Such examination and demands occur in the context of crucial demographic and clinical shifts in the context of dying. With the remarkable success of 20th-century medicine and public health efforts, most life-threatening acute diseases in younger persons have been prevented or controlled, such that 80% of deaths in the United States now occur among persons age 65 years and older (

5). Concomitant with this, the majority of deaths also occur in the setting of chronic illnesses associated with functional decline. Partly related to these shifts, we have seen the so-called “medicalization” of death in our society (

6). Concerns raised about such medicalization include fears that suffering will be worsened or prolonged by medical procedures or treatments, as well as recognition that death is often removed from the contexts (i.e., social, cultural, religious) that in former generations helped give the dying process meaning for the terminally ill person and her or his family. Indeed, despite the fact that 90% of Americans would prefer to die at home (

7), 60%–80% actually die in institutional settings (

5,

8,

9), often in the context of invasive procedures, artificial support of basic human functions (e.g., nutrition, ventilation), or resuscitation efforts.

Palliative “versus” curative or disease-focused care

Much of modern medicine targets treatments at disease cure, or at least at limiting or slowing disease progression. In so doing, improvement in the patient’s symptoms or functional status are welcome and expected byproducts of the disease-focused treatment. By contrast, the paramount goal in palliative care is alleviation of symptoms or functional morbidity, that is, suffering. Improvement in the underlying disease process is not expected, or is attempted only in the interest of reducing suffering, without expectations of prolonging survival. Therapies that produce discomfort are not attempted, or are abandoned when the suffering produced exceeds the relief provided.

