospitalization. We hypothesized that the greater the perception that the problem had been resolved, the greater the satisfaction.

Methods

Subjects

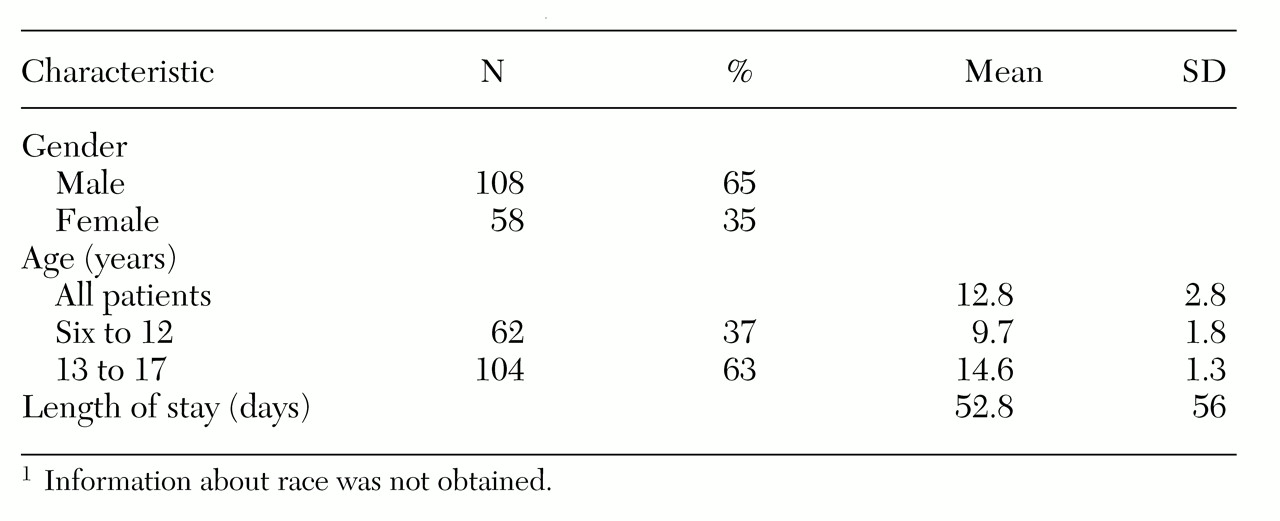

Of the 175 patients contacted, 166 (95 percent) agreed to be interviewed. A parent or caretaker was available for 114 of the 166 patients (67 percent), and of those, 111 (97 percent) agreed to participate in the study. The patients were unselected consecutive child psychiatric inpatients at an 80-bed freestanding state children's psychiatric hospital in New York. The patients' characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

Instrument

We developed a four-section, 28-item questionnaire to cover our areas of interest. All ratings were made on 5-point Likert-type scales. In the first section, respondents made an overall evaluation of the extent to which the primary problem—the diagnosis primarily responsible for hospitalization—changed as a result of treatment at the hospital. In sections 2 and 3, respondents rated their satisfaction with treatment experiences and other characteristics of the hospital—for example, types of therapy, medications, activities, staff, and the physical plant. The fourth section used a yes-or-no format to inquire about abuse of patients by the staff and drug use by any staff member or patient at the hospital. For children younger than 13 years of age, several of the items employed a smiling face or frowning face format rather than a numeric format. Parents made a final overall evaluation of the likelihood that they would return to the facility if their child needed to be hospitalized again.

Procedure

Three waves of patients and parents were sampled, from March to April 1994, May to July 1995, and October to December 1995. A target sample of 50 patients was set for each wave. Patients were contacted by a social worker within two weeks preceding their discharge and asked to answer a questionnaire concerning satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the hospital. Consecutive patients were contacted until the target sample number was met. The total number of patients surveyed slightly exceeded the target number for all three waves, for a total of 166. The questionnaires were completed in the presence of a social worker, who was available to answer any questions.

