It is hazardous to infer bias solely from the existence of disparities in diagnosis and treatment (

18). However, this inference has been made repeatedly, largely on the basis of the cross-classification of race and the diagnosis of psychotic and mood disorders (

19). Furthermore, the word "bias" assumes that, given the same set of symptoms, clinicians will assign an African-American patient a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and a white patient a diagnosis of an affective disorder. The issue of accurate diagnosis and treatment of depression is even more critical among elderly patients, for whom depression management is more complex because of the co-occurrence of medical illnesses and neuropsychiatric disorders. The potential mismanagement of a mood disorder that has been misdiagnosed as a psychotic disorder in an elderly patient from a racial minority group could lead to poor outcomes and side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia.

Results

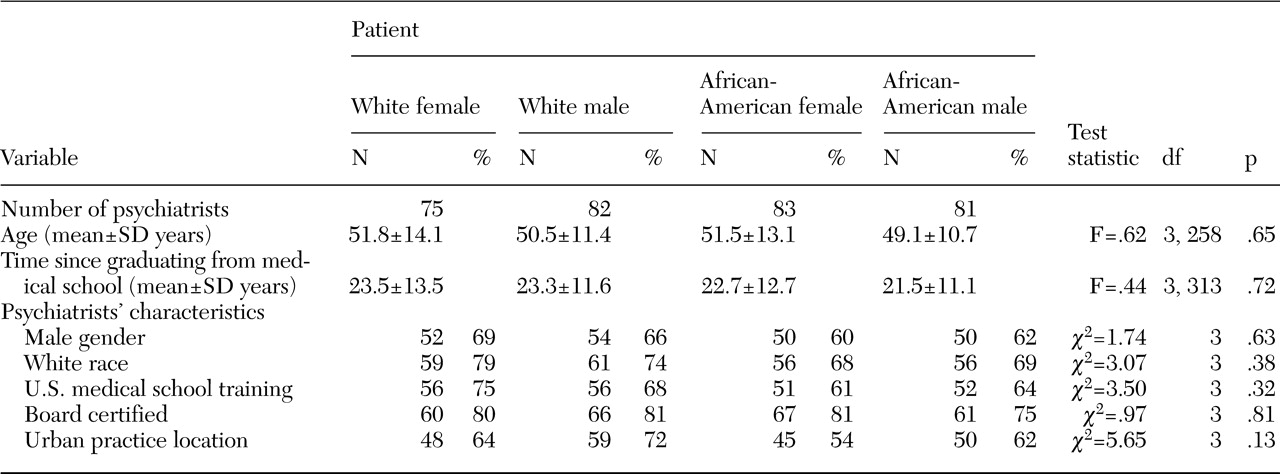

A total of 329 psychiatrists volunteered to participate in the study. Eight psychiatrists dropped out before viewing their assigned vignette. The remaining psychiatrists (N=321) who were randomly assigned to each vignette group did not differ significantly on any characteristic examined (

Table 1).

Primary diagnosis

A total of 260 psychiatrists (81 percent) assigned a diagnosis of major depression to the patient in the vignette. Analysis of the sample by vignette group showed no significant differences in the percentages of psychiatrists who diagnosed major depression: 73 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 83 percent (68 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 80 percent (66 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 88 percent (71 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Assigned diagnoses other than depression included dementia, alcohol abuse, delusional disorder, and schizoaffective disorder.

Level of certainty in diagnosis

Among the psychiatrists who assigned a diagnosis of major depression, there were no significant differences in mean level of certainty in the diagnosis (rated as zero to 100 percent) by vignette: 65±17.68 percent for the white female vignette, 65±19.94 percent for the white male vignette, 66±20.08 percent for the African-American female vignette, and 64±19.03 percent for the African-American male vignette.

Management recommendations

A majority of the psychiatrists chose an antidepressant as their first-line treatment; this choice was consistent across vignettes: 77 percent (58 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 78 percent (64 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 75 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 77 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. A majority of the psychiatrists chose newer antidepressant agents, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as their first-line treatment, and this choice did not differ significantly by vignette: 73 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 76 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 75 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 77 percent (62 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. For the sample overall, psychiatrists who assigned a diagnosis of major depression were significantly more likely to choose a newer antidepressant (229 psychiatrists, or 88 percent) compared with those who assigned other diagnoses (12 psychiatrists, or 20 percent) (χ2=123.56, df=1, p<.001).

