Subjects and randomization

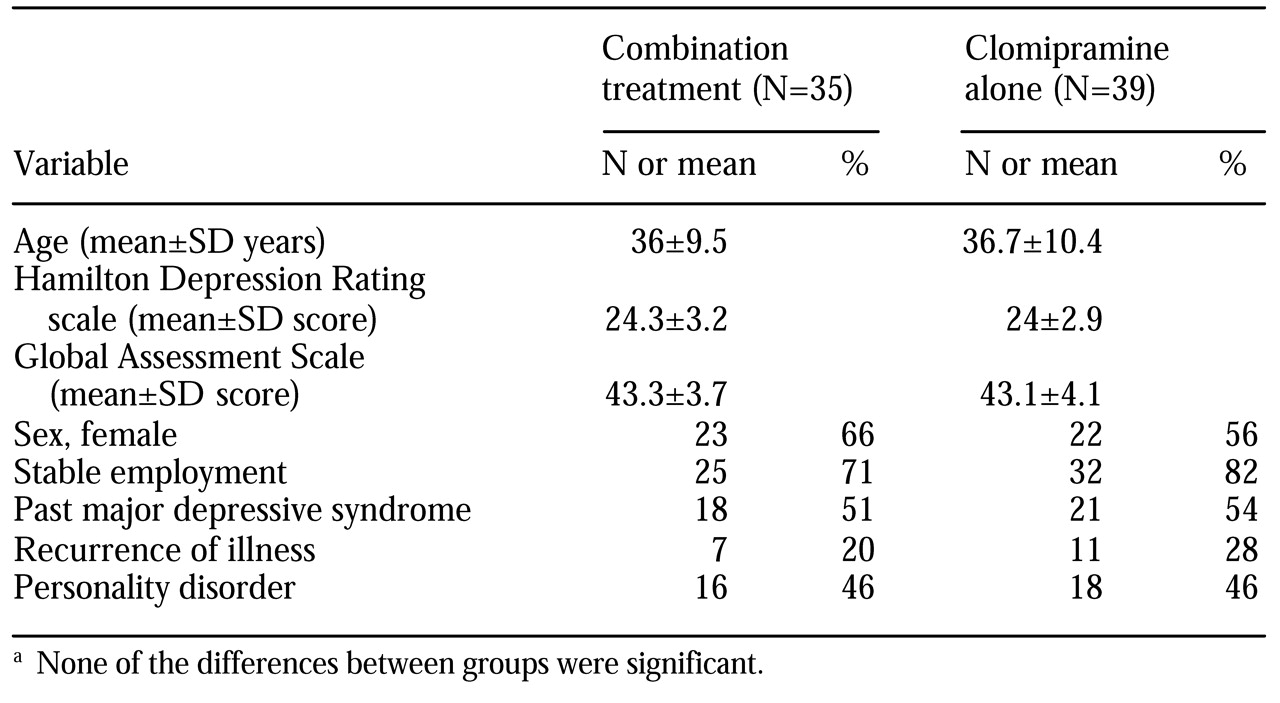

Between 1994 and 1996, a psychiatrist and a research nurse screened consecutive patients who were referred for acute outpatient treatment at a community mental health center. A total of 390 patients between the ages of 20 and 65 years with a new episode of care and symptoms of depression were selected by four independent psychologists. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of a major depressive episode on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), whatever the severity of any concurrent suicidal ideation, personality psychopathology, or past resistance to treatment, and a score of at least 20 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). (Possible scores on the HDRS range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more severe depression.) Exclusion criteria were bipolar disorder, psychotic symptoms, severe substance dependence, organic disorder, mental retardation, history of severe intolerance to clomipramine, and poor command of the French language.

The ethics committee of the department of psychiatry at the University of Geneva approved the study. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient before assignment to treatment.

A total of 110 patients were eligible for the study. Ten of these were diverted to another study, and five dropped out before randomization. The remaining 95 patients were randomly assigned to one of the two outpatient treatment groups on an intent-to-treat basis—47 to the combined treatment (experimental) group and 48 to the clomipramine (control) group. The random assignment process included stratification by presence of personality disorders, past major depressive syndrome, and gender.

Twenty-one patients (12 in the experimental group and nine in the control group, or 22 percent) were excluded from the analyses—four who did not return for treatment (three in the experimental group and one in the control group), three who dropped out against medical advice (two in the experimental group and one in the control group), and 14 who were discharged because they had exclusion characteristics that were not detected at entry, including severe alcohol or drug dependence (five in each group) and adverse effects (two in each group). These patients were not significantly different from the other patients in terms of the main outcome variables at intake. The 74 patients who completed the study were not significantly different from the 21 who were withdrawn or from the group of 95 as a whole.