Data analysis

To reduce the number of variables and to create conceptually meaningful composite scores for analysis, the multiple items measuring satisfaction (sections 2 and 3 of the questionnaire) were first subjected to principal components analysis, for child and parent responses separately. For each analysis, principal components were extracted, and factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 were rotated with a Varimax rotation.

Factor scores were then calculated for each factor by using the regression approach. This approach weights standardized versions of the original variables by the factor coefficients to yield a single factor score for each case for each factor. When combined with principal components analysis, the regression method yields factor score distributions with means of 0 and standard deviations of 1.

Multiple regression was then used to predict overall evaluation ratings from the satisfaction factor scores. A standard regression procedure was used whereby all predictors were entered into the regression equation simultaneously. Entry into the equation required a given predictor to explain a significant proportion of the variance remaining after the variance explained by all other variables in the model was accounted for.

The equation was first evaluated for its ability to explain a significant amount of variance in the criterion, as determined by R2. For equations with a significant R2, individual predictors were evaluated by examining the standardized beta weights associated with each. Weights significantly greater than zero—as determined by a t test—were considered significant predictors.

Residual analysis was conducted to evaluate violations of assumptions. When serious assumption violations occurred, logistic regression was used on dichotomized criterion variables, with the odds ratio as the effect size indicator.

Data were analyzed for differences between the three sampling wave groups as well as between parents and children, between children aged 13 years and older and other participants, and between children aged 12 years and younger and other participants. Because no differences were found between the sampling wave groups or between the children's groups, we were able to collapse the sampling wave groups into one and the children's age groups into one. Thus we retained parents and children of all ages as the two grouping categories.

