Psychiatric advance directives allow competent persons to declare their preferences and leave advance instructions for future mental health treatment or to appoint a surrogate decision maker to act as a health care agent in the event of an incapacitating psychiatric crisis (

1,

2). The legislative intent of laws pertaining to psychiatric advance directives is to enhance patient autonomy at the very time that patients are most vulnerable and in need of high-quality care (

3,

4,

5). Statutes on psychiatric advance directives are designed primarily for people with severe mental illnesses who anticipate periods of decisional incapacity associated with illness relapse. Advocates believe that psychiatric advance directives may improve consumers' access to beneficial mental health treatment during crises and enhance the therapeutic alliance and treatment adherence. In theory, these directives provide a transportable document to efficiently convey information about a patient's treatment preferences and treatment history, including relevant medical disorders, emergency contact information, and side effects of medications (

1,

6).

Although 21 states have passed legislation in the past decade establishing authority for psychiatric advance directives, little attention has been given to emerging policy questions about these legal instruments. Studies suggest that a majority of consumers with severe mental illness would complete advance instructions or obtain a health care agent if given assistance (

7,

8,

9). However, mental health professionals have expressed concerns about these legal tools (

10,

11). In several studies, treatment providers have expressed reservations about practical difficulties in implementing psychiatric advance directives (

9,

10,

12) and the possibility that persons with severe mental illness might use psychiatric advance directives to enforce treatment refusals. This issue was highlighted in the recent U.S. Court of Appeals decision in

Hargrave v. Vermont, which struck down a state law that allowed mental health professionals to override a person's advance refusal of psychotropic medications through a general health care proxy (

2,

5,

13,

14). Despite providers' concerns about the use of psychiatric advance directives to avert treatment, every jurisdiction with specific statutes related to these directives currently permits doctors to override a medically inappropriate treatment preference or refusal.

The extant research raises a number of questions about clinicians' attitudes toward psychiatric advance directives and decision making about following such directives. How do members of different mental health professions—psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers—view laws about advance instructions and health care agents? Do clinicians think that psychiatric advance directives will have a positive, negative, or neutral effect on the delivery of mental health services? What factors do they consider when deciding whether to follow a patient's preferred choice of treatment? How would clinicians decide to follow an advance instruction in which a patient refuses hospitalization and medications? The purpose of this study was to address these questions and to examine clinicians' attitudes and decision making about psychiatric advance directives when working with people with severe mental illness.

Methods

The study gathered attitudinal and decision-making data from a sample of 597 mental health professionals in North Carolina, which included 167 psychiatrists and 237 clinical psychologists who were mailed the questionnaire and 193 clinical social workers who were surveyed online. Data were collected from June 2004 to December 2004. The study was determined to be exempt from human subjects research review by the institutional review board of Duke University Medical Center. A random sample of psychiatrists and psychologists was selected from their state professional organization membership rosters. Because of the difficulty in identifying social workers in psychiatric practice, they were solicited by their professional organization with an online newsletter that included a link to the survey. Among those surveyed, 167 of 518 psychiatrists (32 percent) and 237 of 495 psychologists (48 percent) responded. Post hoc analyses showed no differences between survey responders and nonresponders. The response rate for social workers could not be determined. All participants received a $50 gift certificate after completing the survey.

Measures

Clinician attitudes. Participants were asked whether they approved of North Carolina's laws regarding the use of advance instructions and health care agents for mental health treatment. Participants were also asked whether they thought that psychiatric advance directives would have a positive, negative, or neutral effect on mental health practice and whether they thought that the benefits of psychiatric advance directives could be outweighed by the disadvantage of patients' using psychiatric advance directives to refuse medications.

Legal knowledge. To gauge clinicians' understanding of the legal requirements of psychiatric advance directives, we asked participants whether they agreed with the following statement: "In cases where appropriate medications are refused in a psychiatric advance directive, the law requires clinicians to abide by the patient's refusal." Those who disagreed were correct, in light of North Carolina's statutory provision for doctors to override advance treatment instructions that conflict with community practice standards.

