Severe mental disorders take a toll on the body, but specific health risks change over time, reflecting changes in living conditions and treatment practices. For example, institutional care led to increased mortality from tuberculosis, but cigarette consumption among patients in asylums was sometimes restricted (

1). Individuals in contemporary community-based care do not suffer from the infections common in institutions, but they experience health risks associated with new living conditions (

2,

3), and they smoke at extremely high rates (

4). Inactivity and poor nutritional options contribute to a range of obesity-related problems (

5). High rates of alcohol and drug abuse have long-term health implications even for those who have achieved sobriety (

6). Current and former users of intravenous drugs and crack cocaine have elevated risks of HIV-AIDS and hepatitis C (

7,

8,

9), which change risk profiles dramatically from those of older cohorts.

Psychiatric illness and treatment compound these problems. Depressive symptoms clearly increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes (

10,

11). Schizophrenia syndromes may predispose persons to metabolic syndrome (hypertension, hypercholesteremia, insulin resistance, and abdominal adiposity), which is more generally attributed to neuroleptic treatment (

12,

13,

14). Selected agents within virtually all classes of psychotropic medications contribute to weight gain (

15), and some second-generation neuroleptics are associated with still more obesity and metabolic dysfunction (

16,

17). These agents have most affected the treatment of schizophrenia, but their increasing use for mood disorders heralds effects on a broader diagnostic spectrum (

18,

19).

Morbidity studies document the impact of behavioral and treatment-related factors, showing consistently elevated rates of cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disorders, diabetes, and liver disease. Himmelhoch and colleagues (

20), using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, found a 22.6 percent prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults with severe mental illness compared with a reported rate of 6 percent in the general population. Using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Daumit and colleagues (

21) found that obesity, smoking, and diabetes were reported twice as frequently among persons with severe mental illness. In a retrospective cohort study of 3,022 persons with schizophrenia, Curkendall and associates (

22) described adjusted relative risks of 2.2 for cardiovascular disease and 1.8 for diabetes.

Dickey and colleagues (

23) used statewide Medicaid data in Massachusetts to examine treated prevalence rates for eight common disorders among Medicaid recipients with nonaffective psychoses who were in the disabled benefit category and recipients with no mental illness who were in the Aid to Families With Dependent Children benefit category. Rates for all eight disorders—diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, asthma, gastrointestinal disorders, skin infections, malignant neoplasms, and acute respiratory disorders—were higher among those with mental illness. In a previous study we found that substance abuse increased rates of treatment for specific disorders but did not fully account for excess morbidity among 781 persons with mental illness (

24).

Medical disorders reduce life expectancy among persons with mental illness. High rates of suicide and accidental deaths sometimes obscure medical mortality in this population; however, an international literature confirms the high mortality rates attributable to medical disorders, especially cardiovascular disorders, respiratory illness, and diabetes (

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30). This excess mortality is generally expressed as a ratio between rates observed among persons with severe mental illness and rates expected for persons with no mental illness who are of the same age and gender. Thus elevated ratios do not indicate different causes of death than those for the general population but rather earlier deaths from similar causes.

Although medical morbidity and mortality are well documented, less attention has focused on the functional impact of medical morbidity. Individuals with physical disabilities often have problems performing activities that are necessary for independent living, such as shopping or housekeeping. However, these abilities are not systematically assessed among adults with psychiatric diagnoses—at least until they enter services designed for elderly persons with mental illness. In view of the early mortality from chronic medical disorders among adults with severe mental illness, we suspected that they might experience early onset of physical limitations associated with chronic medical illness. To examine this phenomenon, this study looked at a sample of community-based adults with severe mental illness in order to examine demographic and clinical determinants of physical functioning and to compare them with national age and gender-matched norms.

Methods

Sample and setting

The sample for this cross-sectional study included 309 adults with severe mental illness who were recruited from July 2001 to December 2002 for a randomized trial and assessed at baseline. Persons were recruited for the study in four crisis residential programs operated by the San Francisco Progress Foundation (

31). These home-like settings provide short-term treatment to persons referred from inpatient or crisis services in the city and county of San Francisco. Clients in these programs are drawn from a citywide population and approximate a treated community sample, or those receiving acute and subacute services, of adults with severe mental illness (

24). Non-English speakers were excluded, as were persons with cognitive impairments that precluded participation in interviews and persons with no diagnosis except adjustment disorder. The clinical trial tested the benefits of adding an active health promotion intervention to basic primary care services for this population. The study and informed consent procedures were approved by the committee on human research of the University of California, San Francisco.

