It has been reported that the increasing prevalence and dispersion of obesity in the general population are commensurate with those of a communicable disease epidemic (

1). Several subpopulations of psychiatric patients (e.g., those with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder) have an increased risk of overweight and obesity (

2). Moreover, in many psychiatric patients risk factors tend to cluster for type 2 diabetes mellitus and other general medical disorders (

3). Mortality due to a general medical condition is the most frequent cause of excess death among persons with mood and psychotic disorders (

4,

5). Obesity is a well-established risk factor for many medical disorders that are differentially reported in psychiatric populations (

6). Mental health care providers must be familiar with the definitions, measurements, psychiatric and medical consequences, and management strategies for obesity. Many psychiatric medications are associated with clinically significant weight gain and metabolic disturbances (

2,

7). To address these issues, we review 10 questions on obesity and mental disorders that are frequently asked by mental health care providers.

To formulate answers to 10 commonly asked questions about obesity and mental health, we conducted a MEDLINE search of all English-language articles published between 1966 and June 2005. The search terms were obesity, overweight, body mass index (BMI), metabolism, bariatric treatment, weight-loss treatment, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, binge-eating disorder, eating disorder, and psychotropic medication. The psychiatric disorders were cross-listed with obesity, overweight, body mass index, bariatric treatment, and metabolism. The search was supplemented with a manual review of relevant references. In the following, “excess weight” refers to both overweight and obesity, and use of the word significant denotes statistical significance at an alpha level of 0.05 or less.

