Researchers have documented the frequent occurrence of depression among patients who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (

1). Comorbid depression may increase suffering and suicide risk (

2) and has been associated with higher rates of relapse and rehospitalization (

3,

4), hopelessness (

5), and poor psychosocial skills (

6). Distinguishing depressive syndromes among patients with schizophrenia is challenging (

7,

8), and past research has focused on diagnostic differentiation between affective disorders and co-occurring schizophrenia and depression (4,9-11). Nevertheless, the negative effects of depression on people with schizophrenia make recognition of comorbid disorders particularly important for proper treatment and improved outcome.

African Americans are less likely than Caucasians to receive a diagnosis of affective disorder and more likely to receive a diagnosis of psychotic disorder (

12,

13,

14,

15,

16). Theories about the mechanisms of this effect include diversity of symptom presentation (

17,

18), misinterpretations of symptoms by clinicians—often Caucasian—with low levels of cross-cultural competence (

19,

20,

21,

22,

23), sociocultural differences in treatment-seeking behavior among patients (

22,

24,

25), and lack of cultural sensitivity in diagnostic instruments (

19,

20,

26). The overdiagnosis of psychotic disorders and underdiagnosis of affective disorders among African Americans persist despite a lack of data suggesting actual differences between racial groups in illness prevalence, particularly when analyses are controlled for other demographic variables, such as marital and socioeconomic status (

27,

28).