Results

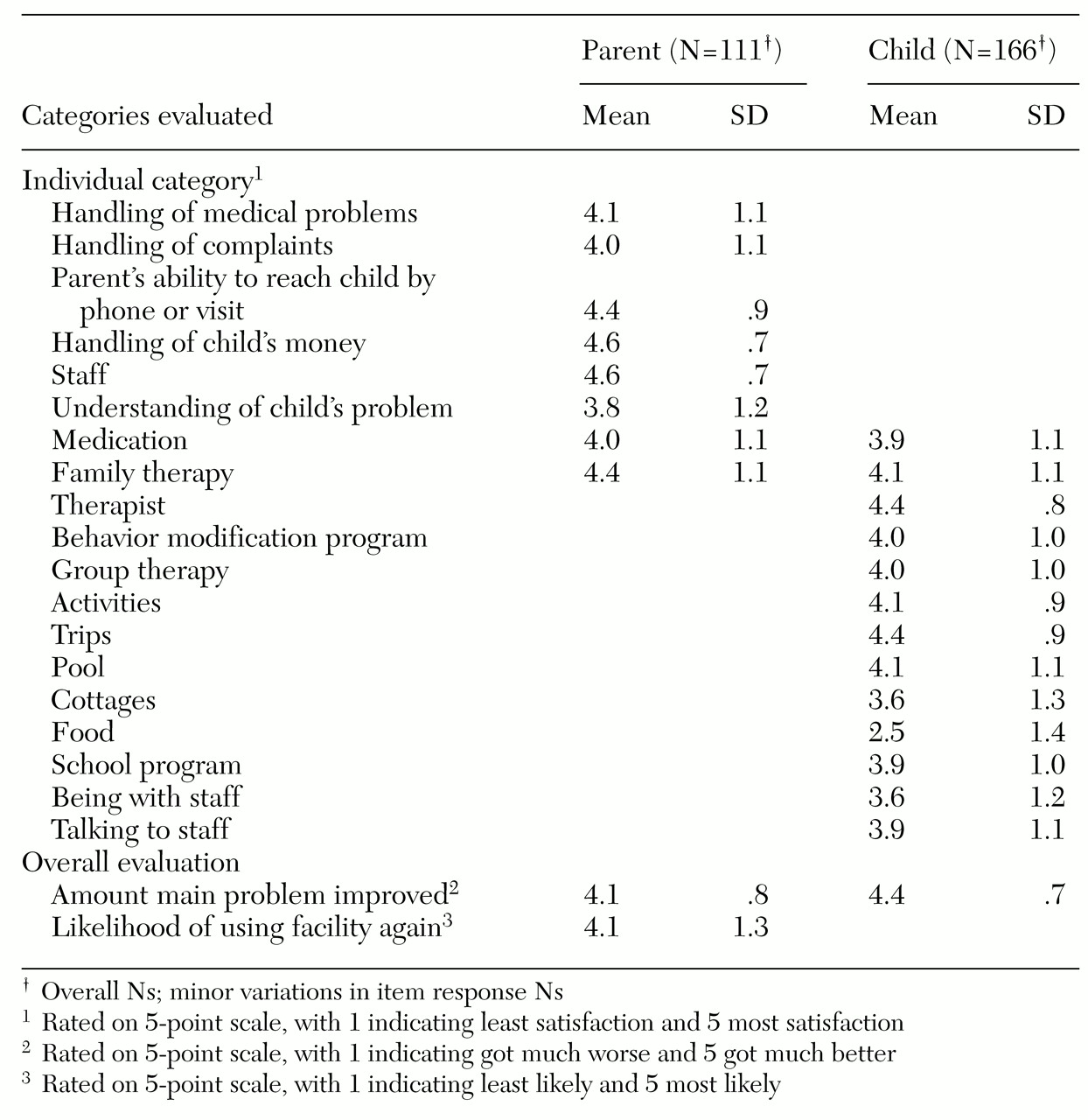

The overall ratings across the groups from the three sampling waves reflected high levels of satisfaction with services received, a high degree of perceived change in the problem that led to hospitalization, and a high likelihood of using the facility again.

Table 2 presents the participants' ratings.