Treatment

We compared two ten-week acute treatment programs for major depression: clomipramine combined with psychodynamic psychotherapy and clomipramine alone. Both treatments involved the same clomipramine protocol and intensive nursing in a specialized milieu. In addition, the amount of structured psychodynamic psychotherapy provided during combined treatment was comparable to the amount of supportive care provided during treatment with clomipramine alone. Supportive care involved individual sessions aimed at providing empathic listening, guidance, support, and facilitation of an alliance by one carefully designated caregiver.

To ensure reliable standards of treatment, distinct nursing teams were trained for six months in the use of specific manuals. The attendant psychiatrist and the chief nurse agreed on the following guidelines for referring a study patient to inpatient care: a change to a manic episode, suicidal threats or severe lack of control and disruption to the alliance or to interpersonal bonds, severe inhibition preventing attendance at the center, a serious threat to caregivers and significant others, and a confused state. A careful review indicated that all guidelines were followed.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy. Preliminary reports on patients treated with psychodynamic psychotherapy have focused on the relationships between the alliance process and outcome (

14), indicating that both nonspecific and specific ingredients of psychotherapy contribute to successful crisis intervention among patients with depression (

15). It has been observed that a "treatment barrier" associated with personality psychopathology produces traumatic experiences and acute interpersonal conflicts in patient-caregiver relationships (

16). The inactivation of such a barrier predicts alliance, treatment response, and outcome (

14).

Thus for this study we made several assumptions. First, we assumed that alliance is an intersubjective process that depends on personality traits and management of resistance, impasse, and rupture (

17). Second, we assumed that these obstacles to the alliance are activated by acute narcissistic discomfort that stems from various combinations of current traumatic experiences and enduring conflicts between the idealized expectations of the infant and the realistic needs of the adult. Third, we assumed that the treatment barrier prevents an adequate response to antidepressant treatment by standing in the way of a positive self-image and reinvestment in rewarding interpersonal relationships (

14). Finally, we assumed that, when framed as a mourning process, psychodynamic psychotherapy and its supervision may break the vicious cycle between narcissistic discomfort and the reinforcement of pathological personality traits, thus inactivating the treatment barrier and its negative effect on the remission process.

Designated effective ingredients of psychodynamic therapy are a structure for the therapeutic relationship, empathy and emotional expression, insight, awareness, and facilitation and reinforcement of new interpersonal bonds. The corresponding appropriate interventions for obtaining these ingredients are emphasis of the value of therapeutic relationships and their evolution; facilitation of affect catharsis through empathic listening to the unique personal experience of the patient and active designation (expression in verbal terms) of the overwhelming feelings underlying his or her distress; recollection of present and past life crises that offer insight into enduring patterns of maladaptive interpersonal relationships and psychological conflicts facilitating bond disruption; focus on compulsive idealization of the corresponding attachment styles, beloved objects, and grandiose self-images and on the active ignorance of the unpleasantness of such processes; and breaking away from excessive concern about separation, deception, and loss to reinforce better self-caring, help seeking, and new investments. The corresponding treatment stages are nonspecific alliance process and psychoeducation, working alliance, insight, focusing, awareness, mourning, and reality reinvestment.

Four nurses were selected on the basis of their proven clinical experience (more than five years) with patients with depression, their crisis intervention practice under psychodynamic supervision (more than two years), and their demonstrated psychotherapeutic skills with patients with depression.

The nurses who worked with the patients who received combined treatment had weekly supervisory sessions with a psychoanalyst. These sessions covered setting limits and maintaining an alliance, developing empathy, developing insight and awareness, clarifying patients' internal conflicts, and facilitating the separation process at the termination of treatment. According to psychoanalytic works that stress that unconscious conflicts are barely understandable in a psychiatric situation, the primary aim was to work out the "treatment barrier-like" reactions that undermined active cooperation and rational management of psychiatric treatment (

18). Nevertheless, the corresponding transference-countertransference relationships were investigated when they posed a major threat to continuation of treatment.

Clomipramine protocol. Clomipramine was administered at a dosage of 25 mg on the first day, gradually increasing to 125 mg on the fifth day. Electrocardiograms were performed before the start of the protocol and were repeated during weeks 1 and 2. Drug monitoring was conducted during weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 and at discharge. Clinicians were allowed to adjust the dosage of clomipramine on the basis of the patient's clinical status and achievement of an optimal plasma concentration of clomipramine plus desmethylclomipramine (between 200 and 300 ng/L). Previous studies have demonstrated a strong treatment response with this dosing strategy (

19). Alternative treatment consisting of 20 to 40 mg of citalopram a day was permitted for patients who refused the clomipramine treatment or experienced severe side effects.

