Measures

Counseling rapport. The measure of counseling rapport that we used is based on ratings from counselors of their patients; patients' ratings were more highly skewed, mostly toward the upper end of the scale, and were less discriminating than counselor ratings (

19,

22). The data provided an opportunity to examine the robustness of this construct, because there were differences in the cohorts as well as some variation in the scale itself between the two cohorts.

The instrument that was used to record these process ratings underwent several stages of experimental testing and refinement from cohort 1 to cohort 2. The wording of some of the items was modified, and two different response formats were used. In cohort 1, the ratings were based on a 5-point Likert scale for frequency of occurrence—never, rarely, sometimes, often, almost, or always—at months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 of the index treatment. Six items were used to define counseling rapport: "easy to talk to," "warm and caring," "honest and sincere," "understanding," "not suspicious," and "not in denial about problems." The alpha reliabilities of this scale were .80, .79, .81, .78, .82, and .82 for months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12, respectively.

In cohort 2, the ratings were based on a 7-point Likert scale that indicated the level of agreement—ranging from "disagree strongly" to "agree strongly"—at months 3, 6, 9, and 12 of the index treatment. The scale consisted of five items— "easy to talk to," "warm and caring," "honest and sincere," "not hostile nor aggressive," and "not in denial about problems"—and had coefficient alpha reliabilities of .79, .81, .83, and .81 for months 3, 6, 9, and 12, respectively.

For the purposes of this study, each patient's scores were averaged over the full length of stay in the index treatment episode and dichotomized. For cohort 1, the average score could range from 0 to 4 and was dichotomized at 2.5 because of distributional skew, with scores of 2.5 or above indicating a frequency rating of "more than sometimes." About half of the patients (183, or 52 percent) had scores of 2.5 or above. Patients whose average score was 2.5 or above were coded as 1, and those whose score was below 2.5 were coded as 0.

For cohort 2, the average score could range from 1 to 7 and was dichotomized at 5, with scores of 5 or higher representing "agreement" and thus higher levels of perceived rapport between the counselor and the patient. In the distribution of this variable, 93 of the patients had average scores of 5 or above. Patients whose scores were 5 or above were coded as 1, and those with scores below 5 were coded as 0. Because the counselors did not rate the patients in cohort 2 until month 3, no ratings were available for 39 patients who had dropped out of treatment before ratings had been made. For analytic purposes, these patients were included with those who had scores below 5. With these additions to the low-rapport category, patients with scores above 5 constituted about 42 percent of the sample (93 patients). This procedure was deemed acceptable because of the similarity of the results between the samples with and without these patients.

Posttreatment outcomes. At the follow-up interview, a urine specimen was obtained and tested for opiate—excluding methadone—and cocaine metabolites. The urine specimens were analyzed with use of the enzyme multiplication immunoassay technique. Other post-index treatment outcomes included self-reported use of heroin and of cocaine, illegal activity, and arrests during the six months before the interview. Illegal activity was defined as any self-reported illegal activity during the six months before the interview or a stay in jail during that time. Individuals who were in prison at the time of follow-up were not interviewed and were excluded from the analysis, which may have reduced the level of illegal activity reported.

Covariates. In the logistic regression analyses, the importance of counseling rapport as a predictor of outcomes was tested relative to treatment retention, satisfaction with treatment, and post-index treatment status. Satisfaction with treatment was based on the results of a factor analysis of patients' ratings of treatment services at months 3, 6, 9, and 12 of treatment and was defined by five items—overall satisfaction, location, staff efficiency, meeting time of the session, and whether the session was organized and well run. The alpha reliabilities for satisfaction with treatment were .67, .77, .75, and .73 for months 3, 6, 9, and 12, respectively. Treatment retention was defined as a duration of treatment of at least a year. In cohort 1, a total of 134 patients (38 percent) met the criterion for treatment retention, compared with 167 patients (47 percent) in cohort 2. Patients who met this criterion were coded 1, and those who did not were coded 0.