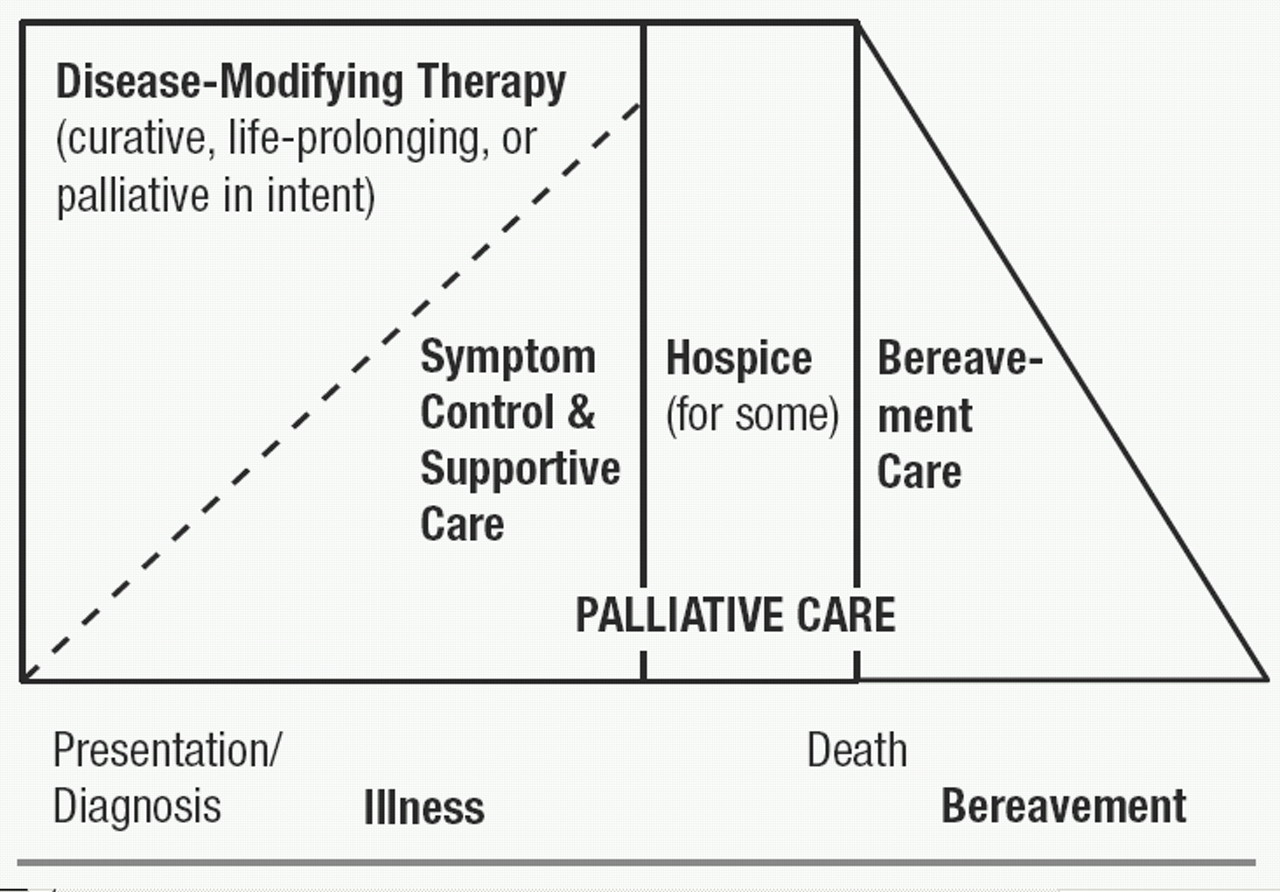

It is important to recognize, however, that the distinction between palliative and disease-focused care is often arbitrary. Symptom reduction, of course, may be a direct result of curative therapy, or may be the result of allied therapies administered concurrently. Conversely, disease-focused treatments may be the best approach to palliation in some situations. It may be argued that “traditional” medical management of many chronic diseases is, in reality, palliative in goals and scope. Even in the context of life-threatening diseases, palliative and disease-focused approaches to care often coexist. There may be a gradual transition as the disease progresses, curative interventions fail, and death approaches, as depicted in Figure 1.

Thus, palliative care does not apply solely to those facing imminent death. Indeed, discussions with patients and families about palliative approaches ideally take place relatively early in the course of a life-threatening illness (

19), and such discussions should be revisited as often as indicated by changes in the patient’s condition, wishes, or care options. The timing and shape of such discussions also will be affected by the varied “trajectories” toward death (

8,

20) produced by different diseases, for example, relatively slow or predictable decline (often seen for example in neurodegenerative dementias, cancers, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), or courses marked by more acute exacerbations, any one of which might lead to death or to partial or even full, if temporary, return to baseline, for example, as often seen in pulmonary or cardio- or cerebrovascular diseases.

Figure 1 also indicates that some patients may die after a discrete period of hospice care, that is, a purely palliative approach provided within a clinical, organizational, or funding framework designated as “hospice.” The designation as hospice care depends partly on patient (and provider) decisions to explicitly focus on a purely palliative approach, and partly on disease course; for example, funding for hospice may depend on the physician’s ability to state that the patient is highly likely to die within an arbitrary time-frame. Figure 1 also refers to “bereavement care” after the patient’s death (note the section below on the role of supportive contacts with the family to reduce or prevent subsequent psychiatric morbidity).

All physicians should be versed in the basic tenets of palliative care, along with more specific aspects relevant to their specialty. Training in palliative care during medical school and residency historically has been inadequate, but curricula are increasingly changing to reflect this need (

21,

22). Palliative care also has achieved formal specialty status in many nations, recently including the United States.

Talking with patients and families about end-of-life care

Application of our interview skills is particularly crucial, challenging, and rewarding with dying patients and their families. As previously noted, discussions about end-of-life care should begin relatively early in the context of severe debilitating or life-threatening illness. These discussions provide a base upon which to continue discussions as the disease progresses, and often increasingly complex or urgent decisions need to be made about care options. Such “end-of-life conversations” (

19) should become routine, structured parts of interventions in health care, as guided both by clinical experience and by growing empirical evidence that these discussions improve outcomes such as elicitation of and adherence to patient wishes (

23).

First discussions should begin with the use of open-ended questioning to understand the patient’s lifelong values and views on illness, suffering, medical treatments, and death (

24–

26). This approach may include queries such as, “Tell me about yourself . . . about your past experiences with illness . . . with doctors or medical treatments . . . .” It is critical to convey empathy and a clear message that the care-provider will 1) respect the patient’s wishes, and 2) not abandon the patient, even (especially) if or when disease-focused treatments no longer prove effective (

27,

28). It is also important to help the patient understand the concept of palliative care, especially that a palliative approach may coexist with (i.e., is not necessarily the opposition of) disease-focused care. Elicitation of values and wishes must include an appreciation of the patient’s cultural context (

29), including the family system (

30), as well as an understanding of the role religion or spirituality may play in the patient’s values and choices (

31). All of these discussions should help the patient articulate, and the physician understand, his or her own personal definition of “death with dignity,” so that future interventions may help conserve that dignity (

32,

33). Geriatric psychiatrists have particular experience in assisting patients and families conduct life review and reminiscences, which may be a therapeutic part of the interview process as well as a “diagnostic” aid to understanding the patient’s personality, values, and priorities. For example, some persons who have always valued self-reliant independence might choose to assertively “fight” their illness until the end, whereas others might choose to forgo certain treatments (curative or palliative in intent) with an eye toward living their remaining days as autonomously as possible. Also, the geriatric psychiatrist should use her or his skills to understand the ways in which the patient’s religious or spiritual beliefs affect their decisions, serve as a framework for seeking meaning during the final phases of life, or suggest additional sources of support (i.e., clergy or members of the patient’s religious congregation) (

31).

Further and ongoing conversations with the patient will include other elements, including

1.

