Treatment plans should include assessment and treatment of several problem sets: physiological impairments; behaviors that maintain eating disorders, such as restrictive eating, excessive exercise, binge eating, and purging; self-endangering attitudes, thoughts, and emotions that sustain the disorders; and co-occurring psychiatric disorders (

20). In treating anorexia nervosa especially, key initial tasks may include enhancing the patient’s motivation, involving the patient in treatment despite his or her ambivalence, and engaging the family’s assistance in conducting treatment. Although motivational interviewing techniques used in substance use disorders are being examined for their potential utility in increasing readiness for change among patients with eating disorders, the effectiveness of such techniques remains to be demonstrated (

21).

The extent of the initial medical workup depends on the patient’s degree of nutritional impairment. Along with the usual metabolic measures, such as CBC, electrolytes, magnesium, calcium, liver function tests, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone, current recommendations sometimes include complement factor 3, a sensitive measure known to indicate malnutrition even when other parameters are normal (

22). For thin patients, an electrocardiogram is recommended, and for those showing any cardiovascular signs or symptoms, a cardiac ultrasound may be considered (

23). A bone density scan is recommended because osteopenia may occur within a year after onset of amenorrhea (

24). Demonstrating early osteopenia may help motivate wavering patients. Psychological assessment should include family members whenever feasible.

Treating anorexia nervosa

Although few controlled clinical trials have been conducted (

20,

25), numerous observational studies suggest that initial treatment should focus on refeeding (

20,

26,

27). Ambulatory treatment usually requires an interdisciplinary team that includes a general physician and a registered dietician who will monitor weight and laboratory indicators if the psychiatrist does not routinely perform these functions. Initial caloric intake should be tolerable to the patient but increased every few days to ensure a weight gain of 1–2 pounds per week (

20). Controlled studies show that family involvement in treatment improves outcomes for younger patients, except when highly dysfunctional family patterns preclude such involvement (

28,

29).

The decision about when to hospitalize a patient with anorexia nervosa depends on specific physiological and psychiatric status, patient and family motivation and ability to adhere to weight-gain programs, and personal and local resources. Indications for hospitalization and other settings of care are detailed in APA’s

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders (

20). Especially for patients whose initial weight is 25% or more below expected weight but also for patients at higher weight levels, depending on a comprehensive assessment of psychiatric and medical circumstances, hospitalization is often necessary to ensure adequate intake and to limit physical activity. In younger children and adolescents, hospitalization should be considered even earlier if the patient is losing weight rapidly, before too much weight is lost, since early intervention may avert rapid physiological decline and loss of cortical white and gray matter (

20). Generally, specialized eating disorders units yield better outcomes than general psychiatric units because of nursing expertise and effectively conducted protocols (

30). One study suggested that short-term outcomes for involuntarily hospitalized patients are similar to those for voluntarily admitted patients (

31). Higher rates of relapse and rehospitalization have been shown to occur when patients are prematurely discharged from inpatient care (

32). Since weight gains of more than 2–4 pounds per week may be physiologically unsafe, patients who need to gain 20–30 pounds to restore health may require 2–3 months of hospital treatment. Partial hospitalization programs have been found to be effective in direct relation to their intensity: 8-hour, 5-day-a-week programs may approach inpatient programs in effectiveness, whereas programs that involve fewer hours and/or fewer days per week are much less effective (

33,

34). In fact, however, few partial hospitalization programs specialized for treatment of eating disorders exist.

For acutely thin patients with anorexia nervosa, there have been few controlled medication studies to guide treatment. For patients treated in well-implemented inpatient programs, adding a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) provides no advantage for weight gain or reduction of hospital stay (

35,

36). Several small open-label studies (

37–

39), the largest of which involved 20 patients, and one small controlled trial comparing olanzapine and low-dose chlorpromazine (

40) suggest that low doses of atypical antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine (2.5 to 15 mg/day) may improve weight gain and psychological indicators, but good controlled studies are lacking. With regard to psychotherapy, a recent small controlled study suggests that although dropout rates were substantial for all treatments, for acutely ill patients neither cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) nor interpersonal psychotherapy was superior to a well-conducted manualized nonspecific supportive clinical management based on empathic care, nutritional education, and advice (

41).