Ten frequently asked questions on obesity

1. How is obesity defined and operationalized?

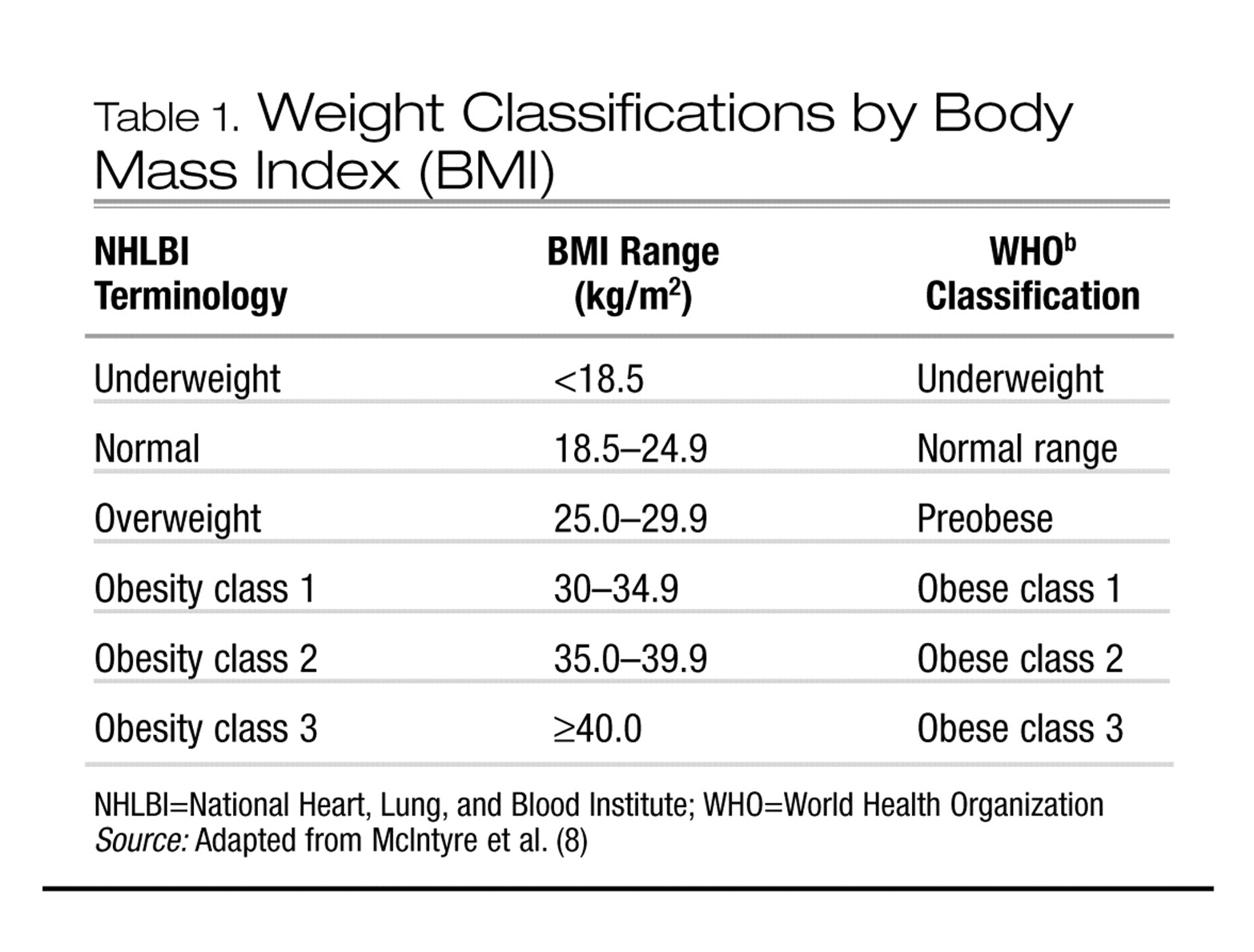

Normal body weight is defined as a body mass index (BMI) in the range of 18.5–24.9; BMI is computed as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Overweight, sometimes referred to as “pre-obese,” is defined as a BMI in the range of 25–29.9. A BMI of ≥ 30.0 is defined as obesity. Obesity has also been divided into subclasses (Table 1). Overweight in children and adolescents is frequently defined as a BMI in the 95th percentile or higher for age and sex (

9).

The most frequently cited anthropometrics are weight, BMI, waist-to-hip girth ratio (WHR), and waist circumference. Total body weight and/or increase in absolute weight are the most frequently cited markers of excess weight. BMI, which takes height and weight into account, is a more useful metric. The WHR provides an estimate of the abdominal accumulation of body fat. Undesirable accumulation of body fat is defined as a WHR greater than 0.9 for males and 0.8 for females. It has been proposed that a WHR in excess of 0.85 in women and 1.00 in men is associated with alterations in glucose-insulin homeostasis and lipid-lipoprotein metabolism. The WHR is obtained by measuring the waist between the iliac crests and the lower costal margin and dividing that measure by the maximum circumference around the buttocks. It has been reported that waist circumference alone provides an adequate proxy of visceral adipose tissue. Obesity-associated morbidity is reported to be higher when the waist circumference exceeds 88 cm in females and 102 cm in males (

10).

