Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood psychiatric disorder (

1) for which evidence-based pharmacological and psychosocial treatments have been developed (

2,

3,

4,

5). The short-term efficacy of stimulant medication treatment in particular is well supported by more than two decades of research (

2,

6,

7). Nevertheless, for many families pharmacological treatment for childhood ADHD remains controversial (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12). Reluctance among parents to have their child receive stimulant medication may contribute to their seeking nontraditional treatments (

13,

14,

15,

16), even though none of these treatments merit a scientific rating as an established treatment for ADHD (

16,

17).

Estimates of the use of nontraditional treatment—also referred to as complementary and alternative medicine—among children range from 9 percent to 46 percent and vary by type of treatment, study population, time period, and geographic region (

15,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22). Common nontraditional treatments for children include elimination diets, dietary supplements, herbal regimens, homeopathy, massage, acupuncture, and biofeedback (

18,

23,

24). Religious approaches, such as faith healing, may also be a used as an alternative intervention for childhood behavioral problems (

25). To our knowledge, only one study has examined nontraditional treatments for ADHD. In a clinical sample of 290 Australian children with ADHD, 64 percent had received alternative therapies, the most common of which was the use of special diets (

26).

The prevalence and patterns of use of alternative medicine for children with diagnosed or suspected ADHD have several important clinical and health policy implications. Parents who suspect that their child has ADHD may elect to use nontraditional interventions without obtaining a professional diagnostic assessment, which may mean that the child will receive treatment that is not clinically indicated. Additionally, if alternative medicine is used in lieu of established treatments, parents may not have the opportunity to receive recommended patient education about effective treatment options and the adverse effects of delaying care (

27).

Clinicians also need to be aware of nontraditional interventions in order to develop treatment plans that address potential drug interactions with natural remedies, such as the effect of St. John's wort on the metabolism of prescription medications, and to identify potential risks of specific alternative medicine interventions, such as neuropathy as a consequence of megavitamin therapy (

28,

29). Moreover, because nontraditional treatments are not addressed in professional ADHD practice guidelines or parameters (

27,

30,

31,

32), these sources provide no guidance on the clinician's role in eliciting information on use of complementary and alternative medicine or in counseling parents on the efficacy or potential harm of such interventions.

The objectives of this study were threefold: to describe the use of four types of complementary and alternative medicine—chiropractic, homeopathy, massage, and acupuncture—and of faith healing for symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, or poor concentration; to examine whether use of these approaches varies with parental concerns about ADHD; and to identify potential independent predictors of nontraditional interventions, such as sociodemographic characteristics, parents' knowledge about ADHD, and the severity of symptoms. Parental concern was examined because it is related to the detection of behavioral disorders and help-seeking behavior (

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38). We hypothesized that nontraditional treatment is more common among children whose parents suspect a diagnosis of ADHD than among children whose parents have general concerns about their child's behavior, activity level, or attention span.

Methods

Sampling

School registration records were used to identify 12,009 elementary school students enrolled in kindergarten through fifth grade during the 1998-1999 academic year in a north central Florida public school district. A gender-stratified random sampling design was used to oversample girls by a margin of two to one to ensure adequate representation. A total of 3,158 students were selected by this means.

Only one child per household was eligible for the study to ensure subject independence. Children were eligible if they lived in a household with a telephone, were not receiving special education services for mental retardation or autism, and were Caucasian or African-American. Children from other ethnic groups were excluded because they accounted for less than 5 percent of the total student population. More information about the sample has been published elsewhere (

39).

Procedures

Informed consent was obtained in procedures approved by the institutional review board of the University of Florida and the school district research director, and telephone interviews of parents were conducted from October through December 1998. The interview included inquiries into the child's health status and use of health services, the parent's knowledge and attitudes about ADHD, and standardized child behavior ratings. After the interview, permission was sought to ask the child's homeroom teacher to complete similar child behavior rating scales.

