Certainly, with few exceptions, studies that have examined the prevalence of HIV seropositivity among persons with psychiatric disorders have found higher rates than those that would be expected in the general population. In a convenience sample of 971 psychiatric inpatient residents, 5.2 percent were seropositive (

5). In a sample of 118 psychiatric inpatients with co-occurring psychiatric and substance dependence diagnoses, 27 (23 percent) were seropositive. Although a history of intravenous drug use doubled the risk of seropositivity, a diagnosis of depression independently predicted seropositivity as well (

6). In a sample of 62 psychiatric patients in a shelter for homeless men, 12 (19 percent) were found to be seropositive (

7). At least five other studies using samples of more than 200 found seropositivity rates of 5 to 7 percent in psychiatric populations (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12).

Although these studies all suggest a high rate of comorbidity between HIV infection and serious mental illness, they share some methodological weaknesses that cloud interpretation of the findings. Most studies used convenience samples, and few compared the rates of seropositivity among persons who had psychiatric disorders with rates among persons who did not.

Despite a strong theoretical rationale for developing community prevalence estimates of HIV infection or AIDS among persons with serious mental illness, such studies are lacking. Without such data, it is impossible to estimate the relative risk of HIV infection among persons with serious mental illness or the relative risk of serious mental illness among persons with HIV infection or AIDS. This relative risk is important for several reasons. If the prevalence of HIV infection is higher among persons with serious mental illness than it is in the general population, then studies of the mechanisms of this additional risk and programs to reduce the risk are needed. In addition, if a significant portion of persons who are infected with HIV are also seriously mentally ill, then treatment programs for HIV infection and AIDS must have a strong psychiatric treatment component.

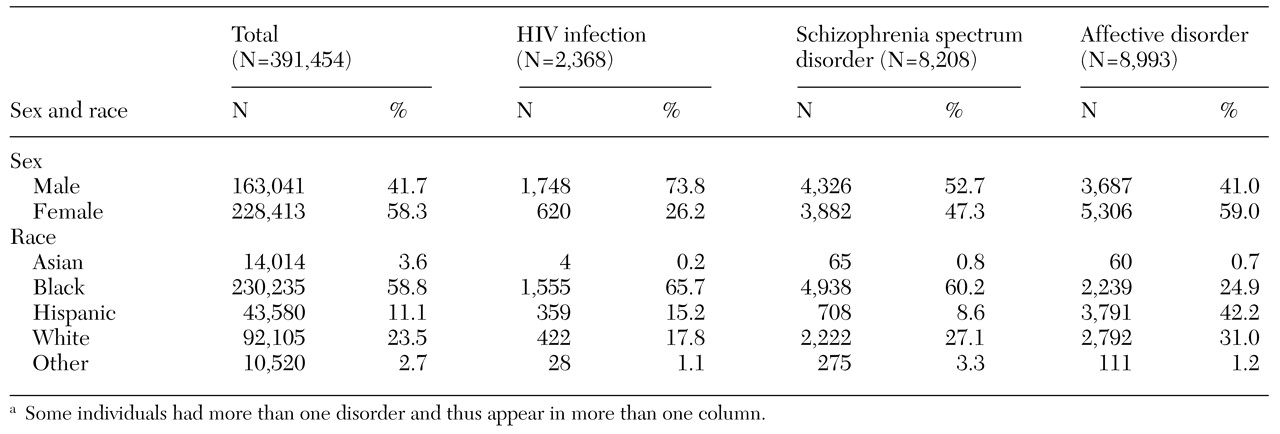

In this study, we had two hypotheses. The first was that the rate of HIV infection among persons with a diagnosis of a serious mental illness in the Medicaid population in Philadelphia would be significantly higher than the rate in the general Medicaid population. Our second hypothesis was that the rate of serious mental illness among persons with HIV infection would be significantly higher than the rate in the general Medicaid population.