Data collection

Data were obtained by a structured face-to-face interview conducted at enrollment. Demographic data were recorded, and two questions about health care were asked: Do you see a regular doctor or nurse practitioner for health care? Do you go to a regular place for health care? Data on drug and alcohol use, including smoking, were obtained by use of the relevant section of the Addiction Severity Index (

32). Admitting diagnoses were extracted from clinical records.

Health status was measured by using the Medical Outcomes Health Survey Short Form 36 (SF-36). This self-report measure of physical and emotional well-being has been used widely in health outcomes studies (

33). Eight scales contribute to summary measures for physical and emotional health status. The instrument has been tested extensively for reliability and validity and normed for men and women in the general population (

33). The SF-36 has been employed successfully in studies of people with schizophrenia (

34,

35,

36), bipolar disorder (

37,

38,

39), and major depressive disorder (

40,

41,

42). It has been used in more than 300 studies of mental disorders, although the vast majority of such studies focus on depressive symptoms within the context of a medical illness. The key variable of interest for this research, physical functioning, was measured with the physical functioning scale of the SF-36, with scores standardized from 0 to 100 (

33).

A number of sources question the independence of physical and mental summary scores on this instrument, because both are affected by mood (

43), and because individual scales may contribute to both summary measures (

44,

45), and because of the general conceptual problems inherent in separating physical and emotional well-being (

44). However, the physical functioning scale consists of items eliciting concrete responses about physical limitations due to health, such as in carrying groceries, using stairs, bending, and lifting. This scale has the least association with emotional functioning of all eight SF-36 scales (

33,

46). For this reason we selected it as the best option for a generic measure of physical health status, independent of specific medical diagnoses.

Analysis

The sample was described by using means, medians (age, education, measures of health status, and physical functioning), and proportions (marital status, ethnicity, living situation, and income sources) for the total group by gender. Health-related characteristics were described by categories of admission diagnoses (schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychoses, bipolar disorder, depression, and others). We then examined several variables that we thought might be associated with physical functioning: gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, living situation in the past six months, recent employment (yes or no), and income (earned income, Social Security benefits, and family or other support). We also examined physical functioning in relation to lifetime substance use (number of years of use of alcohol to intoxication, opiates, stimulants, and smoking) and the number of drugs administered intravenously.

Associations between physical functioning and these variables were examined with Pearson correlations for continuous variables and with one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for categorical variables. Variables that had significant bivariate associations (p<.05) with physical functioning were selected as predictors for hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Our strategy for these analyses was to enter the set of sociodemographic predictors first, then the predictors related to substance use, and finally psychiatric diagnosis (dummy coded). Because current living situation was coded in five categories, dummy variables to represent the different living situations were entered as a group after entering the dichotomous sociodemographic predictors at step 1 but before entering the substance use predictors.

To compare the scores of study participants with national norms, we computed new physical functioning scores for the participants as deviations from the relevant norm group means. Normative means were available for women and men across approximate tenyear age intervals (

33). The deviation scores were tested against zero with a one-way ANOVA. We also tested for differences on these deviation scores among the age groups by using the Brown-Forsythe F*test as a guard against unequal variances among the groups and skewness in the distributions (

47).