Perception of abuse

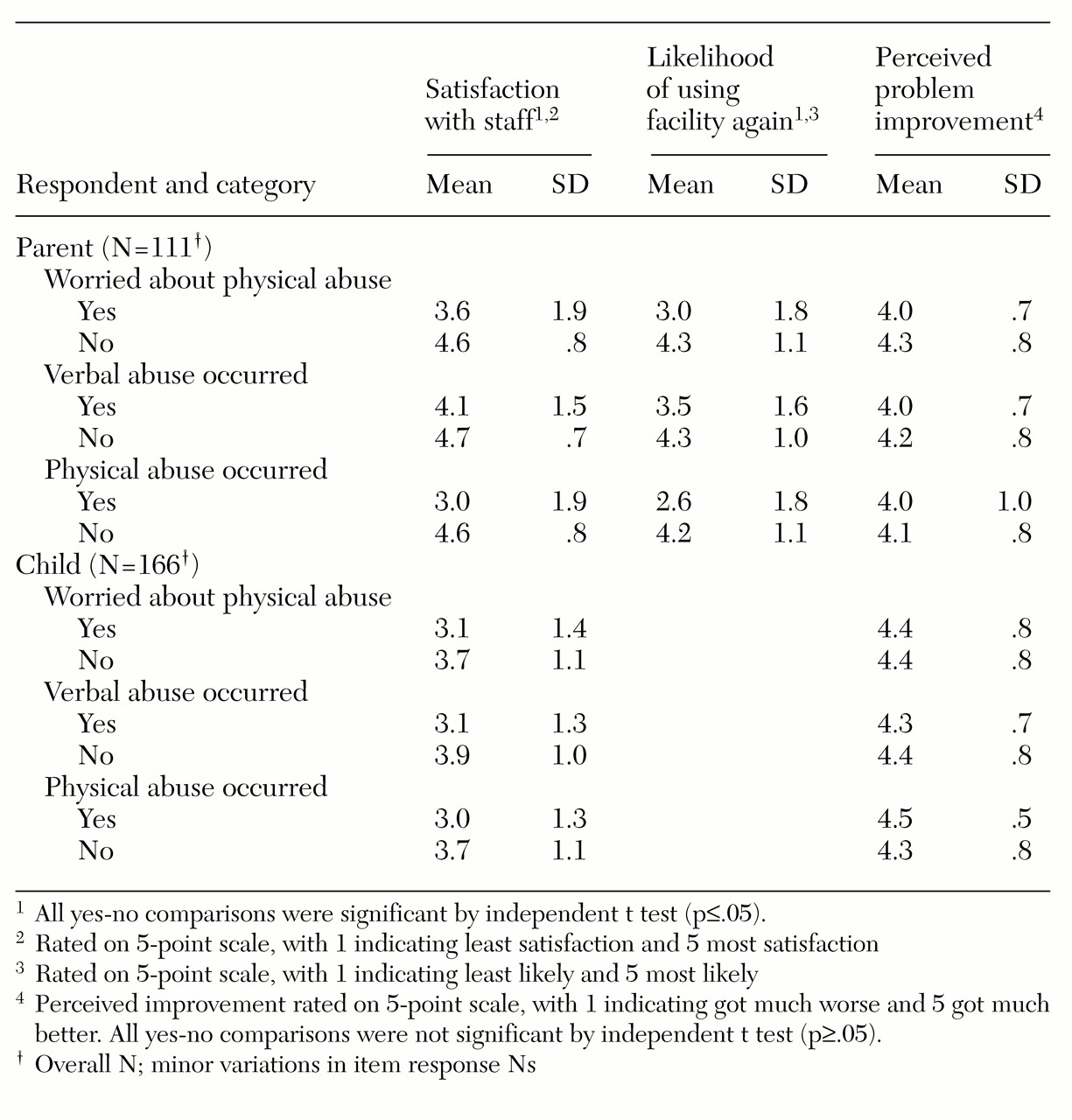

Disturbingly, 21 percent of parents and 28 percent of children reported that a staff member had verbally abused a child and 5 percent of parents and 10 percent of children reported physical abuse by a staff member. Less than 1 percent of parents and 1 percent of children reported sexual abuse by a staff member.

We categorized the child and parent samples into those who did and those who did not report either worrying about abuse or actual abuse. Reports of sexual abuse were excluded because the prevalence was too low for statistical comparisons. Comparisons were then made on ratings of satisfaction, perceived improvement of the problem, and the likelihood of using the facility again. As shown in

Table 3, children liked the staff less if they were worried about abuse or if they reported abuse. Among parents, satisfaction with staff and the likelihood of returning were significantly lower among those who reported that their child had experienced abuse. By contrast, parents' or children's perceptions about problem improvement were not associated with whether or not they reported abuse.

Problem improvement and likelihood of return

A principal components analysis of parents' satisfaction ratings yielded three factors. The first factor accounted for 35.4 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with the staff's understanding of the child's problem, the staff's handling of complaints, and the parents' involvement in therapy. This factor, labeled parent needs, had an internal consistency reliability (alpha) coefficient of .73. The second factor accounted for 14.6 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with medication use and attention to medical problems. This factor, labeled medical services, had an alpha of .69. The third factor accounted for 13.3 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with staff and procedures such as those governing visitation. This factor, labeled staff-facility, and had an alpha of .62.