Methods

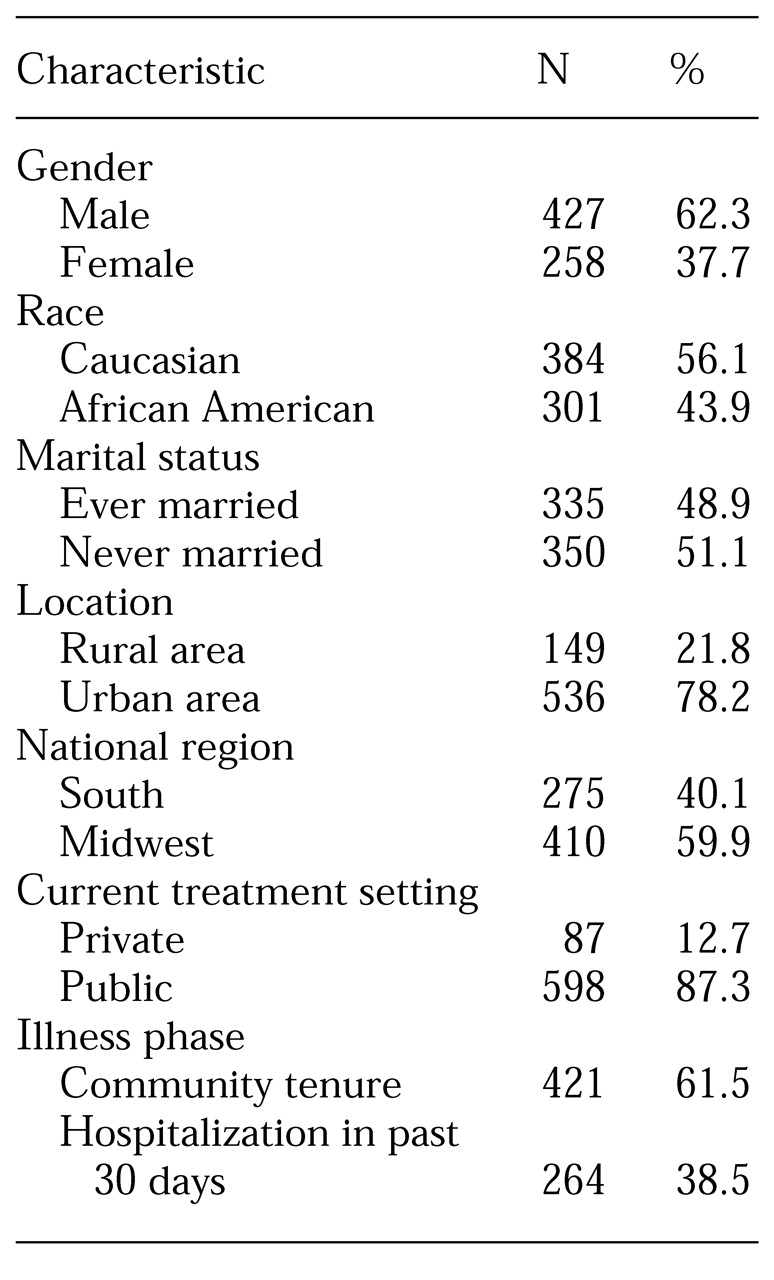

In the PORT patient survey, face-to-face interviews were conducted from 1994 to 1996 in two states, one in the South and the other in the Midwest, with a random sample of 719 persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. All participants provided written informed consent and received a $10 honorarium. They completed a 90-minute structured interview and permitted a review of their current medical record. The details of this procedure have been reported elsewhere (

34).

Sample

The study participants were a random sample—although not necessarily an epidemiologically representative one —of persons currently receiving treatment for schizophrenia. Treatment settings included acute inpatient and outpatient programs, both in the public and private sectors, including the Department of Veterans Affairs. The PORT sampling strategy had four levels: states, communities, providers, and patients. After states were selected and agreement to conduct the study was obtained from mental health commissioners, five communities in each state, including at least one rural community, were randomly chosen. Treatment providers in each community were then sampled. Finally, within each provider setting, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were selected at random from treatment rosters. All participants met the study criteria of having a current clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, being an English speaker, being at least 18 years old, being legally competent, and living in the local community.

A total of 1,680 people were screened as initially eligible for the survey (663 inpatients, 1,017 outpatients), and 62 percent of them (458 inpatients, 584 outpatients) agreed to have their names released to the study. Of these, 948 met more detailed eligibility criteria (398 inpatients, 550 outpatients), and 719 (76 percent) of them completed the survey interview. Inpatients were interviewed approximately 90 days after discharge. Staff at each site were able to provide the age, gender, and race of persons who refused to have their names released while keeping their identity completely confidential. No significant gender, race, or age differences were found between persons who gave permission to release their name and those who did not. Among those who did consent to have their name released, no significant gender, race, or age differences were found between those who consented to participate and those who ultimately declined.

Instruments and measures

This study analyzed data from the direct client survey of participants in the PORT study. Information on participants' gender, race, age, marital status, and education; self-reports of past and current diagnoses; and self-reports of current treatment for a variety of comorbid mental disorders and psychiatric symptoms were used to derive the variables for this study's analyses.

