Although advances in infectious disease research have led to increased awareness and prevention, some subpopulations, including individuals with severe and persistent mental illness, remain at greater risk of communicable diseases. A limited number of studies have investigated the prevalence of infectious diseases other than HIV within psychiatric populations. For HIV, the reported prevalence among persons with severe and persistent mental illness ranges from 4 to 23 percent (

1). Few published data exist on rates of positive tuberculin skin tests in psychiatric samples (

2). In addition, no large-scale studies of tuberculin or hepatitis A tests exist, and few investigations have examined the prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B and C in U.S. psychiatric populations (

3,

4,

5,

6).

The retrospective study presented here provides new data on the frequency of hepatitis A antibody positivity in an urban state psychiatric hospital as well as confirmatory evidence about rates and psychosocial risk factors for positive screening tests for tuberculin, HIV, and hepatitis B and C already described in the literature (

2,

5,

6).

Methods

The Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center (ELMHC) in Boston is part of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Annually, this state psychiatric hospital admits an average of 120 inpatients, referred either through the court system for forensic evaluations (95 percent) or through transfers from acute care hospitals for longer-term management. Upon admission patients meet with an infection control nurse who discusses risk factors for infectious diseases, coordinates testing, and delivers the results and counseling. Patients who test positive are referred for further medical evaluation, initially through an internist at the hospital and then through a primary care physician in the community after discharge.

Data were reviewed for the 655 patients who were admitted from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 1999. For patients with multiple hospitalizations during the study period, only the first admission was considered. Frequencies were calculated on positive tests for tuberculin, HIV, and hepatitis A, B, and C. HIV status was included if the patient was tested in the year before admission. Positive screens for tuberculosis and viral hepatitides did not necessarily indicate active disease or communicability. A subset of 128 charts from consecutive admissions in 1998 was further reviewed to identify the following risk factors: age, gender, education, immigrant status, homelessness, having a primary medical provider, Mini-Mental Status Exam score on admission, psychiatric diagnosis, history of drug use, and type of substances used—that is, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, and other drugs.

Standard statistical software packages (SPSS, StatXact) were used for all descriptive and inferential analyses. Binomial test procedures (that is, based on Z approximation and exact probabilities) were conducted to compare rates of infection in our sample with those in the U.S. general population. Logistic regression was used to identify risk factors for positive tests.

Results

Because not all patients who were admitted to the hospital were tested for each disease, we examined rates of positive tests both among patients who were screened and among patients who were admitted. The frequency calculations of positive tests among patients who were admitted included data from patients who were screened as well as those who were not tested; these calculations assumed that all of the unscreened patients had negative test results. Therefore, these frequency figures of the total sample reflect the lowest possible rates for positive test results for the different infectious diseases and likely underestimate the true occurrence of positive tests. We believe that this conservative estimate is more useful for comparing our data with that for the U.S. population estimates.

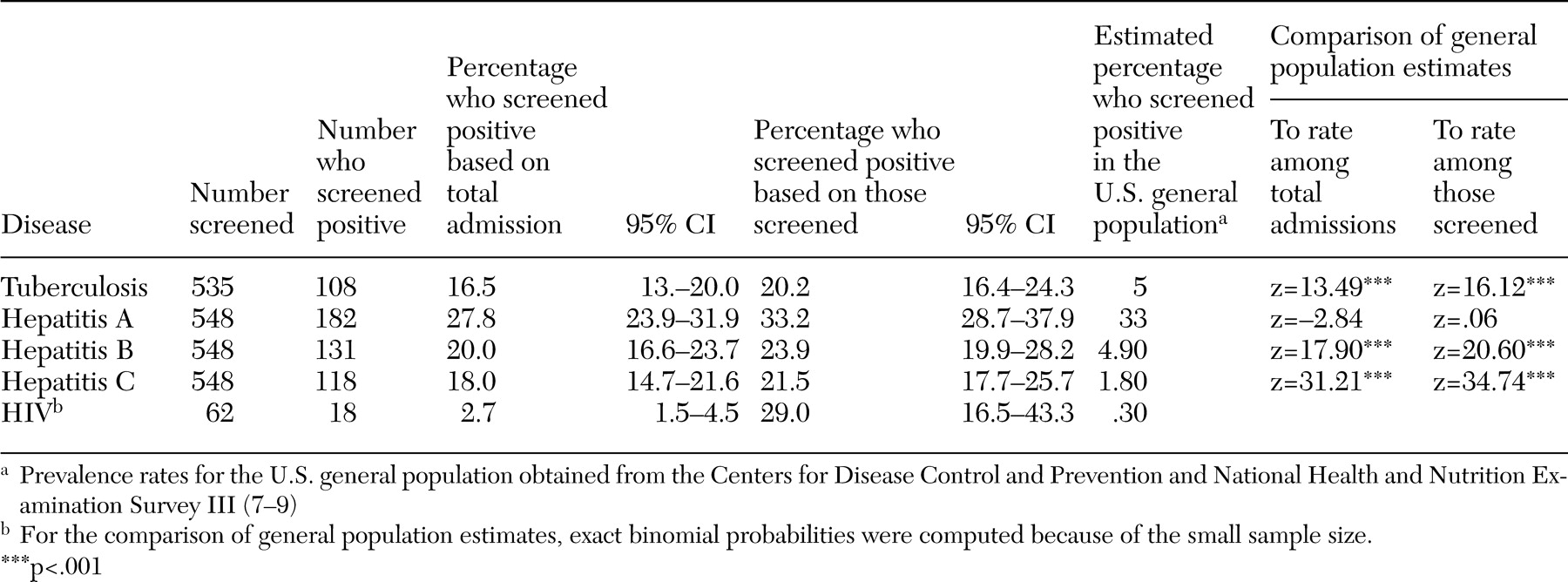

Table 1 details the frequency of positive tests for tuberculin, the hepatitides, and HIV. Except for hepatitis A, the estimates of positive tests for the infectious diseases in the total and screened samples were markedly greater than current rates in the U.S. general population.