Delivering bad news: As the disease progresses, complications develop, or disease-focused treatments fail, the patient and family must be informed of the relevant facts in a manner that fosters the treatment alliance and continued partnership in decision-making (

34,

35). A useful approach is to let the patient know up front that there is bad news to be delivered, and to assess their readiness to engage in the discussion. For example, in the case of an MRI scan that newly reveals evidence for metastatic spread in a cancer patient previously thought to be in remission, one might say, “I’m sorry to say that I have some bad news from the results of your MRI scan. Would you like to talk about that now?” In situations where the news to be delivered is less unequivocally “bad,” one might choose more neutral language that does not preemptively interpret the patient’s response to the information provided; for example, “I have the results of your MRI scan. Would you like to talk about that now?”

2.

Eliciting history: It is important to continually reassess the patient’s symptomatic status, to inform therapeutic and palliative interventions. Ask directly about pain, as described more below. Make specific inquiries about other relevant physical and emotional symptoms (also see below), as well as functional status and interpersonal needs. Again, geriatric psychiatrists have well-developed skills at eliciting the relationship of physical and emotional skills to functional abilities and resource needs (interpersonal and instrumental). A number of factors may make symptom elicitation difficult. For example, some patients may be reluctant to acknowledge symptoms out of ignorance that these can be alleviated, or out of fear that such disclosure will lead to the discovery of more “bad news;” thus the above-noted educational and alliance-building approaches are crucial for forming the context within which symptoms may be elicited. As another example, the high prevalence of cognitive deficits—from delirium or dementia—among dying patients may require careful attention to the patient interview, and involvement of family or other caregivers, to elicit relevant symptom history.

3.

Decision-making: Inevitably, the patient and family will have to make decisions about care options. These may include decisions about whether to continue or pursue disease-focused treatments that may have some potential to extend life or slow the disease process, combined with a high potential to increase suffering. Decisions about emergency interventions, including mechanical ventilation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, are too often made in crisis rather than ahead of time. Patients, families, and providers sometimes collude in avoiding discussion of these emotionally-laden topics during times of clinical stability, yet it is just such times that provide the opportunity for thoughtful conversations. The physician needs to bring these topics up, perhaps introducing the discussion with process comments; for example, “I’m glad that you are feeling well today. I do think that at some point we should talk about the kinds of treatment options you might have if your illness worsens down the road, including what kinds of treatments you might want or not want. Would you like to talk more about this today?” As the discussion continues, the physician should frame the decision-making by providing needed information in a manner that is accurate and complete enough to facilitate the patient’s arriving at a decision consistent with his or her value system. Indeed, there is evidence that ill older patients can make health-utility decisions balancing competing considerations (

36). At the same time, choice of words and frame are crucial. For example, patients are more likely to choose palliative approaches over life-extending care if they have a more accurate understanding of their prognosis, or of the (often low) likelihood of meaningful recovery after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (

37,

38).

In the context of a strong therapeutic alliance, patients and families may ask difficult questions (“How long will I live, Doc?”), or may assert wishes as facts that contradict our best professional estimates (“I’m going to beat the odds and live to see my grandson graduate from high school next year.”). Useful responses often will incorporate elements of conveying empathy for the process underlying the patient’s statement (e.g., “That graduation is pretty important to you; it’s hard to think that your heart condition might prevent you from being there.”), and statement or re-statement of the relevant facts along with factual acknowledgement of our professional uncertainty (“Unfortunately most people with your stage of heart disease do not live more than 3 to 6 months, although there are rare exceptions.”). Use of “I wish” statements can be a useful way to communicate empathy along with the prognostic facts (“I wish I could tell you that you were likely to live that long.”), and “if” comments may help facilitate needed planning discussions (“We can hope for the best, but if it turns out to be the case that you die before the graduation, how would you like to have spent your last months with your grandson?”) (

24,

39). Skills at conveying empathy and aiding future planning are, of course, part of the repertoire of mental health clinicians (as well as well-trained practitioners from other specialties), and those with geriatrics expertise are experienced at such work in the context of medical comorbidity and disability.

Relieving suffering

Distressing symptoms in dying patients may occur as part of dysfunction in any organ system. Some may represent underlying medical emergencies, to which decisions must be made as to the level of interventions attempted. Common symptoms most relevant to psychiatry include the following:

Pain. Physical pain is among the most common symptoms in dying patients, and among the most feared by patients and families. The control of pain is a crucial topic, one that requires more space and has received it elsewhere (

40–

43). Geriatric psychiatrists, in common with colleagues in consultation psychiatry as well as other subspecialties, should have expertise in the assessment and management of pain. Some basic tenets of pain control are listed here.

1.

