Bipolar illness is considered one of the most genetically mediated disorders, yet the role of environment may be markedly underestimated. For example, although there are high concordance rates of bipolar disorder in identical twins, a number of studies suggest that this rate is only approximately 50 to 60%, leaving considerable room for other influences (

Allen, 1976;

Craddock & Jones, 1999;

Kieseppa, Partonen, Haukka, Kaprio, & Lonnqvist, 2004). Similarly, although there is a high incidence rate of bipolar illness in families, about 50% of patients with bipolar illness do not have a positive family history of bipolar illness in first-degree relatives (

Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002;

Suppes et al., 2001), again suggesting contributions from other influences. To the extent that bipolar illness emerges as a polygenic disorder (involving multiple gene vulnerabilities, each of small effect), it could be argued that genetic vulnerability also plays a role in those without a positive family history of bipolar illness, that is, individuals who do not have bipolar illness may pass on sufficient mixes of susceptibility genes such that the illness emerges in the next generation (

Comings, 1995;

Payne, Potash, & DePaulo, 2005).

Yet, the identical twin data noted indicate that this polygenic concept is not an adequate explanation, and it is likely that environmental influences are also very much involved. In this paper we review selected aspects of the literature and present new data from the framework that the quality, severity, repetition, and timing of psychosocial stressors may exert very different influences on the emergence versus progression of both affective episodes and the many comorbidities that are overrepresented in bipolar disorder.

We believe this developmental perspective is not only of theoretical and conceptual interest, but also of clinical therapeutic importance as well. Although there are currently no available therapeutic tools to alter one’s genetic vulnerability, there are multiple opportunities throughout one’s life (both before and after bipolar illness onset) at which important therapeutic maneuvers can be timed to and targeted at the effects of psychosocial stressors. Such interventions could involve not only more traditional secondary and tertiary prevention, that is, after syndrome or symptom onset, but also the possibility of primary preventive measures as well.

Stress can also play a role in the onset and maintenance of a variety of comorbidities to which bipolar patients are particularly vulnerable. There is, by definition, a fundamental involvement of environmental stressors in the etiology of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but also in the onset, maintenance, and relapse/recurrence of comorbid substance abuse disorders, such as alcohol and stimulant abuse.

Therefore, therapeutic attention directed toward the complex role of psychosocial stressors in the course of bipolar illness and its comorbidities could have a substantial public health impact, and potentially help prevent many of the grave consequences and disabilities associated with bipolar illness. Given the potential positive consequences of such effective intervention, we would hope that this and related papers in this issue help lead to more definitive consensus guidelines for the treatment of bipolar illness within the current health care systems in the United States and in other countries throughout the world. Currently, a positive, prospective, longitudinal, therapeutic approach to the wide array of psychosocial issues typically associated with bipolar illness is relatively underappreciated and underutilized.

Thus, this paper has two main components. The first component is clinical and preclinical data on the role of psychosocial stressors in behavioral neurobiology and the onset and course of bipolar illness. The second is an attempt to outline how to better apply the implications of these data for clinical therapeutics. A series of specific illustrations and suggestions are offered in the hope of more rapidly addressing this area of clinical and public health need in a practical fashion.