A majority of the psychiatrists recommended long-term follow-up (more than six months), and this did not differ significantly by vignette: 67 percent (50 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 79 percent (65 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 67 percent (55 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 73 percent (59 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Psychiatrists also consistently indicated that the single piece of additional information desired was a full medical history with laboratory work: 49 percent (37 psychiatrists) for the white female vignette, 51 percent (42 psychiatrists) for the white male vignette, 57 percent (47 psychiatrists) for the African-American female vignette, and 53 percent (43 psychiatrists) for the African-American male vignette. Other additional information chosen by participants included head CT, full substance abuse history, and Mini-Mental State Examination.

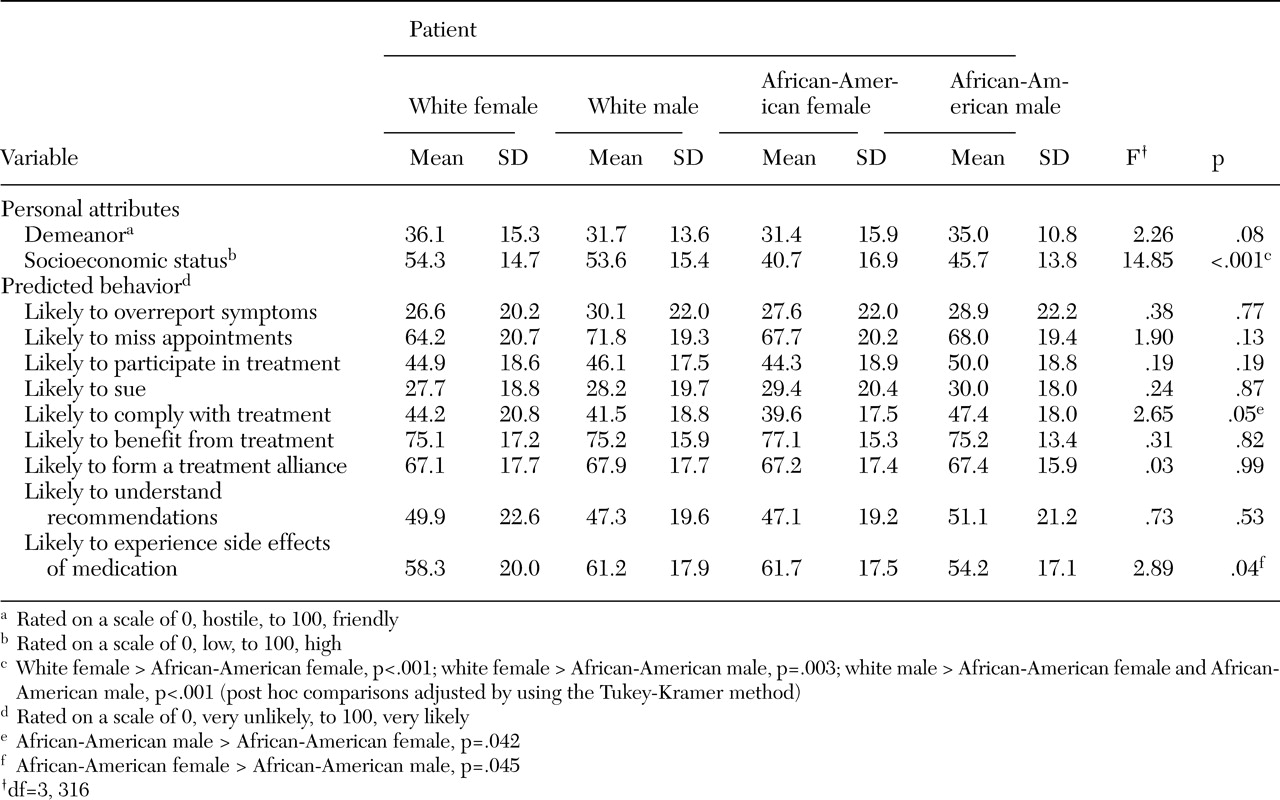

Psychiatrists' assessment of patient characteristics

The psychiatrists were asked to assess two personal attributes of the patient—demeanor and socioeconomic status—as well as nine predicted patient behaviors. The psychiatrists' assessments did not differ significantly by patients' race or gender (

Table 2), with the exceptions of the psychiatrists' estimates of the patient's socioeconomic status, adherence to treatment, and likelihood of experiencing side effects of medication. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the patients portrayed in both the white male and the white female vignettes were rated as being of significantly higher socioeconomic status than those portrayed in the African-American male and African-American female vignettes (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05). The African-American female patient was rated as less likely to adhere to treatment (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05) and more likely to experience side effects of medication (Tukey-Kramer test, p<.05) than the African-American male patient.