Analyses

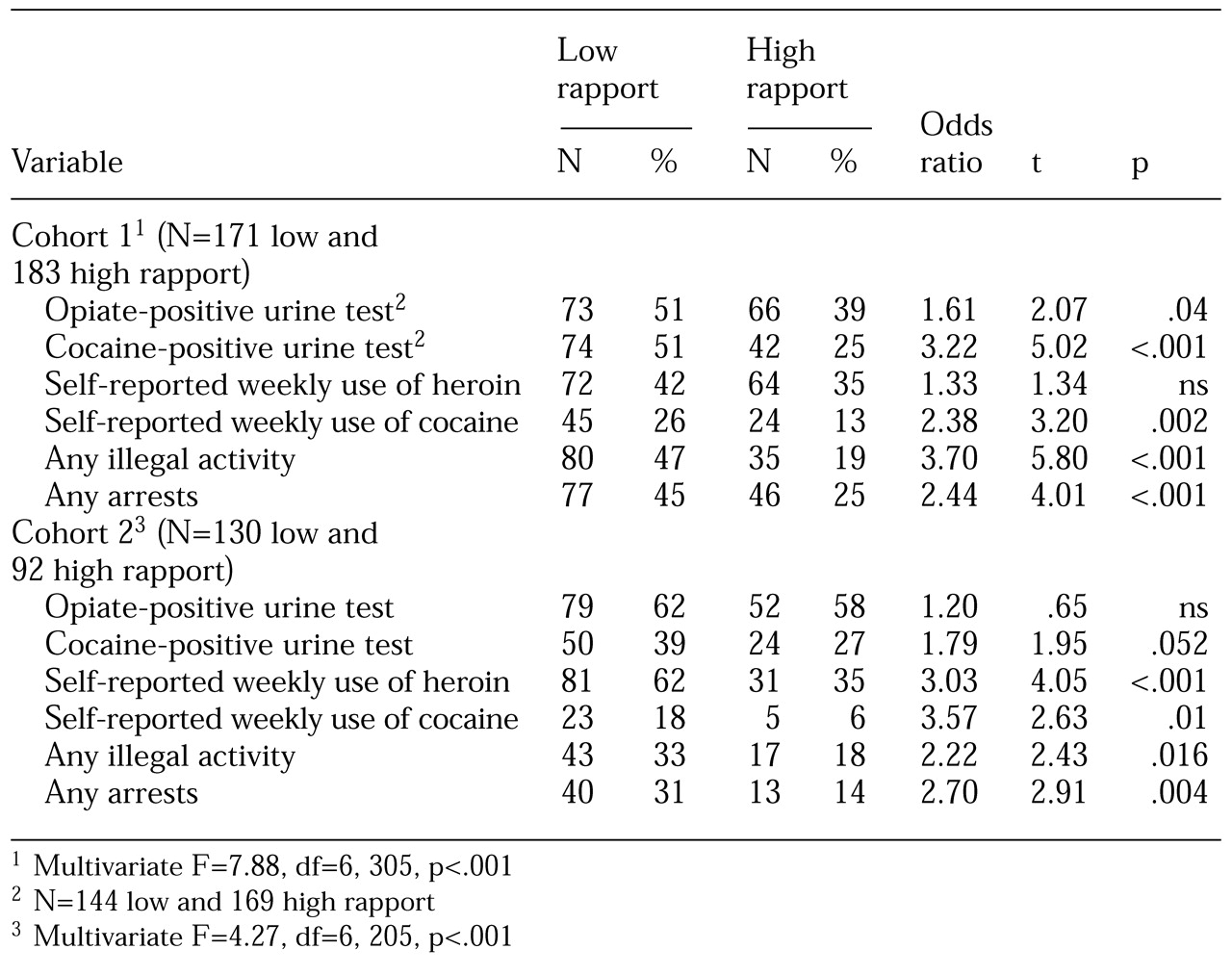

The analyses addressed six post-index treatment outcomes: urine tests that were positive for opiate metabolites or for cocaine metabolites, self-reported use of heroin and cocaine, any illegal activity, and any arrest. Initially, a multivariate analysis of variance was performed to test overall differences between the effects of different levels of counseling rapport on these six outcomes. To identify the components contributing to the significant results of the multivariate test, we then conducted separate analyses of variance for each of the six outcomes.