The goal is to eliminate pain. For most patients, it is possible to achieve this goal fully, or at the least to reduce pain to tolerable levels without intolerable side effects. There are some patients who do not want to have their pain eliminated. In this event, careful discussion should elicit whether this wish arises out of, for example, (actual or feared) side effects of analgesics, depression-related hopelessness, or the patient’s religious or other cultural values precluding acceptance of pain treatment; in the latter case, exploration with the patient and family can determine whether there is any flexibility within the value/belief system.

2.

Pain must be routinely assessed. This is best done by direct inquiry, asking the patient to rate pain on a scale of 0–10 (or by using an equivalent visual-analog scale when verbal communication is difficult); such inquiries may be included in routine nursing assessments as the “fifth vital sign.” It must be recognized that there is no substitute for such direct inquiries of pain ratings by the patient. Observer ratings frequently under-rate pain, partly because chronic pain may manifest as depression, irritability, or other nonspecific symptoms rather than as the visible discomfort we expect to see in acute pain. Because depression so commonly exists concurrently with pain, and may color perceptions of the pain or treatment options, depression must be assessed as well; see below.

3.

In many cases, optimal pain treatment may include “disease-focused” therapies, whether or not the use of such therapies can be expected to improve survival or overall disease progression. Common examples include anti-anginal drugs for angina pain, radiation therapy for bony carcinomatous metastases, or glucocorticoids to reduce pain associated with inflammation and edema.

4.

Analgesic drugs are a mainstay of pain control. A systematic approach to drug choice should be applied, using a fixed-dose regimen to provide around-the-clock relief along with prn (or “rescue”) medications for break-through pain. The regimen should be reevaluated frequently and increased (in frequency or dosage) if break-through pain is present more than rarely. The World Health Organization analgesic ladder should be used to choose drug class on the basis of severity of pain (

41,

44). Options for Step 1, mild pain, include acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (including aspirin and the COX-2 inhibitors). For Step 2, moderate pain, opioids such as oxycodone or codeine are given, typically in combination with a Step 1 drug. For Step 3, severe pain, opioids such as morphine are the treatment of choice. Route of administration will depend on the drug, the patient’s ability to swallow or absorb an oral dose, and convenience of access to other routes (e.g., nasogastric or direct enteral access, permanent intravenous ports). For some drugs and clinical situations, continuous administration, for example, a subcutaneous morphine drip, with patient control of the dose may be most appropriate.

Other drugs may provide analgesia for certain types of pain. For severe bone pain due to metastatic cancer, co-administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) along with opioids is often effective (

45–

47). There is some empirical evidence to support the use of other adjuvant drugs in refractory bone pain; these include corticosteroids, biphosphonates, and calcitonin (

48–

52). For neuropathic pain syndromes refractory to opioids alone or co-administered with NSAIDs, empirical evidence best supports the use of tricyclic antidepressants (

53,

54). There is limited evidence for the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and even more limited data for other antidepressants, including venlafaxine, bupropion, and mirtazapine (

54–

58). The use of anticonvulsants is commonly recommended as well, although the empirical evidence for indications other than trigeminal neuralgia, and for agents other than carbamazepine, is limited at best (

59). Many other agents have been recommended for neuropathic pain, each with very limited evidence, especially as applied to terminal-illness contexts (

60–

65).

Side effects may limit the tolerability of analgesics. Common problems with opioids include nausea, constipation or obstipation, and sedation or other neuropsychiatric symptoms (e.g., perceptual disturbances with or without the presence of full-fledged delirium). Sometimes switching to a different opioid allows achieving adequate analgesia with fewer side effects in a particular patient. Combination of opioids with other classes of analgesics may allow reduction in opioid dosage with still-adequate pain control. In some cases, additional drugs may be used successfully to counteract opioid side effects, for example, the common prophylactic use of laxatives to prevent uncomfortable constipation or the use of psychostimulants to reduce opioid-induced sedation (

66,

67).

Non-pharmacological approaches to pain may provide benefit in selected individuals and are widely used, although the empirical evidence for their efficacy varies widely, depending on the condition and the modality (

68,

69). These approaches range from invasive (e.g., anesthetic or surgical interventions) to noninvasive physical modalities (e.g., physical rehabilitation approaches, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, massage) to cognitive/interpersonal approaches (e.g., meditation, guided imagery, relaxation techniques). Geriatric psychiatrists may use their skills in such psychotherapeutic options as guided by patient preferences.