Psychiatrists' estimates of socioeconomic status were not associated with their choice of diagnosis or estimate of patient attributes, except for demeanor. A significant relationship was found between rating of socioeconomic status and estimates of patient demeanor (lower socioeconomic status associated with a more hostile demeanor) (F=5.09, df=1, 312, p<.03); estimate of patient demeanor also appeared to account for some of the variation in the estimate of socioeconomic status among the vignettes (F=3.05, df=3, 312, p<.03).

Analyses using psychiatrist characteristics

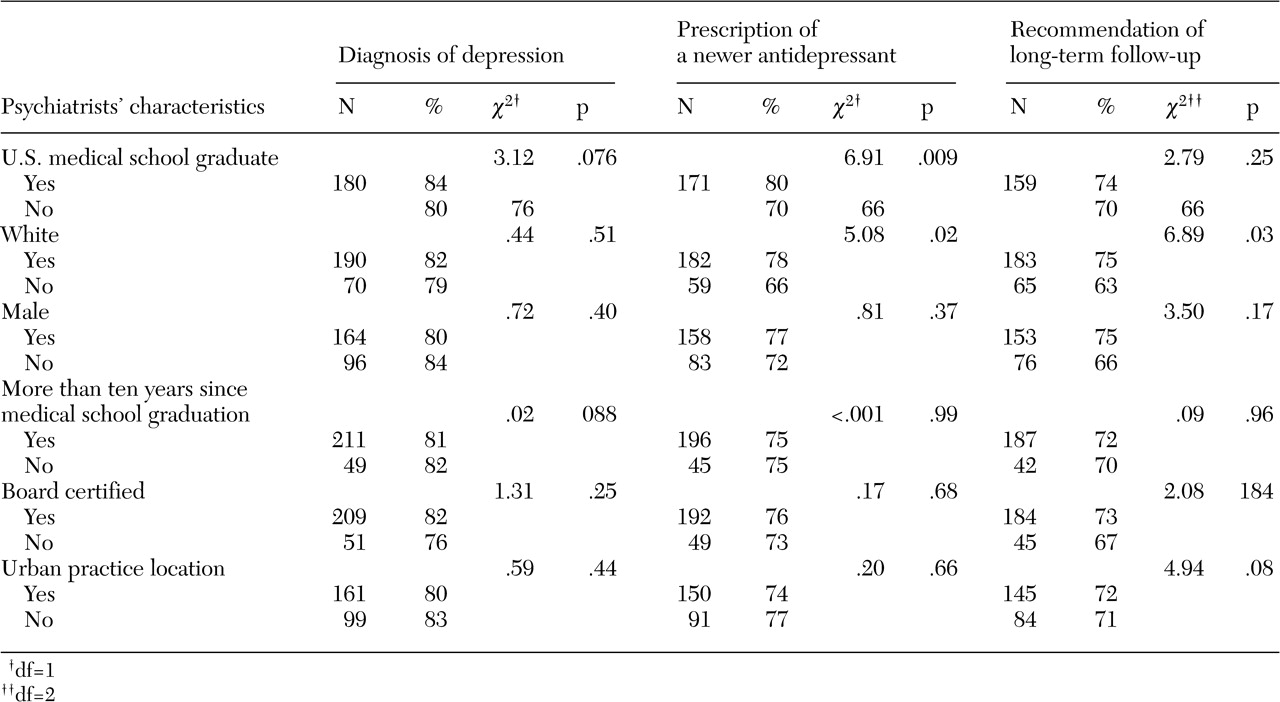

Diagnosis, treatment, and management recommendations for all patients, by psychiatrist characteristics, are presented in

Table 3. Notably, the location of the medical school at which the psychiatrists received their training (United States versus an international medical school) and psychiatrists' race were each associated with psychiatrists' diagnosis and management recommendations. Overall, 67 percent of the total sample (215 psychiatrists) were graduates of U.S. medical schools, and 33 percent (106 psychiatrists) were graduates of international medical schools. The overall racial breakdown of the psychiatrists was 72 percent white (232 psychiatrists), 19 percent Asian (60 psychiatrists), 5 percent other (15 psychiatrists), 2 percent African American (seven psychiatrists), and 2 percent Hispanic (seven psychiatrists). For graduates of international medical schools, the racial breakdown was 49 percent Asian (52 psychiatrists), 35 percent white (37 psychiatrists), 8 percent other (eight psychiatrists), 5 percent Hispanic (five psychiatrists), and 4 percent African American (four psychiatrists).