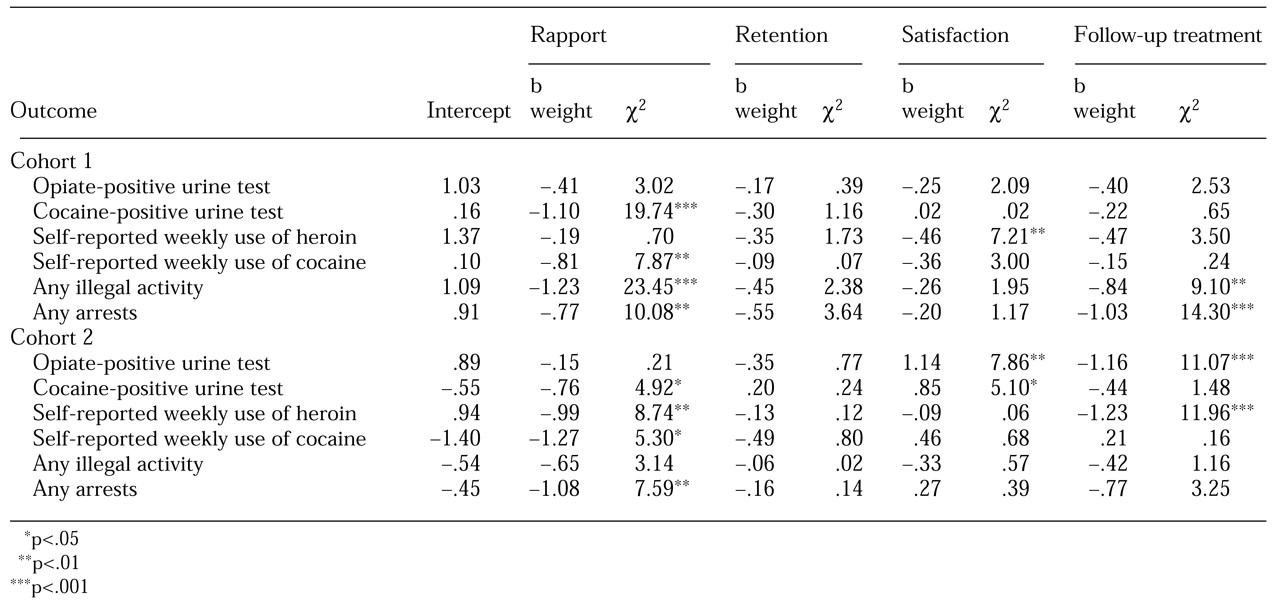

This procedure was followed by logistic regression analyses in which treatment retention, satisfaction with treatment, and post-index treatment status were used as covariates to further examine the significance of counseling rapport relative to the covariates as a predictor of post-index treatment outcomes.

Because treatment retention traditionally has been a consistent predictor of post-index treatment outcomes, it represents an important alternative hypothesis for explaining relationships between counseling rapport and these outcomes. Similarly, satisfaction with treatment is an alternative that might predict outcomes. Also, because patients often transfer to or enter another treatment episode after the index treatment that is being studied, the effects of counseling rapport on the post-index treatment outcomes should be adjusted for treatment status during the follow-up interview. In essence, the relative importance of counseling rapport is addressed by adjusting it for treatment retention in the index treatment, satisfaction with treatment, and treatment status at the follow-up interview. Next, counseling strategies are examined as variables that predict counseling rapport.

Finally, these analyses were replicated in the cohort 2. The availability of similar data across these somewhat diverse cohorts provided an opportunity to test the robustness of the findings. The importance of counseling rapport to outcomes was viewed as a central treatment process variable that would be expected to affect outcomes similarly in the two cohorts.