Indeed, some authors have pointed out that religious practices are common among psychiatric patients in Europe (

3,

4) and North America (

5,

6). Up until now, research on schizophrenia has examined mainly religious delusions and hallucinations with religious content, but religion as a coping mechanism has been the subject of growing interest (

7). In clinical practice, clinicians may be reluctant to take this issue into consideration. Several factors may account for the neglect of religious issues in psychiatric practice: an underrepresentation of religiously inclined professionals in psychiatry, which has been noticed among both North American (

8) and British psychiatrists (

9); a lack of religious education for mental health professionals (

8,

10); and mental health professionals' tendency to pathologize the religious dimensions of life (

10,

11). The neglect of religious issues in psychiatry may also be linked to the rivalry between medical and religious professions that stems from the fact that both domains address the dilemma of human suffering (

12,

13).

The study reported here examined the extent to which religion helped outpatients with schizophrenia to cope with their illness. In addition, the importance of religion was evaluated among the patients' clinicians. The degree to which clinicians were aware of their patients' religious involvement and spirituality was investigated. The ease with which clinicians were able to discuss this topic was evaluated, as well as the potential clash between health care and religion, as described by patients. Finally, we evaluated clinicians' understanding of patients' views of this conflict. Our hypotheses were that religion is more important for patients who have chronic psychotic illness and less important for clinicians than in the general population and that patients' religious practices and spirituality are underestimated and neglected by clinicians.

Results

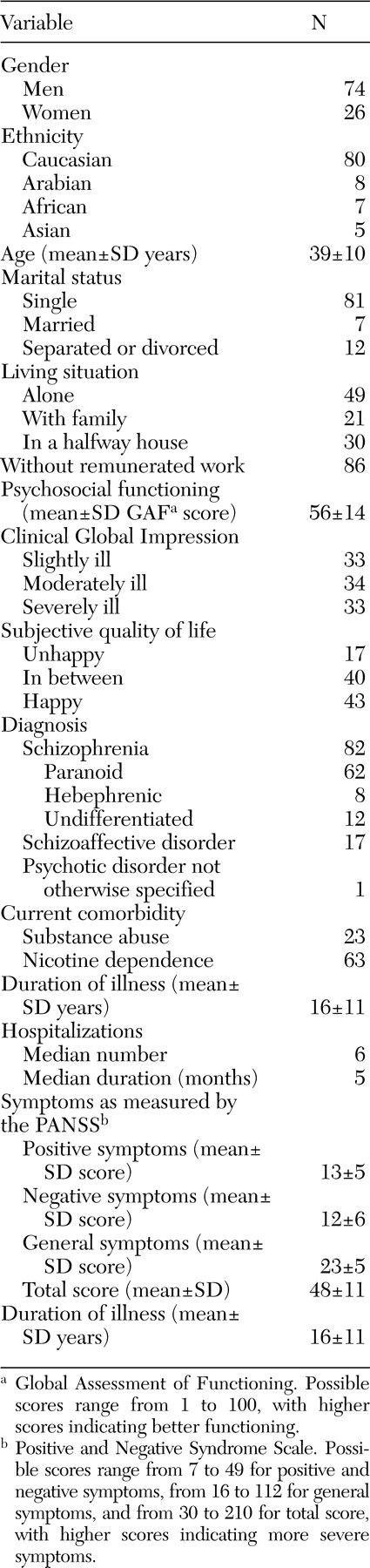

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study are summarized in

Table 1. These characteristics are representative of those of the patients treated in these clinics. Forty, 25, 22, and 13 patients, respectively, were recruited in the four outpatient clinics.

The study psychiatrists were younger than the nurses and social workers (mean±SD ages of 35±6 years, 46±5 years, and 46±11 years, respectively). The gender distribution was equivalent across professions (41 percent male). No significant differences in spirituality and religious practices were found by profession, age, or gender.

