The Psychotherapy Supervisor as an Agent of Transformation: To Anchor and Educate, Facilitate and Emancipate

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Highlights

Learning in supervision is transformational (not just transmissional) (1).

Why Have a Psychotherapy Supervisor at All?

Purposes of Supervision

Impact of Supervision

Supervision and the Beginning Supervisee

The Beginning Supervisee, Liminality, Boundary Confusion, and Edge Emotions

The Supervisor Leaning Into Liminality and the Edge Emotions

Building Transformative Learning Possibilities in Psychotherapy Supervision

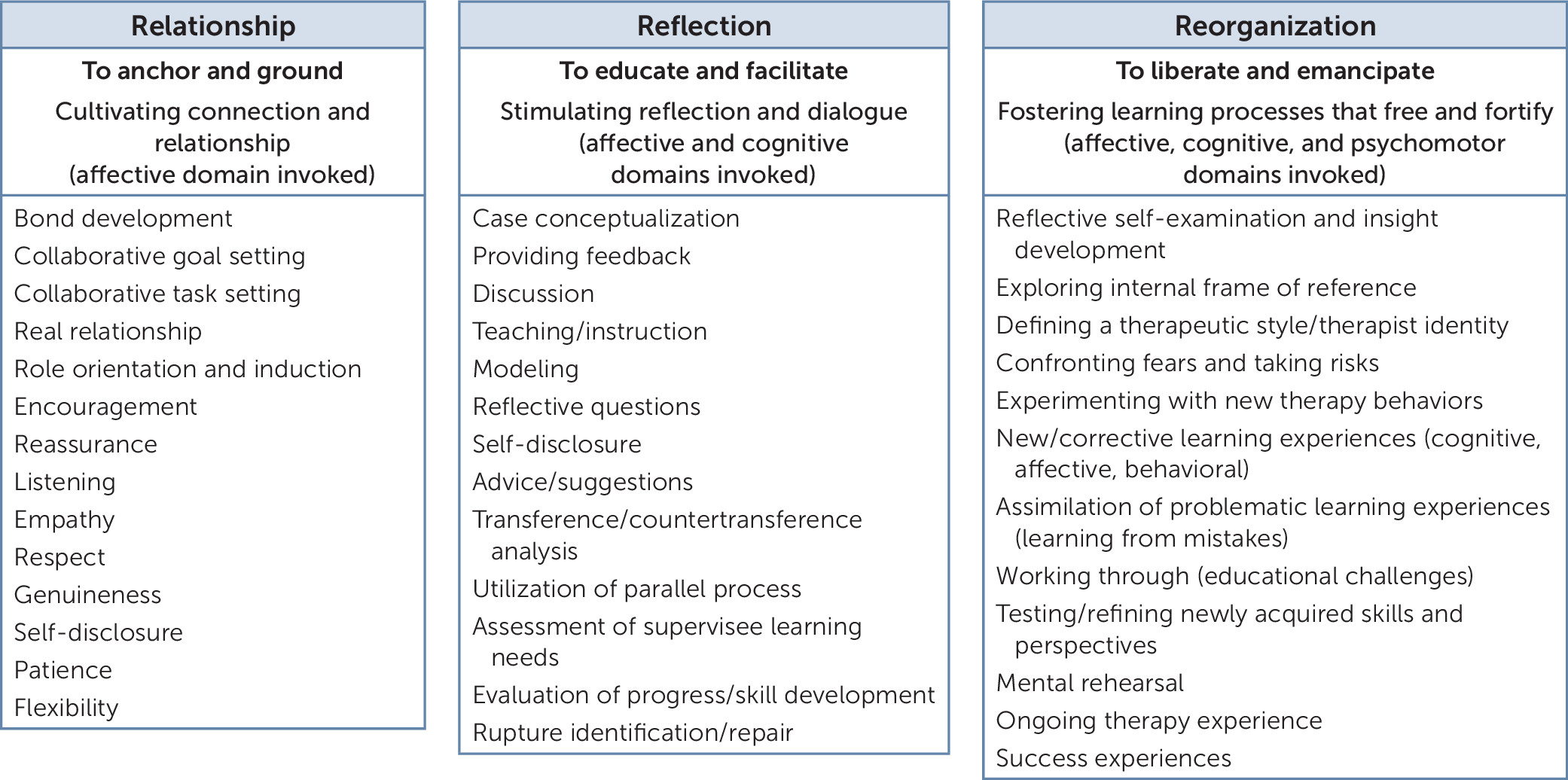

To Anchor and Ground: Cultivating Connection and Relationship

The supervisory alliance.

The real relationship.

Supervision role orientation and induction.

Supervisor facilitative conditions and behaviors.

To Educate and Facilitate: Stimulating Reflection and Dialogue

To Liberate and Emancipate: Fostering Learning Processes That Free and Fortify

Cultivated Connection, Realized Reflection, and Evolving Emancipation

Conclusions

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).