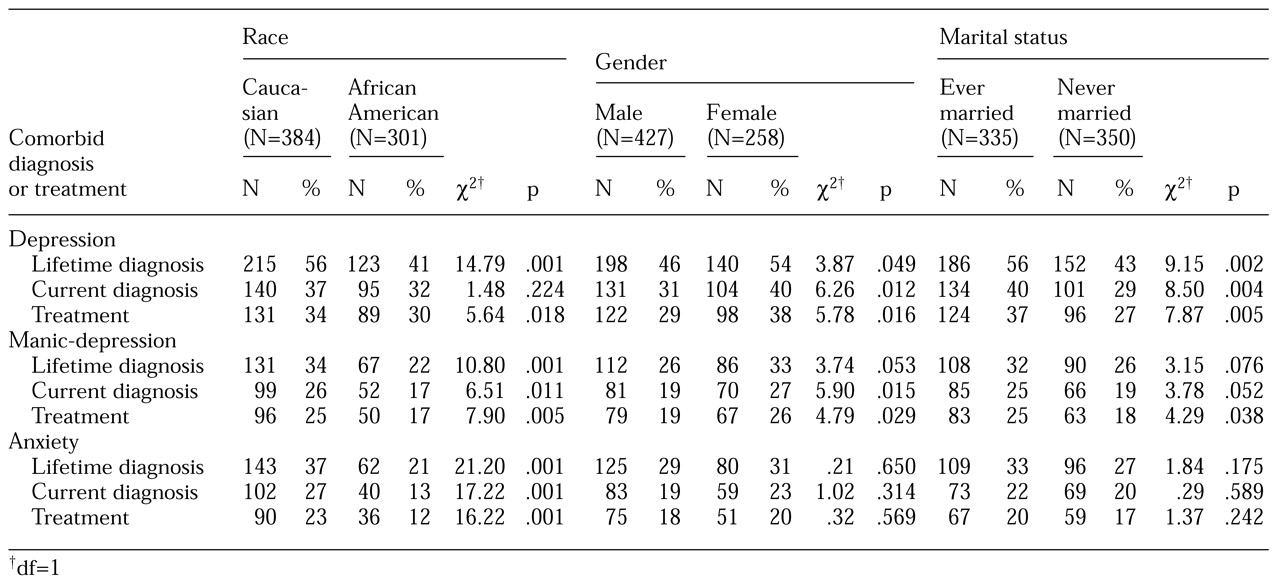

Comorbid affective and anxiety disorders. To determine lifetime diagnoses of comorbid affective and anxiety disorders, participants were asked whether they had ever been told by a physician that they had depression, including major depression or dysthymia; manic-depression or bipolar disorder; or an anxiety disorder, including panic, phobias, and obsessive compulsive disorder. Participants who responded affirmatively were then asked whether they currently had such a diagnosis. Those who reported current disorders were asked whether they were currently receiving treatment for them.

Psychiatric symptoms. Two measures were obtained by computation of the mean scores of the items that constitute the depression and psychoticism subscales of the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90), a self-report symptom measure (

35). For each item, respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they were distressed by that symptom during the previous week (from 1, not at all, to 5, extremely). In addition, an overall score was obtained by computing the mean of scores from all items in the two scales. Higher scores reflect more severe symptoms.

Data analysis

Bivariate and multivariate analyses were used to determine the association of race with other demographic characteristics and with a diagnosis of and treatment for comorbid affective and anxiety disorders. Age and educational level were evaluated as continuous variables, and the other demographic variables were evaluated as two-level factors. Marital status was defined as ever married (married, widowed, divorced, separated, communal living) or never married. Race was defined as Caucasian or African-American (others were excluded). Bivariate associations between depression and the categorical variables were assessed with chi square tests (two-tailed), and continuous variables were assessed with t tests (two-tailed).

The possibility of collinearity was examined by assessment of the degree of association between pairs of covariates. Women and older persons were more likely to have ever been married, and women were also older on average. African Americans had less education on average than Caucasians (mean±SD years of education, 11.50± 2.33 and 12.12±2.48, respectively; t=3.31, df=681, p<.001). Correlations between race and substance abuse were low and did not significantly affect the associations between race and diagnosis described later. None of these demographic associations caused problems with collinearity in the multivariate models.

Caucasians and African Americans did not differ significantly on total symptom ratings or ratings of depressive symptoms, according to the SCL-90 self-report. However, African Americans reported having more psychotic symptoms than Caucasians reported (mean±SD number of symptoms, 2.12±0.97 and 1.93±0.80, respectively; t=2.81, df=683, p<.01).