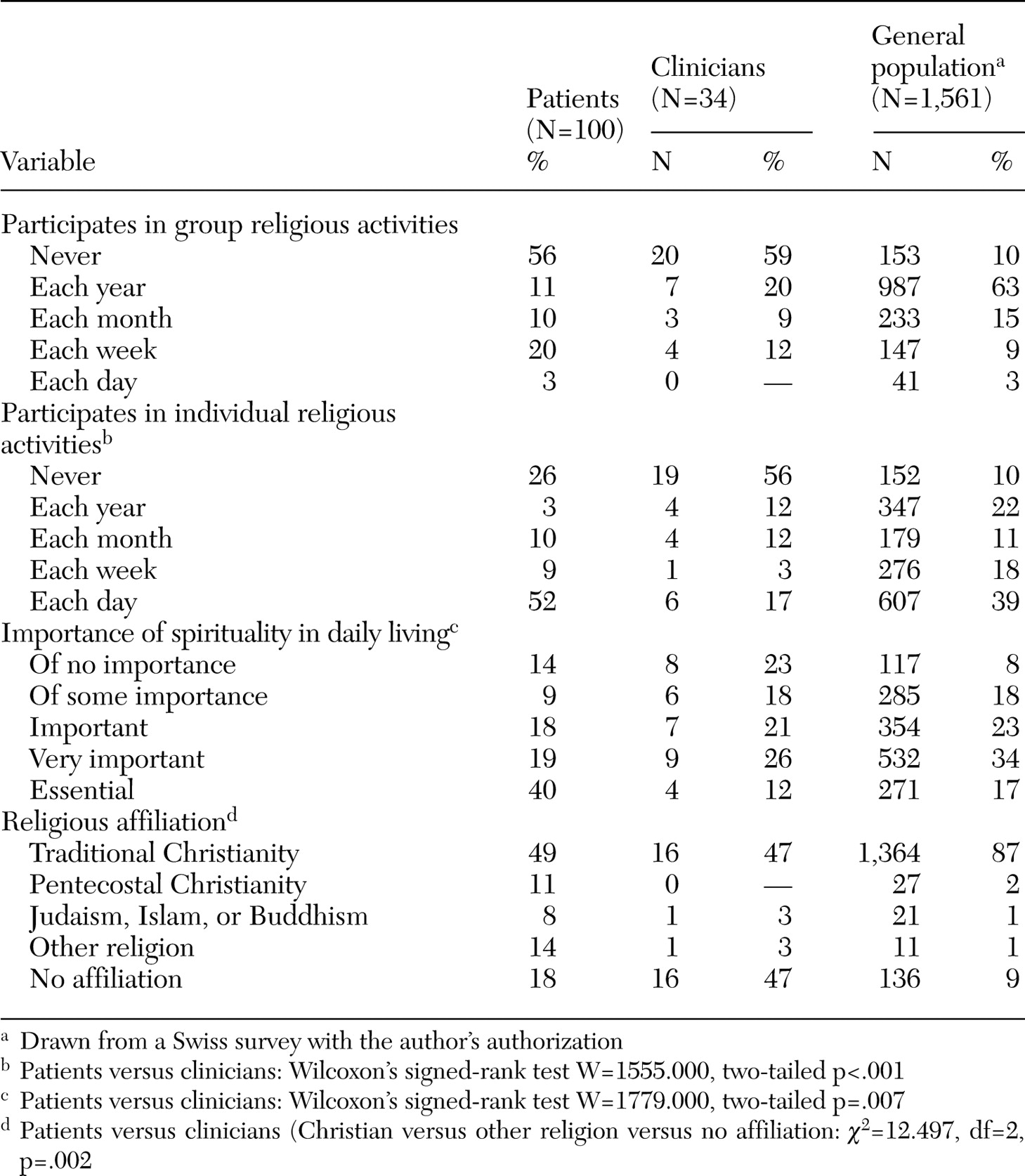

Religious practice and spirituality for patients, clinicians, and the general Swiss population (

22) are described in

Table 2. Most of the general population belonged to traditional Swiss Christian churches (Protestant or Catholic), whereas the study patients were more likely to mention Pentecostal churches, non-Christian religions, minority religious movements (for example, esoterism, spiritism, Christian Science, Scientology, or Ufology) or double religious affiliation (for example, both Muslim and Christian or both Buddhist and Christian). Seventeen percent of the clinicians claimed to be atheist, compared with only 5 percent of the general population. Patients were more involved and clinicians less involved than the general population in individual religious activities. Despite patients' extensive religious involvement, there was no significant difference between patients and clinicians in the extent of participation in religious activities.