Results

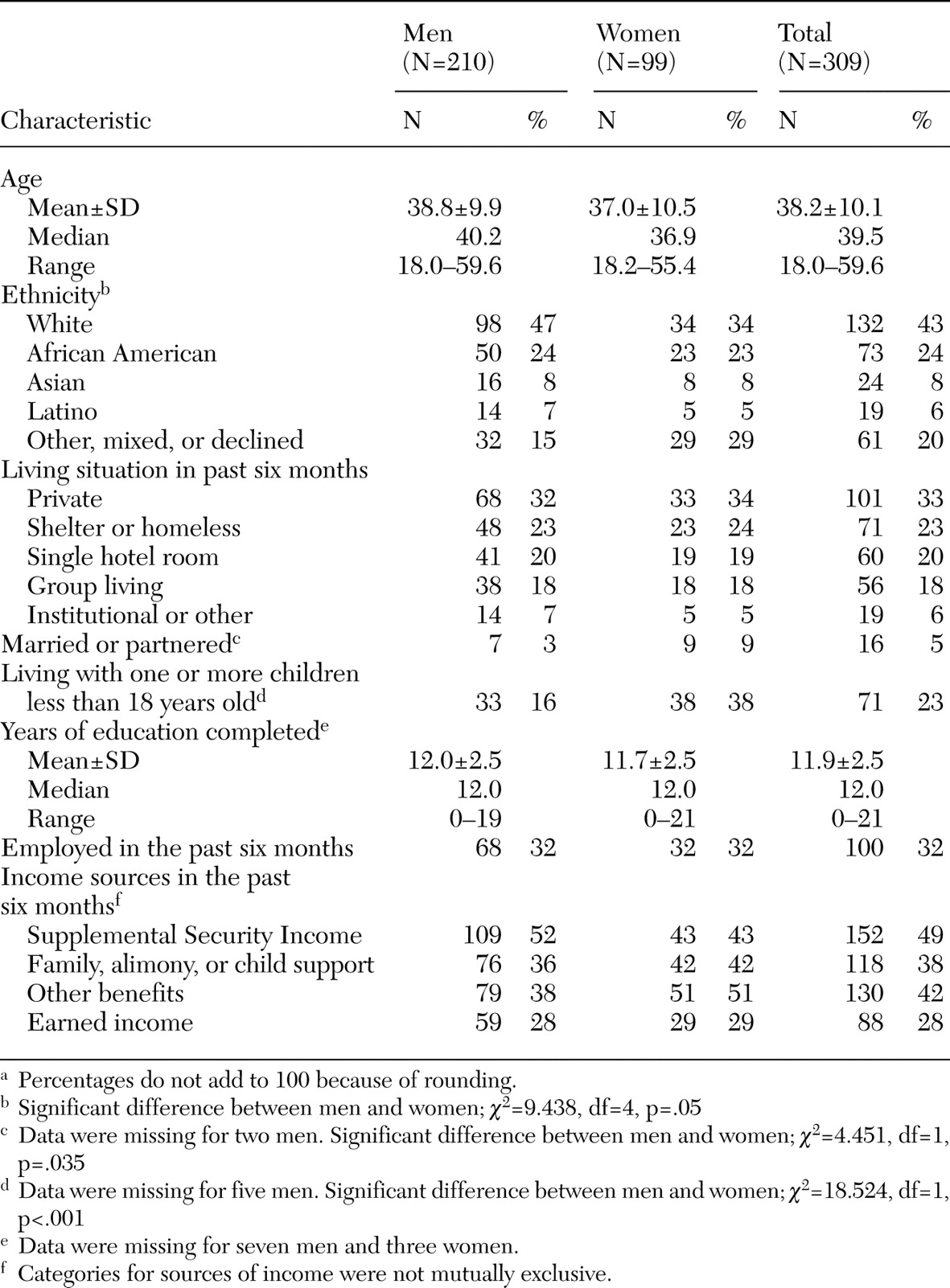

The sample included 309 adults, ranging in age from 18 to 60 (mean age, 38.2). Gender was self-reported, and the sample included 210 men, 91 women, and eight trans-gender persons, all of whom were male-to-female and considered as female in the analyses. Sociodemographic characteristics by gender are presented in

Table 1.