In dealing with the osteopenia and osteoporosis resulting from anorexia nervosa, the only intervention shown to potentially reverse bone loss is nutritional rehabilitation during the period of bone growth, ensuring sufficient dietary protein, carbohydrates, fats, calcium, and vitamin D (

42). Supplemental estrogen-progestins (

43), calcium, and/or vitamin D have not been shown to meaningfully reverse skeletal deterioration but are often prescribed in routine practice. Interventions for bone revitalization using recombinant human insulin-like growth factors (IGF) (

44) and biphosphonates (

24,

45) are being investigated but cannot be recommended for routine clinical use.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, severe mood disorders, and/or substance dependence, require modifications of psychiatric medications and psychotherapies.

A controlled trial has shown that after sufficient weight restoration has occurred to permit return to ambulatory aftercare, fluoxetine, averaging 40 mg/day, may help avert subsequent weight loss, depression, and rehospitalization (

46). Another controlled study demonstrated that although dropout rates were high, CBT after weight gain may reduce relapse (

47). In controlled trials with adult patients, other psychotherapies, including focal psychoanalytic and family therapy, have proved better than low-contact treatment (

48). For younger patients, family involvement is always required, and family therapy clearly shows advantage for patients 18 years of age or younger (

49). Recovery is often prolonged even in the best of situations. Full psychosocial recovery may take 5–7 years, with treatment continuing long after weight is restored (

50,

51).

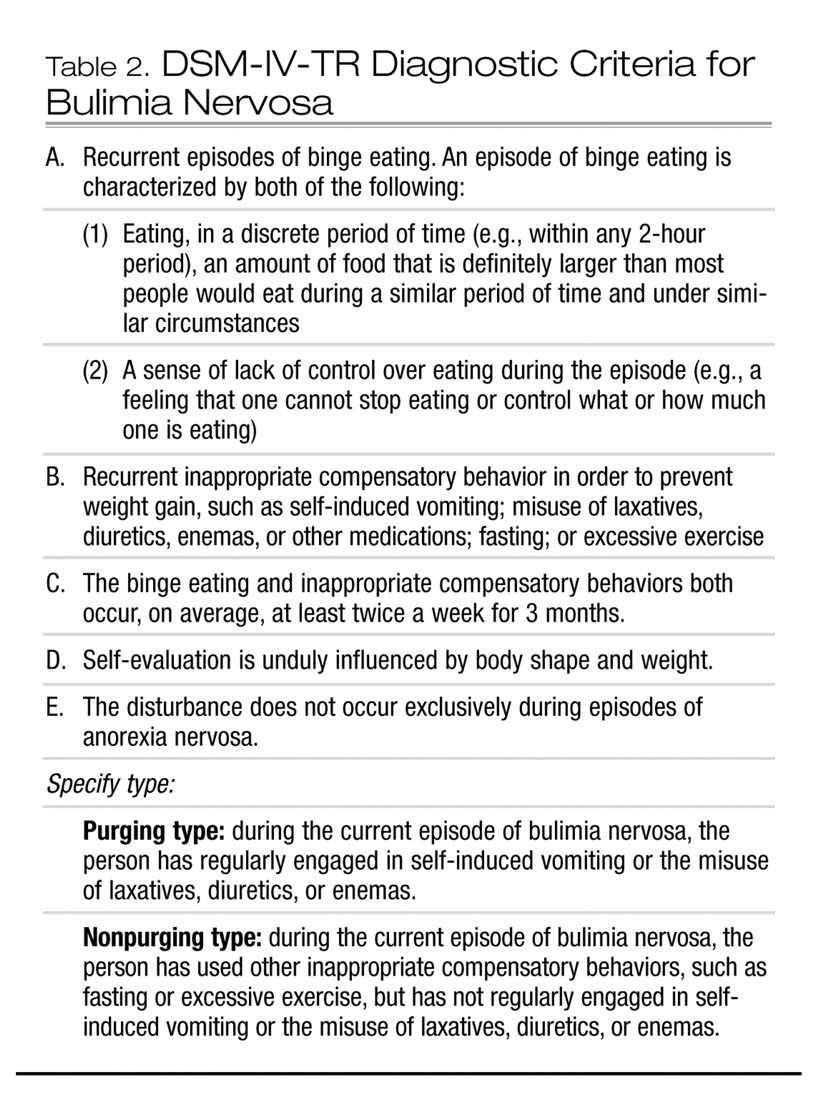

Treating bulimia nervosa

Both psychotherapeutic and medication treatments are available for treating bulimia nervosa, and some studies suggest that combining CBT and an SSRI yields the best results (