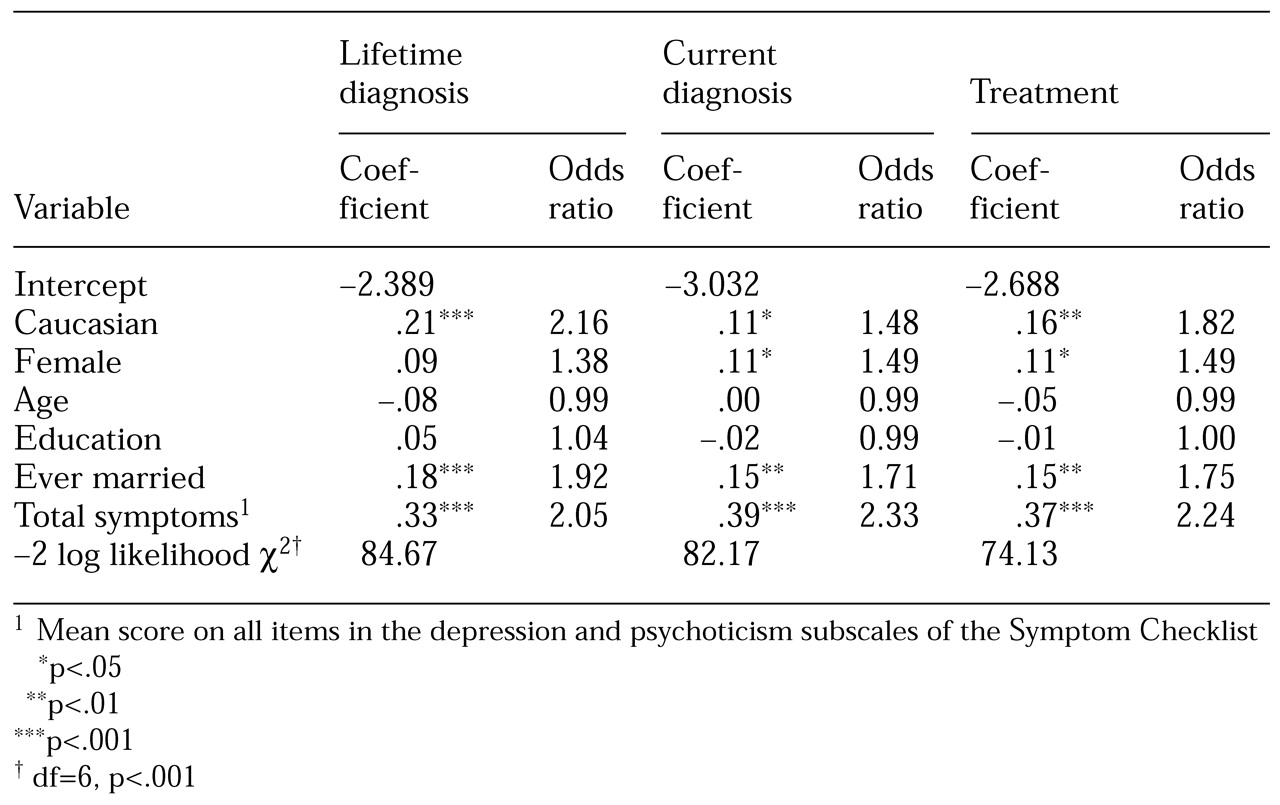

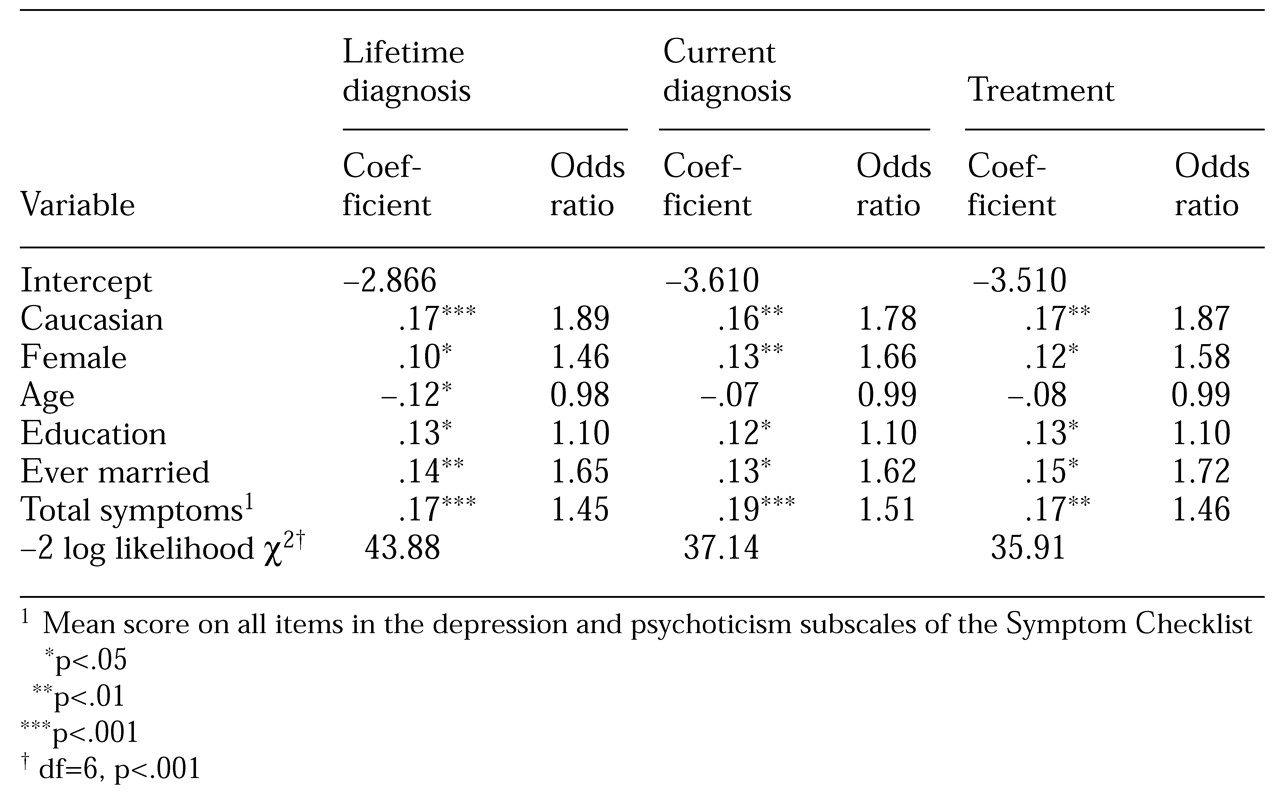

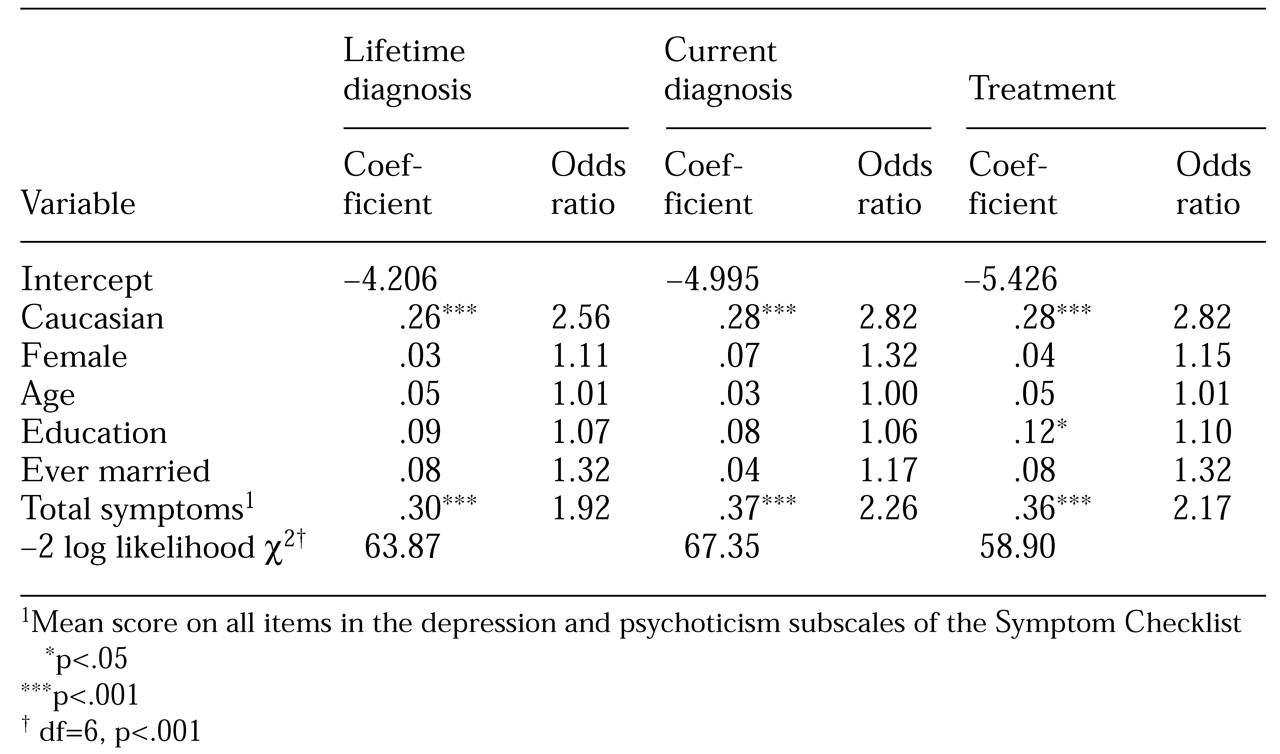

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate race as a predictor of depression. All of the demographic factors and symptom self-ratings were used as independent variables. A parallel set of analyses was conducted to evaluate race as a predictor of manic-depression and anxiety disorders. Although ratings for total symptoms, for psychotic symptoms, and for depressive symptoms were each considered as independent variables, our primary model used only total symptom ratings. We wanted to control for both psychotic and depressive symptoms in the prediction of diagnoses of affective disorders, because both symptom clusters could contribute to comorbid diagnoses. We used the -2 log likelihood statistic to assess the goodness of fit of our models (

36).

Discussion and conclusions

This study duplicates and extends our previous work on the apparent underdiagnosis of three affective disorders among African Americans with schizophrenia (

30). We found that Caucasian patients were more likely than African Americans to report lifetime and current diagnoses of and current treatment for depression, despite similar levels of self-reported depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with other PORT findings that African Americans who were depressed according to a variety of criteria were less likely than Caucasians to receive antidepressants (