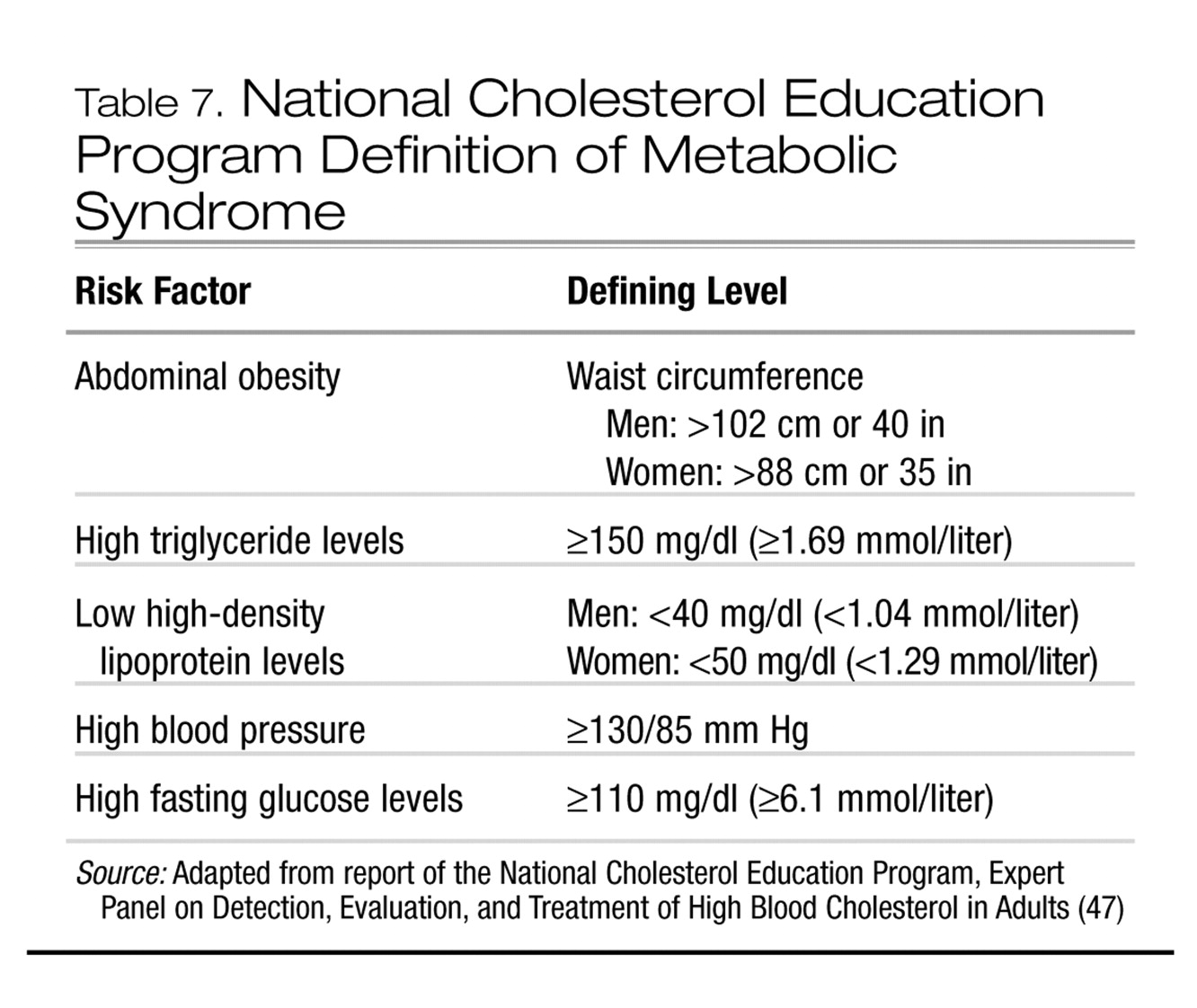

Straker and colleagues (

11) evaluated the clinical utility and cost-effectiveness of screening for the metabolic syndrome (see question 7) in a heterogeneous group of psychiatric patients who were treated with a variety of atypical antipsychotic agents. The overall prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was 29.2%. Abdominal obesity and elevated fasting blood glucose (>110 mg/dl) identified 100% of patients with the metabolic syndrome. These data indicate that combining measurements of waist circumference and fasting blood glucose is a reasonable and cost-effective proxy of metabolic syndrome in this patient group.

2. What is the prevalence of excess weight in the general population?

Obesity is the most common nutritional disorder in North America and globally (

12). It is estimated that up to 54% of the adult population in the United States is overweight and approximately 30% are categorically obese (

12–

15). The estimated prevalence of obesity has been increasing significantly over the past two decades. For example, data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1998–1994) indicate that the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 30.5% in the 1999–2000 survey, compared with an estimate of 22.9% in the 1988–1994 survey. The prevalence of overweight also increased during this period, from 55.9% to 64.5% (

14). The estimated prevalence of excess weight in pediatric populations has also more than doubled over the past three decades (

16).

3. Which psychiatric populations are at risk for obesity?

Major depressive disorder, binge-eating disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia are associated with excess weight (

2,

3). A comprehensive review of the association between depression, binge-eating disorder, and obesity has been reported elsewhere (