Depression. It is well recognized that depressive symptoms and syndromes have clinically important bi-directional relationships with comorbid medical conditions. Indeed, medical illnesses are among the most consistently identified correlates of the presence and course of depression in later life, while, conversely, depression is a powerful predictor of functional outcomes and mortality in broad populations. as well as in many specific chronic medical diseases (

70,

71). The clinician or researcher seeking to diagnose depression in dying patients may face confounds in symptom assessment familiar to geriatric psychiatrists, who have expertise working with depression in medically ill patients—namely, how to “count” neurovegetative symptoms (e.g., anergia, anorexia, weight loss, sleep or psychomotor disturbance) toward the syndromic diagnosis of depression, when such symptoms may be due to underlying medical disease even in the absence of depression. Although DSM-IV asks clinicians to take an “etiologic” approach in practice, it is often difficult to judge whether the medical disease or depression causes a particular symptom. Other diagnostic approaches have been described, including exclusive (i.e., eliminating potentially confounded neurovegetative symptoms), substitutive (replacing confounded neurovegetative symptoms with additional emotional or ideational symptoms), or inclusive (counting all symptoms toward the depressive syndrome, regardless of potential etiological confound) (

72). For research purposes, a multi-institutional work group recommended the inclusive approach, based on reliability considerations as well as prevalence and prognostic validity studies that fail to confer a clear advantage for one approach over another (

73). However, many clinicians working with dying patients continue to recommend an essentially exclusive approach, that is, an emphasis on the emotional and ideational symptoms of depression (

74). Even assessments of the latter symptoms are difficult in palliative care contexts, because it is not clear how to operationally define some ideational symptoms, such as hopelessness or recurrent thoughts of death, in persons facing impending death. Moreover, the conceptual, definitional, and therapeutic issues regarding minor and subsyndromal depressions, murky enough in broader patient populations (

75–

78), remain largely uncharted territory in dying patients.

Given such limitations, along with the difficulties in conducting psychopathological research in dying patients, the empirical research literature on depression in dying patients is relatively small, limited largely to cancer and HIV patient populations. Still, the findings are generally comparable to those seen in broader medical illness groups. The following are important “take-home” points about depression in dying patients:

1.

Depressive symptoms and syndromes are common in dying patients, although the range of estimated prevalence rates (approximately 15%–60%) likely reflects the heterogeneity of depressive conditions and their definitions as well as the patient populations (

79–

82).

2.

As in primary care and other broad settings, self-reported depression inventories, including the singleitem question “Are you depressed?”, have good operating characteristics as screens for diagnosable depressive disorders (

83–

85).

3.

Evidence from patients with cerebro- or cardiovascular disorders (

86,

87) or cancer (

88) suggest that depressive conditions in dying patients are multifactorial in origin, representing a combination of physiological effects of the disease process on brain functioning, premorbid diathesis toward depression, and current psychological and psychosocial factors.

4.

Depression is associated with poorer will to live and greater desire for a hastened death (

89,

90). Together with extrapolations from data regarding functioning in a variety of medical populations (

91,

92), these data strongly suggest that depression is associated with excess functional morbidity and poorer quality of life in dying patients, making it an important target for palliative care.

5.

Better treatment of chronic pain or other physical symptoms may result in improvement in concomitant depressive symptoms. Conversely, successful treatment of depression may reduce patient ratings of pain severity or pain-associated functional morbidity (

93).

6.

Turning to depression treatments, to my knowledge there are no well-controlled trials of drugs or psychosocial treatments in terminally ill patients. Extrapolating from literature in chronically medically ill patients, depression in dying patients probably can respond to standard treatments (

91,

94), with resultant improvement in “quality of life” such as subjective distress and functional morbidity, although response rates may be lower than that seen in healthier populations. In the absence of further empirical data, choice of antidepressant drug should be guided by side-effect profile in the context of the patient’s symptoms and comorbidities. Also, there may be a role for psycho-stimulants in targeting anergia, anhedonia, and abulia in patients who do not have a full major depressive syndrome, or in depressed patients with a very short life expectancy, in whom rapid symptomatic improvement is needed (

95–

99). Recently, the newer stimulant modafinil has been used (

100), although it is not yet clear whether its putatively better side-effect profile, compared with older agents such as methylphenidate (on the basis of its brain regional selectivity) results in better efficacy due to greater tolerability of higher doses.

Suicidal ideation. The tenets of clinical suicidology as applied to older persons in general are of great relevance to dying patients (

101), providing a crucial area for the expertise of the geriatric psychiatrist. Wishes or requests for hastened death, and attempted and completed suicide, are common in cancer patients (

102,

103), and likely in other terminal populations, as well. Issues relevant to assisted suicide and euthanasia are discussed below. The above-noted concerns about distentangling “normal” hopelessness and worthlessness from pathological processes in those facing imminent death may complicate the clinical assessment of suicidality, and are problematic when attempting to determine prevalence rates and risk factors. Nonetheless, persistent wishes to die, and certainly specific suicidal ideation or plans, warrant careful clinical evaluation for modifiable contributing factors, which in terminal patients are likely to include depressive disorder, pain, agitation/distress as part of delirium or dementia, or social isolation (

13).

