Consensus is emerging that assertive community treatment is an evidence-based practice (

1). However, assertive community treatment has also been criticized, even by some members of the consumer movement (

2). For example, it has been said that assertive community treatment is paternalistic and has a tendency to overuse social and monetary behavioral controls and to overemphasize the role of medications.

Clients who are receiving assertive community treatment report greater satisfaction with treatment on global satisfaction measures than clients receiving usual mental health care (

3). However, except for one small study (

4), no published studies have specifically asked clients about whether they have any negative feelings toward assertive community treatment.

In this preliminary study we examined what clients like least about assertive community treatment and explored the impact on client dissatisfaction of a program's level of fidelity to the assertive community treatment model.

Methods

This analysis was part of a larger study of assertive community treatment at six community mental health centers in northeastern Indiana. Details about study setting, measures, and selection of the 249 clients who participated in the larger study have been reported previously (

5). The parent study was conducted from 1989 to 1992. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the larger study, and all clients gave written informed consent before being enrolled in the study. As part of an interview about client functioning that was conducted six months after enrollment in an assertive community treatment program, assertive community treatment workers asked clients 13 Likert-type questions about general satisfaction with services and an open-ended question about what they liked best about assertive community treatment (

6) as well as a question about what they liked least. The clients were not compensated for their participation.

Of the 249 clients in the larger study, 222 (89 percent) participated in the six-month interview. The number of usable responses for individual measures ranged from 166 (67 percent) for clients' ratings of compliance with medication regimens to 211 (85 percent) for case managers' ratings of clients' money management. A total of 187 clients (75 percent) responded to the question about what they liked least about assertive community treatment.

The clients typically provided one or two sentences in response to the question. The responses were recorded verbatim. Using a careful iterative process of grouping responses into similar categories (

6), we developed a code book that the second author used to classify responses into 21 categories. (A copy of the code book is available from the first author.) As an example, a response of "asks too many questions" would be coded as "assertive community treatment too intrusive," and a response of "sometimes hard to reach when needed" would be coded as "staff not available." Responses were assigned to multiple categories when appropriate.

In this study, a total of 182 clients (73 percent) provided usable responses. The responses of 50 clients (20 percent) were recorded as missing; five clients (2 percent) did not know what response to provide, did not understand the question, or refused to answer; another five clients (2 percent) gave responses that were not clear enough to allow coding, such as a response of "tobacco"; and seven clients (3 percent) were unavailable because they were hospitalized. For 175 clients the usable responses were coded into one of the 21 categories, and for seven clients they were coded into two categories.

Fidelity to implementation of the assertive community treatment model was assessed retrospectively at each site with the 17-item Index of Fidelity to Assertive Community Treatment scale (IF-ACT), which has been found to predict reductions in hospital use (

7). The IF-ACT scale ranges from 0, no implementation, to 1, full implementation.