Participation

Contact was made with 2,035 parents, or 64 percent of the sample. Seventy-nine percent of these agreed to participate, yielding 1,615 completed interviews. Parental permission to administer teacher behavior questionnaires was obtained from 1,549 (96 percent) of the respondents, and questionnaires were mailed to homeroom teachers. Of these, 1,187 (77 percent) were completed and returned.

Measures

Levels of ADHD-related parental concerns. Children were assigned to one of four mutually exclusive categories on the basis of their parents' responses to 26 survey questions assessing ADHD detection and use of services: diagnosed ADHD, suspected ADHD, general behavioral concerns, and no concerns. Parents were asked whether they had any general concerns that their child may have an emotional or behavioral problem, including overactivity, impulsivity, inattention, or poor concentration; whether they suspected that their child had ADHD, attention-deficit disorder, attention deficit, or hyperactivity; whether school staff had voiced general concerns or suspicions of ADHD; and whether their child had ever had a professional evaluation for ADHD.

If the child had received a diagnosis of ADHD by a professional, he or she was categorized as having "diagnosed ADHD." A child was categorized as having "suspected ADHD" if the parents or school staff suspected ADHD but no diagnostic assessment had been sought. If the parents or school staff had concerns about the child's emotions or behavior—that is, activity level, impulsivity, inattention, or poor concentration—but no suspicion of ADHD, the child was placed in the "general behavioral concerns" category. The remaining children were in the "no concern" category. Together, children in these first three categories were considered to be at risk of having ADHD.

Child and parent characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, race, and lunch subsidy status, were obtained from school district administrative records. Lunch status, which is based on federal government guidelines involving family income, was identified as subsidized and nonsubsidized, with subsidized lunch status corresponding to lower socioeconomic status (SES). SES scores were also calculated with the Hollingshead four-factor index, which can range from 8 (lowest social stratum) to 66 (highest) (

40).

Parents' knowledge about ADHD was assessed with survey questions designed to serve as indicators of general familiarity with ADHD for nonclinical populations and modeled after the AIDS knowledge and attitudes section in the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (

10,

41).

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had ever heard about attention-deficit disorder, hyperactivity, ADD, or ADHD and to describe the recency and amount of their knowledge of ADHD as well as the information sources on ADHD they used most commonly (for example, the Internet). The questions also probed beliefs about the role of sugar as a causative agent and of medications as a possible treatment for ADHD. A knowledge summary score was constructed, ranging from 0, least amount of knowledge, to 5, highest amount of knowledge. In a previous study with participants of similar sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge summary scores had a normal distribution (mean±SD= 2.6±1.6, median=3) (

10). Internal consistency (coefficient alpha) was .73, and test-retest agreement of the individual survey questions ranged from 73 to 100 percent (N=59) (

10).

The severity of behavioral problems was assessed with parent and teacher report forms of a standardized screening measure, the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, version IV (SNAP-IV) checklist, which is a rating scale consisting of operationalized

DSM-IV criteria for ADHD (

42). The internal consistency of the original SNAP was reportedly high (greater than .9 for all symptom clusters), and two-week test-retest reliability was .7 for inattention items, .8 for impulsivity items, and .9 for hyperactivity items. Norms have been established for the SNAP for boys and girls of elementary school age for average ratings per item (

42). Scores that are two standard deviations above the norm indicate severe symptom levels.

Traditional and nontraditional treatments. Parents whose children fell into the categories of diagnosed ADHD, suspected ADHD, or general behavioral concerns were asked about lifetime use of both traditional and nontraditional treatments. For children currently receiving traditional treatment, parents indicated the type of provider and treatment modalities used.

A child was identified as having received a nontraditional treatment modality if the parent answered yes to the question "Have you ever used any of the following to help your child with hyperactivity, impulsivity, or concentration problems: chiropractor? massage therapy? homeopathic therapy? acupuncture? faith healing?" The first four of these types of nontraditional treatment were selected on the basis of literature reports of their common use in child populations (

15). In addition, school administrative data were used to determine whether children received exceptional student education services.