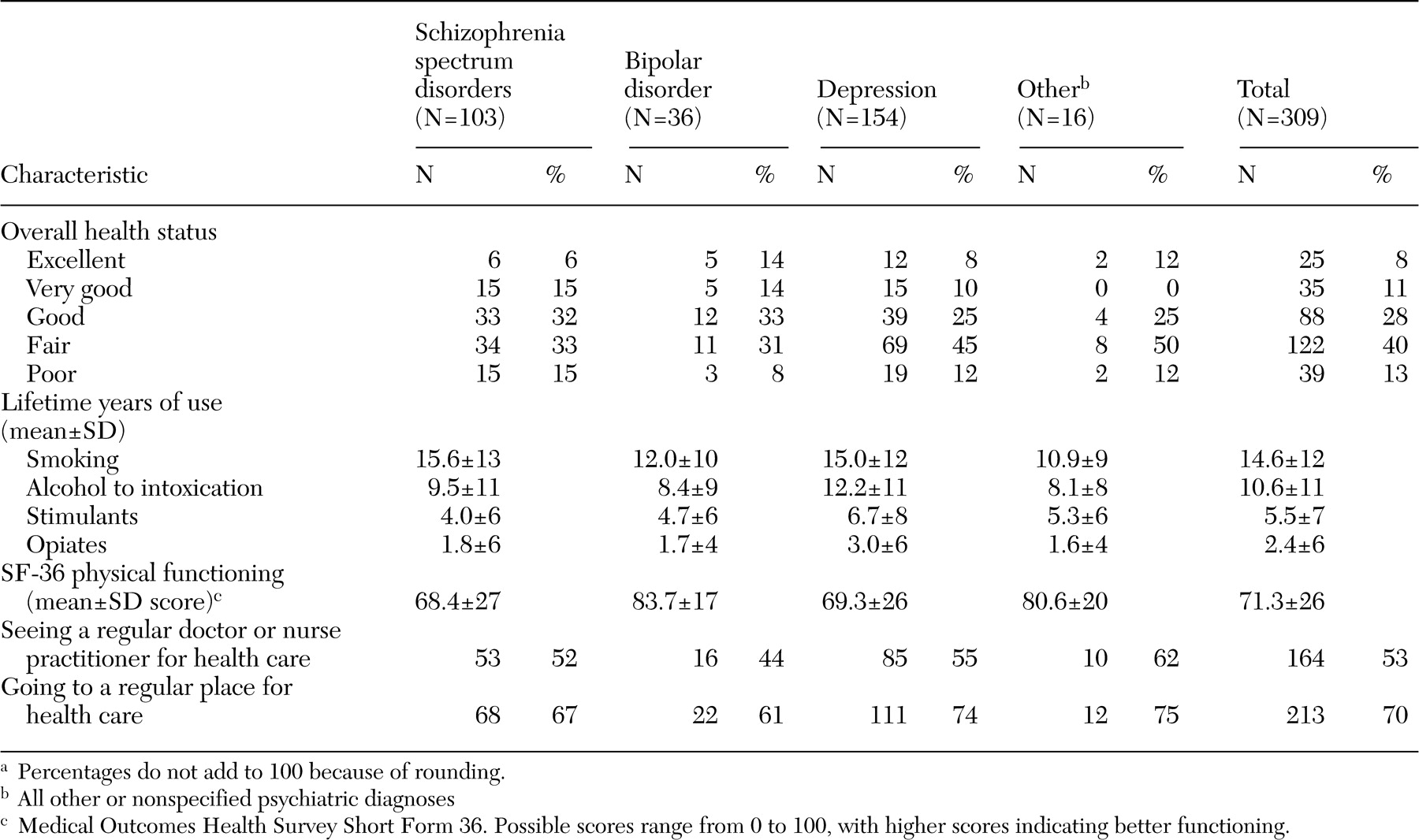

Table 2 reports health-related characteristics of the sample by admission diagnosis.