52). Available evidence supports CBT-based treatments as the most effective single approach (

53,

54), but many psychiatrists are not well trained in this area. Controlled studies show that both individual and group CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy are effective in treating bulimia nervosa (

55), and dialectical behavior therapy focusing on emotion regulation skills has been shown to result in significant improvement in binging and purging behavior compared with waiting-list control subjects (

56). CBT either alone or in combination with nutritional therapy was more effective than nutritional therapy alone or a control support group (

57). In cases where clinical complexity does not immediately mandate more intensive interventions, self-management strategies employing written, Web-based, or CD-ROM-based CBT-oriented manuals (

58–

63) may effectively help some patients with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. However, limitations are evident; many patients do not complete these trials (

64), and many who do complete them ultimately seek professional treatment (

58). Adding fluoxetine to self-help manual-based interventions may yield better outcomes than either treatment alone (

65).

Among patients who failed an initial course of CBT, a small controlled study showed that those who were subsequently assigned to a fluoxetine group did better than those who received placebo (

66). However, high dropout and low abstinence rates have been seen among patients who underwent a trial of interpersonal psychotherapy or medication management after failing CBT (

67). For relapse prevention, scheduling regular visits is recommended, since simply telling successfully treated patients with bulimia nervosa to come back if they have additional problems appears ineffective as a relapse prevention technique (

68).

Various medications have been used in treating bulimia nervosa. SSRIs have long been considered the gold standard, particularly fluoxetine, for which the largest controlled studies have been conducted (

69). With fluoxetine, the higher dose levels usually used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorders (typically 60 mg) are more effective than the lower doses usually effective for depression (typically 20 mg). Early smaller series showed effectiveness for tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, which are now rarely used. These medications are no longer recommended as first-line treatments. Other classes of agents have been investigated, largely in relatively small industry-sponsored studies. In double-blind studies, inositol (which has also been effective in treating depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder) (

70), ondansetron (

71), and topiramate (

72,

73), and, in open trials, the selective noradrenergic receptor inhibitor (SNRI) reboxetine (not available in the United States) (

74,

75) have all been reported to be effective in treating bulimia nervosa.