Data analysis

The procedure outlined by Aday (

43) was used to adjust estimates for sampling and nonparticipation effects. This process was made possible by the availability of administrative data (gender, race, lunch subsidy status, and special education category) for all eligible students. In the first stage of weight development, an expansion weight (the inverse of the selection probability) was computed for each subject, adjusting for disproportionate sampling. The expansion weight calculation depended on the child's gender and the number of eligible children in a household.

In the second stage of weight development, 12 weighting classes were formed on the basis of factors for which a significantly different response was noted; these included race, lunch subsidy status, and special education service status (

44). To adjust for differential response rates, the expansion weight was divided by the response rate within each weighting class to form a response-adjusted weight.

In the third stage of weight development, a relative weight was constructed by dividing each response-adjusted weight by the mean response-adjusted weight. This scaling step effectively downweighted the number of subjects to equal the actual sample size. The final weight was obtained after trimming of the extreme (the upper and lower 1 percent) values of the relative weights and uniform redistribution of the values so that the actual sample size was preserved.

Bivariate analysis was conducted with a chi square test of proportions for discrete variables and analysis of variance procedures for continuous variables. As part of the latter procedure, pairwise comparisons using the Scheffé estimation technique were conducted (alpha=.05). This procedure was selected because it allows multiple comparisons to be made simultaneously and it remains valid under a wide range of conditions (

45). Stepwise regression analysis with an F-to-stay of 3.92 was performed to examine the independent contribution of hypothesized predictor variables—including sociodemographic factors, parents' knowledge of ADHD, severity of children's behavioral problems, and parents' level of concern—to the likelihood that nontraditional treatment would be used for ADHD symptoms. SAS, version 6, and STATA were used to conduct the statistical analyses (

45).