Discussion and conclusions

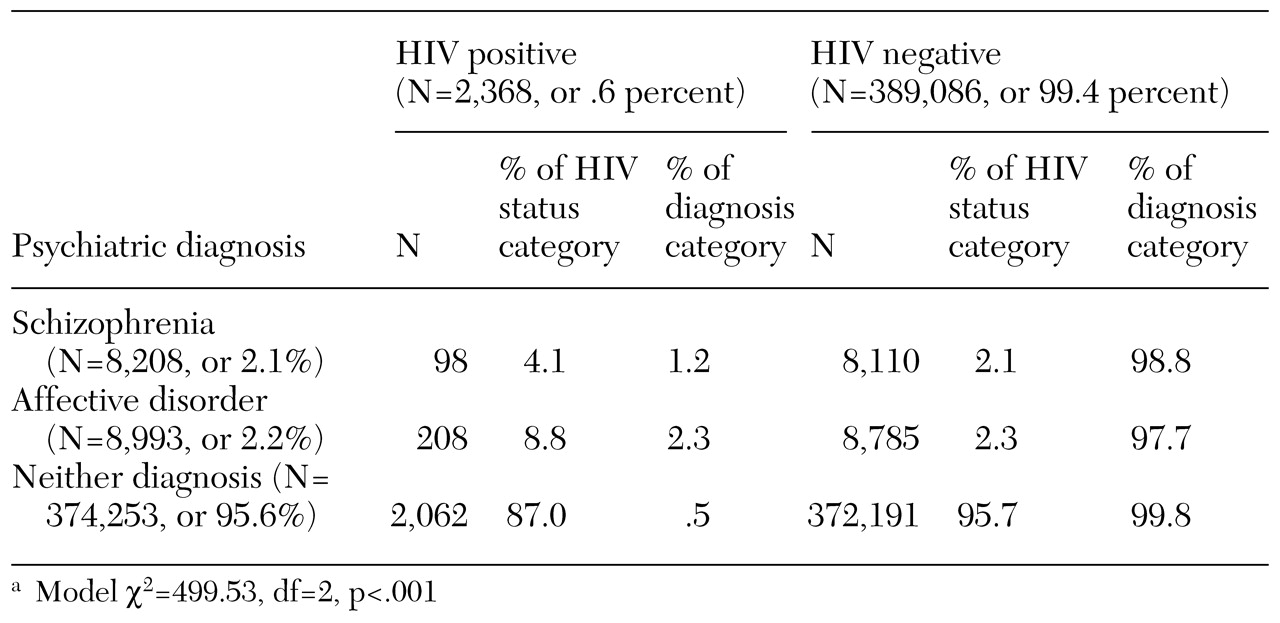

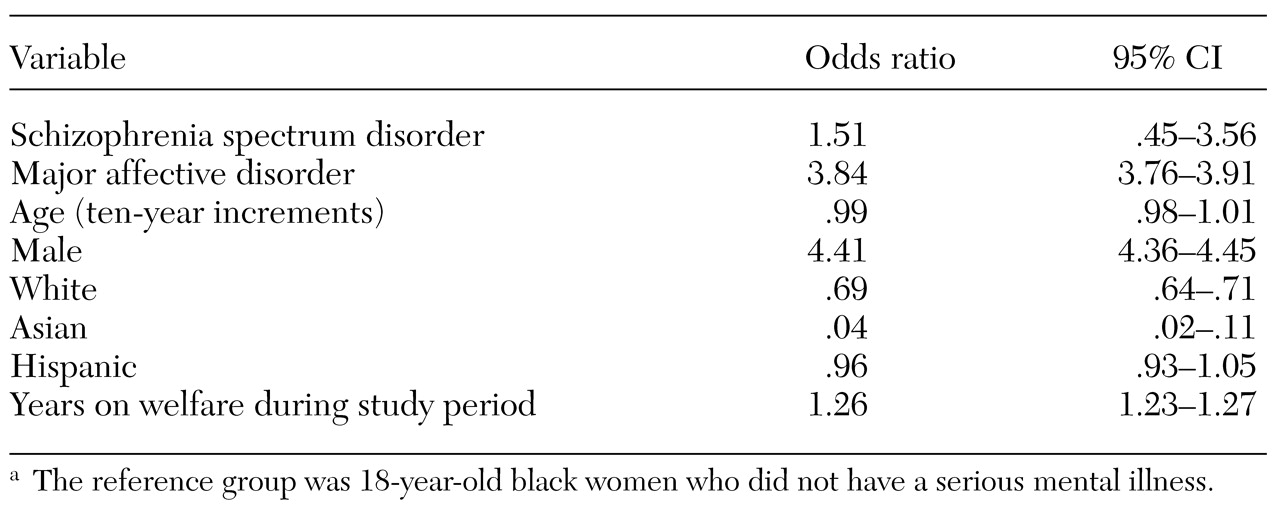

We found that persons on Medicaid with a diagnosis of serious mental illness were about five times as likely as the general Medicaid population to have received a diagnosis of HIV infection. We also replicated the results of other studies in finding that the risk of HIV infection was substantially greater for nonwhites, for persons living in more persistent poverty, and for men. A greater risk of HIV infection among persons with serious mental illness persisted after controlling for age, sex, race, and time on welfare. Although it is possible that seropositivity precedes or is causally related to the development of a major affective disorder, especially major depression, it is likely that schizophrenia and major affective disorders are risk factors for HIV infection.

We used an algorithm that called for the inclusion only of patients who had two outpatient claims or one inpatient claim for services within the specialty mental health sector (

17). We used this approach for several reasons, one of which was to replicate and extend the study by Walkup and colleagues (

15). If we had instead used any diagnosis of serious mental illness by any type of provider, and if misdiagnosis by nonspecialists is associated with drug use, then we would have artificially inflated estimates of comorbidity, because drug use is an independent risk factor for HIV infection.

Our results were similar to those of the study of New Jersey Medicaid claims by Walkup and colleagues (

15). In that study, the estimated treated prevalence of serious mental illness among persons with HIV infection or serious mental illness was 12.5 percent, which is similar to the treated prevalence of 12.3 percent that we found, providing evidence of the robustness of the finding. Walkup and colleagues did not publish the percentage of diagnoses of HIV infection among persons with serious mental illness and did not present a denominator of all Medicaid-eligible individuals, so it is not possible to compare their rates directly with ours.

There are several possible explanations for the strong associations between HIV infection and serious mental illness, and they are not mutually exclusive. Mental illness may be causally related to HIV infection. As we have already suggested, persons with serious mental illness may be more likely to engage in behaviors that place them at high risk of becoming infected with HIV, primarily substance use and high-risk sexual behavior (