33).

African-American participants were also less likely to report having received lifetime or current diagnoses of bipolar and anxiety disorders and were less likely to be receiving treatment for either type of disorder. Underdiagnosis of anxiety disorders among African Americans in the U.S. general population has previously been suggested but has not been consistently supported (

37,

38). Friedman and associates (

39) identified distinct characteristics of African Americans and Caucasians presenting for treatment at an anxiety disorders clinic but found that the two groups did not differ significantly in psychiatric symptoms, a result replicated in a group of medical patients (

40). In contrast, Wohi and colleagues (

41) compared matched samples of Caucasians and African Americans who had depression and found that Caucasians had more anxiety symptoms as part of their depression. Clearly, more research on the influence of race in the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders is needed. To our knowledge, our study is the first to identify the possibility of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of anxiety disorders among African Americans with schizophrenia.

African Americans were also less likely than Caucasians to report having received a diagnosis of or being treated for manic-depression. This finding is consistent with previous research findings of elevated rates of misdiagnosis of schizophrenia instead of bipolar disorder among African-American patients (

14,

42). In addition, Liss and associates (

43) found that African-American patients are more likely than Caucasians to present with hallucinations and delusions during episodes of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Given that the African Americans in our sample also reported more psychotic symptoms, differences in symptom presentation may lead to clinicians' more frequently confusing bipolar disorder with schizophrenia among African Americans. In addition, this confusion may be related to the use of Caucasian patients' presentation of symptoms as the basis for most research and diagnostic tools.

Social class may be an important intervening factor. Although this variable was not measured in our study, one can speculate about its effect by viewing level of education as a rough indicator of socioeconomic status. The positive correlations in our study between educational attainment and the diagnosis and treatment of manic-depression and anxiety disorders and the negative correlation between African-American race and educational attainment suggest a possible effect. Thus class differences between African-American and Caucasian participants may account for at least some of the disparities in diagnosis and treatment, although education was controlled for in the multivariate analyses.