Results

ADHD-related parental concerns

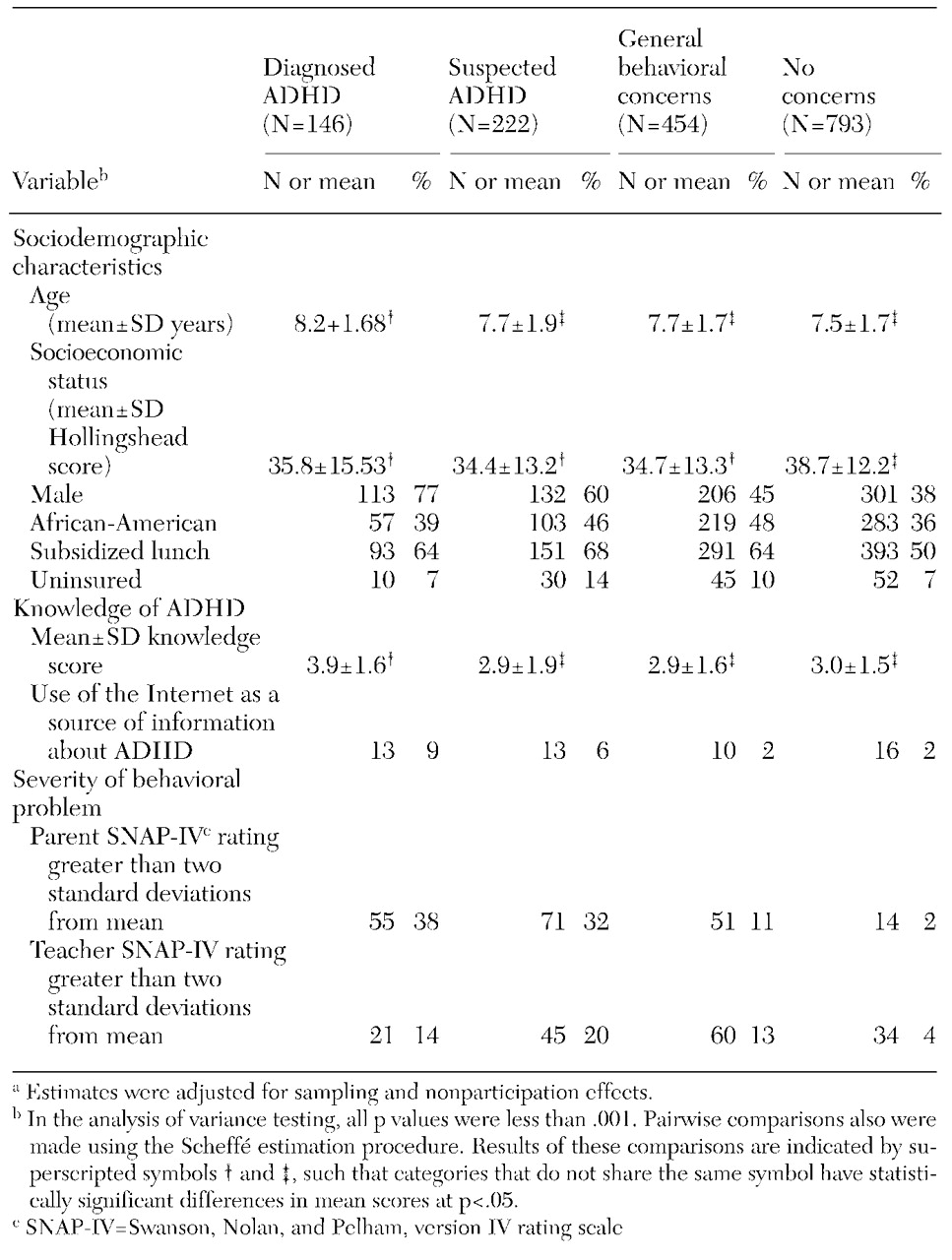

Table 1 summarizes the relationship of parents' concern about ADHD symptoms with the sociodemographic characteristics of the child and family, the parent's knowledge of ADHD, and the severity of the child's behavioral problem. The mean±SD age of the children was 7.7±1.74 years (range, five to 12); 41 percent (N=662) were African American. The mean SES score was 38.4±12.9 (range, 8 to 66, with higher values indicating higher socioeconomic status). Nine percent of the parents (N=146) reported that their child had a diagnosis of ADHD based on a professional evaluation, and ADHD was suspected in an additional 14 percent of the children (N=222). More than a quarter of the parents (N=454, or 28 percent) had concerns that their child had an emotional or behavioral problem, and 49 percent (N=793) had no concerns.