To identify patient factors related to positive tests, a subset of the medical charts was reviewed (N=128). Most participants in this subset were male (90 patients, or 70 percent), with a mean±SD age of 37.06±11.48 years and mean education level of 11.31±3.19 years. Fifty-eight patients (45 percent) were black, 51 (40 percent) were white, and 14 (11 percent) were Latino or Hispanic. Twenty-six patients (20 percent) were immigrants. Almost one third (40 patients, or 31 percent) were homeless, and only 24 (19 percent) had a primary care physician. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (44 patients, or 34 percent), followed by bipolar disorder (26 patients, or 20 percent); half of the participants (67 patients, or 52 percent) had some type of psychosis.

Logistic regression analyses were used to identify patient demographic and psychosocial risk factors for positive tests, except for HIV, which was excluded because of the small number of individuals with known serostatus.

Patients who screened positive on tuberculin skin tests tended to be older (odds ratio [OR]=3.96, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.70 to 9.25, p=.001), immigrants (OR=14.46, CI=2.17 to 96.53, p<.01), or homeless (OR=10.07, CI=1.83 to 55.44, p<.01).

Patients who screened positive for hepatitis A antibodies were also more likely to be older (OR=2.15, CI=1.12 to 4.11, p<.05) or immigrants (OR=19.41, CI=4.06 to 92.77, p<.001). Positive hepatitis B tests were associated with being an immigrant (OR=9.79, CI=2.29 to 41.85, p<.01) or having a history of drug use (OR=4.94, CI=1.35 to 18.04, p<.05). Patients who screened positive for hepatitis C antibodies were more likely to be older (OR=2.06, CI=1.06 to 4.00, p<.05) or to have a history of drug use (OR=11.24, CI=2.18 to 57.83, p<.01). Subsequent logistic regression analyses of substance type showed that cocaine and heroin use independently predicted positive screens for hepatitis B (OR=3.79, CI=1.21 to 11.83, p<.05 and OR=11.08, CI=2.25 to 54.50, p<.01, respectively) as well as hepatitis C (OR=3.32, CI=1.02 to 10.78, p<.05 and OR=9.95, CI=2.39 to 41.46, p<.01, respectively).

Discussion

This study provides the first estimate of hepatitis A antibody positivity and confirms the alarmingly high occurrence of positive tuberculin skin tests, hepatitis B and C, and HIV serologies in a state psychiatric hospital population. The frequency of positive tuberculin skin tests among patients screened (20.2 percent) was four times as great as that found in the U.S. general population and corroborates a previous report of 17 percent (

2,

7). Additionally, although the rate of hepatitis A in the studied population was similar to that in the general population, the frequencies of positive tests for hepatitis B and C among patients screened were five and 12 times as great as general population estimates, respectively (

8). Finally, considering that HIV tests were performed for less than 10 percent of admitted patients, the lowest possible rate of HIV would still be nine times that of the U.S. general population, assuming that patients who were not tested were HIV negative (

9). Overall, these estimates appear comparable to those reported in a study by Rosenberg and colleagues (

5), who observed a prevalence of 23.4 percent for hepatitis B, 19.6 percent for hepatitis C, and 3.1 percent for HIV in a large sample of individuals with severe mental illness.

Although older age and immigrant status were expected risk factors for positive tuberculin skin tests because of results from a previous study (

2), the study presented here is the first one that showed that these variables also predict positive screening for hepatitis A antibodies in a psychiatric population. Our data also confirm previous studies' findings that a history of drug use, in particular cocaine and heroine, increase the risk of screening positive for hepatitis B and C (

5,

6).

Several limitations of the study design are worth noting. First, because the data collection was retrospective, no control group was available. Consequently, we chose to examine general population estimates as a framework for evaluating the degree to which this population is at risk. Second, the reported rates of infection reflect data from screening tests for markers and antibodies rather than active or acute disease; some patients may have had illnesses in the past or even immunization, which may result in positive tests. Finally, the ORs for the risk factors may be somewhat questionable because of the smaller samples for the subset of charts reviewed. Yet, the significant predictors that we identified are similar to ones previously reported in the literature.

Conclusions

The study presented here underscores the value of screening for tuberculosis, hepatitis, and HIV among individuals with severe and persistent mental illness, especially because effective medical treatments are now available. Because of the high rate of hepatitis C in this sample, the ELMHC has implemented routine screening for the hepatitis C antibody among all patients admitted to the psychiatric unit since 2000. Patients found to be positive for hepatitis C antibodies receive counseling from a nurse, confirmatory laboratory testing, and referral to the internal medicine consultant for continued management. Although patients were not immunized in this setting, mental health institutions should consider initiating vaccinations upon admission to treatment, considering the risk of contracting hepatitis A and B in this and other psychiatric samples. In any case, standard infectious disease screens and follow-up procedures—such as those at ELMHC or the STIRR (screen, test, immunize, reduce risk, and refer) intervention proposed by Rosenberg and colleagues (

10)—should be developed, implemented, and tested to address this public health crisis that affects a particularly vulnerable patient population.