The principal components analysis that examined the frequency of religious practices and the subjective importance of spirituality yielded a solution with two factors for patients. The first explained 61 percent of the variance and included individual religious practices with the subjective importance of spirituality, and the second explained 24 percent of the variance and included group religious practices. Thus group activities were weakly correlated with spirituality (Kendall's tau b=.27) and individual activities (Kendall's tau b=.30). Analyses of content showed that these weak correlations were related to psychopathology reflecting aspects of religious belief (16 patients), difficulties in social relationships (24 patients), rejection from religious communities (two patients), and participation in community religious activities without religious beliefs (two patients).

For the clinicians, the principal components analysis yielded a different solution from that of the patients, with one factor explaining 80 percent of the variance. Group activities were highly correlated with spirituality (Kendall's tau b=.65) and individual activities (Kendall's tau b=.72). According to this factor, clinicians were distributed across three groups: those who did not engage in religious practices and did not value spirituality (42 percent), those who did not engage in religious practices but valued spirituality (26 percent), and those who engaged in religious practices and valued spirituality (32 percent).

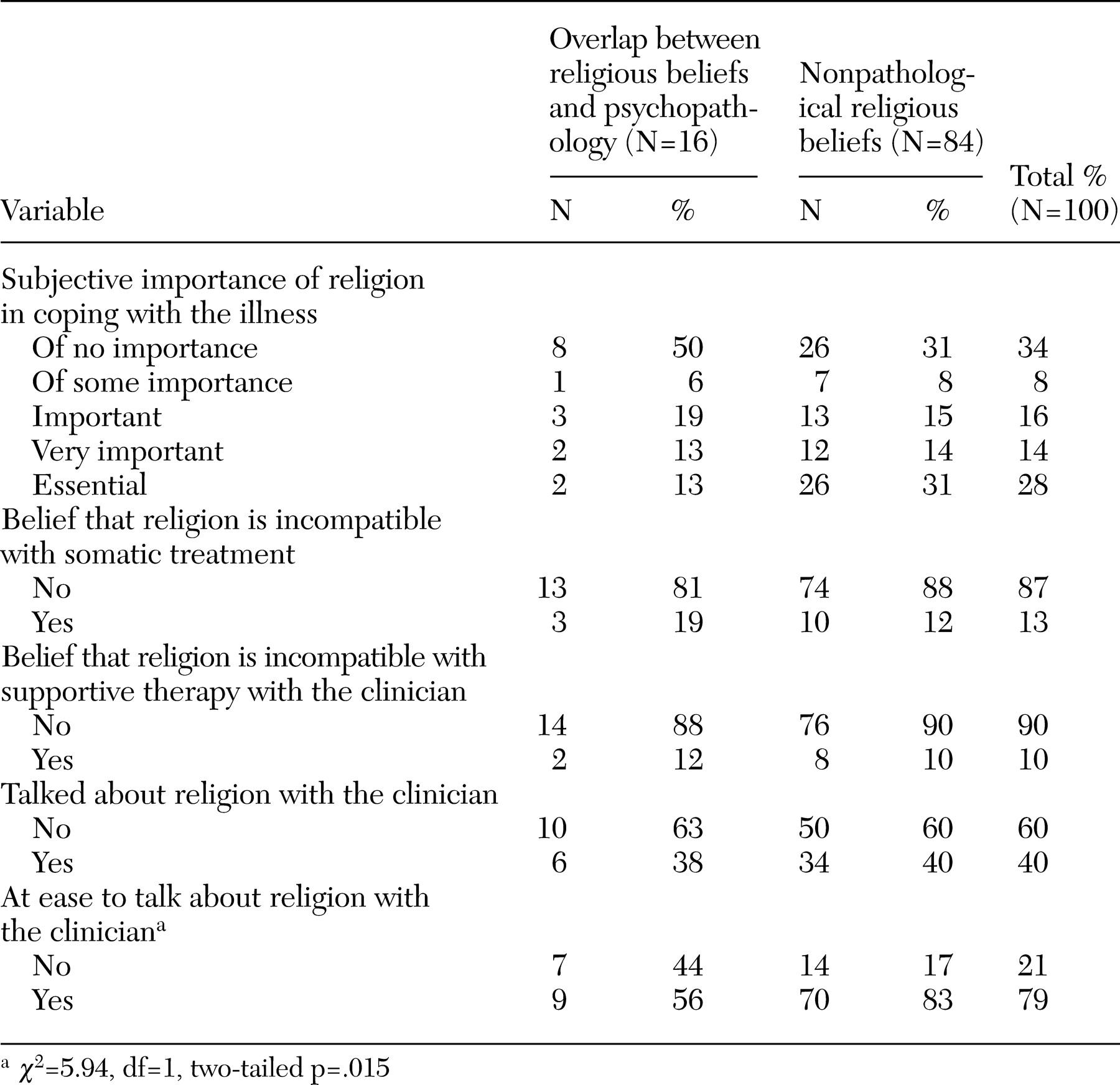

Because religion and psychopathology may overlap, we distinguished patients who had positive psychotic symptoms that reflected aspects of their religious beliefs (N=16) from the other patients (N=84). No differences were found between these two groups in religious affiliation, frequency of individual religious practices, and the importance of religion in daily living and coping. However, none of the patients whose symptoms reflected aspects of religious belief took part in community religious practices.

Table 3 describes religious coping and synergy with psychiatric treatment. Patients whose symptoms reflected aspects of religious belief felt less at ease to speak about religion with their clinicians. For five of these seven patients, this was related to the fact that they feared being hospitalized if they talked about this topic.