Traditional and nontraditional treatments

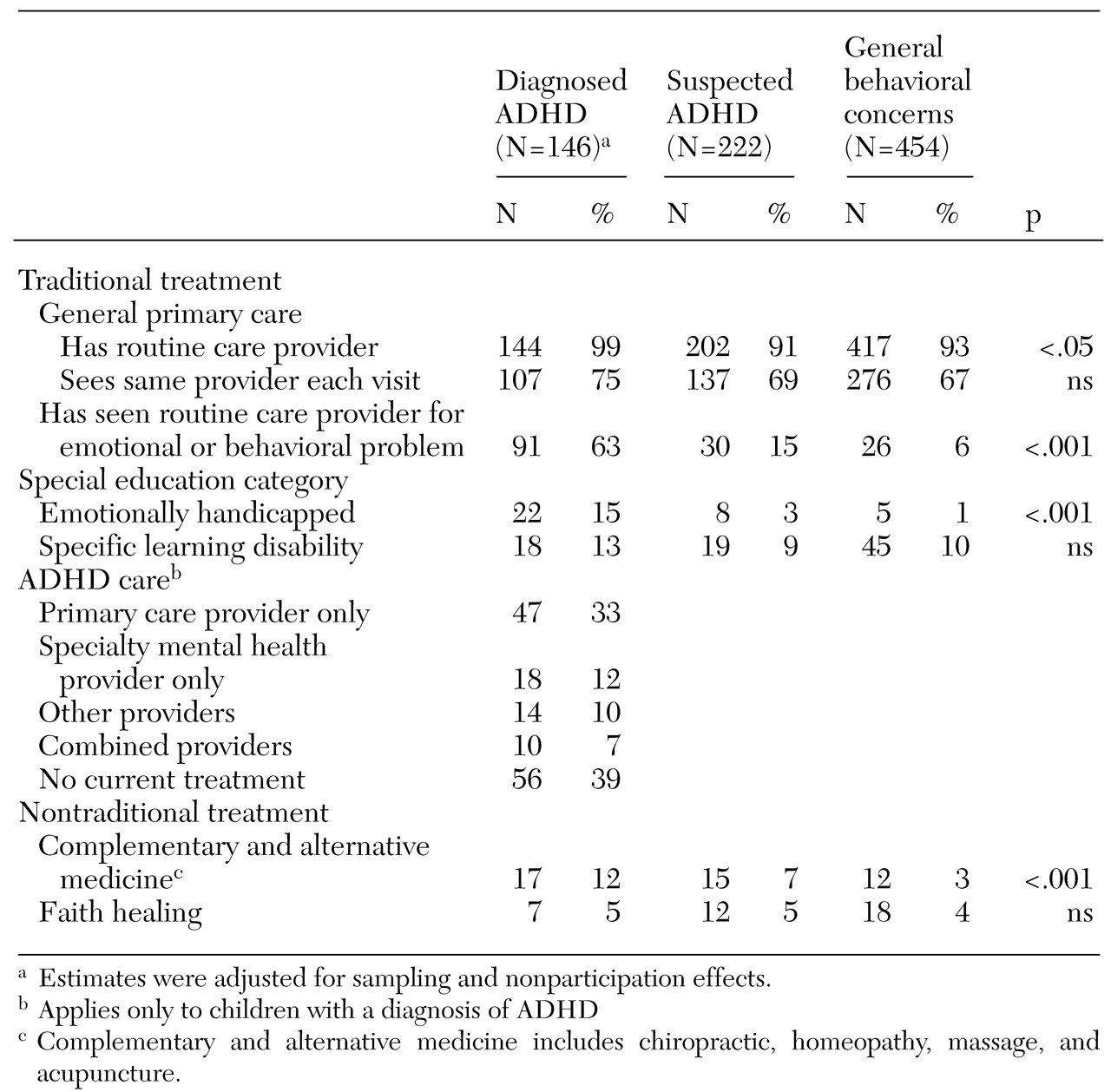

Table 2 summarizes the use of traditional and nontraditional treatments for behavioral problems among children with ADHD or at risk of having ADHD. Of particular note, while almost all children with a diagnosis of ADHD had a routine care provider and most of their parents (N=92, or 63 percent) reported discussing their concerns about ADHD symptoms with the clinician, 39 percent (N=57) were not receiving traditional ADHD treatment.

Among the 822 children with a diagnosis of ADHD or at risk of having ADHD, 5 percent (N=44) had used complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of ADHD symptoms. These interventions included homeopathy (N=24, or 3 percent), massage (N=20, or 2.4 percent), chiropractic (N=14, or 1.7 percent), and acupuncture (N=3, or .4 percent). Faith healing was reported by an additional 4 percent (N=37) of parents. Given that faith healing was rarely (.6 percent) combined with other alternative methods, it was treated as a discrete nontraditional treatment modality. Complementary and alternative medicine interventions, but not faith healing, varied by level of parental concern, such that children with a diagnosis of ADHD had the highest level (12 percent) of such interventions (p<.001).