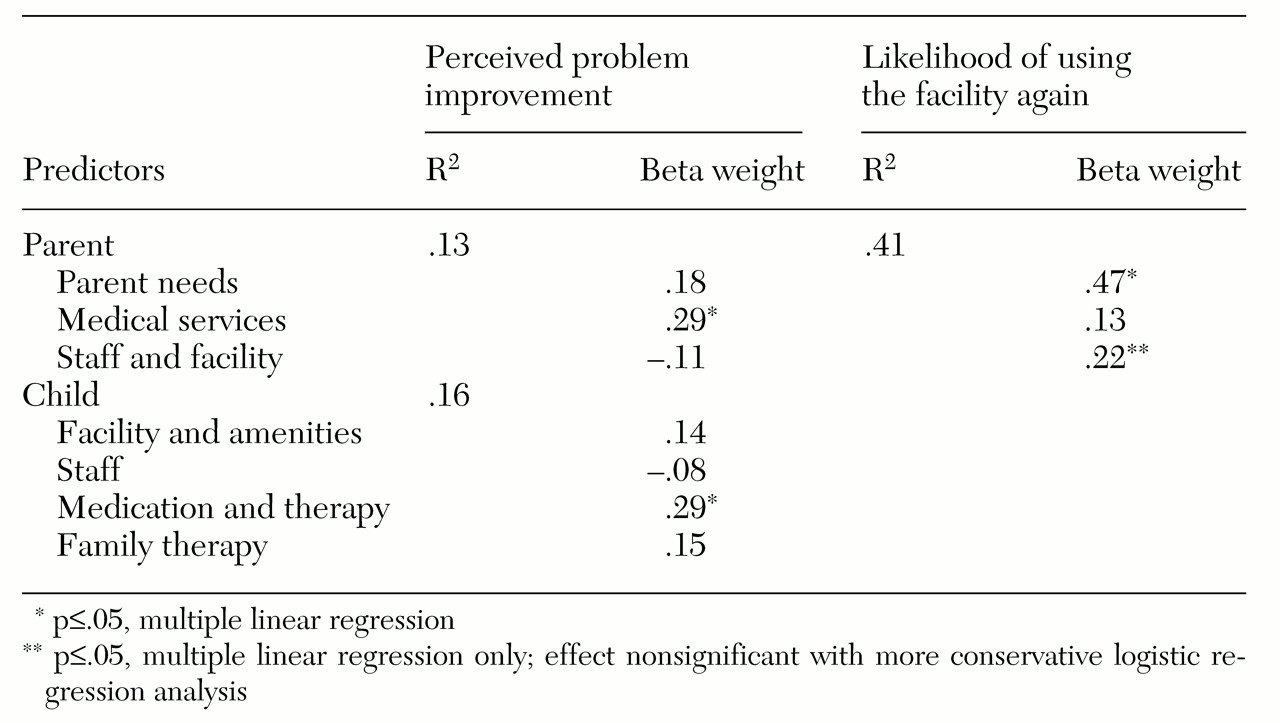

Factor scores were used to predict perceived problem improvement and likelihood of using the facility again as rated by parents. As shown in

Table 4, the three factors explained significant amounts of variance in both items (perceived problem improvement, R

2=.13, p<.001; likelihood of returning, R

2=.41, p<.001). Medical services was the only unique predictor of perceived problem improvement, while parent needs and staff-facility predicted the likelihood of using the facility again.

The scatterplots of predicted and residual values for prediction of perceived problem improvement showed no evidence of significant violations of normality, homoscedasticity, or linearity. The scatterplot for prediction of the likelihood of return showed evidence of nonnormality, manifested by negative skewness of residuals at higher predicted values. Transformations of the data did not correct this problem.

A simultaneous logistic regression was then performed. The likelihood of using the facility again was dichotomized by use of a median split (median=4.11), resulting in one group of 49 cases (29.5 percent) and one group of 117 cases (70.5 percent). The resulting logistic model was statistically reliable (χ2=45.7, df=3, plt;.001; classification accuracy=82.5 percent). However, only parent needs emerged as a significant predictor of return likelihood (odds ratio=2.3, 95 percent confidence interval=1.5 to 3.5). Both medical services and staff-facility yielded nonsignificant odds ratios.

The principal components analysis of the child satisfaction ratings yielded four factors. The first factor accounted for 31.3 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with the facility and its amenities—for example, activities, trips, and cottages. It was labeled facility-amenities, and it had an alpha of .75. The second factor accounted for 9.5 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with staff. It was labeled staff, and it had an alpha of .77. The third factor accounted for 8.8 percent of the variance and reflected satisfaction with medications and individual and group therapy. It was labeled medication-therapy and had a relatively low alpha of .54. Only one item—satisfaction with family therapy—loaded on the final factor, which accounted for 8 percent of the variance.

Regression was used to predict the children's perceived improvement of their problem from these four factors, and a statistically significant equation emerged (R

2=.16, p<.001). Only satisfaction with medication or therapy uniquely predicted perceived problem improvement, as shown in

Table 4. The scatterplot of predicted and residual values revealed linearity, relatively normally distributed residuals, and no evidence of heteroscedasticity.