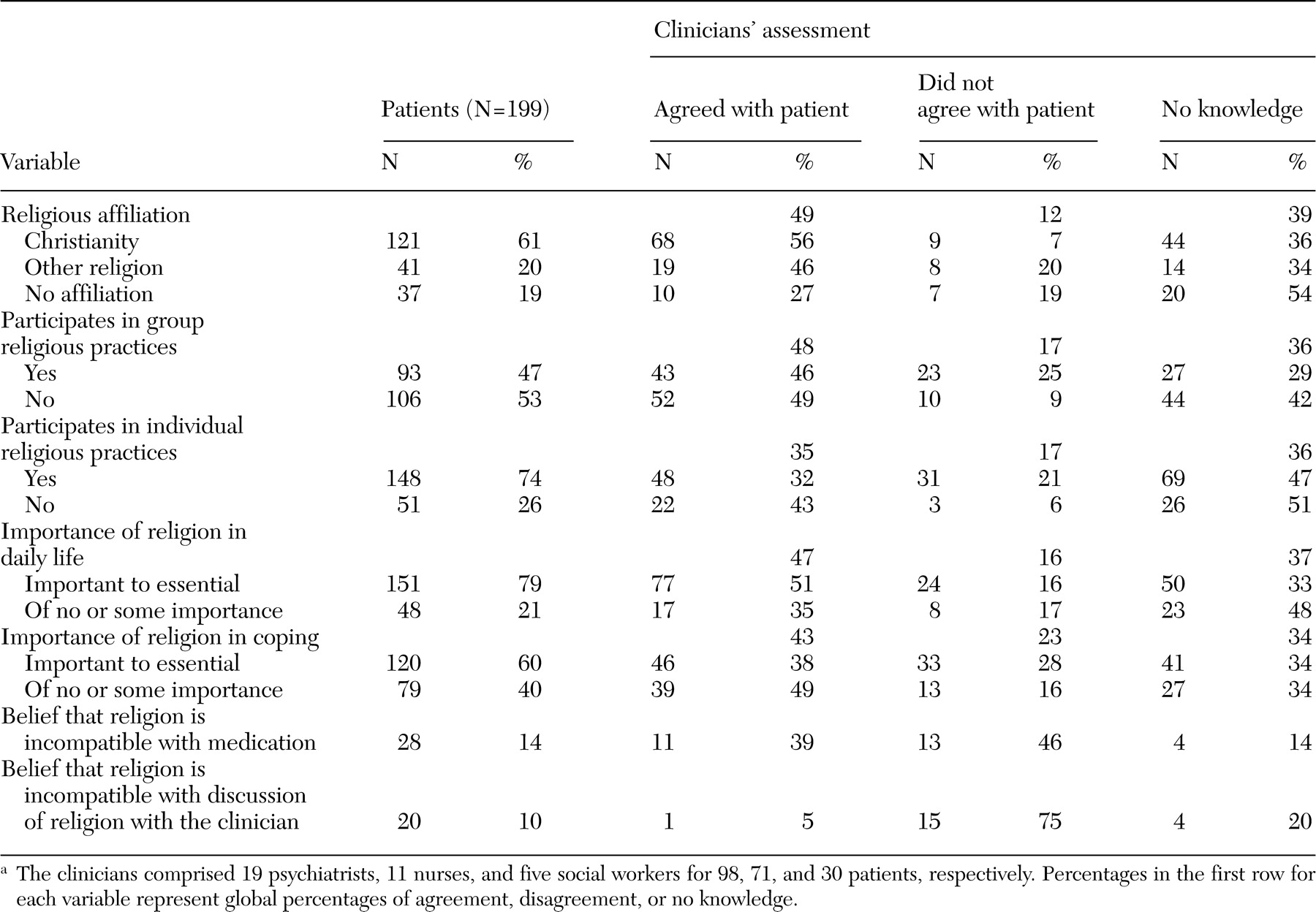

Clinicians' assessments of patients' religious characteristics are summarized in

Table 4. Across the sample, clinicians tended to underestimate the importance of religion to their patients. Clinicians reported discussing religious issues with their patients in only 36 percent of cases, even though they claimed to feel at ease speaking about spirituality in 93 percent of cases. Only six clinicians (17 percent) reported feeling ill at ease with some of their patients. None of the clinicians initiated discussions of the topic themselves. Nineteen clinicians (54 percent) thought that they lacked skills in this domain (data not shown).

A minority of patients perceived a conflict between psychiatric care, medication, and spirituality, but for the patients who perceived these domains as being incompatible with discussions of religious issues, only one clinician was aware of the problem (

Table 4). Clinicians' ease, frequency in discussing religion, and awareness of patients' religious beliefs were not linked to the content of patients' religious beliefs (that is, whether such beliefs reflected pathological or nonpathological thought processes).

Further analyses did not indicate any relationship between clinicians' age and gender and their knowledge of patients' religious beliefs and practices. Psychiatrists and nurses were significantly more aware of patients' religious characteristics than social workers.

For patients whose positive psychotic symptoms reflected their religious beliefs (16 percent), no relationship was found between the clinician's personal religion and the clinician's awareness of the patient's religion. For the other patients (84 percent), different relationships were elicited for