Patient choice and treatment decisions. To elicit information on the factors that may constrain or enhance clinicians' support for patient autonomy in making treatment decisions, participants were asked to rate the importance of the following considerations in deciding to follow a patient's preferred choice of treatment: current cognitive functioning, insight into illness, family support of the patient's preferences, employment, therapeutic alliance and substance abuse and history of psychosis, suicide attempts, violence, and nonadherence to treatment. Participants were asked to rate these according to the following criteria: 1, not important; 2, only somewhat important; 3, important; or 4, among the most important. Ratings of 3 and 4 were coded as endorsement of a factor.

Treatment refusal scenario and decision-making factors. Participants were asked to consider this scenario: "Family members of an individual with serious mental illness bring their relative to the emergency department and request that he be admitted to the hospital. The patient has psychotic symptoms and impaired decision-making capacity but is not dangerous to others or overtly to himself, although he could by statute be committed for his grossly bizarre behavior. You think he can benefit from hospitalization and is insured. Previously, while competent, this patient completed an advance directive refusing hospital admissions and treatment with antipsychotic medications. In this situation, would you probably try to follow the advance directive and not hospitalize this patient involuntarily, even if you personally thought inpatient treatment would be in the patient's best interest?" This phrasing was changed slightly for psychologists and social workers, who were asked whether they would "recommend that the doctor probably try to follow the advance directive."

Participants were then asked, "In your opinion how important are the following factors for such a decision?" These factors included opinions of the patient's family, possibility of a malpractice suit, belief that involuntary treatment does not work, and respect for patient autonomy. Participants rated these either as 1, not important; 2, only somewhat important; 3, important; or 4, among the most important. Ratings of 3 and 4 were coded as participants endorsing a factor.

Clinician characteristics. Descriptive variables included the participants' profession, age, gender, race or ethnicity, proportion of clinical practice involving persons with severe mental illness (more than 10 percent or less than 10 percent), and current work setting (public sector or other).

Analysis

Descriptive and chi square analyses were used to examine categorical differences between psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers in their support for psychiatric advance directives and related attitudes about patient autonomy in making treatment decisions. It should be noted that, as often occurs in the context of survey research, not all participants answered every single question; thus the number of participants who answered questions varies slightly between different analyses and is described clearly in each table.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the relative significance of various factors associated with clinicians' hypothetical decisions about whether to follow the advance instructions in the vignette described above. Independent variables (clinician characteristics, factors that may constrain or enhance clinicians' support for patient autonomy in making treatment decisions, factors involved in deciding whether to follow the advance instructions in the treatment refusal scenario, and legal knowledge about psychiatric advance directives) were regressed on whether participants agreed to follow the advance instructions in the vignette. A total of 510 participants provided these data and were included in multivariate analyses. Variable reduction was accomplished by using stepwise selection with a .10 probability inclusion level. Odds ratios produced by this technique estimate the average change in the odds of a predicted outcome (for example, agreeing to follow the advance instructions) associated with exposure to independent variables (for example, respect for patient autonomy). The log likelihood chi square is provided and tests the overall significance of a given logistic regression model.

Results

Age ranged from 22 to 88 years, with a mean±SD age of 47.3±11.6 years and a median of 49 years. The median age of the sample was 48 years, and most of the sample was white (537 participants, or 90 percent) and female (339 participants, or 57 percent). Exactly half the sample reported conducting clinical work with patients with severe mental illnesses more than 10 percent of the time (298 participants, or 50 percent). A little more than half indicated that they worked in public-sector mental health settings (305 participants, or 51 percent).