Results

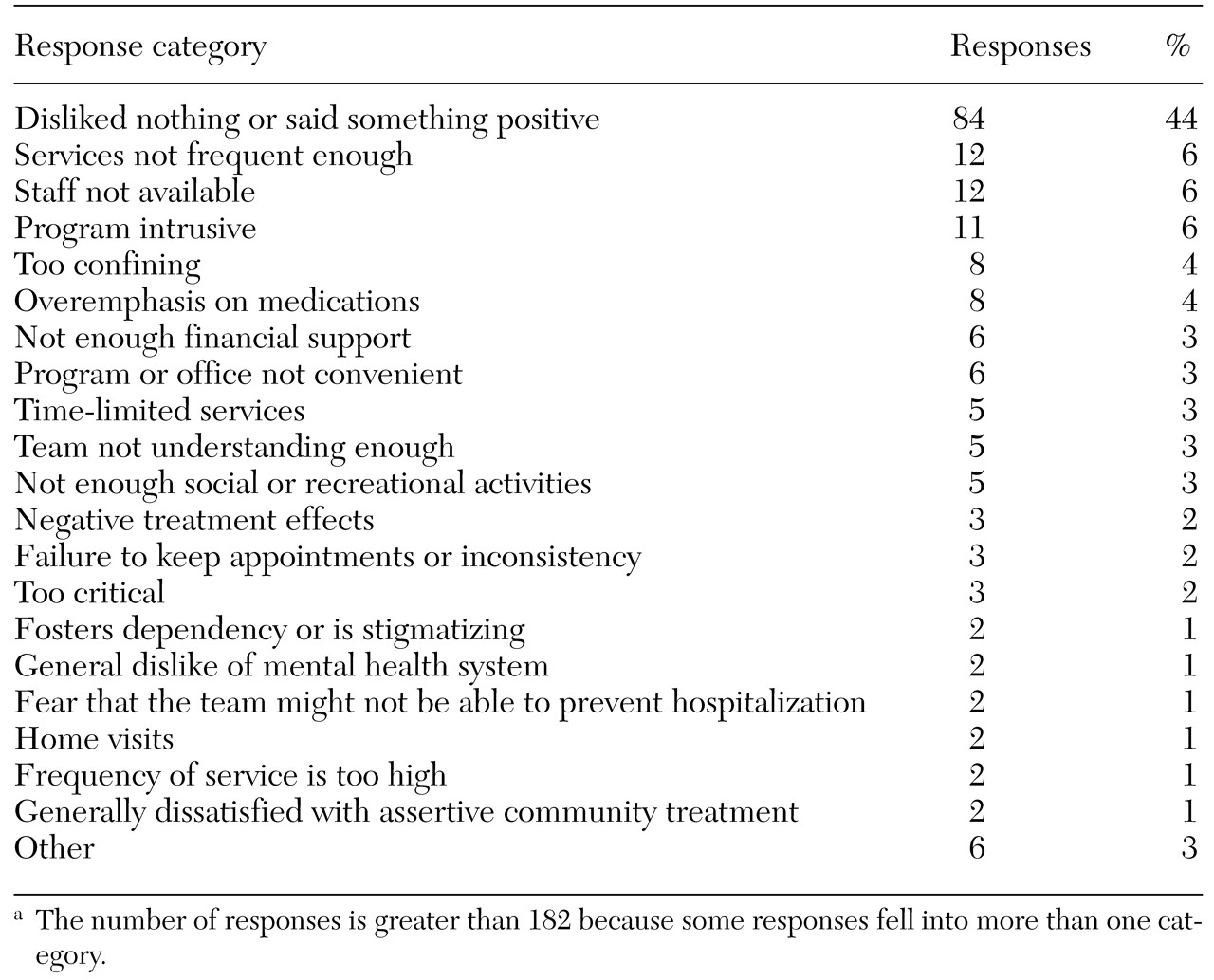

The 182 clients' responses to the question about what they liked least about assertive community treatment are listed in

Table 1. The most common response (44 percent of responses) was for clients to say that they disliked nothing about assertive community treatment or to make explicitly positive statements about this treatment approach. Of the five features of assertive community treatment that were most frequently rated as the least liked, three were features that have been criticized in the literature—intrusiveness (6 percent of responses), the confining nature of the program (4 percent of responses), and overemphasis on the use of medications (4 percent of responses)—and two were features that are considered to be characteristic of assertive community treatment but that respondents considered to be underimplemented—frequency of services (6 percent of responses) and availability of staff (6 percent of responses). All the analyses used responses as the unit of analysis. (Using respondents as the unit of analysis instead of responses did not materially change any of the descriptive or inferential results.)

To further examine the findings, we collapsed the 21 response categories into four supercategories. The first consisted of the most frequently mentioned single response category—disliked nothing or said something positive about assertive community treatment (84 responses, or 44 percent). The second supercategory (39 responses, or 21 percent) included responses that reflected dissatisfaction with elements that are considered to be characteristic of assertive community treatment, such as home visits, or that correspond to criticisms of assertive community treatment found in the literature, such as intrusiveness and overemphasis on use of medications. The third supercategory (30 responses, or 16 percent) included responses that reflected a perception of inadequate implementation of characteristic elements of assertive community treatment, such as frequency of services and availability of staff. The fourth supercategory (36 responses, or 19 percent) included responses that reflected dissatisfaction with aspects of mental health service delivery in general, not assertive community treatment in particular—for example, insufficient financial support and inconvenient location of the program or office.