psychiatrists and nurses. For the psychiatrists, no relationship was found between their personal religion and their awareness of their patients' religion, with the exception of religion as a way of coping with illness: psychiatrists who were more religiously involved were more sensitive to their patients' religious coping (W=1493.0, two-tailed p=.054).

Nurses' religion was inversely related to their knowledge of patients' religious affiliation (W=845.0, two-tailed p=.041), their representation of patients' ease of discussing religious issues (W=937.0, two-tailed p=.011), and their awareness of patients' beliefs about the compatibility of religion and medication (W=960.50, two-tailed p=.001) and between religion and supportive therapy (W=942.5, two-tailed p=.006).

Psychiatrists' religious involvement was highly and inversely related to their ease in discussing spirituality with patients who had pathological beliefs (Kendall's rank correlation=-.72, two-tailed p<.001) and moderately inversely related to their ease in discussing such matters with the other patients (Kendall's rank correlation=-.37, two-tailed p=.001). For nurses, no relationship was observed between their religiosity and their ease in discussing spirituality with patients.

Clinicians whose religious backgrounds were similar to those of their patients were not more aware of their patients' religion. Psychiatrists and nurses were more aware of patients' religious affiliation only for patients who reported frequent religious practices (W=1205.0, two-tailed p<.001 for psychiatrists and W=536.0, two-tailed p=.001 for nurses). However, for the other patients' religious characteristics, no statistical associations were found with psychiatrists' and nurses' knowledge of them.