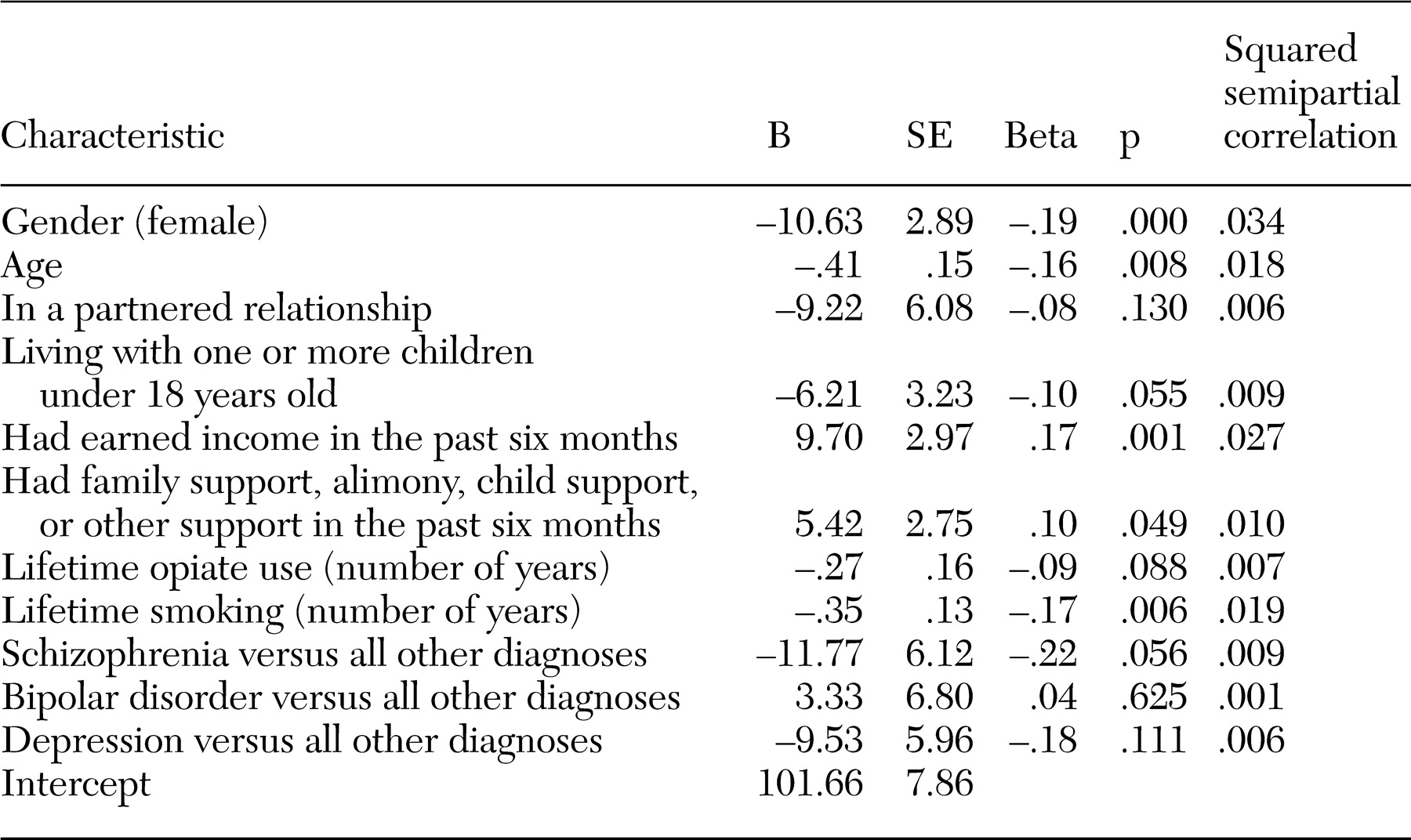

Results of the hierarchical regression analyses (

Table 3) showed that six sociodemographic variables (gender, age, being in a partnered relationship, living with at least one child under 18 years of age, having earned income in the past six months, and having family support, alimony, child support, or other support in the past six months) predicted 20 percent of the variance in physical functioning when entered into the model at the first step. Years of lifetime opiate use and smoking increased R

2 by 4 percent at the second step. Finally, psychiatric diagnosis at admission increased R

2 by 3 percent at the third step. The final model R

2 was .27 (F=9.92, df=11, 290, p<.001). Five predictors contributed significantly to the regression, with p values of .05 or less; these predictors made unique contributions to R

2, ranging from .6 percent to 3.5 percent. Of note, psychiatric diagnosis uniquely predicted 3.5 percent of the variance in physical functioning. Participants with diagnoses of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychoses as well as those with depression were predicted to have lower physical functioning scores than those with bipolar disorder or "other" diagnoses.