4). It is also possible that the social marginalization and stigma associated with serious mental illness places persons who have these disorders in proximity to others who engage in high-risk behaviors. Thus, even if the behaviors of persons with serious mental illness are no riskier per se than the behaviors of others, these individuals could be engaging in those behaviors in the company of a group of individuals who have a higher rate of seropositivity.

It is also possible that HIV infection causes serious mental illness. There is evidence that seropositive status, while related to recurrence of previously existing major affective disorders, can also be related to the onset of those disorders (

18). There is also some evidence that HIV infection may trigger a psychotic episode and can contribute to first-onset schizophrenia (

19). However, these effects are small and could not account for the magnitude of the associations we observed in this study.

Estimates of the large number of undiagnosed cases of HIV infection notwithstanding, two sets of limitations to our prevalence estimates must be considered. The first set relates to the validity of calculating rates of treated disease and infection from Medicaid claims. There are at least four reasons why estimates of true prevalence based on estimates of treated period prevalence gleaned from Medicaid claims are lower-bound estimates.

First, it is likely that some Medicaid-eligible individuals with either serious mental illness or HIV infection did not receive any treatment and thus were not correctly represented. Second, Medicaid-eligible individuals may have received medical services through community clinics that were not billed to Medicaid. Thus some patients in our sample may have received psychiatric or HIV-related treatment or both without those claims appearing in the Medicaid data set. Third, individuals may have received treatment that was paid for by Medicaid before or after the study period without receiving treatment during the study.

Fourth, claims data were available only for individuals who were enrolled in a fee-for-service plan. A proportion of persons who were eligible for Medicaid in Philadelphia were enrolled in health maintenance organizations for at least part of the study period and may have received treatment for a target condition during that time. These individuals were all included in the denominator as not having received treatment for a target condition, because many individuals move back and forth from fee-for-service plans to health maintenance organizations, and no tenable statistical models are currently available to account for this movement in and out of the risk group. However, it is likely that this fourth threat to validity is smaller than the other three, because there is an incentive for individuals who have potentially higher treatment costs to remain in or return to the fee-for-service plan.