Implications for therapeutics

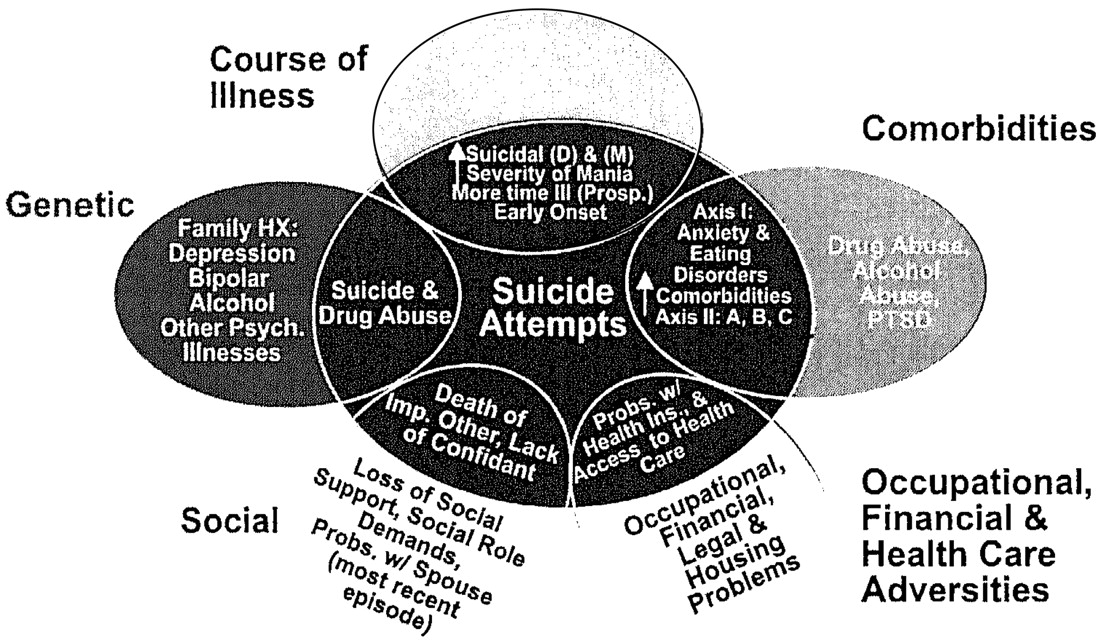

The data reviewed here about the potential role of psychosocial stressors in the early onset and progression of both bipolar illness and its comorbidities (Figure 5) suggest a wealth of opportunities for therapeutic intervention at the level of both primary and secondary prevention. Considerable data support the use of a variety of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational programs in not only changing attitudes about bipolar illness, but also in achieving overall better illness outcomes.

Psychosocial interventions

The efficacy of the many different types of psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder compared with a variety of other circumstances (most typically, treatment as usual) in randomized, controlled clinical trials are reviewed in this volume and in detail by others (

Colom & Lam, 2005;

Miklowitz, George, Richards, Simoneau, & Suddath, 2003;

Otto & Miklowitz, 2004;

Otto, Reilly-Harrington, & Sachs, 2003;

Scott, 2001). This literature suggests a potent role not only for individual cognitive and behavioral psychotherapeutic approaches to interpersonal conflict and stress management, but also a critical role for general illness and treatment education of both patients and family members (

Miklowitz et al., 2003;

Pavuluri et al., 2004).

Psychoeducation typically includes better illness awareness and, importantly, daily symptom monitoring (

Leverich & Post, 1996,

1998;

Miklowitz, 2002), particularly for the beginning of symptom breakthroughs that may herald the onset of a more severe episode. At the same time, approaches to management of the stressors that may be particularly pertinent to an individual’s vulnerable areas are also emphasized (

Colom et al., 2003;

Vieta & Colom, 2004).

Of interest, although the strength of this literature on controlled psychotherapeutic interventions often exceeds that of many experimental psychopharmacological manipulations that are widely used and justified on the basis of highly preliminary evidence, the data on psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational approaches appear to be less widely applied and accepted, and are even interpreted much more conservatively by the authors and proponents of these studies (

Scott, 2001;

Vieta & Colom, 2004;

Vieta et al., 2005). Caveats about the preliminary nature of the conclusions and the need for further specification of the critical components of therapy mediating a positive outcome are noted, but should not be used to downplay the immediate need for more systematic clinical application of existing approaches. Although in need of extension and specification, the findings are already sufficiently robust to justify the recommendations that these modalities be used more consistently and be included in a more concerted fashion in treatment guidelines.

Psychoeducation.