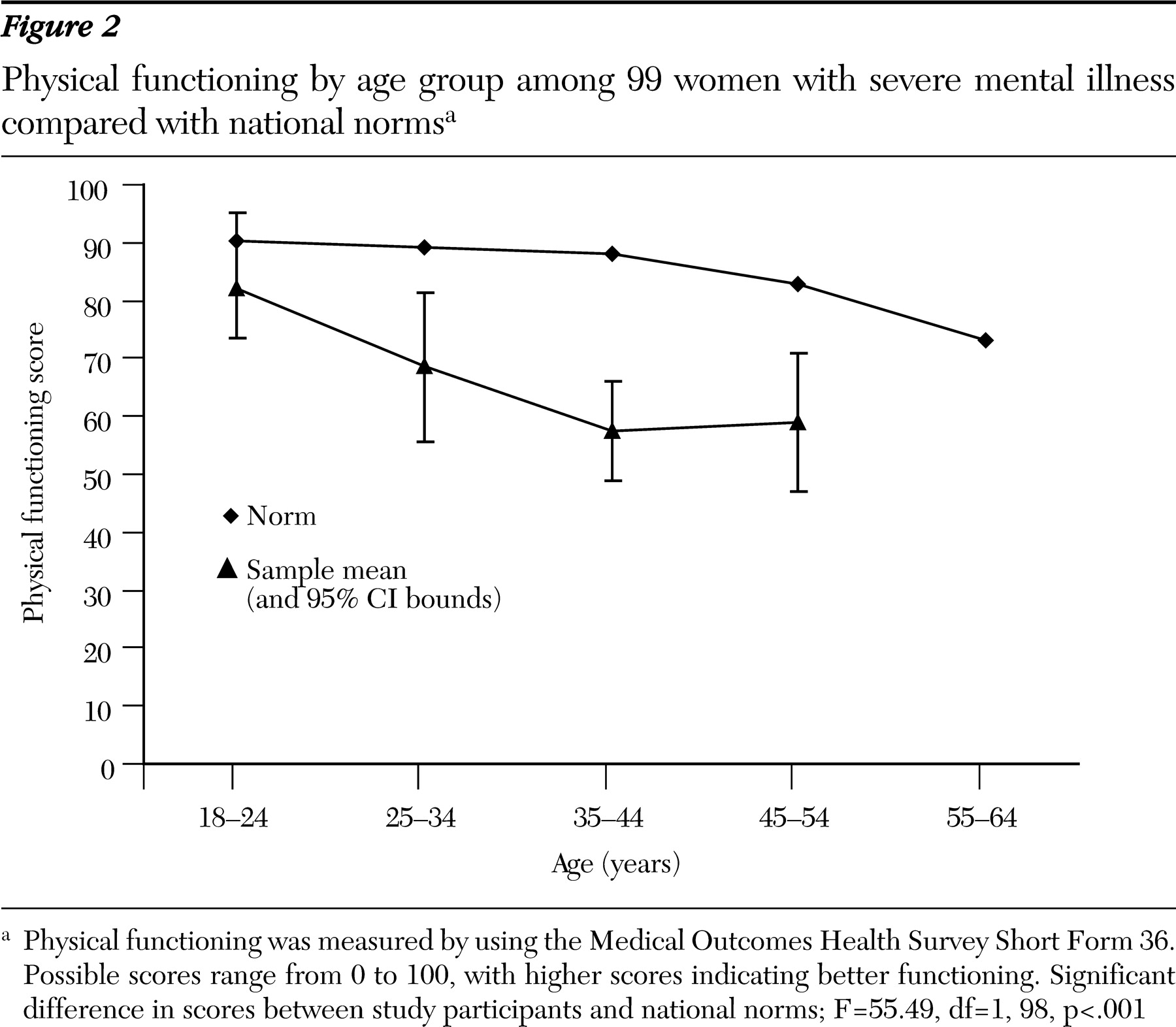

With each ten-year increment in age, the magnitude of differences increased between the mean scores for participants and the scores for the normative groups (

Figures 1 and

2). The mean deviation between the physical functioning score and the normative group mean differed from zero (F=97.03, df=1, 304, p<.001, eta squared=.24), and the test for differences among the study participants' age groups was also significant (F*=4.53, df=4, 60, p=.003, eta squared=.06). Differences from normative groups explained 24 percent of the variance in physical functioning scores; differences among age groups explained 6 percent. Separate analyses were also conducted by age group for each gender, and the results were consistent with this analysis. Therefore, only the overall analysis by age group is reported.

Several post hoc analyses were conducted to describe the findings related to age groups further. Post hoc one-sample t tests were carried out for each age group against the expected mean difference of zero to investigate the significant differences between these groups and the relevant normative groups. We controlled for type 1 error with the Bonferroni correction, using p=.01 for each test. Means for four of the five groups (all but the youngest age group, 18 to 24) were significantly lower than expected, indicating that four age groups from this population reported poorer physical functioning than the norm, even when the analysis adjusted for age. We also examined differences among age groups with post hoc pairwise contrasts by using Dunnett's T3 procedure because of the unequal variances among the groups (

47). We found that even though our sample reported worse physical functioning than the relevant normative groups, participants aged 35 to 44 years and 45 to 54 years reported significantly poorer physical functioning than participants in the 18- to 24-year-old group. Participants aged 25 to 34 and 55 to 64 also reported poorer physical functioning than the youngest group; however, the differences were not statistically significant. Finally, we tested whether the mean deviation scores indicated increasingly poorer physical functioning across age groups and found a significant, decreasing linear trend (F=10.51, df=1, 304, p=.001, eta squared=.03).