Users of nontraditional interventions

As

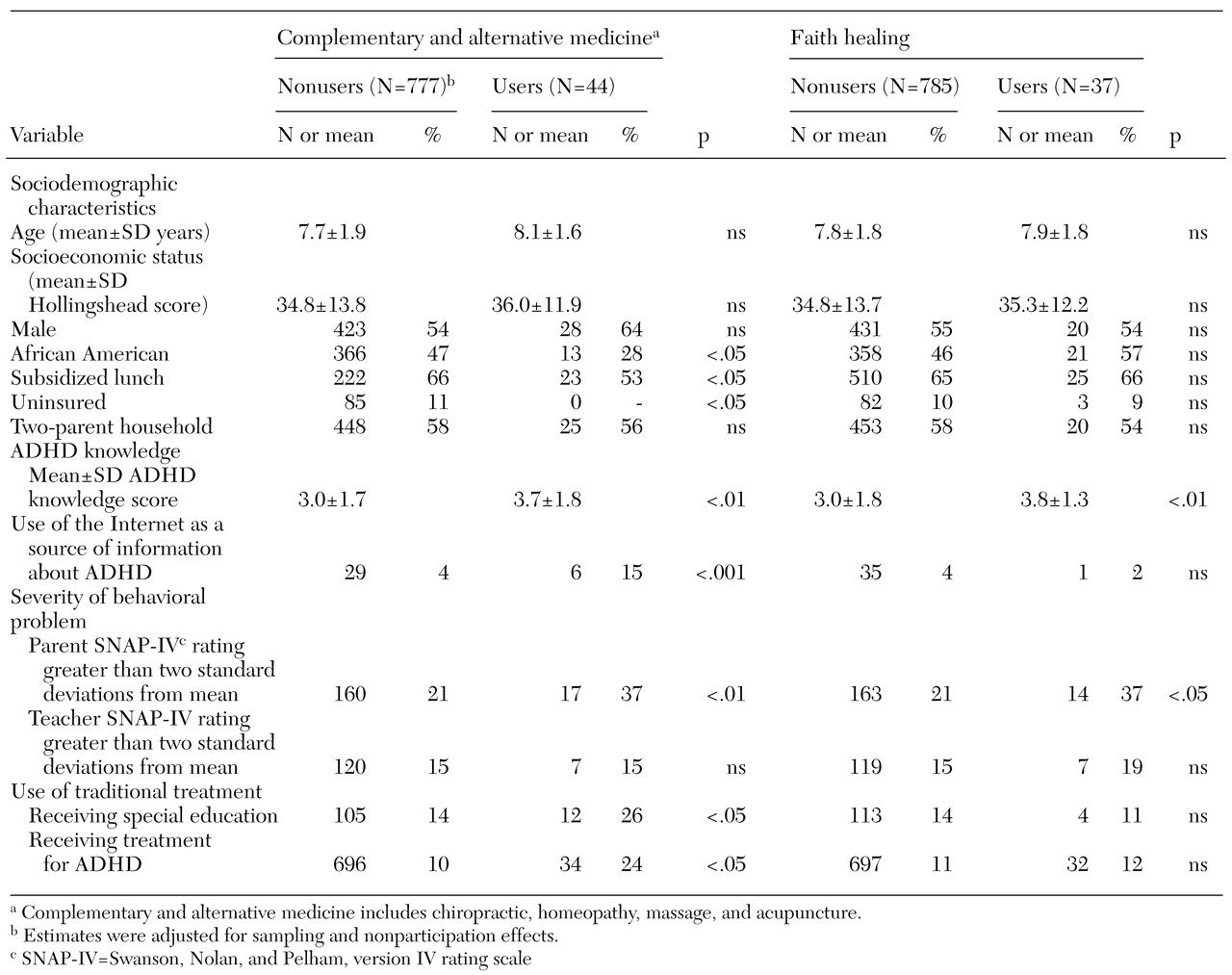

Table 3 shows, the sociodemographic characteristics of the child and family, indexes of parents' knowledge of ADHD, the severity of the child's behavioral problem, and use of traditional treatment were significantly related to use of complementary and alternative medicine. Children who received complementary and alternative treatments were more likely than those who did not to be Caucasian and covered by health insurance and less likely to be poor. The parents of these children had higher ADHD knowledge scores and more often used the Internet as a source of information about ADHD. Use of complementary and alternative medicine was also associated with greater severity of symptoms and with higher use of traditional services in primary care and special education. In contrast, use of faith healing was related only to higher ADHD knowledge scores and severity of symptoms.