Instruments and assessment

At intake and at ten weeks, three psychologists assessed the severity of depression with the SCID, the HDRS, and a Health-Sickness Rating Scale (HSRS) (

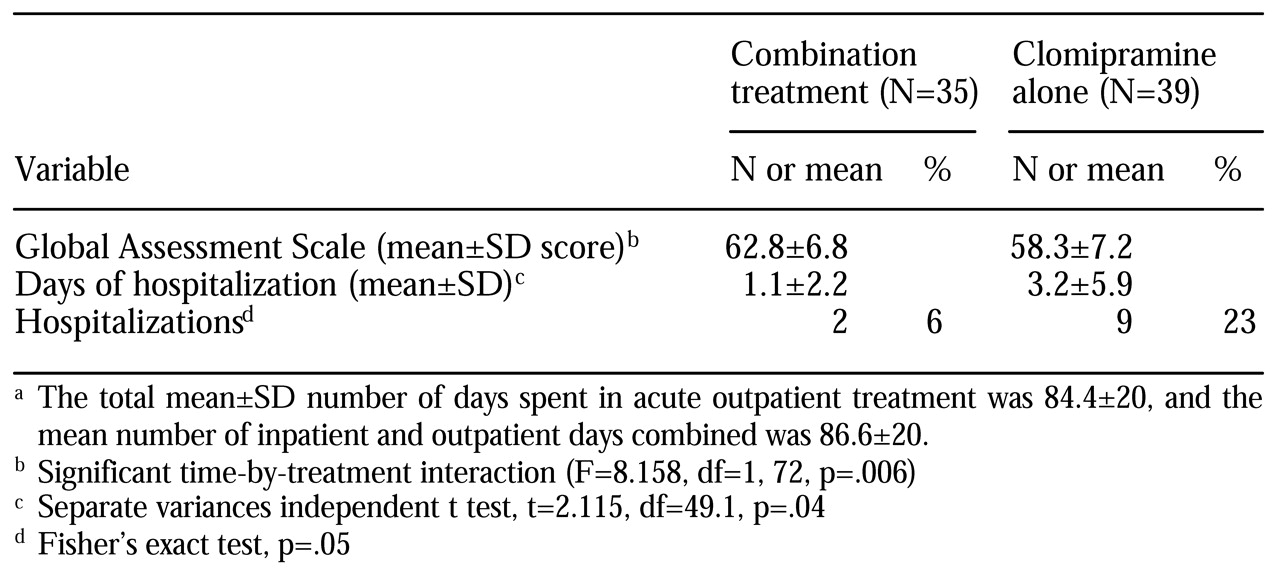

15). In addition, three experienced psychiatrists administered the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) at intake and at discharge. The number of days of hospitalization and sick leave were recorded by independent psychologists. The intraclass correlation coefficients were .79 for the HDRS, .76 for the GAS, and .93 for assessment of major depressive episode. The HSRS scores were rated by consensus.

All raters were independent. The nurse therapists and the members of the clinical staff did not participate in the outcome assessments. The psychologists who made the assessments of hospitalizations, number of days of hospitalization, number of days of sick leave, and GAS scores were blinded to each patient's treatment assignment. Blinding is difficult to maintain in the case of patients receiving intensive care in a general psychiatry service, so the individuals who rated the presence and severity of major depression and HSRS score at ten weeks were not blinded to treatment assignment.

Adherence to therapy was monitored by two psychologists through weekly one-hour sessions during which several treatment fidelity indexes were rated by consensus, including the adequacy of the treatment format, the treatment technique, and the process levels attained—nonspecific alliance, working alliance, insight, focusing, awareness, mourning, and reality reinvestment (

20). In this article, only adequacy of treatment is reported.

