Although there have been no extensive studies of the prevalence of alcohol abuse among American Indians and Alaska Natives, numerous reports document alcoholism as a major problem in this population (

1,

2,

3). In the general population, patients who abuse alcohol are overrepresented in primary care settings (

4). Seventy percent of persons who abuse alcohol make one or more outpatient visits for various health problems in any given six-month period; 90 percent of these persons are seen by a primary care provider (

4). Primary care patients who abuse alcohol tend to have a greater number of physical health problems (

5).

Despite the recent emphasis on managing psychiatric disorders in primary care settings and the problem of alcoholism in the American Indian and Alaska Native population, there are few data on the rate of alcohol use and abuse in this population. This study is the first to systematically investigate the prevalence of alcohol abuse among American Indian and Alaska Native patients in a primary care setting and to examine patient-related factors associated with alcohol use and abuse.

Methods

The study was conducted between April 1995 and May 1996 at the Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB), a multidisciplinary, community-based organization that provides comprehensive health care for the urban King County Native American population. SIHB patients represent about 250 tribes that vary greatly in acculturation, education, and income.

Persons aged 18 years or older were recruited from the SIHB waiting room to complete a 59-item self-administered survey. Of eligible patients, 70 percent (1,100 persons) agreed to participate, representing 25 percent of the entire eligible segment of the service population during the study period. No age or sex differences were noted between patients who participated in the survey and those who did not. The institutional review boards of the University of Washington and the SIHB approved the protocols, and participants provided written informed consent.

The 59-item survey elicited sociodemographic data and health information and also included a patient satisfaction measure, the Medical Outcomes Study six-item General Health Survey (SF-6), and questions about tribal affiliation and ethnic identity. Alcohol abuse was assessed with a three-item screening instrument based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Past studies indicate that this instrument has a sensitivity ranging from 87 to 91 percent and a specificity of 91 percent for alcohol abuse compared with

DSM-III criteria (

6). If the respondent endorsed any of the three items, he or she was considered to have screened positive for alcohol abuse. A research assistant obtained information about physical and mental health diagnoses and current medication regimens from participants' medical records.

Chi square analyses were used to examine differences between patients who screened positive for alcohol abuse and those who screened negative, and t tests were used to examine continuous variables. Only differences for which p was .01 or less were considered significant. Trend-level differences (p≤.05) were noted for descriptive purposes. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with alcohol abuse. Univariate logistic models, which controlled for age and sex, were constructed for each variable; only variables that were associated with alcohol abuse at a p value of .1 or less in these models were included in the logistic model. A trimmed model was constructed, assessed for fit with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and reported on the basis of a stepwise elimination procedure (

7). For the overall model, p values of .05 or less were considered significant.

Results

Of the 754 respondents, the majority were unmarried (520 patients, or 69 percent) and female (515 patients, or 68 percent). Their mean±SD age was 39.6±13.5 years (range, 19 to 90 years), and they had generally low levels of income, educational attainment, and employment. A total of 549 patients (73 percent) were enrolled tribal members, and 234 patients (31 percent) had a blood quantum—the total percentage of direct American Indian or Alaska Native ancestry reported by the patient—of at least 50 percent. For 231 patients (31 percent), tobacco use or abuse was noted in the medical record. Other common medical conditions were hypertension, obesity, and asthma. The types of health conditions, the average number of current medications, and the relatively low SF-6 scores we observed were to be expected in a sample characterized by a moderate burden of chronic illness.

Overall, 423 respondents (56 percent) screened positive for lifetime alcohol abuse. Of these, 383 (91 percent) answered two additional questions about whether the alcohol abuse had occurred within the previous year; 202 of the 383 respondents gave an affirmative response to at least one of these questions, which suggests a prevalence rate of current abuse of 27 percent for the sample of 754 patients.