Graduates of international medical schools were less likely to diagnose depression and significantly less likely to choose a newer antidepressant as a first-line treatment than graduates of U.S. medical schools. Compared with white psychiatrists, psychiatrists of other races were significantly less likely to choose a newer antidepressant as a first-line treatment and to recommend long-term follow-up. Psychiatrists' gender, board certification status, time since graduation, and practice location were not associated with diagnosis or with management recommendations.

In terms of assessment of patients' characteristics, graduates of international medical schools were significantly more likely than U.S. graduates to indicate that the patients portrayed in three of the four vignettes were overreporting symptoms (white male, t=-2.64, df=80, p<.01; African-American female, t=-3.62, df=80, p<.001; and African-American male, t=-3.12, df=79, p<.003). Significantly more international graduates rated the African-American female as being more likely to sue for malpractice (t=-2.04, df=80, p<.05) and the African-American male as being less likely to understand the psychiatrist's recommendations (t=2.00, df=79, p<.05). Finally, compared with graduates of international medical schools, U.S. medical school graduates were more likely to predict that the white female patient would experience side effects of medication (t=2.26, df=73, p<.03).

Compared with white psychiatrists, psychiatrists of other races were more inclined to indicate that the white male patient was overreporting symptoms (t=-3.07, df=80, p<.004) and was more likely to sue for malpractice (t=-2.67, df=80, p<.01). Psychiatrists of other races also rated the African-American female patient as being of lower socioeconomic status (t=2.41, df=80, p<.02).

Post hoc analyses of psychiatrists' characteristics

Separate logistic regression models were computed for each psychiatrist trait, with patients' race and gender included as predictor variables. The results for diagnosis indicated that the effect of patients' gender was significant across all models, except for number of years in practice—male patients were 1.8 times as likely to receive a diagnosis of depression as female patients (95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.03 to 3.26). The interaction between patients' gender and race was examined and was found to be nonsignificant.

Psychiatrists' race as well as the location of the medical school at which they were trained were significantly associated with choice of newer antidepressants (p<.05). Psychiatrists' race and medical school location were highly correlated (Spearman rank-order correlation coefficient [rs]=.59, p<.001); 84 percent of the white psychiatrists (196 of 232) had been trained in the United States, whereas only 22 percent of the other psychiatrists (20 of 89) had been trained in the United States (χ2=112, df=1, p<.001). Neither patients' race nor patients' gender was predictive of treatment choice in any of the models.

Discussion and conclusions

Although clinician bias is often cited as a possible explanation for racial disparities in the diagnosis of depression, psychiatrists' contribution to the disparities had not been directly examined before our study. Misdiagnosis among older African-American patients was suggested by two case series (

16,

17). However, it is not clear from these case series whether the misdiagnosis was racially based or was due to nonracially based misdiagnosis that may have been more prevalent before the

DSM-III era. Our findings suggest that psychiatrist bias based simply on the color of a patient's skin (as well as other characteristics associated with race, such as facial features and speech style) does not explain the lower rates of diagnosis of clinical depression among African-American patients.

In clinical settings, the diagnosis and treatment of depression may be affected by other patient-level factors, including variations in presentation of symptoms of depression, lower use of formal mental health care settings for treatment among elderly African Americans, and patients' treatment preferences. The first factor is suggested by previous findings that mixed-age African-American patients with depression had higher ratings of hostility and irritability and a greater frequency of somatic complaints (

1,

23,

24). The second factor may be indicated by studies demonstrating different patterns of help seeking and service use for depression among African Americans, including lower use of mental health specialists (

25) and more reliance on informal support (for example, friends or ministers) for emotional problems (

26,

27). Furthermore, elderly patients, men, and African Americans are more likely to see primary care physicians than psychiatrists for mental health treatment (

28). It is possible that there are greater disparities in mental health care among primary care patients than among patients who are seen by psychiatrists.