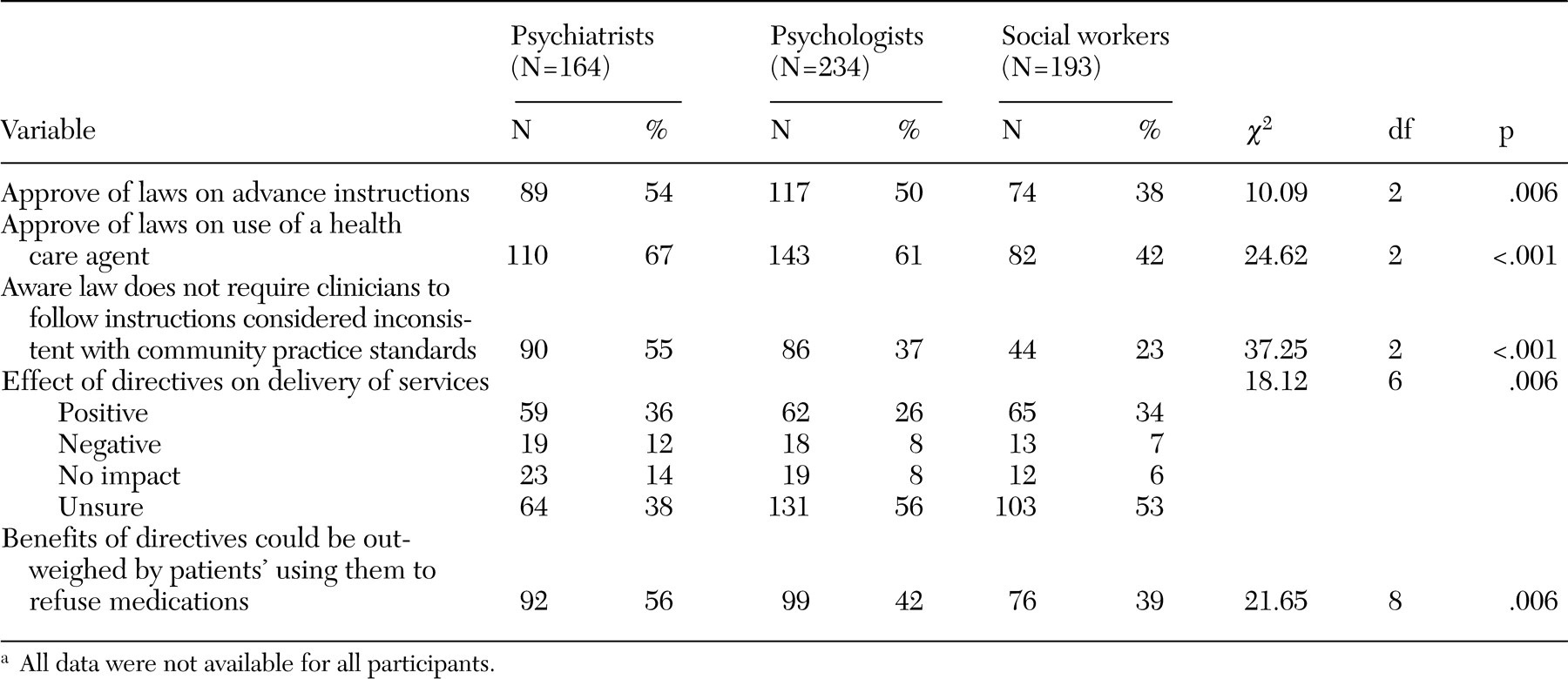

Regarding clinician views of psychiatric advance directives (

Table 1), 280 (47 percent) said that they approved of the state's laws on use of advance instructions, and 335 (57 percent) said that they approved of the state's laws on use of a health care agent. In particular, fifty-four percent of psychiatrists and 50 percent of psychologists approved of advance instructions, whereas only 38 percent of social workers endorsed these laws. HCPA laws were seen more favorably: 67 percent of psychiatrists and 61 percent of psychologists approved of health care agent laws, compared with 42 percent of social workers.

Regarding legal knowledge of psychiatric advance directives, only 220 participants (37 percent) correctly answered the question about whether North Carolina's psychiatric advance directive statute does not require a clinician to follow a patient's advance refusal of treatment that is considered inconsistent with community practice standards. Examining whether there was an interaction between legal knowledge and clinicians' views, analyses indeed did indicate that compared with other participants, those who were aware of this specific parameter of state law on psychiatric advance directives were significantly more likely to approve of advance instructions (χ2=10.2, df=1, p=.001) and health care agent (χ2=9.0, df=1, p=.003) laws.