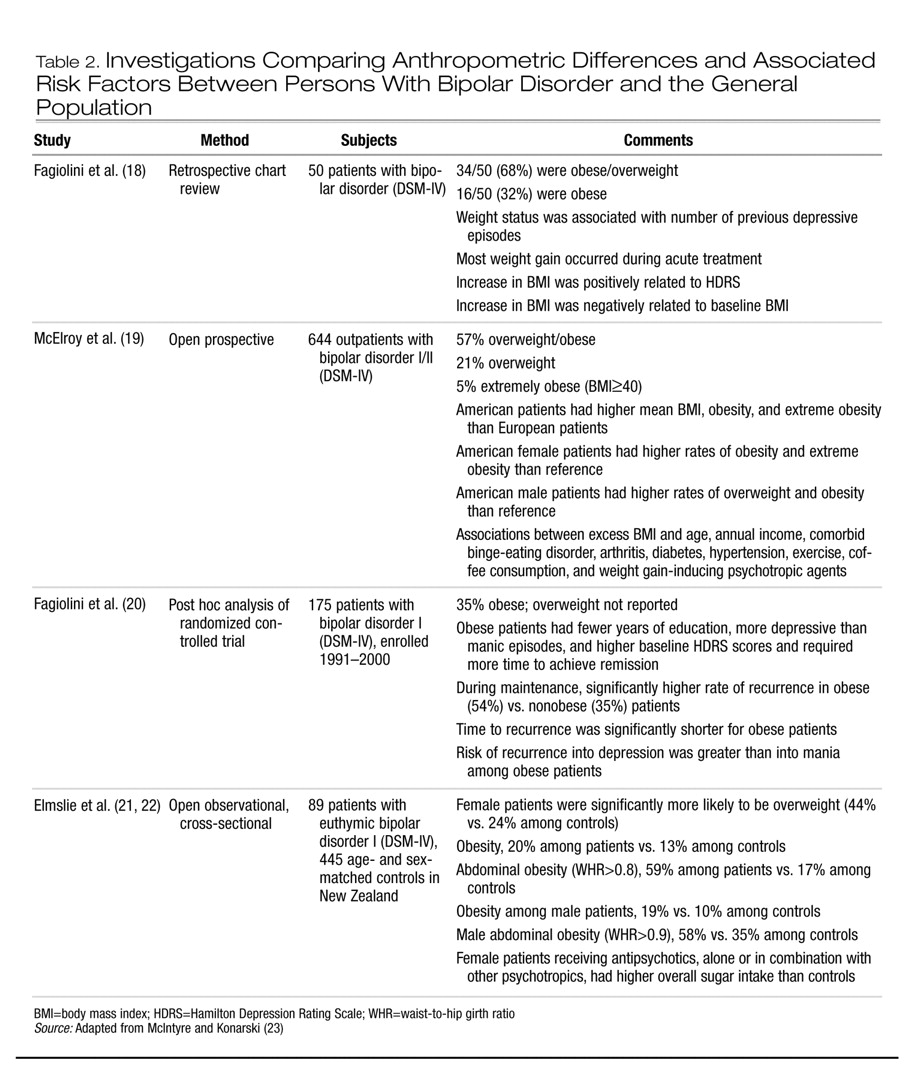

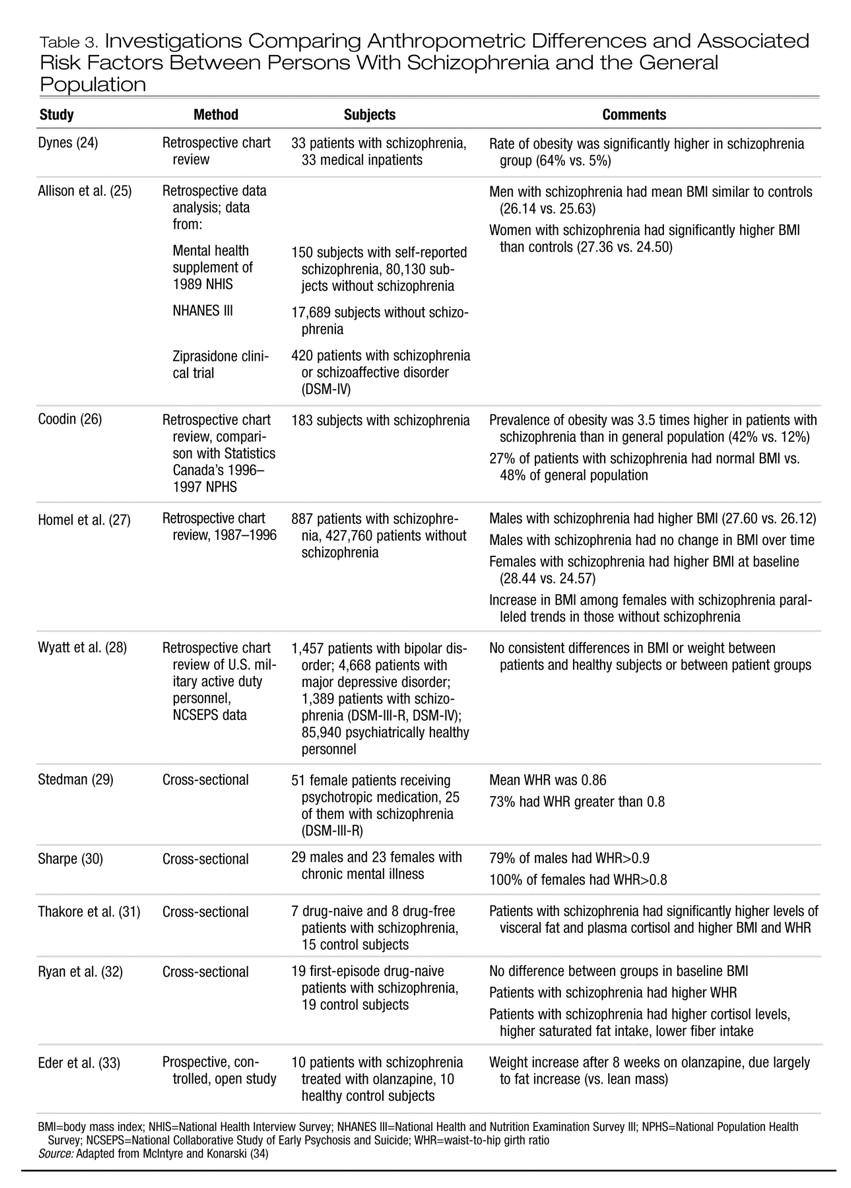

17). In Tables 2 and 3 we summarize data on obesity in patients with bipolar disorder and with schizophrenia. Taken together, contemporary studies indicate that persons with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be obese. Moreover, the WHR in both patient groups may also be higher than in the general population, indicating an abdominal distribution of excess weight.