The third factor is supported by a recent finding that primary care providers recognized depression and recommended treatment for African-American patients as often as for white patients, but African-American patients were significantly less likely to accept antidepressant medications (

29). Previous studies that showed lower rates of diagnosis and treatment of clinical depression among elderly African Americans may have been affected by variations in symptom presentations, selection bias in examining samples of patients who presented for treatment, and the effects of patients' treatment preferences. A strength of our study was the fact that patients' presentations were standardized to enable us to isolate and examine psychiatrists' decision making. Given our results as well as those of these other studies, we suggest that racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders are likely the result of a complex interplay of patient and provider factors and cannot be merely ascribed to "misdiagnosis."

Regarding the findings on psychiatrists' estimates of patients' socioeconomic status and of race and diagnosis, it is possible that psychiatrists based their estimates of socioeconomic status on known population differences in income as opposed to racial bias. Alternatively, it is possible that, even if psychiatrists' estimates of socioeconomic status were influenced by racial bias, this bias did not affect the psychiatrists' choices of diagnosis.

Although patients' race and gender had a limited effect on psychiatrists' decision making and estimate of patients' characteristics, certain characteristics of the psychiatrists themselves—notably, whether they attended a U.S. medical school or an international medical school—did have an impact. Psychiatrists who graduated from international medical schools, most of whom were Asian, were less likely to diagnose depression or to recommend newer antidepressants as initial treatment and more likely to predict negative behaviors, such as nonadherence to medications, for both white and African-American patients. These findings may reflect cultural differences within the psychiatrist-patient dyad. Graduates of international medical schools frequently work in the public sector, where they encounter patients from racial minority groups and spend, on average, 35 percent more time working with elderly patients than do graduates of U.S. medical schools (

30). Thus these results are of practical concern and may suggest the need for targeted educational initiatives for cultural and aging competency for psychiatrists who are graduates of international medical schools.