Clinicians were mixed regarding the effect of psychiatric advance directives. When participants were asked about the likely impact of psychiatric advance directives on mental health practice, 186 (31 percent) reported that they thought the effect would be positive, 50 (8 percent) said that they thought the effect would be negative, 54 (9 percent) indicated that they thought that there would be no effect, and 298 (50 percent) said that they were unsure. Psychiatrists were the most confident in their opinions, with only 39 percent saying they were unsure, compared with more than half of the psychologists and more than half of the social workers who reported that they were unsure.

A total of 267 participants (45 percent) agreed with the statement, "The benefits of psychiatric advance directives could be outweighed by the disadvantage of patients' use of psychiatric advance directives to refuse medications." Even though psychiatrists had generally more favorable views of psychiatric advance directives, they were also the most likely to believe the benefits of psychiatric advance directives could be outweighed by the disadvantage of patients' being able to refuse medication (56 percent).

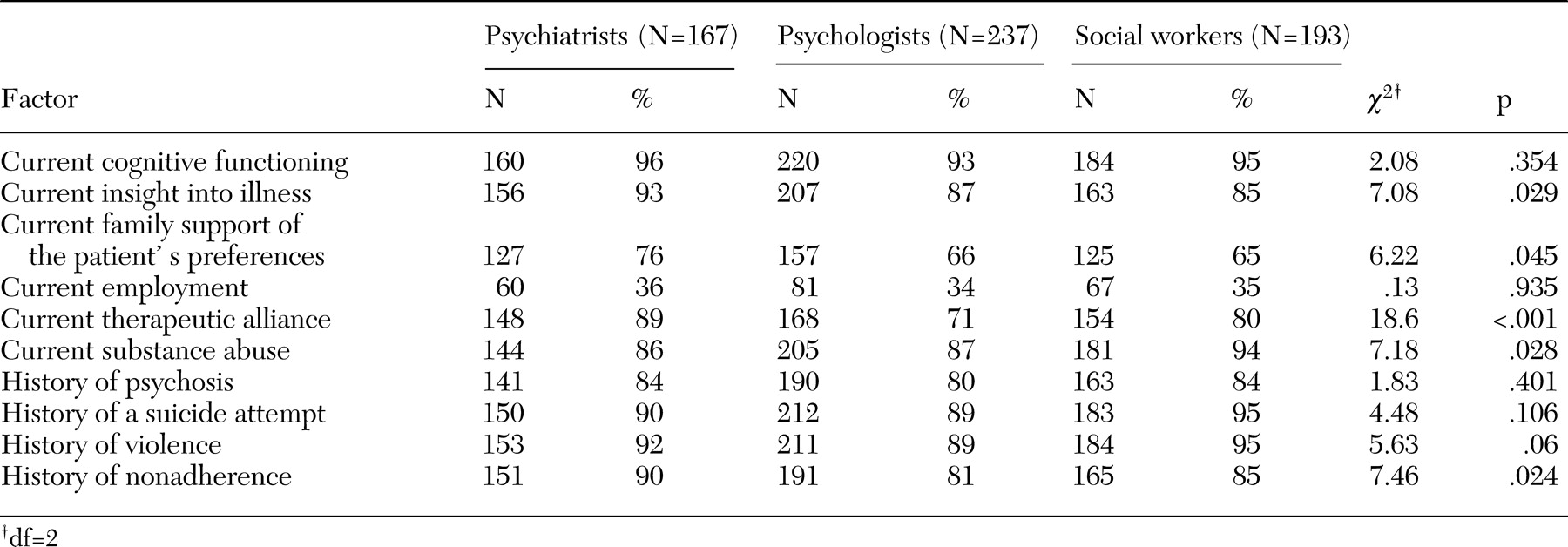

Table 2 shows the frequency of endorsement of various factors that clinicians may consider important in deciding to follow a patient's choices for mental health treatment. Psychiatrists were most likely to endorse the importance of patients' insight into illness, therapeutic alliance, treatment adherence, and current family support of patients' preferences when making this decision. Social workers were most likely to endorse a history of substance abuse as an important variable in deciding whether to support the patient's treatment choice.