Discussion and conclusions

Both parents and children reported high satisfaction with the services provided by the hospital, and they reported that the problem that had led to hospitalization had been greatly helped. However, it is characteristic of consumer satisfaction surveys that patients and other consumers rate themselves as highly satisfied, regardless of the quality of services provided (

2,

13). An often-used theoretical explanation for this phenomenon is drawn from cognitive dissonance theory (

14)—that is, to the extent that a consumer believes he or she has freely chosen a service, acknowledging that the service is poor will be discrepant (dissonant) with the consumer's self-perception as a wise chooser of services. A drive to avoid dissonance in this scenario, then, would tend to push the consumer's attitude toward service in a more favorable direction.

The high abuse rate reported by the parents and children in our sample indicates that despite the high rates of satisfaction reported, the patients and their parents were able to criticize the hospital. To elicit information about untoward events, specific inquiries seemed to be required.

We hypothesized that parents' and children's ratings of problem improvement would be strongly related to ratings of overall satisfaction, and that those who had obtained the help they had sought would be inclined to value the service highly. An important issue raised by our study is the interpretation of the parental report that the child's problem had improved: Is such a report a valid judgment of the child's clinical improvement, or is it just another global measure of consumer satisfaction and largely unrelated to any change in the child's clinical condition? Bickman and colleagues (

13) have provided the best study of this problem to date in the Fort Bragg experiment. In a confirmatory factor analysis of two mental health systems, they concluded that parent ratings of problem improvement were simply another measure of consumer satisfaction.

The data from our study provide an additional opportunity to examine the relationship between parents' ratings of children's improvement and parents' satisfaction with services. We factor analyzed the parent's satisfaction ratings and used the factors as independent variables in two multiple linear regression equations. In the linear regression equation in which the willingness to come back to the hospital was the dependent variable, the four factors of consumer satisfaction together explained 41 percent (R=.64) of the variance in willingness to return to the hospital. Willingness to come back is a critical measure of consumer satisfaction, because, from an economic perspective, all other indexes of consumer satisfaction are directed to achieving an affirmative response to this query.

The identified parental satisfaction factors explained only 13 percent (R= .36) of the variance of the dependent variable, problem improvement. We concluded from these analyses that parents' satisfaction is significantly but only weakly related to parent-rated problem improvement and much more strongly related to another measure of consumer satisfaction, willingness to return to the hospital.

That parents' assessment of the children's improvement reflects something largely distinct from consumer satisfaction is most clearly demonstrated in the analyses comparing measures of consumer satisfaction and problem improvement ratings among parents who did and did not complain of abusive staff behavior. Both groups reported substantial problem improvement, but the parents who complained of abusive staff behavior were much less satisfied with the hospital than those who did not complain.

Parents are not the only ones who can discriminate between problem improvement and satisfaction with the hospital; child patients make similar discriminations. Children who complained of staff abuse reported a level of problem improvement that was statistically similar to that reported by children who did not complain of abuse, yet they reported significantly less satisfaction with the staff than did their counterparts.

The amount of variance in perceived problem improvement explained by consumer satisfaction factors among children (16 percent) was almost identical to the amount of variance in perceived problem improvement explained by the parent factors of consumer satisfaction (13 percent). This finding suggests that for both children and parents the perception of problem improvement was largely independent of overall satisfaction.

Our study suggests that consumer satisfaction can be measured with satisfactory levels of response when consumers are individually approached and when a trained interviewer is present. Clinically, we were keenly interested in using a consumer satisfaction survey to identify intrainstitutional issues, and the survey did prove useful in identifying these areas for further administrative and clinical intervention. There may be clinical utility in performing surveys at multiple time points, as problems identified can be addressed and solutions later evaluated. Consumer satisfaction surveys that assess perceived problem improvement should include independent measures of clinical improvement along with parent- and child-rated global measures of improvement.