Anxiety. Although empirical prevalence data are relatively lacking, it is well recognized that anxiety is a common and distressing symptom in dying patients (

13,

14,

104). Anxiety may be comorbid with depression or delirium, or it may present alone as a primary condition or as secondary to medical illness or its treatments. Affective, ideational, or physiological manifestations of anxiety commonly accompany distressing physical symptoms such as pain, dyspnea, and vertigo. Anxiety in dying patients often occurs in a generalized anxiety pattern, although panic attacks or acute stress disorder-like symptoms (referable to the medical disease, its treatments, or to a feared mode of death) may be seen. Anxiety may contribute, along with depression, to a desire for a hastened death (

105). Geriatric psychiatrists will draw on their expertise in assessing anxiety in the context of such comorbidities.

Recommendations for treatment of anxiety are based largely on extrapolations from other populations, given that controlled trials in terminally ill patients are lacking. If rapid symptom control is needed because of acute distress or limited remaining life-span, benzodiazepines or (in the presence of delirium or significant dementia) antipsychotic medications are the treatments of choice, sometimes in combination with opioids or other sedatives (see below). Opioids may be particularly useful for anxiety in the context of dyspnea due to cardiac or pulmonary disease (

106,

107). If time available permits, antidepressant medications may be the primary treatment for generalized anxiety or panic-pattern symptoms (whether or not they are judged to be secondary to medical illness), or if the anxiety is comorbid with significant depressive symptoms. The role of other agents, such as buspirone, in treating anxiety in dying patients has not been well defined. Similarly, cognitive-behavioral or supportive therapy for anxiety may be useful in patients who have sufficient time, cognitive capacity, and motivation for treatment, although, again, empirical studies in terminal patients are few and are not well controlled (

108,

109).

Delirium. Unsurprisingly, dying patients commonly develop “acute brain failure;” that is, the fluctuating global cognitive dysfunction of delirium related to primary CNS disease or to the CNS sequelae of systemic diseases or medications (

110,

111). Although cognitive impairment is the hallmark of the delirium syndrome, it is important to remember that other portions of the mental status examination may be prominently affected, for example, depression, anxiety, psychosis, or psychomotor disturbances. Often the manifestations of delirium considerably add to the patient’s morbidity and to distress for the family. The standard approach to delirum evaluation, namely to identify and treat the underlying causes, may not always apply to dying patients. The causes may not be remediable, or may be iatrogenic in the service of palliation, for example, opioids or glucocorticoids. In many cases, work-up to determine the underlying cause(s) will be precluded by patient/family decisions to pursue a purely palliative approach. In any case, one should re-evaluate the benefit/risk profile of all CNS-active medications, balancing the helpful effects of such drugs with their potential contribution to the state of delirium. Symptomatic management often targets distressing components of delirium, such as agitation, psychosis, or affective lability. Although there may be some role for simple environmental interventions (i.e., decreasing unnecessary stimuli when possible), the mainstay of therapy for these symptoms remains antipsychotic medications. The second-generation antipsychotic medications have been used, but their advantage (presumably in terms of side-effect profile) over older antipsychotic drugs in terminal (or indeed any) delirium is not yet clear (

112). For intractable terminal delirium that produces severe or dangerous agitation or distress, other agents may be used alone or in combination with antipsychotics, including benzodiazepines, opioids, or anesthetic agents (see the section below on terminal sedation).

The geriatric psychiatrist is well versed in the assessment and management of delirium in the medically ill older patient. She or he also can serve a useful educational role for the family and sometimes for other medical providers, informing them about the cause of the distressing symptoms (e.g., that the emotional symptoms in delirium do not have a purely “psychological” origin and may not respond well to interpersonal interactions alone), and helping avoid the unnecessary and often counterproductive use of other psychotropic medications (e.g., hypnotics or antidepressants).

Role of supportive psychotherapy. In addition to the psychiatric disorder-specific indications for focused psychotherapies, other forms of time-limited psychotherapy may be quite useful for selected patients or their families (

108,

109). Geriatric mental health specialists can draw on their knowledge of individual and family developmental issues as related to later life, as well as their specific psychotherapeutic skills. Particularly if contacts are begun earlier in the trajectory of an ultimately life-ending illness, individual psychotherapy may be used to facilitate life review, to help the patient set, prioritize, and achieve manageable goals in the time they have remaining, and, in some cases, to process longer-standing unresolved conflicts or dysfunctional patterns of thinking or interactions that affect the dying process. Some patients may come to view dying as an opportunity for psychological or spiritual growth, a possibility that physicians should suggest and support when possible (

113).