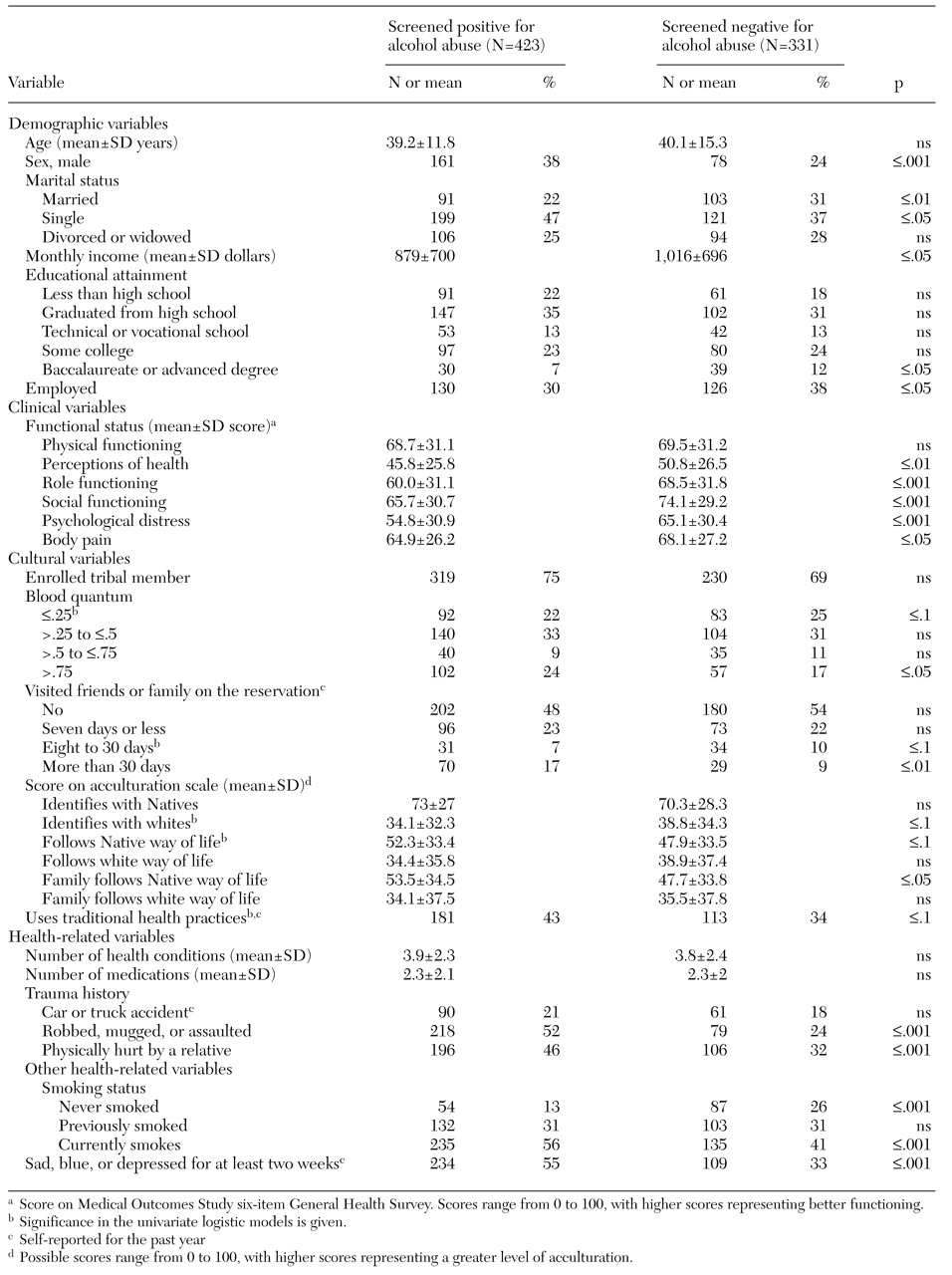

The survey results are summarized in

Table 1 by respondents' alcohol abuse status. Significance for the univariate logistic models is reported. Chi square and t tests confirmed the findings of the univariate analyses with the exception that no association was found between screening positive and body pain (t=1.58, df=1, p=.117 versus W=4.8, df=1, p≤.05), and an association was found between screening positive and use of traditional health practices (χ

2=4.52, df=1, p≤.05 versus W=3, df=1, p=.084).