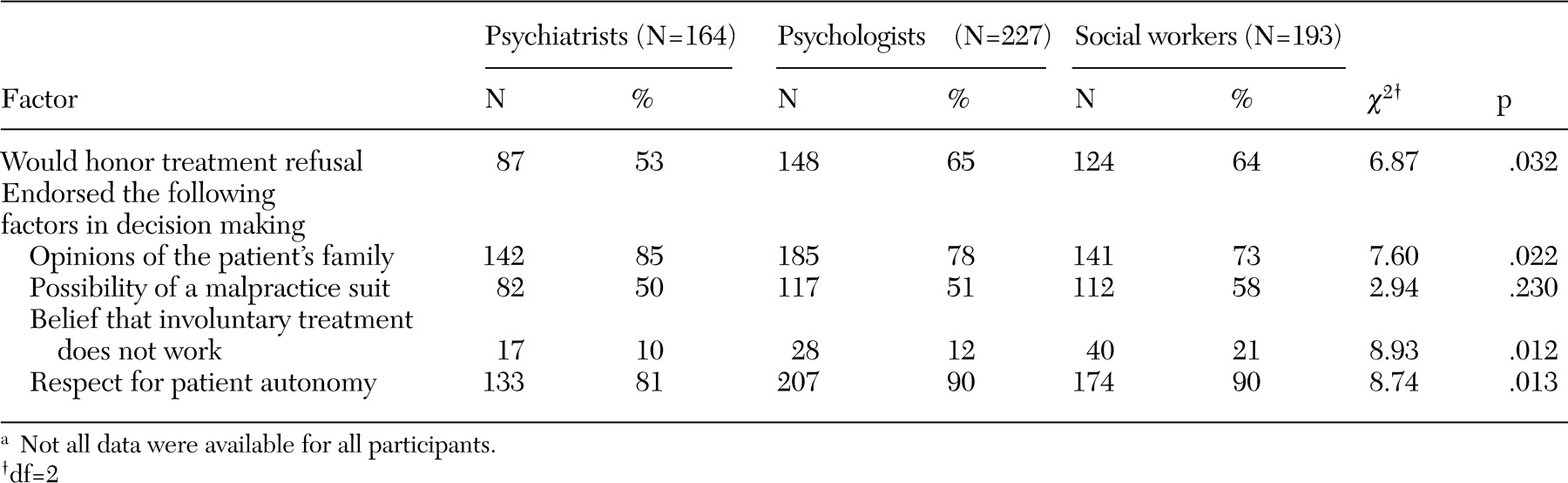

Regarding the treatment refusal scenario described above, 359 participants (61 percent) reported that they would follow or recommend following the patient's treatment refusal in the advance instructions (

Table 3). Fifty-three percent of the psychiatrists said that they would follow the psychiatric advance directive, compared with 65 percent of the psychologists and 64 percent of the social workers. Bivariate analyses showed some significant differences by profession in the factors underlying this hypothetical decision. Psychiatrists were more likely than the other clinician groups to endorse opinions of the patient's family as important and were less likely to endorse respect for patient autonomy. As a factor in their decision, Social workers were the most likely to cite the belief that involuntary treatment does not work. Other clinician characteristics, including gender, age, race or ethnicity, and professional setting, did not relate to treatment decisions made about the scenario.

In multivariate analyses, the net effect of profession was rendered nonsignificant.