Family dynamics, of course, are a clinically crucial context within which the dying process takes place, and may be quite prominent in their effects on the treatment alliance and on needed decision-making. As with the individual, clinicians should assess the family to inform an approach that capitalizes on the family’s strengths and shores up areas of weakness (

30). The mnemonic “L-I-F-E” has been suggested to organize approaches to brief family assessment, including

Life-cycle stresses,

Individual roles within the family,

Family relational processes, and

Ethnic factors (

114). Depending on the family’s needs, interventions may range from education and community referral to deeper interventions, such as restoring effective problem-solving, improving patterns of communication, or improving attachment and caregiving bonds (

115). Family contacts also may be viewed as preventative: education and support may aid the grieving process even before the patient dies, optimally reducing the likelihood that bereavement will be complicated by depression or traumatic grief (

116), and increasing the likelihood or rapidity with which family members seek treatment for complicated bereavement.

Other clinical issues

Capacity. Given the high prevalence of delirium or dementia in terminally ill patients, along with the prevalences of other conditions affecting the physical ability to communicate, it is not surprising that many dying patients at some point are not able to fully participate in making informed decisions about their care. Geriatric or consultation psychiatrists are often consulted when capacity determination is complex or difficult; for example, when subtle cognitive difficulties produce a state of “partial capacity,” or when it is difficult to determine whether a depressive disorder is present (i.e., to distinguish this from “normal” in the context of severe physical illness) and whether such a depressive disorder is clouding capacity. As always, determination of capacity applies only to the current clinical state; capacity often changes as the patient’s mental state improves or worsens over time. Also, capacity determination should be applied to a particular decision or action to be made; thus, for example, one assesses that a patient does not demonstrate capacity at the present time to make an informed decision about

X (specific medical intervention). To demonstrate capacity, patients should show the four key components of capacity (

117,

118): based on an

understanding of the facts of their condition and the options before them, and

appreciation of the significance of these facts; the patient must convey an

expressed choice based on

reasoned consideration of the situation in a manner consistent with his or her personal and cultural preferences and values. Many have argued for a “sliding-scale” approach to capacity determinations (

117,

119,

120), that is, that the least-stringent capacity standard should be applied to those medical decisions that are of low danger and that are most clearly in the patient’s best interest, whereas the most stringent standard of capacity should be applied to those decisions that are “very dangerous and fly in the face of both professional and public rationality” (

119). Because of this, geriatric psychiatrists are also more likely to be consulted for capacity determination when the implications of a capacity determination are particularly profound (e.g., decisions about initiating or discontinuing life-sustaining treatment).

It also should be noted that consultations for capacity determination often are requested in the context of complex issues with the patient, the family, or the negotiation of an appropriate treatment plan. The geriatric psychiatrist should be mindful of such broader issues; while being sensitive to the boundaries of the consultee’s initial request, the so-called “competency consult” may lead to additional opportunities to be of help to the patient, family, or treatment team.

Advance care planning. Given that, at some point, many dying patients will lose the capacity to participate in decisions about their care, it is highly desirable that patients express their preferences in advance while they are able to do so. Patients may specify their wishes about future medical care in broad, general terms, or may specifically request that particular interventions be used or not used in their care. Mechanisms for doing so include specific physician’s orders at the request of the patient (e.g., “Do Not Resuscitate” or “Do Not Intubate” orders), living wills (i.e., documents in which the patient requests or forbids specific interventions in advance), the verbal expression of care preferences to family or providers, or the appointment of a healthcare proxy or equivalent, such as durable medical power of attorney. Physicians should broach the topic of advance care directives with their patients relatively early in their illness’ trajectory, as there is evidence that doing so increases the likelihood that a patient’s wishes will be followed, avoiding unwanted interventions or the preservation of life in a condition that the patient had previously deemed not worth sustaining (

19,

23). Because of the heterogeneity of patients’ general values about death and dying and the difficulty in translating such values into specific healthcare preferences, attempts to elicit preferences from patients should include inquiries about specific healthcare choices as much as possible (

121). Even so, advance statements of healthcare preferences cannot take into account the myriad variables that might affect assessment of the desirability of a particular option or life state. Thus, advance statements about who should speak on the patient’s behalf should capacity be lost—that is, a healthcare proxy or equivalent—are the most flexible and useful. Geriatric psychiatrists working with patients with potentially life-threatening illnesses should encourage their patients to have such discussions with their primary care provider or relevant specialist, and, for some patients and families, may play a facilitative role in helping the patient think through the available options in the context of their values.