To explore possible differences between sites, the six sites were divided into low-fidelity and high-fidelity programs in accordance with the method used by McHugo and colleagues (

8). Four sites were classified as low-fidelity programs (IF-ACT scores of .47, .48, .49, and .54) and two as high-fidelity programs (IF-ACT scores of .65 and .76). A significant difference in the distribution of responses was noted between the high- and low-fidelity sites (χ

2=15.9, df=3, p<.01). We conducted follow-up simple-effects chi square tests to determine whether particular response categories explained the differences in responses between sites.

Clients of high-fidelity programs were significantly more likely than those of low-fidelity programs to express no dislikes (65 percent compared with 36 percent; χ2=13.9, df=1, p<.01) and were significantly less likely to express dislike for elements specific to assertive community treatment (12 percent compared with 27 percent; χ2=5.1, df=1, p<.05) or to complain about underimplementation of elements specific to assertive community treatment (7 percent compared with 20 percent; χ2=4.8, df=1, p<.05). However, there was no significant difference between clients of high- and low-fidelity programs in their tendency to express dislike for general aspects of service delivery.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we attempted to answer the question of what clients like least about assertive community treatment. Somewhat surprisingly, about 44 percent of clients either said they could think of nothing they disliked or made a positive statement about assertive community treatment. In contrast, only 6 percent of these clients replied "nothing" when asked what they liked most about assertive community treatment (

6). However, most clients reported at least one aspect of assertive community treatment that they disliked. A minority mentioned negative features that seemed specific to assertive community treatment, such as home visits, or that had been criticized in the literature, such as intrusiveness.

Experts in assertive community treatment have noted that the treatment team must take full responsibility for the client's well-being while respecting and encouraging self-responsibility. Our results indicate that some clients think that the delicate balance between these sometimes contradictory objectives is not being achieved. That is, there appears to be a subgroup of clients who are dissatisfied with the "negative" paternalism and emphasis on medications associated with assertive community treatment, as reflected by feelings that this treatment approach is intrusive and confining and involves an excess of criticism.

Clients were almost as likely to express concern about the underavailability of core features of assertive community treatment—apparently wanting more of what assertive community treatment offers—as they were to express dissatisfaction with core elements of assertive community treatment—that is, wanting less of what assertive community treatment offers. These concerns about underavailability may reflect shortcomings in the implementation of assertive community treatment rather than in the program model itself. Consistent with this possibility, clients of high-fidelity programs were more likely to say that there was nothing they disliked about assertive community treatment, less likely to be critical of features specific to assertive community treatment, and less likely to be dissatisfied with the underimplementation of features of assertive community treatment that are considered to be characteristic of this treatment model.

One implication of these results is that criticisms of assertive community treatment may be concentrated among clients of poorly implemented assertive community treatment programs. The results also are consonant with the commonsense notion that clients who are receiving high-quality services, whether assertive community treatment or other types of services, are likely to report fewer dislikes about those services and with the observations that clients' complaints tend to be minimal in the presence of skillful assertive community treatment workers (

9).

This study had several limitations. Without a control group, we could not determine whether the respondents' dissatisfaction with assertive community treatment differed from their dissatisfaction with other treatment approaches. In addition, the fact that the data were collected by assertive community treatment workers may have made clients reluctant to make criticisms. A group format, for example, might encourage participants to be more frank about their opinions (

4).

However, biasing effects associated with the administration of the surveys by case managers rather than by independent raters or peers can be positive as well as negative and may be undetectable overall (

10). Moreover, any potential biases in this study should not have affected comparisons between sites, because the sites used identical administration procedures. The short period of enrollment in assertive community treatment services and the use of a single survey question are further limitations.