4. What are the risk factors for obesity in psychiatric patients?

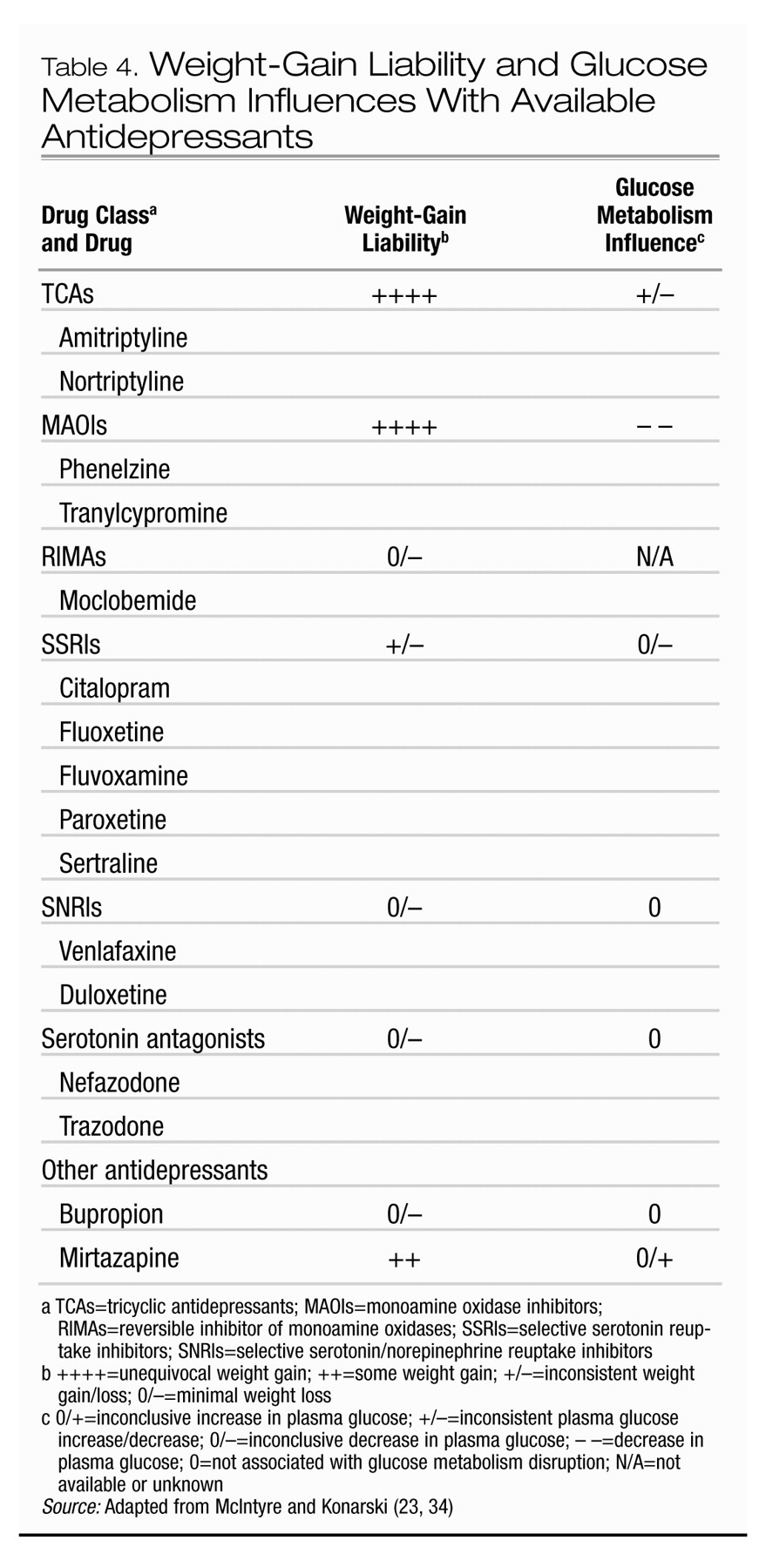

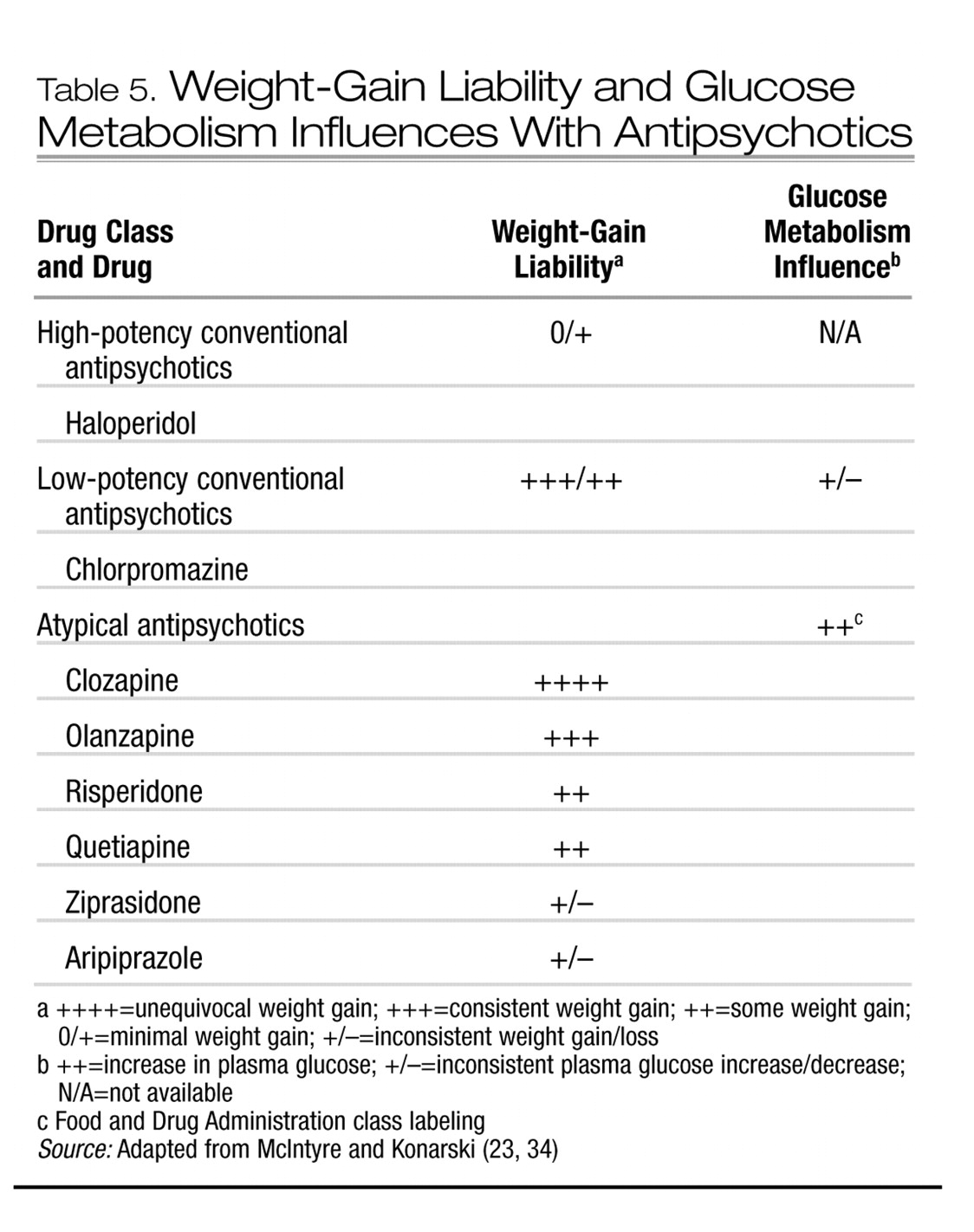

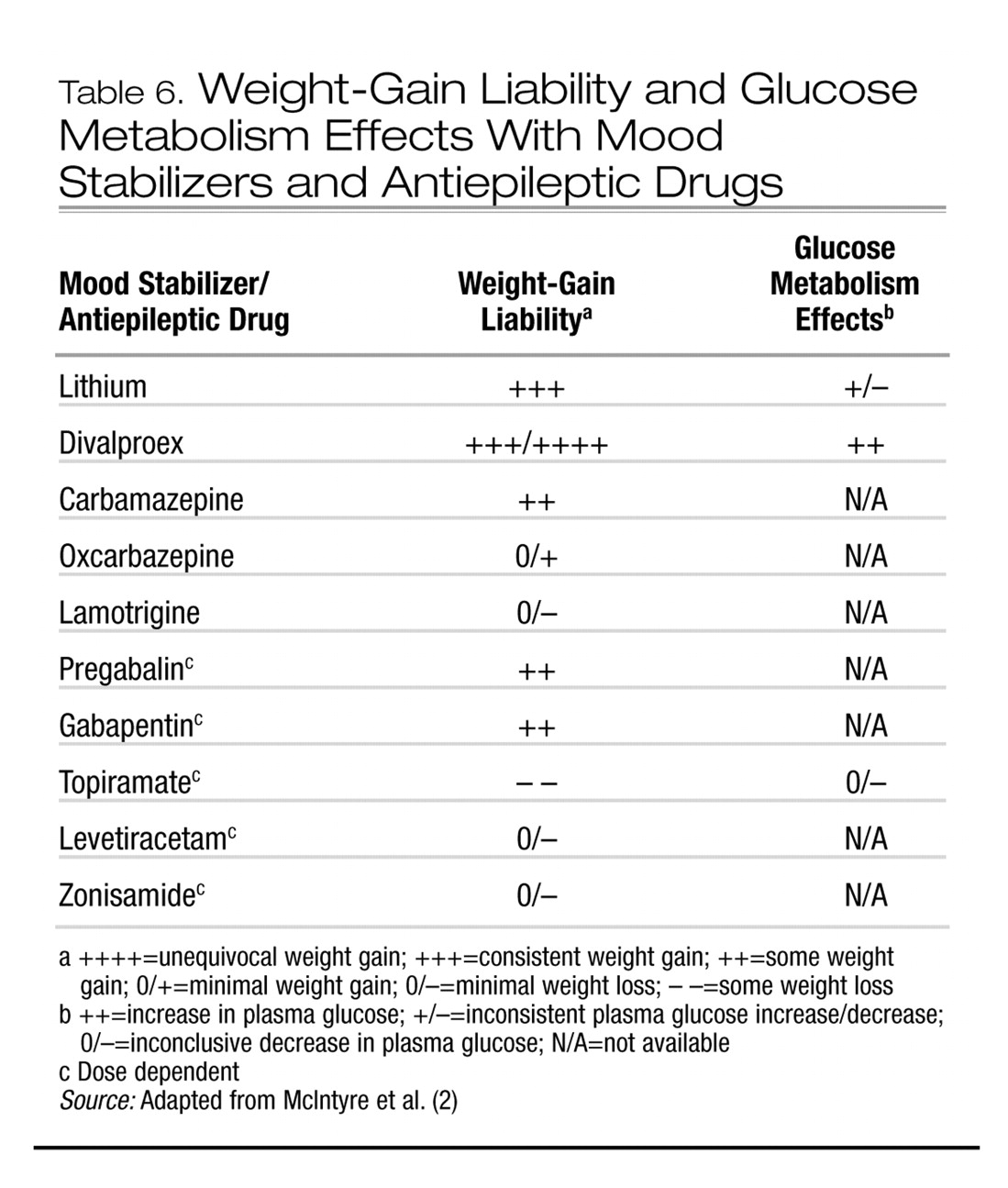

Risk factors for obesity tend to cluster in patients with psychiatric disorders, including insufficient access to primary and preventative health care, poverty, and others (

3). Several psychotropic medications are particularly associated with clinically significant weight gain (Tables 4–6). The association between atypical antipsychotics and weight gain has been comprehensively examined (

3). Several correlates of weight gain in patients taking antipsychotics have been suggested, although few are compelling. Younger age, improvement in psychopathology, and lower basal BMI have been the most consistently reported variables associated with antipsychotic-associated weight gain.

5. What are the mechanisms of weight gain in patients taking antipsychotic medications?

The balance between energy intake and expenditure largely determines net body weight (

35). Energy expenditure can be further partitioned into resting energy expenditure and activity-related expenditure (

36). Weight gain is a highly complex multifactorial phenotype with a heritability liability of approximately 70% (