Screening positive was significantly associated with being male, being unmarried, having a history of tobacco use or abuse as noted in the medical record, having been a victim of violence, reporting having been a smoker, being a current smoker, and reporting feeling depressed. The final logistic regression model for screening positive for alcohol abuse as opposed to screening negative was significant (χ2=83.37, df=25, p≤.001) and accounted for 23 percent of the variance. After baseline variables were controlled for, four variables were significantly associated with screening positive for alcohol abuse: male sex (W=4.5, df=1, p≤.05, odds ratio=1.92, 95 percent confidence interval=1.05 to 3.51); being single (W=5.7, df=1, p≤.05, odds ratio=2.45, CI=1.17 to 5.11); having ever been mugged, robbed, or assaulted (W=15.6, df=1, p≤.001, odds ratio=3.14, CI=1.78 to 5.54); and feeling sad, blue, or depressed for at least two weeks in the past year (W=5.3, df=1, p≤.05, odds ratio=2.03, CI= 1.11 to 3.70).

Discussion

In this study we observed a frequency of lifetime alcohol abuse of 56 percent and a frequency of current abuse of 27 percent. In previous studies, estimates of current alcohol abuse among outpatients in the general population (

5) and among American Indian and Alaska Native outpatients and inpatients (

3,

8,

9) range from 4 percent to 33 percent. In these other studies, the lowest estimates were based on self-report and the highest were derived from interviewer-administered screening protocols.

The high rate of positive screenings in our study may be attributable to several factors. First, previous studies have suggested that among American Indians and Alaska Natives, urban populations have a higher rate of alcohol use than rural populations, which have been the primary focus of past efforts (

9). Second, primary care patients may have a higher rate of alcohol abuse, because persons who abuse alcohol are more likely to have comorbid conditions for which they seek medical treatment.

Factors associated with screening positive for alcohol abuse in this study—being male, being single, having been a victim of violence, and feeling depressed—are well-recognized risk factors for alcohol abuse in the general population (

2,

3,

5,

9,

10). The results of our study suggest that violent victimization of drinkers may be a health consequence of alcohol abuse. Further studies of the consequences of victimization of drinkers and the identification of persons at risk in Native American communities are warranted.

A final finding that deserves comment is the low concordance rate (16 percent) between the clinicians' diagnosis of alcohol abuse and the screening results. The available data did not permit us to identify reasons for the clinicians' low rate of detection of alcohol abuse. However, cultural differences between physicians and Native American patients may play a role, and this issue deserves further inquiry.

This study had several limitations. Because of the nature of the sample, our findings cannot be generalized to other—particularly nonurban—clinics that serve American Indians and Alaska Natives. Moreover, the proportion of persons who meet the criteria for a diagnosis of alcohol abuse and dependence cannot be determined from a screening effort.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the potential magnitude of alcohol abuse among American Indian and Alaska Native patients in an urban primary care setting. The factors that were correlated with alcohol abuse were similar to those observed in the general population, but the nature and extent of the relationships and their temporal relationship to alcohol abuse need clarification. Although our results await verification, efforts to educate clinicians who work with Native Americans to improve the detection and management of alcohol abuse, as well as to identify barriers to and facilitators of this process, should be implemented immediately.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by grant 1P30AG-NE-15292 from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Nursing Research, grant 90-AM-0757 from the Administration on Aging, and grant P0143471 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Manson. The authors thank Ralph Forquera, executive director of the Seattle Indian Health Board.