Withholding or stopping life-sustaining treatments. Most patients and families facing death from terminal illness at some point will be faced with a decision as to whether to begin treatments such as mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or artificial administration of fluids and food, or whether to discontinue such treatments after they have begun. As already noted, these concerns often are incorporated in the content of advance directives. Physicians can help the decision-making by providing frank assessments of the likelihood that these interventions will lead to meaningful recovery, and whether interventions such as ventilation will be short-lived or indefinite. Patient and family decisions can then weigh these facts in the context of how they define “quality of life” or dignity. Sometimes religious or cultural values require the individual to accept all possible life-sustaining treatments. It must be recognized that, although most experts believe there is no ethical distinction between stopping and not initiating a treatment, for the persons directly involved, stopping treatment often feels like “pulling the switch” or otherwise “causing” the patient’s death (

122). Physicians can helpfully reframe such decisions as allowing the disease to take its natural course toward death, and as not continuing treatments that merely prolong suffering. In so doing, one must be clear about one’s own goals in providing or framing information. We must use our best judgment, based on assessment of the clinical situation, the needs of the patient and family, and relevant ethical considerations, to decide in each case what is the best proportion of “neutral” information-sharing versus purposeful shaping of information and language to achieve particular ends (such as guiding a family to make a specific decision, or easing their suffering in the decision-making process).

The withholding of artificial hydration and nutrition often contributes to a more comfortable death with gradual loss of consciousness, particularly with assertive supportive care (e.g., oral care) (

123). Also, there is a lack of evidence that tube-feeding lengthens or improves life in terminally ill patients (

124–

126). Education about these issues is essential, because many patients and families expect that “starving to death” is an uncomfortable process. In most states in the U.S., discontinuation of life-sustaining treatments, including artificial hydration and nutrition, is viewed like any other medical treatment, and usual guidelines about the use of advance directives or substituted judgment of a healthcare proxy apply (

127). However, some states have explicit legislation regarding specific interventions. For example, in New York, decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatment in a patient currently lacking capacity to make this decision must include some evidence that this decision is consistent with the patient’s specific previously expressed wishes.

Terminal sedation. Although proper palliative care, in most cases, can eliminate physical suffering or reduce it to tolerable levels, there are some patients for whom our best efforts cannot produce an acceptable quality of life (

122). Fear of such suffering may be part of what drives requests for assisted suicide or euthanasia (see next section). An approach acceptable to many clinicians, patients, and families, even those for whom assisted suicide is not viewed as acceptable, is the use of terminal sedation; that is, the use of medications to produce an unconscious state in which the patient ultimately dies from the underlying disease (

128–

130). Several classes of medications may be used for this purpose, most commonly including benzodiazepines (e.g., continuously infused midazaolam), opioids, and anesthetics such as propofol. To state the obvious, terminal sedation should be used as an option of last resort, after careful consideration with the patient and family. For many patients, however, preparatory education about the availability of terminal sedation substantially allays fears of suffering or physician abandonment in the final days of life. Thus, terminal sedation should be mentioned as an option far more frequently, and earlier in the illness course, than it is actually used.

Geriatric psychiatrists can play important roles regarding decisions to withhold life-sustaining treatments or to initiate terminal sedation. These may include clarifying the patient’s or family’s values (including the effects of religious beliefs on perceptions of these options, and negotiation when disagreements within the family make it difficult to achieve consensus), and providing expert opinions about psychiatric symptoms’ coloration of the patient’s decision-making and the likelihood that such symptoms can be reversed or ameliorated.

Physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is defined as a person killing him- or herself by using medications or a device provided by a physician for that explicit purpose. Euthanasia is defined as the physician-ordered intentional killing of a patient, typically by a lethal dose of a medication administered by the physician or designee, such as a nurse. Most clinicians and ethicists agree that both are to be distinguished from the death of a terminally ill patient that is hastened by the side effects of opioids or other medications used to control pain or suffering, where the explicit goal is to reduce suffering rather than to cause death; this distinction is known as the “doctrine of double effect” (

2,

131,

132) and is increasingly recognized by the legal system as a legitimate component of proper palliative care (

127), although some have questioned the validity of this distinction, grounded as it is on the complex and often ambiguous concept of intentionality (

133).

The public and professional debate about the desirability of PAS or euthanasia has been highly visible and often hotly contested. A variety of clinical, ethical, religious, and legal arguments have been mounted both in favor of and against legalizing such practices, as discussed elsewhere (

134,

135). Descriptions of these practices, for example, euthanasia in the Netherlands, or PAS in Oregon, often offer differing interpretations of the available data, depending on the observer’s bias (

134,

136–

140). At this time, euthanasia is illegal throughout the United States. Oregon has legally sanctioned PAS in terminally ill patients after meeting certain prerequisites intended to prevent abuses such as the use of PAS to cause death from suicidal depression. Clinicians, including thoughtful proponents of PAS, recognize that proper evaluation of requests for PAS may lead to a range of appropriate responses, including the use of reassuring assertions of the tenet of physician non-abandonment, or by identification and treatment of remediable suffering from pain, depression, or other symptoms (

141–

143). As with many areas of palliative care, there is much empirical research needed that could inform the ongoing debate about the proper clinical and legal paths to take, and geriatric psychiatrists’ expertise is well suited to address crucial unanswered questions (

144).