Discussion

This study showed, as we expected, that religion was important for a majority of patients suffering from psychotic illness who were treated in the Geneva, Switzerland, area. Health professionals were less religiously involved than the patients they were treating. Patients were characterized by a high level of spirituality, which served as an important coping mechanism. These results are consistent with those of other studies carried out in Europe (

3,

4) and North America (

5,

6). Most patients engaged in religious activities alone; group activities were less common. In particular, principal components analysis showed that, for the patients, group activities were not related to spirituality or individual religious activities. This finding suggests that—as confirmed by the analysis of content—for some patients with schizophrenia, difficulties in relationships and social integration may also constitute a barrier to the fulfillment of spiritual needs.

These results can be compared with those for the general population of Switzerland, as reported in the study mentioned above (

22). Although that survey was different from our research, it nevertheless made an interesting comparison possible and enabled us to conclude that patients with chronic psychosis may be more prone to religiosity than the general population. On the other hand, their clinicians reported the opposite trend, thus confirming other studies that reported an underrepresentation of religiously inclined professionals in psychiatry (

8,

9).

As we hypothesized, clinicians underestimated and often neglected patients' religious practices and spirituality. Psychiatrists, nurses, and social workers did not accurately describe the religious activities and spirituality of their patients: patients' spirituality and group religious practices were correctly identified in half the cases, whereas individual religious practices were identified only for one-third of the patients. Clinicians more accurately described the social dimensions of religion (affiliation and community practices) than the subjective ones, especially religion's relationship with the illness and with psychiatric care.

Some patients expressed the view that religion is incompatible with psychiatric care, but clinicians were rarely aware of this conflict. An analysis of the content of such views showed that some patients believed spirituality to be antagonistic to medication—some invested in spirituality in order to be healed from schizophrenia and refused medication, and others believed that medication hindered spirituality or had diabolic characteristics. Some patients believed that they should not talk about their spirituality, especially those whose religious beliefs overlapped with positive psychotic symptoms. This belief was due mostly to fear of being misunderstood and branded as religiously deluded, which would consequently lead to a risk of being involuntarily hospitalized.

Similar awareness of patients' religious characteristics was found for both psychiatrists and nurses, in both cases related to patients' involvement in religious communities. Clinicians who were more religiously involved did not describe their patients' spirituality and religious practices more accurately, possibly because they felt less at ease to talk about this topic, as indicated by their responses.

Despite these results, a precise explanation of why clinicians were unaware of their patients' religious practices and spirituality cannot be directly established on the basis of our data. A first—but self-evident—possibility is that clinicians broached this topic in only 36 percent of cases. This reluctance is apparently not an issue of feeling uncomfortable with the topic, given that clinicians reported feeling at ease speaking about religion in 93 percent of cases. Further investigation of clinicians' attitudes is necessary to clarify this apparently contradictory situation. It is likely that, in such a survey, clinicians tried to show themselves "at their best," an attitude that may have biased their answer to this question. In addition, a majority of the clinicians claimed a lack of skills in this domain, which led some of them to listen to their patients without going further in the subjective dimension of religion. Patients' attitudes may also play a role. Although a majority don't consider religion to be incompatible with psychiatric care, this topic seems difficult for some patients to share with others, either in religious or medical environments.

Our study had some limitations. Although the number of patients in the sample made it possible to report credible results, especially given that the patients were treated in four different outpatient clinics, the smaller number of clinicians casts doubt on the accuracy of the data for the clinician sample. In particular, the data for the social workers should be considered as exploratory given the small number of social workers. Similar studies should be repeated in larger geographic areas, given that, in order to have a sufficiently large sample, we needed to include almost all psychiatrists and nurses employed in public outpatient clinics in Geneva who worked with patients treated for chronic psychosis. Finally, religion's cultural aspect should be kept in mind, and our results should be considered in the particular context of this part of Switzerland. However, even though further studies may be needed on clinicians' representations of their patients' spirituality and religious practices, our results for both patients and clinicians are consistent with those of studies conducted in other countries.