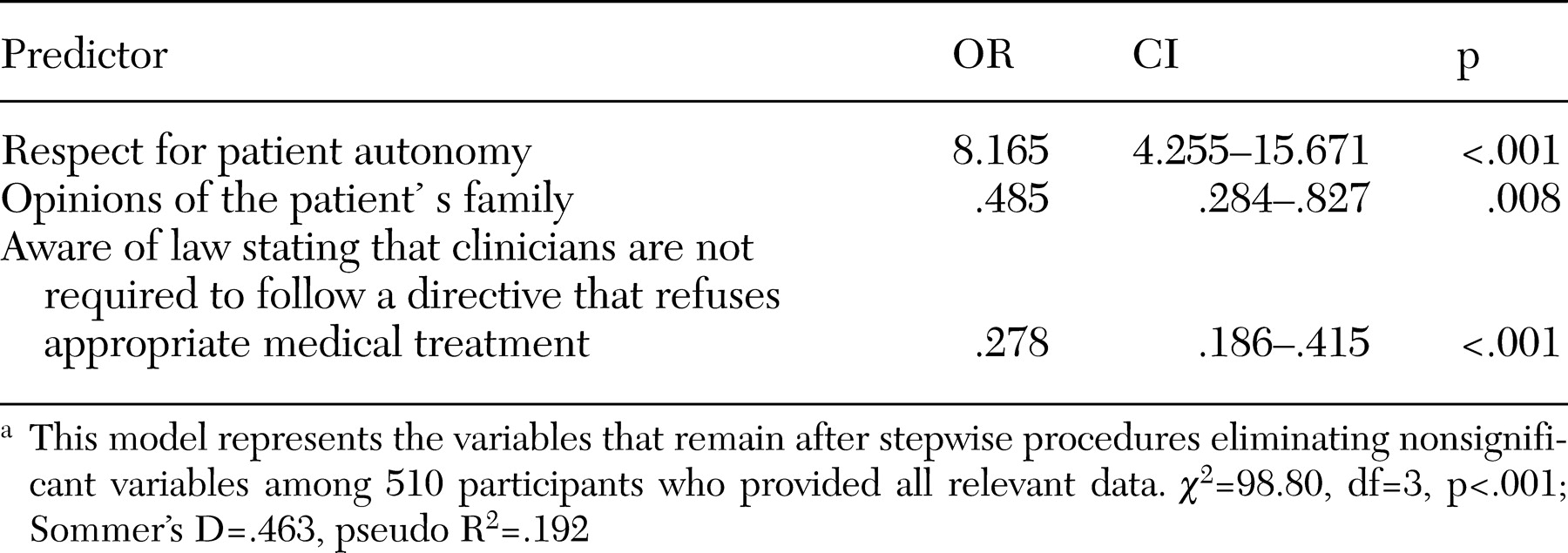

Table 4 displays the variables that remained after stepwise selection of variables at p<.10. Thus several variables did not predict the treatment decisions in the multivariate regression equation: clinician profession, clinician age, clinician gender, clinical work with psychotic patients, working in a public-sector setting, worry about the possibility of a malpractice suit, and the belief that involuntary treatment does not work. Instead, the hypothetical decision about whether to follow the patient's advance instruction that indicated treatment refusal was significantly associated with three factors. First, clinicians who assigned great importance to the wishes of the patient's family were significantly less likely to report that they would follow a patient's treatment refusal in an advance instruction. Second, clinicians who more heavily weighted respect for patient autonomy in their decision making were significantly more likely to report that they would follow the advance instructions that refused treatment. Third, participants were less likely to report that they would abide by the advance instructions if they knew that the law did not require clinicians to follow a patient's advance refusal of appropriate treatment.

Discussion

About half the sample (47 percent) agreed that advance instructions would be helpful to consumers, and a majority (57 percent) indicated that they thought health care agents would be helpful. Regardless of profession, clinicians had more positive attitudes about psychiatric advance directives when they correctly recognized that they were not required by state law to follow advance instructions indicating refusal of appropriate medical treatment. In multivariate analyses, the hypothetical decision to follow a psychiatric advance directive that indicated the patient's refusal of appropriate treatment was positively associated with respecting patient autonomy and negatively associated with legal knowledge and with valuing family opinions about treatment decisions.