The relationship between race and treatment across all three comorbid diagnostic groups is also troubling. Significantly fewer African Americans with schizophrenia reported currently receiving treatment for affective disorders. Patients who present with more than one cluster of clinical symptoms may be more likely to be treated only for what is perceived to be the most serious symptoms, such as psychosis. We found that African Americans reported more psychotic symptoms on the SCL-90, and such a treatment tendency could be operating for this group. However, standard care includes assertive treatment of both affective and psychotic symptoms, whether they are comorbid or are constituents of the same disorder, so this effect may reveal a deficit in care.

In addition, it is unclear why African Americans reported more psychotic symptoms than Caucasians. The African Americans in our sample may have been sicker than the Caucasians, possibly as a result of delays in seeking and receiving treatment, poorer treatment response, or less adequate antipsychotic treatment.

Another possibility is a bias in the instruments used to measure psychotic symptoms. The validity of the SCL-90 as a specific measure of psychotic symptoms has been challenged (

44,

45,

46,

47). In addition, various authors have cautioned against interpreting African Americans' appropriate cultural mistrust of the medical establishment and researchers as the paranoid ideation of psychosis (

48). Moreover, race-correlated self-report biases—perhaps related to cultural differences in the acceptability of mental illness models of distress, of the diagnostic label of depression, or of self-disclosure about such experiences—may have contributed to the differences we found.

The effects of marital status and gender were also noteworthy. Marriage was associated with a greater likelihood of having received diagnoses of depression, manic-depression, and anxiety disorders in our sample. This finding replicates the results of our previous study (

30) and is consistent with the idea that depression co-occurring with schizophrenia is associated with characteristics that predict a better overall prognosis. Among persons with schizophrenia, marriage is relatively uncommon for men and more prevalent for women, and it is associated with enhanced social functioning (

49,

50,

51). Persons who have been married and who have better social functioning are more cognizant of the deterioration in their lives as a result of their symptoms. Consequently, they may be more likely to become depressed. Persons who have never been married and who thus have poorer social functioning may have a different form of schizophrenia—the deficit syndrome (

52,

53), which is associated with less vulnerability to depression.

Women were more likely than men to have a current diagnosis of depression and to be treated for the disorder, and they were more likely to have lifetime and current diagnoses and current treatment for manic-depression. These findings are generally consistent with patterns of depression in general populations. There is robust evidence that, overall, women experience depressive symptoms and clinical depression and receive treatment for depression more often than men (

54,

55). This difference is thought to be at least partly attributable to gender differences in chronic life stress (

55).

Also, persons who are in chronically stressful marriages or other long-term relationships have a greater tendency toward depression, whereas positive marriages and relationships can enhance mental health, especially for men (

56,

57). We found that people who had ever been married were more likely to have received a diagnosis of depression, which may suggest that their constellation of stressors included difficult marriages, possibly because of their schizophrenia symptoms. It is noteworthy that 62 percent of the ever-married participants (208 of 335 participants) were divorced, separated, or widowed at the time of the study.

Our study had some specific limitations. One of these is the self-report nature of the data we used. Self-reports may have been subject to recall bias as patients attempted to respond to questions about past diagnoses and even current diagnoses and treatment, although nothing in the data suggests that this bias could account for the race and gender differences we found. In addition, our confidence in the self-report data is reinforced because participants' responses were consistent with well-documented patterns of diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders among African-American and Caucasian patients.

Furthermore, self-reports are an important source of information in clinical care, and patients are the main source of information about their symptoms. Nonetheless, self-report of symptoms is limited by a variety of possible biases, including social desirability and cultural differences in disclosure. Given our reliance on self-report data, the race-linked differences causing the effects we noted may not have been in diagnosis or treatment but rather in strategies for informing patients about their diagnoses and what they are being treated for. Another possibility is that the patients may not have fully understood the questions that were being asked and thus may not have been providing the information that was being sought.

Despite these limitations, our data suggest the possibility of racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with schizophrenia and comorbid affective and anxiety disorders. Further studies are needed to clarify this issue and to identify ways to correct the contributing factors.