Illness education and management have become an integral part of the therapeutics of managing child- and adolescent-onset diabetes, with the view that careful monitoring and patient participation are crucial to maintaining good control of glucose levels and subsequently having a beneficial effect on long-term prognosis (

Weinzimer, Doyle, & Tamborlane. 2005). These educational and monitoring processes were widely utilized both before and after the recent definitive evidence that such tight regulation did lessen late-life sequellae such as MI. It would be almost inconceivable that a diabetes patient would receive medication and only a perfunctory set of instructions about injecting oneself with

X, Y, or

Z doses of insulin and coming back to see the physician in a few months. Yet, parallel limited illness education and instructions too often are given in the treatment of a first or later episode of bipolar illness. It is disappointing that, even after a more serious episode requiring hospitalization for mania or for depression because of suicidality, postdischarge follow-up instructions are often similarly lacking in substance, detail, reinforcement, and ongoing modification as new data on the degree and completeness of an individual’s clinical response become available.

Given the data on the role of psychosocial stressors in the precipitation and progression of both bipolar illness and its comorbidities and the data supporting the superiority of systematic psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational approaches compared with treatment as usual, a compelling argument at present can be made for enhanced therapeutic maneuvers specifically aimed at these variables (

Scott & Colom, 2005).

Building a medical team and support network.

The task of building a medical team and support network has been expertly enumerated by

Miklowitz (2002), and should become essential reading for every patient with bipolar disorder and his or her family members. Inherent in this process is the development of a careful longitudinal monitoring strategy, such that small symptom variations can directly feed back into therapeutic decisions, not only for modified psychopharmacological interventions, but also for additional psychotherapeutic ones as well. We have found that a global or cursory assessment of one’s mood status is not a sufficient means of monitoring the details of an individual’s course of illness that may fluctuate widely in a much higher percentage of patients with bipolar illness than had previously been surmised.

Daily charting of mood

Based on careful but widely spaced assessments, the extent of mood alterations that occur within a patient within weeks or within several days is usually underestimated (

Kupka et al., 2005;

Nolen et al., 2004;

Post et al., 2003). Approximately 42% of carefully assessed bipolar outpatients in the SFBN reported a history of rapid cycling, and in the first year of prospective follow-up, 38% of patients had confirmation of at least four episodes per year despite intensive treatment. More remarkable was the report that 18% of patients had ultrarapid cycling, that is, four or more episodes within a month, and some 19% reported ultra-ultrarapid (or ultradian) cycling in which major mood fluctuations occurred one or more times within a 24-hr day (

Kupka et al., 2005;

Leverich et al., 2003). We cite these data as further evidence that this large group of patients require careful (preferably daily) prospective record keeping of their mood fluctuations.

For the young child, daily mood charting must of necessity be done by a parental or other caretaking figure, but most older individuals can readily manage daily self-ratings. We recommend the National Institute of Mental Health Life Chart Methodology (NIMH-LCM) as an easy to use format and one that has both a capacity for both self-rating, and rating by others or clinicians in parallel (

Leverich & Post 1996,

1998). The NIMH-LCM also has a modified version for symptomatic description of excited activated behaviors versus inhibited and depressive ones in children, in whom accurate characterization of behavior may be crucial to both acute and long-term management. Particularly given the high incidence (

Leverich et al., 2003;

Leverich, McElroy, et al., 2002;

Perlis et al., 2004) but considerable ongoing controversy about diagnostic thresholds (

Post & Kowatch 2006), the kiddie LCM (K-LCM) rating of symptom severity based on its degree of associated dysfunction (without taking an arbitrary position on diagnostic category) may be especially important for precise longitudinal monitoring of affective and comorbid symptomatology and its response to treatment.

Development of early warning systems and intervention drills

Such an ongoing daily assessment by the patient or parent provides a tool for evaluating drug and psychotherapeutic interventions on a much more precise and targeted time frame. Such careful monitoring provides that basis for developing an early warning system (EWS) pertinent to each individual (

Post & Altshuler, 2005;

Post, Speer, & Leverich, 2006). In child or adult instances of symptom breakthrough, specific degrees of altered mood or sleep are specified in advance that will trigger actions ranging from dose modifications, calls to the physician or therapist, or related therapeutic maneuvers. Such monitoring and EWS approaches are routine in diabetes and blood pressure monitoring, for example.