In the stepwise regression model (pseudo R2=.07), three predictors of use of complementary and alternative medicine were retained. A diagnosis of ADHD had the largest effect size and the highest precision (odds ratio [OR]=4.5; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=2.1 to 9.6). Suspected ADHD, as compared with general behavioral concerns, was associated with twice the odds of such use (OR=2.4; CI=1.1 to 5.3), and use of the Internet for information about ADHD tripled the odds (OR=3.2; CI=1.3 to 8.2).

Discussion and conclusions

The overall estimate of use of selected complementary and alternative medicine for symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity, or poor concentration in this sample of elementary school students was substantially lower than that reported in the only other published study addressing complementary and alternative medicine use for ADHD (5 percent compared with 64 percent) (

26). This discrepancy may be explained by differences in the assessment of nontraditional treatment, because dietary interventions, which made up 94 percent of the alternative therapies in the earlier study, were not assessed in our study. However, the rate of use of complementary and alternative medicine in this school-based population was more similar to that reported for pediatric outpatients (11 percent compared with 5 percent) (

15). In that sample, chiropractic and homeopathy were the most commonly used methods, whereas the most popular method in our study was homeopathy, closely followed by massage therapy; the least commonly used was acupuncture.

We hypothesized that the high rate of homeopathy use may be related to several factors. Homeopathic preparations are available over the counter and do not require a visit with an alternative medicine practitioner, making it a less expensive choice than other interventions. Homeopathic preparations also may be seen as "natural" and less invasive than chiropractic or acupuncture, and thus may be more acceptable to parents for use with their children.

While scientific support of the efficacy of nontraditional treatments for ADHD has not been established, there is evidence that parents need to consider potential risks of such interventions. A recent review mentioned pertinent risks in all methods, even those commonly perceived as harmless, such as homeopathy (

29), reinforcing the notion that nontraditional treatments should be discussed with the child's traditional health care provider.

As we hypothesized, use of complementary and alternative medicine varied with the specificity of parental concerns. Even though the utility of parental concerns in the detection of developmental and behavioral problems has been well established (

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38), specific concerns about ADHD did not predict an eventual diagnosis in a clinical sample of children referred for school problems (

46). Thus the fact that 7 percent of children in whom ADHD was suspected had received nontraditional interventions without a professional evaluation and diagnosis should raise some concerns. Use of complementary and alternative medicine also was independently associated with parents' reporting using the Internet as a source of information about ADHD. This relationship may in part reflect the large number of scientifically unsubstantiated recommendations accessible through this medium and merits closer examination as a topic for inclusion in parent education sessions (

47,

48,

49)

Faith healing did not vary by level of specificity of parental concern and was rarely reported by parents who used complementary and alternative medicine. It was more commonly used for children with higher ADHD symptom ratings and by parents with higher ADHD knowledge scores, but its use did not vary by any other user characteristic. To our knowledge, no other study has addressed whether parents use faith healing methods as an alternative ADHD treatment for their children.

Findings from this study should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. The sample was restricted to one geographic region in north central Florida, and the results therefore may not be generalizable to other areas. Parents' reports of a clinical diagnosis of ADHD were not validated with survey information from health care providers or with review of health records. This study was also limited to four types of nontraditional interventions and to faith healing. Dietary measures were not included in this survey because a second phase of the study examined self-care measures, including dietary manipulations, in greater detail. Finally, the relatively low rate of use of complementary and alternative medicine limited our ability to detect significant relationships in this study.

Nevertheless, the study's findings suggest that nontraditional treatments for ADHD symptoms merit further study. Future research should examine the full array of potential complementary and alternative medicine services, including interventions that contain commonly available regional medicinal plants, and should be geographically more diverse to allow broader generalization of findings. Results of such studies could inform future editions of ADHD practice parameters on how to address nontraditional interventions. In the meantime, our findings indicate that health care providers should routinely inquire about the use of complementary and alternative medicine for children with ADHD or in whom ADHD is suspected. Parent education should not only address the evidence base of traditional therapies but also make reference to commonly selected nontraditional methods and comment on the limitations of the Internet as an information source.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants RO1-MH-57399 and R24-MH-51846 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Dana Mason, B.S., for research assistance.