37). Energy intake and expenditure are tightly regulated by a panoply of central and peripheral energy homeostasis mechanisms. It is likely that antipsychotic-associated weight gain is promoted by several mechanisms, with an increase in appetite via an affinity for central appetite-stimulating systems occupying a central role (

38,

39).

6. What are the medical and psychiatric consequences of obesity?

The medical complications of overweight and obesity are well established. They include, among others, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, gallbladder disease, sleep apnea, and some forms of cancer (

40). Many of these maladies are more common in some psychiatric populations (

4,

5,

41,

42). The therapeutic objectives in managing severe persistent psychiatric disorders include the reduction of excess mortality. The salience of medical disorders in excess mortality of all causes calls for clinical surveillance for obesity and its associated morbidity in all psychiatric patients.

Overweight and obesity are associated with stigma, decreased self-regard, treatment noncompliance, and a variety of indexes of harmful dysfunction (e.g., work maladjustment). Obesity may also complicate treatment response and the course and outcome of some psychiatric disorders. For example, Fagiolini and associates (

18,

20,

43) have reported that obesity and bipolar disorder are correlated with a longer time to recovery, higher risk of recurrence (notably for depression), suicidality, and a greater number of prior affective episodes.

7. What is the metabolic syndrome?

The term metabolic syndrome has been used interchangeably with several other monikers (e.g., syndrome X and insulin resistance syndrome). This syndrome denotes a clustering of cardiovascular and metabolic disturbances that may share a common pathophysiology. Not all affected persons manifest all dimensions of the metabolic syndrome. For example, up to 5% of the general population who do not have excess weight may be “metabolically obese” (

44). It is estimated that the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the general population is approximately 20%–25%, and in some psychiatric populations, perhaps higher (

45,

46). Several definitions have been formulated for the metabolic syndrome. Health care providers should be familiar with the definition proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program (Table 7).