These EWS efforts are like smoke alarms, directed at maintaining a remission and attempting to avoid more major manic or depressive episode occurrence in which immediate intervention is needed on an emergency basis. As part of a full-fledged fire drill for such an emergency, the patient and family members should know the typical characteristics of such an occurrence, whom they should contact, and where they can take the patient for immediate treatment.

Similarly, cognitive and behavioral approaches should be specifically targeted to issues of medication compliance (adherence). In most serious medical conditions, noncompliance is highly prevalent and markedly underestimated. We know this is also the case in bipolar illness in which both manic and depressive mood states themselves further increase the likelihood of not only missed doses, but ceasing taking medication altogether (

Keck et al., 1996).

Basco and Rush (1996) deal very effectively with many of these compliance issues.

Therapeutic approaches to reducing the impact and consequences of stressors

Coping strategies.

Equally important is an active approach to stress anticipation and management. We know from studies in animals that profound behavioral and neurochemical consequences greatly depend on the “psychological” constructs inherent in the experimental paradigm. That is, an animal given control over the ability to terminate a shock stress does not acquire the same helplessness syndrome or neurochemical abnormalities as its yoked control animal that receives precisely the same amount of physical stressor (

Seligman & Beagley, 1975).

Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy.

Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy is well suited for helping patients achieve a greater degree of control and, in the process, learning a variety of long-term coping strategies. The data in both unipolar illness, as noted by

Fava and colleagues (2004), and an emerging literature in bipolar illness (noted above), also strongly support the importance of such approaches for a variety of positive therapeutic endpoints, including better relapse prevention.

Interpersonal psychotherapy.

In a related fashion, interpersonal psychotherapy, although less systematically tested in bipolar compared with unipolar illness, has much face validity in dealing with issues of job stress and discord within one’s social network which (as seen above) are important precipitants of both initial affective episodes and their recurrences.

Type of education as a function of stage of illness.

We have discussed the possibility that one should specifically tune the nature of the psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic interventions to the stage of illness that one is attempting to alter. Ongoing psychoeducational efforts would appear to require modification as a function of stage of illness evolution, severity of symptomatology, and an individual’s basic knowledge or ignorance of the illness, its psychopharmacology, and stress management techniques.

Education about the acute management of a full-blown acute manic or depressive episode must necessarily differ from the educational efforts aimed at monitoring and maintaining a remission. The nuances of self-monitoring and the details of a variety of psychopharmacological approaches that may be required in the management of bipolar illness can be daunting, and would appear to require an ongoing and evolving psychoeducational effort (Post & Leverich, in press). For the vast majority of patients with bipolar illness, this cannot be accomplished in a 20-min medication management visit on a monthly or less frequent basis. More time needs to be allotted to the endeavor and, as needed, supported and enhanced by other clinical members of the treatment team.

Type of therapy as a function of course of illness: Representational versus habit memory.

More dynamic and interpersonal psychotherapeutic techniques may be pertinent to initial phases of illness when stressors are intrinsically involved, but in the patient who has developed episode automaticity, other approaches would appear indicated. This transition to more spontaneous episode occurrence might be somewhat similar to the transfer of learning and memory mechanisms from those that are associative or declarative and dependent on amygdala and hippocampal systems of the medial-temporal lobe (representational memory), to those involving repeated learning and training where the memory trace appears to reside in neostriatal and, potentially, cerebellar systems (putatively mediating habit memory;

Mishkin & Appenzeller, 1987). When affective episodes begin to occur on a more automatic basis, there may be a similar transition in the neural structures mediating their occurrence in a fashion parallel to the transition from representational to habit memory mechanisms.