Discussion

The demographic characteristics of this sample are comparable to those of adults with severe mental illness described in other mental health systems, with mean ages generally in the late 30s to early 40s (

21,

23,

48,

49,

50). The high ratio of men to women, along with the considerable ethnic diversity and high rates of residential instability and substance abuse, indicate that study participants are similar to clients in programs in urban areas for high-risk subgroups, such as persons with dual diagnoses (

50). It is therefore reassuring that most study participants reported going to a regular place for health care. However, only half saw one provider consistently, and more than half rated their overall health as fair to poor. These global self-ratings are mirrored by their scores for physical functioning.

Determinants of physical functioning scores that were identified in the regression model include demographic factors that are well known to affect health—gender, age, and earned income—in addition to smoking and a psychiatric diagnosis. The fact that we did not identify effects of lifetime substance abuse is puzzling and may reflect the ubiquitous character of abuse histories in this sample. In contrast, smoking has a significant impact on current functioning and probably reflects the relationship between smoking-related problems, such as shortness of breath, and items in the physical functioning scale, which included walking, lifting, and vigorous activities. Diagnoses of depressive disorders and of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (nonaffective psychoses) had the most adverse effects on physical functioning, and the affects did not differ significantly from each other. The comparatively superior physical functioning scores among participants with bipolar disorder may indicate effects of mood on SF-36 self-ratings (

43). The small number of participants in the "other" group had varied diagnoses that may have had less physical impact than schizophrenia and major mood disorders.

The more compelling finding with regard to physical functioning scores in this sample is the magnitude of deviations from national norms for specific age groups. Significant deviations from norms were observed among relatively young adults—those in the third decade of life. Forty-eight percent of our study participants were older than 40 years, and they reported levels of functioning comparable to the elderly in the general population. The mean score for the sample as a whole resembles scores reported anecdotally in other studies of adults with severe mental illness (

34,

36,

37). The mean score is also comparable or slightly better than normative scores for persons with diagnoses of chronic medical illnesses that are prevalent among persons with severe mental illness, including hypertension and type II diabetes (

33). However, these norms are based on chronically ill people who were considerably older than our sample, as indicated by mean ages and the proportion older than 55.

The cross-sectional self-reported nature of these data precludes any conclusions about accelerated physical decline in the population represented by the study participants. Conditions that influenced the health of 35-year-olds in this sample may not be the same factors that produce physical limitations among persons over age 50. Nevertheless, the limitations observed at early ages and the consistent trend for each successive age group suggest decline. Although it is imprecise, we came informally to refer to this phenomenon as "premature aging."

This study had other important limitations. Persons who agree to participate in a clinical trial may differ from other persons with mental illness. Diagnoses were abstracted from clinical charts, and their validity is unknown. Normative data lacked information on sociodemographic factors that often accompany mental disorders. The relatively small contribution of diagnostic factors to the final regression model suggests that these social and behavioral variables may be more important than mental disorders themselves. Further longitudinal studies can elucidate whether mental illness plays a causal role, in the presence of sociodemographic factors, on declines in physical functioning.

Even given these limitations, our findings raise the question of where to set the threshold for receipt of services usually reserved for older adults, including home visits and other supports for personal and medical care. Our findings also underscore the need for early intervention to address the formidable health risks that contribute to poor physical functioning in this population. An extensive body of research in psychiatric rehabilitation demonstrates that adults with severe mental disorders can be actively engaged in their own psychiatric care. Mueser and colleagues (

51) noted that 40 randomized clinical trials have established the value of behavioral, educational, and cognitive-behavioral interventions for selfmanagement of severe psychiatric illness. These models may have comparable value for medical risk reduction, as indicated by recent studies of smoking cessation (

52) and weight control (

53). At this juncture, it appears critical to integrate these approaches into community mental health programs.