On the other hand, a second set of limitations could positively bias the estimates of risk of co-occurrence of HIV infection and serious mental illness. It may be that individuals with both diagnoses are more likely to come into contact with the health system as a function of their co-occurring disorders. It is also possible that persons who have serious mental illness are more likely to be tested for HIV infection, or vice versa, as a function of their contact with providers. This form of bias is often referred to as hospital bias or Berkson's bias (

20).

Berkson described this bias as arising from the fact that individuals with two conditions may seek treatment for either one, thus increasing the probability that they will come into contact with the health care system and be diagnosed as having the other condition. Therefore, prevalence estimates of a second condition that are gleaned from a treated sample are likely to overrepresent both the second condition and the co-occurrence of the two conditions in the general population. A number of studies have found higher rates of comorbidity in treated populations than in untreated populations for both psychiatric disorders (

21,

22,

23) and physical health conditions (

24,

25,

26).

For this bias to have had a significant impact on our estimates, persons with a serious mental illness as well as HIV infection would have to have been more likely to seek treatment as well as more likely to be diagnosed as having the other condition once they were receiving treatment for the first condition. Although we are aware of no studies that have examined the impact of either HIV infection or serious mental illness on help seeking, one study found that persons with alcoholism were more likely to seek treatment if they had co-occurring physical conditions (

23). However, the presence of the physical condition did not increase the likelihood that the patient would receive an alcohol-related diagnosis.

Certainly, other studies have suggested that the sensitivity of general health professionals to psychiatric disorders is limited (

27,

28), and confidentiality constraints between physical and mental health settings as well as limits on the availability of resources in mental health settings may preclude HIV testing in psychiatric treatment. Therefore, although these biases may have been present in our study, it is unlikely that they were of sufficient magnitude to account for the robust association between HIV infection and serious mental illness that we found.

The limitations we have discussed relate primarily to problems inherent in any study that uses claims data. Despite these limitations, useful epidemiologic studies can be accomplished by using claims. Welfare recipient data and Medicaid claims data provide large samples and specific information about relatively understudied populations and questions. Claims data probably provide more accurate and unbiased information than self-reports, especially in the case of sensitive topics such as HIV infection and serious mental illness in marginalized populations. Despite the inherent limitations, our findings have important clinical and policy implications.

The treated period prevalence of HIV infection is much higher among Medicaid enrollees with a serious mental illness than in the general Medicaid population. It is likely that persons with serious mental illness engage in behaviors that put them at greater risk of HIV infection. It is also possible that as a result of cognitive and perceptual limitations and distortions caused by the disorder, persons with serious mental illness require different primary prevention strategies to reduce their risk of contracting HIV.

Other issues bear exploration as well. If providers think that persons with serious mental illness are less likely to adhere to treatment, they may be less likely to prescribe a state-of-the-art treatment regimen—such as highly active antiretroviral therapy—for these individuals than for patients who do not have serious mental illness. At least one study has shown that persons with psychiatric disorders are less likely to receive state-of-the-art treatment for physical health problems such as myocardial infarction (

29). It is important to explore this issue in relation to HIV infection.

There is no evidence that adherence to treatment for HIV infection is poorer among persons with serious mental illness than in the general population. In fact, in a comprehensive review, Cramer and Rosenheck (

30) argued that observed differences in treatment adherence between persons with serious mental illness and other persons are small and may be due to measurement error. They concluded that improvements in methods for measuring treatment adherence in psychiatric populations are needed to determine whether true differences exist. No studies have compared adherence in psychiatric populations of persons who have co-occurring physical health conditions with nonpsychiatric populations of persons who have the same physical health problems.

Conversely, poorer treatment adherence among persons with serious mental illness could lead to poorer outcomes and the development of treatment-resistant strains of HIV in this population.

Of special note is the fact that more than 12 percent of persons who had a diagnosis of HIV infection also had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a major affective disorder. This large proportion suggests that programs to help persons with HIV infection manage the disease should contain components that address both psychiatric and physical concerns. It is especially important to establish open channels of communication between specialty mental health and general health care sectors to meet the joint needs of this population.

Finally, persons with both serious mental illness and HIV infection require special consideration because of the nature of the two conditions. Case managers must be trained to address the often competing needs of HIV infection and serious mental illness and especially in the management of two complex drug regimens. Research should be conducted into potential interactions of these therapies.

Further studies are needed to determine the modes of transmission and the potentially unique needs of this population in reducing risk and improving treatment.