Such a transition appears to occur in the area of substance use and abuse as well. For example, in psychomotor stimulant administration, the amygdala is crucial for initial associative aspects of environmental context-dependent behavioral sensitization after one high dose of cocaine (

Post et al., 1987), but after multiple high doses of cocaine, the amygdala is no longer required and the nucleus ↑ accumbens and other neural substrates appear to become more intimately involved in the behavioral sensitization process.

This type of transition in the processes and neural structures mediating behavioral sensitization perhaps parallels the clinical difficulties in deconditioning cues associated with relapse to active substance abuse. After a period of acute abstinence a patient may cognitively assume and feel that they are “immune” from associative cues triggering a craving for cocaine or other psychomotor stimulants, but in actuality, they continue to show autonomic and other unconscious reactions to presentations of drug-related cues and related stressors (

Childress, McLellan, Ehrman, & O’Brien, 1988;

O’Brien, Childress, McLellan, & Ehrman, 1992). Their relapse into active drug use in the face of minor cues or stressors may appear automatic and not even have an active cognitive component, catching them unaware as well.

In this situation of increased automaticity, it would also appear that different techniques, that is, ones that are systematically practiced and overpracticed, are required to further desensitize these now ingrained responses to drug-related cues. Knowing a specific and practical range of behaviors useful in overcoming such breakthrough cravings is of further aid in preventing relapse (

Childress, McLellan, Ehrman, & O’Brien, 1987;

O’Brien, Childress, McLellan, & Ehrman, 1993). We would submit that dynamic psychotherapies are not as appropriate for this late stage of cocaine relapse prevention as more systematic and practice-based techniques aimed at modifying the habit memory system, including those developed in 12-step programs or similarly constructed therapies. Also, psychotherapeutic work may need to proceed from mourning the loss of the “well self” at the onset of a first bipolar episode to a reevaluation and appropriate setting of short- and long-term goals in the mid phase of illness, to perhaps existential and related psychotherapeutic techniques for a late stage of illness wherein one has to adapt to certain residual problems and disabilities that may no longer be treatment responsive.

A special caveat is warranted in relation to this last point, however. We have repeatedly seen that patients who are apparently al a late and refractory stage of their illness can achieve surprising and often dramatic degrees of clinical improvement once the appropriate therapeutic regimen is instituted. This also appears to be true for patients who appear to have life-long problems with anxiety or PTSD comorbidities, apparent Axis II personality disorders, or associated “character” traits; these can at times almost “magically” disappear when mood and behavior are adequately stabilized with the appropriate psychopharmacological and therapeutic regimens. Thus, it benefits both patient and therapist to continue to assume that notable therapeutic progress is possible at virtually any stage of illness evolution or severity of manifestation.

Here, it is also important to reemphasize the point that the notions of kindling and sensitization that apply to the untreated or inadequately treated illness (

Post, 1992,

2004c;

Post et al., 2000) do not imply that cycle acceleration, automaticity, and treatment resistance are progressive or invariant outcomes as some have misinterpreted the theory and predictions of outcome. Specific types of treatment can almost always be applied to the manifest illness, although it may take increasingly complex and more heroic measures later than earlier in illness evolution (

Frye et al., 2000).

Moreover, patients often come to a psychopharmacological consultation with the statement that they have tried all of the drug approaches to bipolar illness, when in reality they have had only preliminary and cursory exploration of the very wide range of agents now available. This increasingly wide range of therapeutic options for both the primary and comorbid conditions needs to be dealt with in the appropriate psychoeducational framework without overpromising immediate therapeutic benefit or ultimate symptom remission. For example, a drug such as topiramate, which is not effective in the treatment of acute mania in adults, may nonetheless be helpful in comorbid alcohol use, cocaine use, PTSD, eating disorders, and obesity, as reviewed elsewhere (

Post, 2004a,

2004b,

2005). Thus, a considerable amount of polypharmacy and polypsychotherapy may be required to match the panoply of bipolar presentations and comorbidities.