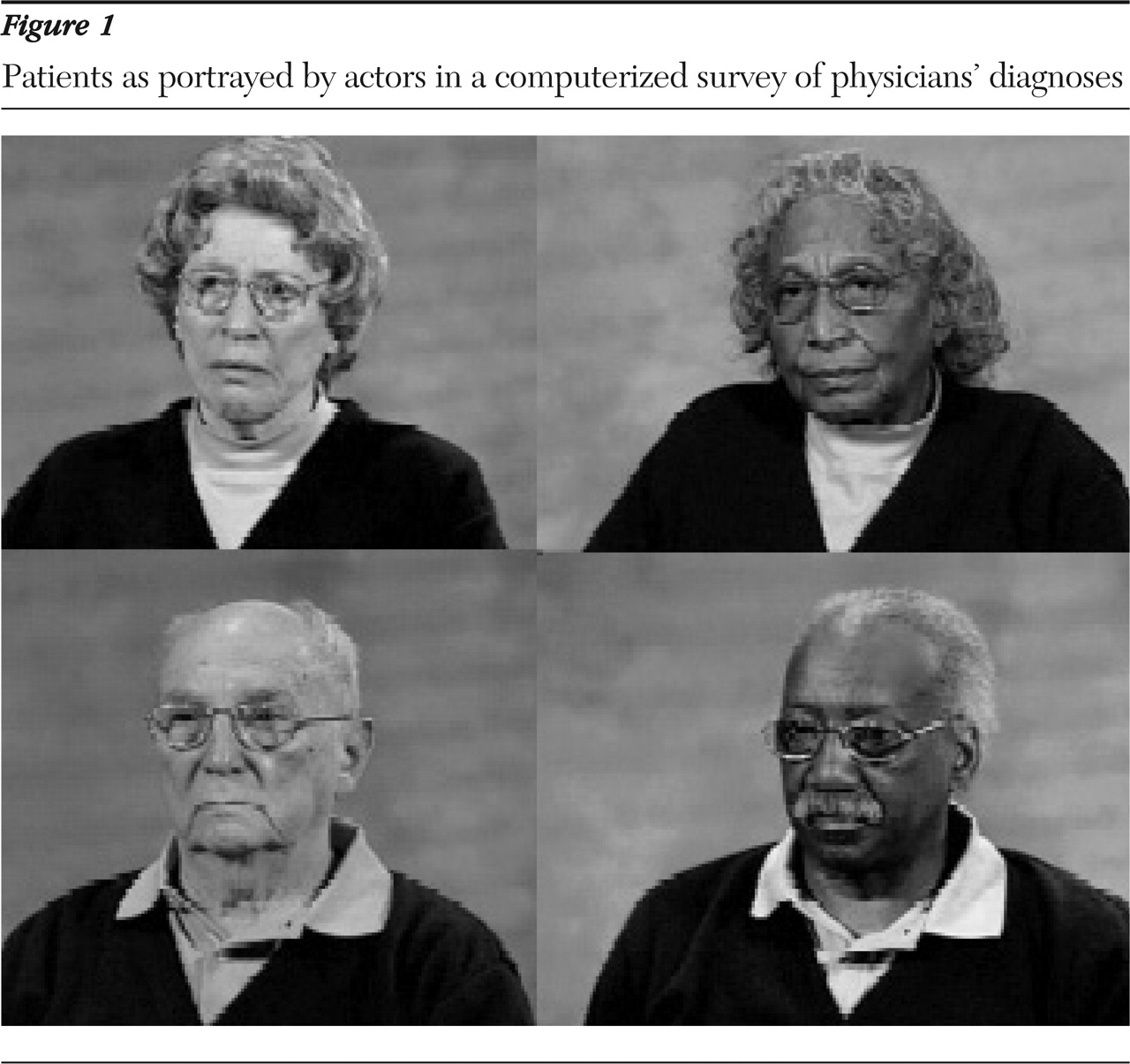

Our study had several limitations. First, we used videotaped vignettes of actors portraying patients. Although we meticulously standardized and piloted the vignettes, subtle differences between actors' appearances or nonverbal communication might have affected our results. The use of case vignettes to assess clinical decision making is supported by several studies (

31,

32,

33,

34); videotaped (rather than written) vignettes may enhance the accuracy of physicians' decisions (

34). Such techniques also permit a degree of control that is unattainable in observational studies, allowing determination of the influence of nonmedical factors on physicians' decision making (

35). However, it is not known whether our survey instrument correlates with actual psychiatrists' decision making.

It is also possible that the study participants' knowledge of the previous study by Schulman and colleagues (

21) that had been the subject of wide discussion affected our results. However, we requested that study personnel note any mention of or questions about that study by the participants in our study; no participant mentioned this previous study. It is likely that, given the elapsed time between the publication of the Schulman study and the implementation of our study (three years), the different setting and focus of the meeting at which study participants were recruited (cardiology versus psychiatry), and the fact that each participant viewed only one vignette (and in many cases thought this was the only vignette), most participants did not make a connection between the Schulman study and our own.

In addition, the fact that we recruited psychiatrists at a national meeting may have resulted in a nonrepresentative sample. Psychiatrists who attend such meetings and who volunteer to participate in a study such as ours may be more attuned to the culturally sensitive diagnosis of depression. Finally, to enable us to focus on the relationship between patients' race and psychiatrists' decision making, other patient-related factors (such as socioeconomic status or educational level) were not assessed. However, clearly these factors may have an impact on physicians' decision making.

These limitations notwithstanding, the results of this study provide new data on the contribution of psychiatrists to racial differences in the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression. It has been suggested that racial disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders are related to inferior treatment provided by white professionals (

36) and that schizophrenia among black patients is systematically overdiagnosed whereas affective disorders are systematically underdiagnosed among black patients (

37). However, until the elements of the treatment process (provider-related variables and patient-related variables) are broken down and examined, these assumptions about causality are merely conjecture.

Our findings suggest that, given standardized symptom pictures, psychiatrists are no less likely to diagnose depression among African-American elderly patients than among other patients and do not show evidence of bias based simply on race. Differences in rates of diagnosis and treatment of clinical depression that were found in previous studies may instead reflect the complex interplay between provider factors and patient-related factors, such as variations in the use of health care services, alternative presentations of symptoms, and patients' preferences. The impact of psychiatrists' having trained at international medical schools on diagnosis, treatment choice, and ratings of patients' attributes may suggest a need for targeted cultural and aging competency initiatives for such psychiatrists, many of whom provide important and much-needed care in the public sector to elderly patients from racial minority groups.