8. What are the management strategies for obesity?

The evidence-based guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health (

48) suggest the need for weight loss in obese persons and in overweight persons who have two or more risk factors for obesity-related diseases. The edifice for any successful weight loss program is a healthy, balanced diet, along with increased physical activity.

Some patients are at risk of rapid weight gain from taking atypical antipsychotics. For example, a post hoc analysis of data on patients treated with olanzapine (

49) reveals that approximately 15% are at risk of rapid weight gain (defined as gaining 7% or more of their baseline weight within 6 weeks of initiation of therapy). These data suggest that weight gain monitoring should be particularly close during the first 2 months of administrating the medication.

It has been established that relatively modest reductions in weight are associated with clinically significant health benefits. The provision of basic education on weight management and healthy dietary choices is an inexpensive and effective intervention. Yet, unfortunately, most obese persons do not routinely receive weight loss advice from their primary health care provider (

42,

50).

Screening of the patient’s dietary habits, eating behaviors, and concomitant drug and alcohol use and screening for obesity-associated morbidity and family medical history are integral components of evaluation and monitoring (

51). Patients need to be informed about the differences in caloric density in commonly consumed foods and beverages and be counseled on smoking cessation and reasonable alcohol use (

52). The physical and mental health benefits of weight loss need to be clearly presented along with practical resources for exercise that are accessible and affordable (

3,

53,

54). Body weight, BMI, and WHR should be measured and monitored routinely, with baseline measurements and then semiannual measurements at minimum, and more frequent monitoring for patients who have experienced substantial weight gain.

9. What medications are effective for antipsychotic-associated weight gain?

Bariatric pharmacotherapy is recommended for adults who have a BMI ≥ 30 as well as for adults who have a BMI ≥ 27 along with obesity-related medical conditions (

10). No pharmacological treatment for antipsychotic-associated weight gain has been proven to be reliably efficacious and safe, although several medication approaches are being studied (

55,

56). The best available efficacy evidence is for sibutramine and topiramate. Amantadine, metformin, orlistat, and nizatidine are alternatives, but their use is associated with many hazards (e.g., exacerbation of psychosis) (

57–

74).

10. What behavioral interventions are effective for psychiatric patients?

As noted, a weight loss program should begin with a healthy, balanced diet and an increase in physical activity, along with education on nutrition, diet, the benefits of weight loss, and appropriate resources for exercise.

Several reports have examined the effectiveness of behavioral strategies for weight management in psychiatric patients (see McIntyre et al. [

75] for a comprehensive review). Vreeland and colleagues (

76) examined the effectiveness of a 12-week multimodal weight management program among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (intervention group, n=31; control group, n=15). All patients had been receiving an atypical antipsychotic for at least 3 months and had a BMI ≥ 26, or they had experienced a weight gain of ≥ 2.3 kg within 2 months of initiating the index medication. The program emphasized nutritional counseling, exercise, behavioral interventions, and healthy weight management techniques. At the end of the study period, patients assigned to the intervention group lost significantly more weight (mean loss, 2.7 kg or 2.7% of body weight) than patients assigned to the control group (mean gain, 2.9 kg or 3.1% of body weight). The corresponding mean change in BMI was a drop from 34.32 to 33.34 (2.8%) in the intervention group and an increase from 33.4 to 34.6 (3.6%) in the control group.

A report on the combination of exercise and the multicomponent Weight Watchers program (

77) indicated that there were no statistically significant changes in BMI in patients with schizophrenia who were treated with olanzapine (n=21). Menza and colleagues (

78) evaluated the effectiveness of a multimodal 12-month weight management program offered over 12 months to patients with schizophrenia who were treated with antipsychotics (n=31) who had gained significant weight. The intervention group experienced a significant loss of weight (3.0 kg) and reduction in BMI (5.1%), with favorable effects on blood pressure.

The evidentiary base supporting nonpharmacological approaches for medication-associated weight gain in psychiatric populations (

76,

79–

82) is sparse; this is clearly an area that requires further research. Nevertheless, the assertion that behavioral strategies are acceptable to psychiatric patients and beneficial for treating excess weight has preliminary support in the available research, and these strategies should have a salient role in the management plan.

Conclusion

The estimated prevalence of excess weight is increasing in the general population, and excess weight is particularly common in patients with mood and psychotic disorders. Several psychotropic medications, notably antipsychotics, are associated with clinically significant weight gain. Excess weight is associated with medical and psychiatric adversity, medical morbidity, and premature mortality. Patients with mood and psychotic disorders should be considered metabolically vulnerable. Routine screening, monitoring, and targeting obesity for treatment in psychiatric populations is a primary therapeutic objective.