In contrast, in a patient who is in the early stages of bipolar illness after only several episodes or is currently in a substantially improved state, we have found the utility of discriminating the notion of achieving “perfection” in the psychopharmacological as opposed to the psychotherapeutic realm. For many with unipolar and bipolar illness, the striving for psychological perfection is problematic and is a target for psychotherapeutic amelioration in the service of a more successful outcome. In contrast, emphasizing that the psychopharmacological goal is for “perfection” in terms of achieving and maintaining a full remission would appear to have some merit as it pertains to hopefulness, compliance, and the required monitoring intensity, such that minor symptoms can be dealt with before they become problematic. Stating that this type of perfection can be an agreed upon goal of long-term maintenance therapy often evokes a very favorable response on the patient’s part, because this has often been their secret goal all along, that is, achieving and maintaining an essential remission, and they are pleased that this is also supported by the treating clinician and physician.

Examples of practical adjunctive psychosocial interventions for those at high risk

When considering a shift in public health approaches to early intervention in children at high risk for an affective disorder, it would appear appropriate to start such a consideration with the areas that would likely have both the greatest impact and engender the least controversy.

Supports for those with postpartum depression

The postpartum period is a difficult time for almost any family, and if it is complicated by the presence of maternal depression, can be overwhelming. Thus, in obstetrics-gynecology practice, screening for depression both pre-and postpartum should be routine and no more overlooked than assessment of temperature, pulse, and blood pressure. Yet, it is rarely accomplished in a systematic fashion despite the common incidence of this condition, that is, almost 20% of all pregnancies (

Gavin et al, 2005). Similarly, as the medical attention following the delivery is shifted from the mother to the intermediate and long-term care of the neonate, pediatricians should make the evaluation of maternal depression part of their routine child health care repertoire. Although these measures have often been suggested, a major gap remains in practice (

Seehusen, Baldwin, Runkle, & Clark, 2005).

The importance of these screening measures needs to be taught as part of a routine practice in medical school, recommended in textbooks, and mandated as part of good practice by appropriate medical societies. Yet, each group is likely to say that such “extra” work and assessment is the purview of the other or another physician group, such as those involved in general care and family medicine, or specifically a psychiatrist. Left to this general sentiment, the needed changes are highly unlikely to occur until many years in the future. Another possible way to circumvent the inherent multiple public health, attitudinal, and systems difficulties, is to popularize the notion that pregnant individuals and newborns’ mothers should complete a readily available self-assessment scale and present the data to the appropriate specialist or generalist for subsequent evaluation and the appropriate action of treatment or referral if needed.

A number of recent studies have indicated that the notion of relative immunity from depression during pregnancy in someone with recurrent depression or bipolar disorder is, in fact, a myth (

Cohen et al., 2004,

2006). Moreover, these individuals have a subsequently higher risk for a postpartum depression than the general population, and this needs to be considered as well.

Some practical suggestions for possible altered approaches to intervention and assistance once a diagnosis of postpartum depression has been reached are offered here in the spirit of starting a dialogue on what might be the most; appropriate interventions for individuals in other circumstances as well, and not with the idea that these are necessarily the best, most practical, or cost effective. The fact that they are often quite different from current practice and might engender considerable controversy would appear to help make the point that these and related measures for stress reduction and illness management deserve at least active discussion.

Because most US hospital stays for pregnancy and delivery have been drastically reduced from the previous routine of several days to the current 1 day or only overnight, it would appear reasonable that some of the loss of careful acute follow-up could be recouped by the provision on a regular basis of a home healthcare visit by a nurse practitioner on perhaps a once per week basis for the first month postpartum. This hypothetical individual’s agenda would be not only the assessment of vital signs and general maternal healthcare issues, but also a modicum of instruction about well baby care and facilitating the completion of observer and/or self-rated depression inventory for the new mother. For those found to have a postpartum depression, this individual could be recommended to continue weekly visits for the next several months. Moreover, this individual could assist in the referral and treatment acquisition process for more formal psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological intervention as needed.

Conceptual approaches to building new support systems

Ideally, the depressed mother should also have someone available who could provide brief periods of child care assistance when she is overwhelmed and without other live-in resources. It would appear that the assignment of a person to provide the mother with a brief respite (i.e., a “time out” and a backup telephone number) would be a good starting place. If the baby is inconsolable and the mother exhausted, depressed, and demoralized, such a resource might be invaluable. This person could be conceptualized very much like the sponsors assigned in Alcoholics Anonymous who can be called if one is at high risk for ending their sobriety. This time-out individual would need to be viewed in a nonpejorative way as part of the routine treatment of postpartum depression and available to all mothers suffering from this potentially disabling disorder. As in Alcoholics Anonymous, the timeout person could be an unpaid volunteer, thus mitigating what would otherwise be an extraordinarily expensive medical supplement.

The older, multigenerational, extended-family structure used to provide such individuals on an almost round the clock basis in the person of a grandparent or other live-in family member. As the median number of adults per household in the United States is now two (and one is often away working) and there are very high numbers of single parent families, some modicum of this type of substitute grandparental or family relative support might need to come from the outside if it were to come at all.

Current mental health associations, advocacy groups, and foundations focused particularly on this issue of providing supplemental care for the mother with postpartum depression, and later, other aspects of bipolar illness itself, might be well suited to the task of developing such an endeavor. With the many millions and ever growing numbers of now well-bodied, highly experienced parents, grandparents, and great grandparents in retirement, such a group of older individuals could provide a very large pool for recruitment of volunteers. A several-tiered system might be necessary to respond to different levels of need. Some volunteers could staff telephones for advice, assistance, and support, while others with access to vehicles could be available for several hours for timeout duty at an individual patient’s residence when requested.

Need for immediate action

Critics would appropriately ask what evidence exists to support the effectiveness of such strategies as a visiting nurse and a time-out volunteer. A traditional way of proceeding is to gather preliminary and pilot study data first in order to justify such an effort. However, an alternative strategy may be more timely, efficient, and cost effective, that is, these and related types of programs that have both face validity and support from analogous efforts found effective in other areas of psychiatry and substance abuse prevention and intervention. Not only do Alcoholics Anonymous and related programs have proven positive track records, but they also often have controlled clinical trial data to document effectiveness. Moreover, a wealth of studies now document the short- and long-term efficacy of even minimalistic interventions, such as having a weekly visit by a nurse in homes with children at high risk (although not necessarily because of a mother’s postpartum depression). These studies show that these visits are associated with long-lasting positive effects that can be documented on measures such as increased high school graduation rates, and decreases in substance abuse and arrests compared with the control conditions (

Eckenrode et al., 2001;

Olds et al., 1999).

An important “negative” reason for not proceeding with the traditional mode of first demonstrating efficacy and then inaugurating these programs into more formal policies is the robust literature cited about the efficacy of psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational therapeutic modalities in bipolar illness compared with treatment as usual. Despite this small, but overwhelmingly positive literature, few of the studies definitively recommend that these measures now be incorporated into routine health care policy. Moreover, both supporters and critics of these studies point out that additional controlled studies are necessary to more adequately elucidate the nature of the “critical ingredients” mediating the success. Thus, the process of specification could prove relatively unending (perhaps requiring decades) before supporters and critics alike are satisfied with the fact that a given program has specified the precise mechanisms mediating efficacy.

Instead, it would appear vastly more efficient from both a time and cost perspective to inaugurate such face-valid programs from the outset and then perform appropriate efficacy and effectiveness studies during implementation. One could compare the relative effectiveness of two different interventions. This would not only allow study in situ, but revision of aspects of programs that appear most problematic and enhancement of others that appear particularly effective.

Training patients and advisory group members as educators

Although several novel public health measures in postpartum depression are discussed here in some detail, they are meant to be illustrative of similar policies, procedures, and studies directed al the many areas of vulnerability (discussed above) in those either at high risk or already with a diagnosis of bipolar illness. The development of programs in postpartum depression could also be used in applying similar types of strategies at each of the target points already shown to be associated with eventual prognosis in bipolar illness.

The former National Depressive and Manic Depressive Association (now the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance) is proceeding with projects that involve formal training of patients to be peer supports and illness educators. The effectiveness of this type of paradigm has been demonstrated in Georgia and other states and venues. It could be immediately inaugurated, enhanced, and studied more widely, as sequenced in that order, respectively. Volunteer organizations can do what public health policy experts cannot readily do, that is, proceed immediately with much needed support services prior to the more academic, conventional, and ideal way of first demonstrating effectiveness and then changing procedures based on hard facts.

The imperatives for early action

In this paper we would redefine what are the critical facts that should be taken into consideration, however. The hard facts, documented above, are that bipolar illness in general is vastly underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Those with early-onset bipolar illness are at very high risk for a difficult, complicated, and partially treatment-resistant illness. First treatment can be delayed for decades and current treatment paradigms are poorly delineated. This ongoing inadequate approach to the illness has very grave and potentially life-long and life-threatening consequences for many individuals; it is a current and continuing disaster of huge personal, financial, and societal proportions (

Post & Kowatch 2006). Waiting for other hard facts from the results of multiple controlled clinical trials would likely delay needed supplemental health care services to millions of individuals (in the United States alone) for many years if not decades.

Our current US health care system, which too often follows the principle of cutting immediate costs and services (many times at the expense of long-term savings and positive outcomes) in both the private and public arenas, is ill equipped, and one might say almost perfectly mismatched to the real needs of patients with bipolar illness. These individuals require intensive early support and careful, consistent, long-term monitoring, and multimodal pharmacological treatment and psychoeducational approaches. Even in countries where health care is covered by the government for all individuals, there is a shortfall in the delivery of these long-term approaches on a routine basis.

The stress of having a young child with bipolar illness (whether or not the parents are currently ill or depressed) can be enormous and often dismissed with the euphemistic term of “caregiver burden.” Providing a periodic in-home support and time-out individual to the euthymic, or especially depressed or manic, mother, or distraught father with a child who is irritable, labile, hyperactive, impulsive, explosive, aggressive, who does not sleep as much as usual, and switches rapidly from euphoria to profound depression (whether this is eventually classified as bipolar I, II, not otherwise specified, or merely bipolar-like), may have long-term, positive, illness-modifying effects for both the parents and the child.

Like the support programs suggested for postpartum depression, such an adjunctive support system could be routinely provided to a parent by volunteers in this potentially difficult if not desperate situation. This would not be intended as an alternative, but a supplement to the family and psychoeducational therapy provided by physicians and psychotherapy-oriented clinicians, be they PhDs, social workers, or nurses. The additional availability of such a time-out person could provide needed stress reduction to the parent and, as a side effect, potentially reduce instances of verbal or physical abuse elicited by and directed toward the “impossible child.”

Given the often great shortcomings in the treatment of bipolar illness in every age group and at every stage and transition point in its evolution, a new series of initiatives, a few of which are outlined here and many others, are needed to begin to help fill the gaps and supplement what is too often currently accepted as treatment as usual.

With the number and richness of such opportunities for providing more optimal care by focusing on prevention, early intervention, psychoeducation, support, and stressor amelioration throughout the course of development for those at high risk, as well as those already diagnosed with bipolar illness, even small steps in this direction are likely to be highly beneficial for many individuals and for society in general (because of the enormous economic costs of the illness).

Although not yet demonstrated definitively, it is highly likely that even a modicum of improvement at just a few of the treatment gaps noted could have a very substantial impact. This likelihood is based on the existing controlled clinical trials literature on the considerable efficacy of focused psychoeducation and cognitive, behavioral, and other target psychotherapeutic modalities in moderating adverse illness outcomes. Routinely implementing some of these techniques, enhancing and supplementing them with some of the other approaches preliminarily outlined, and revising them as new data become available could have clinically important effects on the outcome of what otherwise can be a disabling illness.