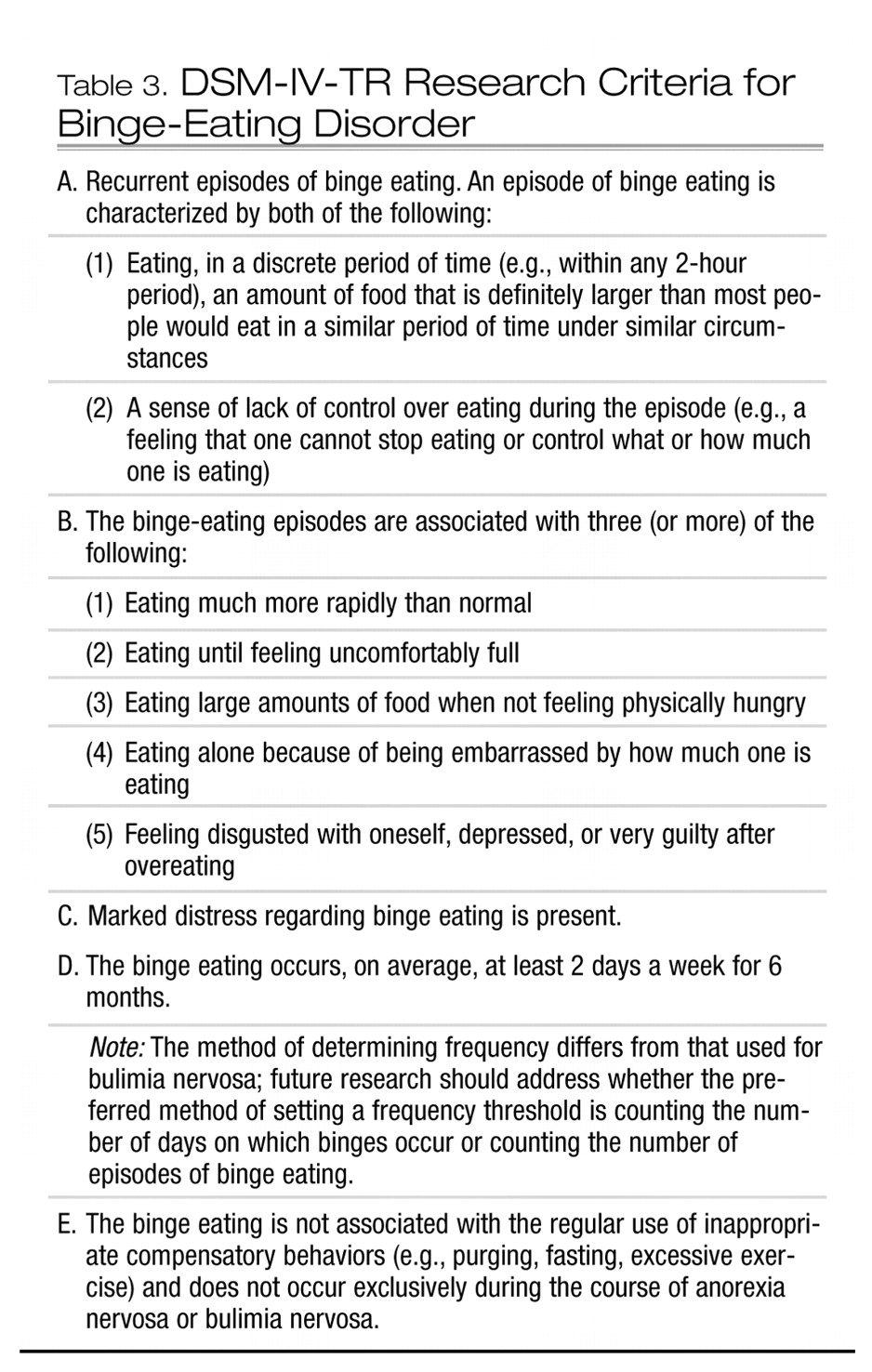

Treating eating disorder not otherwise specified

Within this heterogeneous category, binge-eating disorder merits particular attention. Interpreting treatment studies of binge-eating disorder requires caution, since the symptoms of this disorder are often labile, and high placebo response rates are frequently seen.

CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy have been studied most extensively in binge-eating disorder, and both appear to do reasonably well at keeping patients in treatment. Results of psychosocial treatments resemble those for bulimia nervosa (

76). Treatment of binge-eating disorder often entails concurrent interventions to address comorbid obesity, usually involving behaviors, exercise, and diet. Some research shows that patients with binge-eating disorder who receive CBT do better if they also receive exercise instruction monitored by and subsequently maintained with biweekly booster sessions conducted by exercise staff (

77).

Results of medication studies for binge-eating disorder also parallel those for bulimia nervosa. More recent studies, most of them industry funded, have shown several SSRIs to be somewhat effective. In 6-week double-blind placebo-controlled trials, fluoxetine (

78) and citalopram (

79) have each been shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing binge-eating behavior and promoting weight loss. In another small study, fluvoxamine was not more effective than placebo, although improvement was seen with both (

80). In a 12-week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the SNRI sibutramine was superior to placebo in reducing binge eating, with differential results evident by the third week (

81). Several novel anticonvulsants, including topiramate (

82) and zonisamide (

83), have also shown promise for binge-eating disorder in recent trials, but about 25% of patients in these studies discontinued the anticonvulsant because of adverse events.

Overall, the available evidence seems to favor psychotherapy alone over medications alone for treatment of binge-eating disorder. In a recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the addition of 60 mg/day of fluoxetine to CBT did not appear to alter rates of remission or produce substantial advantage on dimensional measures of binge eating or psychological distress (

84). In some other instances, adding medications to CBT-based psychotherapy has appeared to enhance the effects of CBT on eating behavior or at least on symptoms of depression (

85).