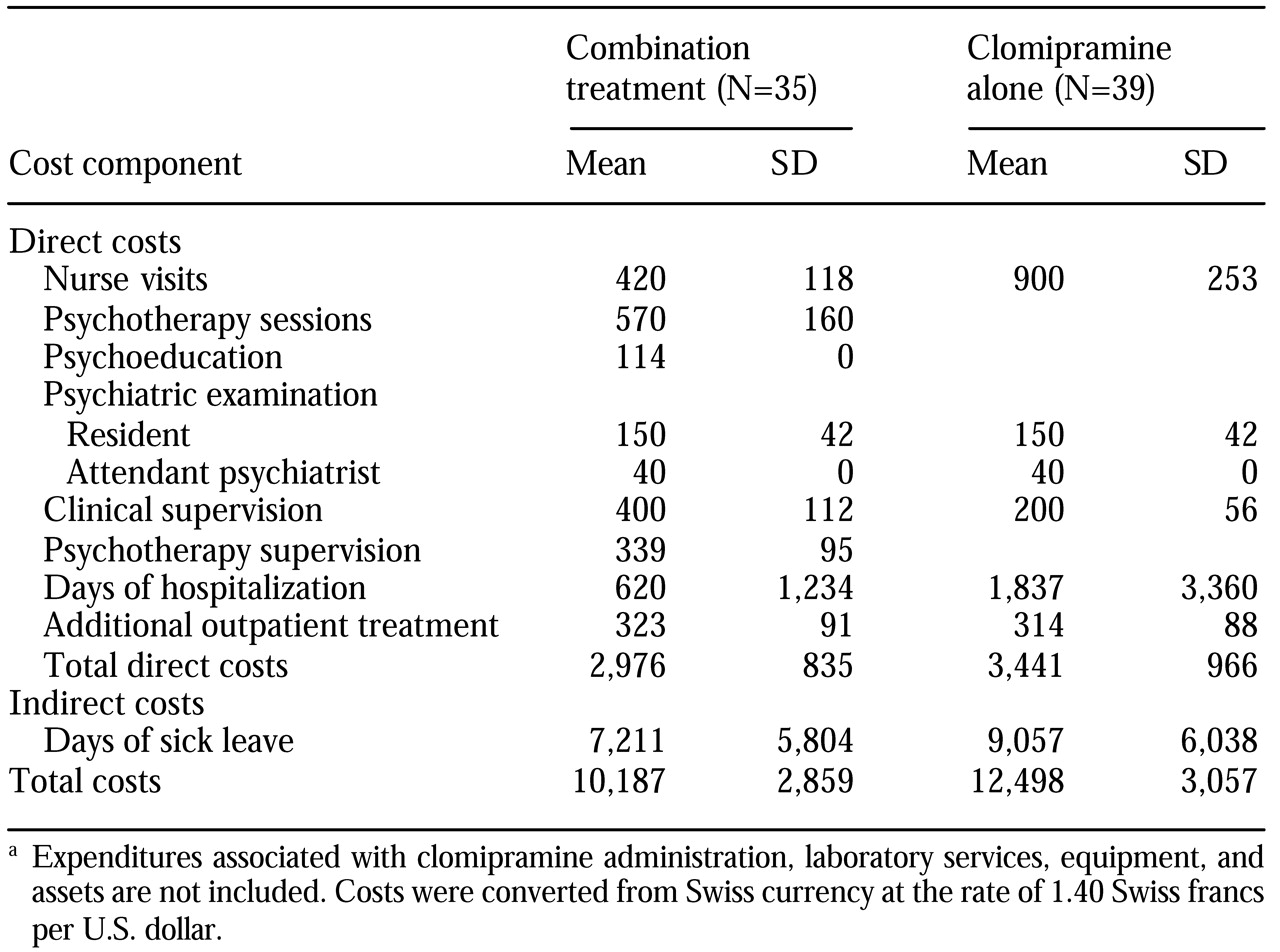

Clomipramine dosage schedules and plasma clomipramine concentrations were recorded on a compliance form. Unit costs were computed for each item of the treatment program. Expected expenditures (in U.S. dollars) for ten weeks of treatment were $2,012 for combined treatment and $1,270 for clomipramine alone, for an average daily cost of $29 and $18, respectively. We assumed that expenses for clinical supervision, clomipramine administration, laboratory services, equipment, and assets would be the same for both treatment groups. The indirect costs of loss of work days were computed on the basis of an average unit cost of $156 a day, which was developed by the economics and public health section of the Geneva Bureau of Statistics.

Data analysis

Point comparisons of the treatment groups were performed according to the metric characteristics of an a priori hierarchy of seven major outcome variables: hospitalization, number of days of hospitalization, whether the patient was in full remission (score of seven or less on the HDRS), treatment failure (persistence of a major depressive episode), severity of depression (based on HDRS scores), GAS score, and score on the "adjustment to work" subscale of the modified HSRS. Possible scores on this subscale range from 1 to 5, with lower scores indicating better adjustment. Changes over time were examined with repeated-measures analyses of variance, with type of treatment as a grouping factor. Analyses of covariance and two-way analyses of variance were used to control for age, gender, past major depressive syndrome, and global functioning at intake on the observed relationships between treatment choice and the main outcome variables. To control for intent to treat, the analyses were repeated with all 95 patients who had been randomly assigned to treatment.