The findings imply that many mental health professionals may be unaware of state laws about psychiatric advance directives. This lack of knowledge appears to have significant implications for implementing psychiatric advance directives, because when clinicians in all three professional groups were aware of the parameters of state laws, they tended to have more positive attitudes about psychiatric advance directives. Specifically, if clinicians were aware that psychiatric advance directives cannot legally obligate them to implement patients' inappropriate treatment preferences, then these clinicians were more likely to be in favor of such directives. These findings suggest that clinicians who are adequately informed about the law might be more open to helping patients complete psychiatric advance directives and to asking patients whether they have advance instructions or a health care agent.

Conversely, one may speculate that if clinicians have an incomplete comprehension of the definition and limits of state laws on psychiatric advance directives, they may be less likely to help patients prepare psychiatric advance directives or inquire whether they have such directives. Thus our findings underscore the need to disseminate information about advance instructions and health care agents in states that have these laws. In particular, because consumers with severe mental illness have viewed psychiatric advance directives as clinically useful vehicles to promote self-determination, clinicians who are unaware of laws relating to psychiatric advance directives may thus be missing a therapeutically rich opportunity in which to engage in shared decision making with their patients, which itself may enhance working alliance and treatment adherence.

Interestingly, there were some differences between the three mental health professions regarding the hypothetical decision to follow a patient's preferred choice of treatment: psychiatrists tended to place higher value on family opinions, therapeutic alliance, and patient insight, whereas psychologists and social workers were more likely to endorse respect for patient autonomy. Still, these differences should not be overstated. First, it should be noted that a majority of members from the three professions endorsed the importance of family opinions, therapeutic alliance, patient insight, and respect for patient autonomy. Second, multivariate analyses showed that the profession of the clinician accounted for little variance in decisions about psychiatric advance directives. Instead, the decision to follow advance instructions that indicated treatment refusal was predicted by knowing the related laws, valuing family opinions, and respecting patient autonomy. Clinicians' concerns about the state of the alliance with the family seems especially important if patients have advance instructions and a family member who acts as a health care agent; clinicians would want to know if the family is supportive of the clinician's treatment decisions.

These results suggest that clinicians face complex and often competing values in situations involving psychiatric advance directives, highlighting perhaps one of the greatest challenges to implementing these directives in clinical practice. To illustrate, consider a clinician who values both family opinions about treatment and patient autonomy but finds the family and the patient in conflict. The clinician must balance competing personal ethical values. It may be difficult for clinicians who are overburdened and working in public-sector mental health settings to take the time to discuss and resolve such dilemmas with the parties involved. Gaining a better understanding of how mental health professionals should navigate these issues may thus be a key ingredient in facilitating the implementation of psychiatric advance directives in clinical practice.

With respect to possible limitations of the study, it should be noted that the social work sample involved some self-selection, favoring those who responded most promptly to an e-mail invitation to complete the online survey. However, there is no reason to suspect that this procedure produced a biased sample with respect to attitudes toward psychiatric advance directives. Furthermore, our multivariate analyses controlled for a number of clinician characteristics, including age, experience with severe mental illness patients, work setting, race or ethnicity, and gender.

Conclusions

The findings of this study showed that clinicians who were aware of state law were more likely to endorse psychiatric advance directives. Thus clinicians may be more willing to help clients complete psychiatric advance directives if they are educated about the parameters of implementing these directives. Multivariate analyses also showed that clinicians' profession did not have a major influence on decision making about whether to follow an advance instruction in which the patient refused treatment; rather, clinicians' values and legal knowledge had the greatest effect. This study underscores the complex and often competing values that may enter into clinical decision making when clinicians encounter psychiatric advance directives in practice. The findings also highlight the need for guidance to help clinicians navigate the implementation of psychiatric advance directives, so consumers with severe mental illness optimally benefit from a legal tool designed to foster self-determination. Future research should examine mental health professionals' opinions about advance instructions and health care agents in different states.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Greenwall Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation.