Increasingly, women are migrating to the United States from Latin America and leaving their children in their homeland in the care of family or friends. Women from Latin America seem to be migrating more frequently because of changes in the global economy, with the U.S. economy featuring fewer manufacturing jobs and increasingly more low-wage industrial and service-sector jobs than it had had in the past in which women are desirable employees (

1,

2). Although it is not possible to obtain accurate information about undocumented migrants who enter the United States, recent studies suggest that Latinas are now as likely as Latino men to immigrate to the United States (

3,

4). Families who migrate often do so in a "stepwise" fashion (

5). As women have become more employable in the United States, mothers come first and work for extended periods to gain resources to bring their children to join them.

Very little is known about the psychological impact of family separations arising out of immigration. Several clinical and ethnographic reports suggest that such separations result in negative effects on families at reunification (

6,

7,

8). However, data are not available to document how the likelihood of being separated from children may affect the mental health of immigrant mothers. We used a cross-sectional survey to gather data and hypothesized that mothers who leave their children as they immigrate to the United States would report higher rates of depression than immigrant women who do not experience such separations.

Methods

The data were obtained while screening prospective participants for the Women Entering Care (WE Care) study (

9). The study was reviewed and approved by three institutional review boards (Georgetown University, the State of Maryland, and the University of California, Los Angeles) with oversight responsibilities. All participants gave written informed consent for screening in either English or Spanish.

Women were screened in Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) programs that target low-income pregnant and postpartum women and their children (up to five years of age). Women were also screened in county-run Title X family planning clinics, funded by national grants for comprehensive family planning services for young and low-income women, and in pediatric clinics for low-income families. Women who were living in a subsidized-housing project or attending programs for county welfare recipients were screened as well.

Women were screened for major depression while they were at the service settings. Screenings were conducted from March 1997 to December 2001. Refusal rates for screening were very low.

Measures

All measures were obtained from personal interviews administered by WE Care project staff. Demographic information obtained in the interviews included age, marital status, education, housing status, employment status, country of birth, whether the women had children younger than 18 years, and living arrangements for their children.

To assess mental health problems, the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (Prime-MD) was used (

10). Women at high risk of major depressive disorders and significant somatic complaints were identified. The Prime-MD uses modified

DSM-IV-TR criteria (

11) and reports good agreement with independent psychiatric diagnoses. The Prime-MD is guided by a structured interview, with an overall accuracy rate of 88 percent (

10). The Spanish language Prime-MD was translated and back translated by a bilingual multicultural team and finalized with a Latino translation team that worked for the United Nations.

Data analyses

All data analyses were conducted with SAS (

12). Simple descriptive statistics were used to characterize the samples, and chi square tests and one-way analysis of variance were used to identify significant differences across the three groups of women. Logistic regression analyses (Proc Logistic in SAS) were conducted to predict depression diagnoses given demographic characteristics.

Rates of missing data were low (.1 to .6 percent) for all demographic characteristics. We first carried out analyses using all cases with complete data. To avoid discarding any information, we performed multiple imputation of missing data using an approximate Bayesian bootstrap method with hot-deck cells determined with predictive mean matching (

13). Variables with the fewest number of missing values were imputed first. Because complete-case and multiple-imputation results were nearly identical, only regression analyses with multiple imputed data are presented.

Results

WE Care sample

For the overall WE Care study we interviewed 16,286 women (11,151 in Prince Georges County, Maryland; 3,034 in Montgomery County, Maryland; and 2,101 in Arlington and Alexandria, Virginia) from March 1997 to May 2002. We screened 10,043 women who attended WIC services, 5,017 who attended family planning services, 1,144 who brought children to pediatric services for low-income families, and 82 who lived in subsidized-housing projects or who attended programs for county welfare recipients. Of the total screened, 5,342 were Latina; 5,122 were Latina immigrants. Most of the Latinas were from Central America: 3,683 were Central Americans (71.9 percent), 2,095 were El Salvadorian (40.9 percent), 692 were Nicaraguan (13.5 percent), 481 were Guatemalan (9.4 percent), 287 were Mexican American (5.6 percent), and 128 were from Belize, Costa Rica, or Honduras (2.5 percent). A total of 1,291 were South American (25.2 percent), and 148 (2.9 percent) were from the Caribbean

Latina participants

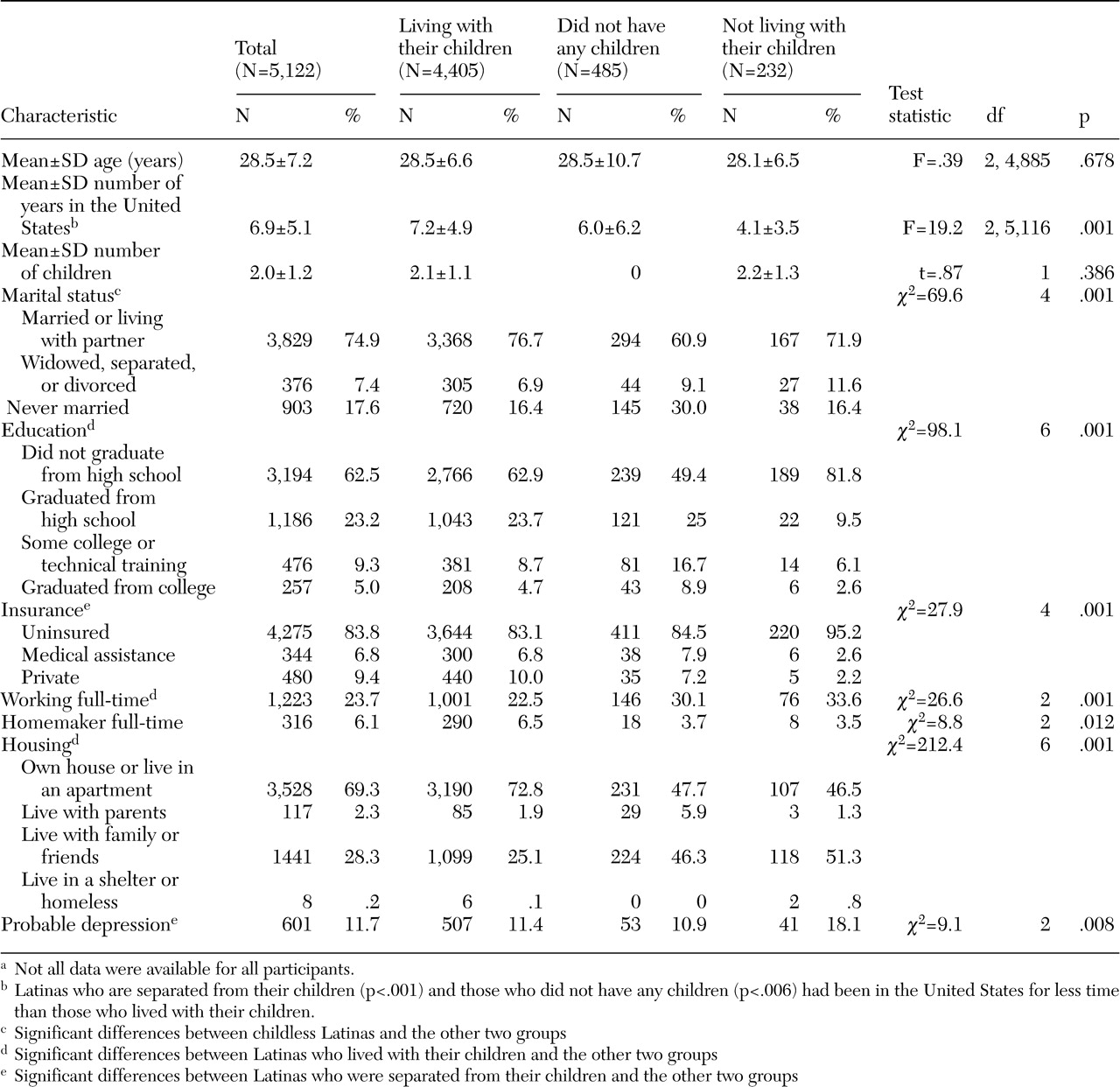

The immigrant Latinas in this study are described in

Table 1. Three groups of women were compared: Latinas who lived with their children, those who did not have children, and those who were separated from their children. Among Latinas who were screened and reported information about their children, 4,405 (86.0 percent) had all their children younger than 18 years living with them, 485 (9.5 percent) did not have any children, and 232 (4.5 percent) reported that they had children younger than 18 years who were living with relatives in another country.

As shown in

Table 1, the women were generally young and had nearly seven years of residence in the United States. The three groups of women differed in the number of years they had lived in the United States; Latinas who were living with their children reported living in the United States for a longer time than the other two groups. The women also differed in their likelihood of being married; childless women were less likely than those in the other two groups to be married or living with their partner. The Latina immigrants also differed in levels of education; those who lived with their children reported higher levels of education than those in the other two groups. The three groups also differed in the likelihood of being insured; Latinas separated from their children were more likely than those in the other two groups to be uninsured. The groups also differed in work status; Latinas who lived with their children were less likely than those in the other two groups to work full-time. The three groups also differed in living arrangements; immigrant mothers who lived with their children were more likely to live in their own home or apartment, and childless women and women separated from their children were more likely to live with family or friends. The rates of depression were 11.4 percent for women who lived with their children, 10.9 percent for those who did not have children, and 18.1 for those who were not living with their children.

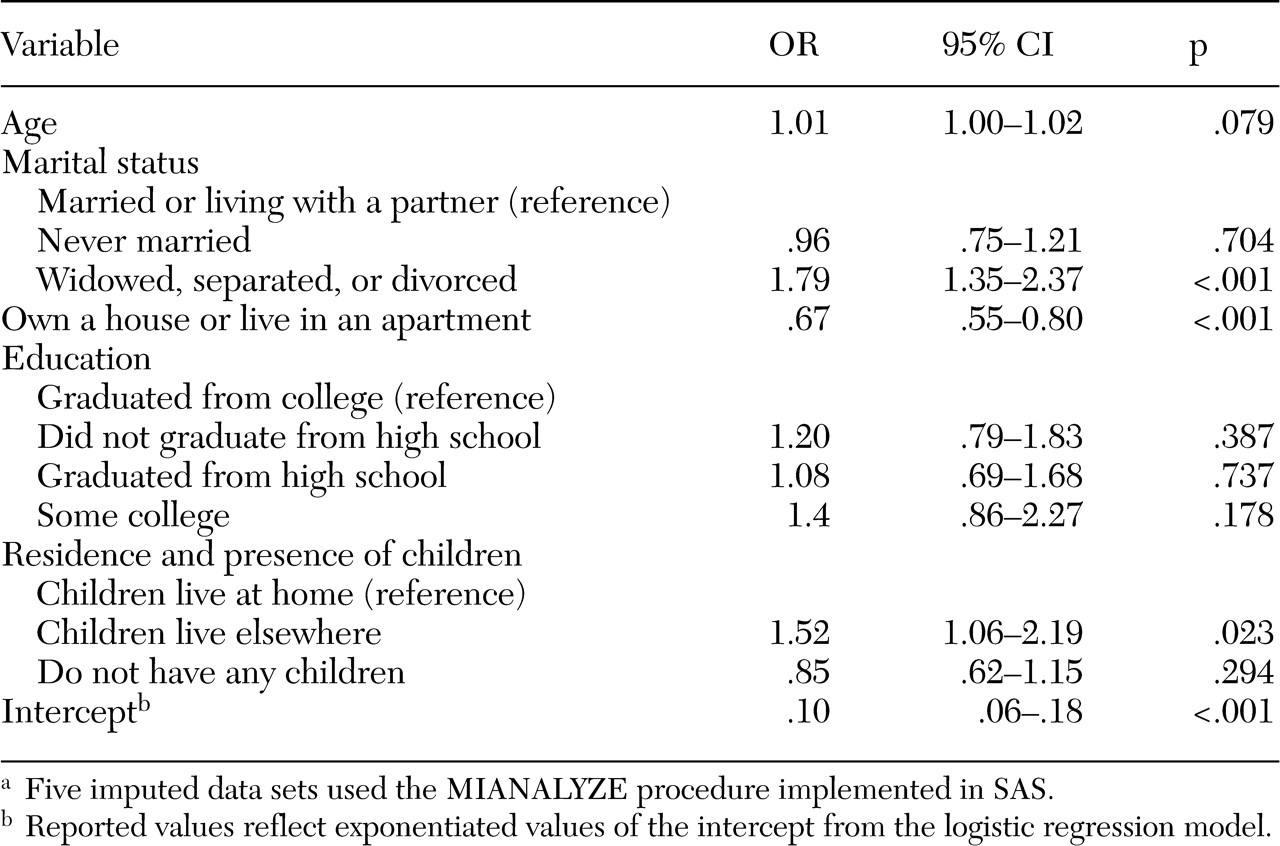

Rates of depression

To determine whether the three groups of immigrant Latinas differed in terms of depression, logistic regression analyses were conducted, which controlled for age, marital status, education, and housing status. Results are reported in

Table 2. Being widowed, separated, or divorced and being separated from one's children were significant predictors of depression. This analysis showed that having children who lived elsewhere predicted the likelihood of major depression even after demographic differences were controlled for among the samples. Specifically, the odds of having depression among women who were separated from their children were 1.52 times as great as the odds for women with children who lived at home. Women who did not have children were no more likely to be depressed than those who lived with their children.

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first empirical study of which we are aware that documents the mental health status of immigrant Latinas separated from their children. In this study we examined the likelihood of major depression among immigrant women from Latin America who were living in the United States. We found that even after demographic differences were controlled for, the odds of depression among immigrant Latinas who were separated from their children was 1.52 times as great as the odds for those whose children were currently living with them.

This study has important clinical implications. Health care clinicians who treat young immigrant women should be alert to signs of depression among those who have left children with relatives in their homelands. The sadness many of these women feel about leaving their children may make them particularly vulnerable to major depression.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, all measures are based on self-reports. Second, our measure of major depressive disorder may be less reliable than a complete diagnostic interview. Third, the data analysis was correlational and the study design was observational. No causal inference can be made about the impact of separation from children on mental health. Although we documented that immigrant Latinas whose children remained in their homeland reported higher rates of depression than those who lived with their children and those who did not have children, we cannot say that the separation from children caused the higher rates of depression. Despite these limitations, this study provides the first data that suggest mental health consequences of familial separation during immigration. This study suggests that immigrant women who are separated from their children should be screened for depression and treated for this disorder as need arises.

Acknowledgments

Data were collected and analyzed through funding from grant 5-R01-MH-56864-5 from the National Institute of Health, grant 5-SP01-MH-59876-02 (Latino Research Program Project) from the National Institute of Mental Health, and from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Dr. Miranda's time writing this article was funded through three centers: Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research's Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly, which is funded by grant 3-P0-3A-G021-684 from the National Institute on Aging; grant 1-P20-MD-00148-01 from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities; and grant MH-068639-01 from the Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care.