IS CANNABIS A CAUSAL RISK FACTOR FOR PSYCHOSIS?

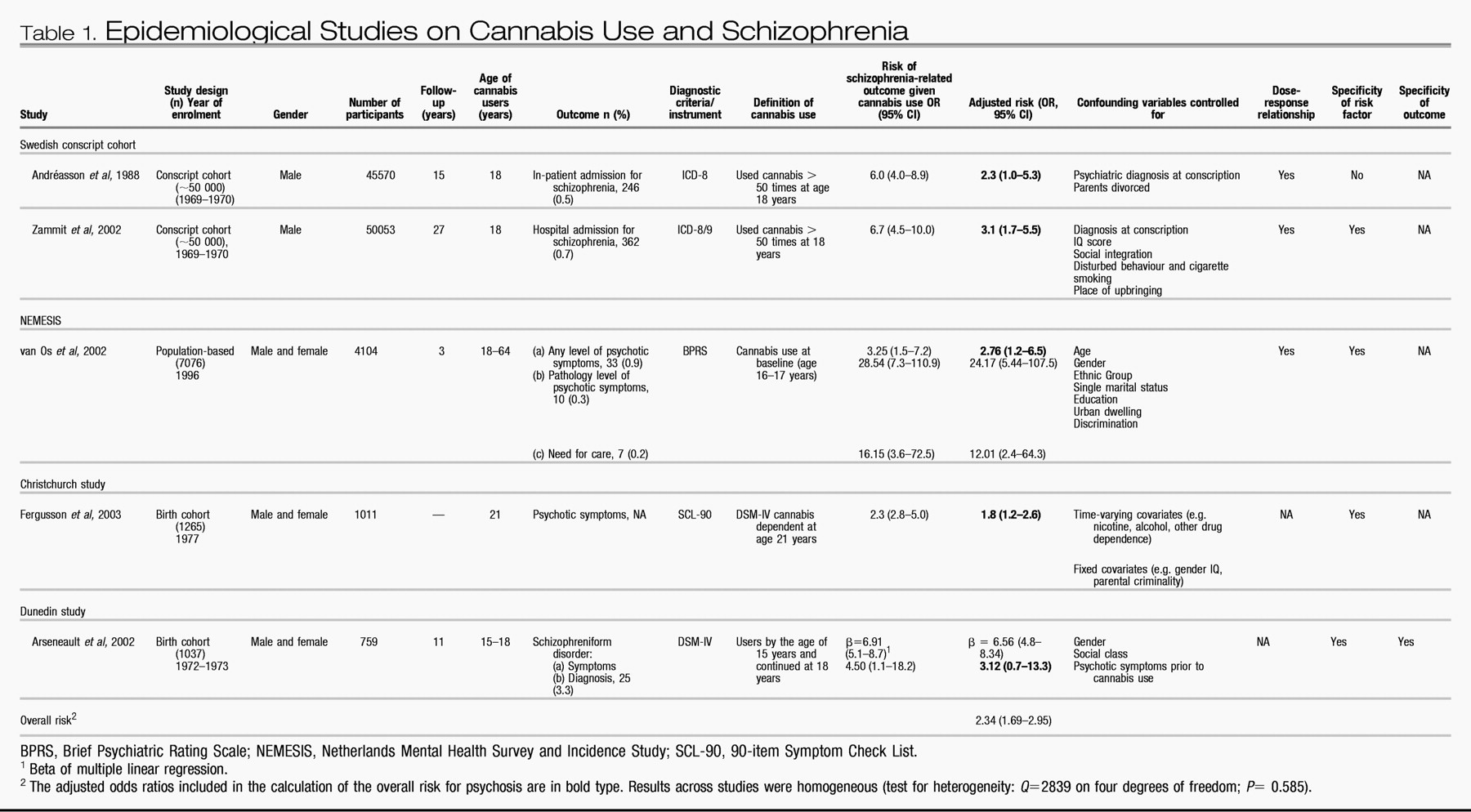

In this review we have tried to determine whether cannabis is a cause of schizophrenia. We have shown that all the available population-based studies on the issue have found that cannabis use is associated with later schizophrenia outcomes (

Table 1). All these studies support the concept of temporal priority by showing that cannabis use most probably preceded schizophrenia. These studies also provide evidence for direction by showing that the association between adolescent cannabis use and adult psychosis persists after controlling for many potential confounding variables such as disturbed behaviour, low IQ, place of upbringing, cigarette smoking, poor social integration, gender, age, ethnic group, level of education, unemployment, single marital status and previous psychotic symptoms. Further evidence for a causal relationship is provided by the presence of a dose-response relationship between cannabis use and schizophrenia (

Andréasson et al, 1988;

van Os et al, 2002;

Zammit et al, 2002), specificity of exposure (

Arseneault et al, 2002;

van Os et al, 2002;

Zammit et al, 2002;

Fergusson et al, 2003) and specificity of the outcome (

Arseneault et al, 2002). Overall, cannabis use appears to confer a twofold risk of later schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder (pooled odds ratio=2.34; 95% CI 1.69–2.95).

Methodological issues. Before discussing further the issue of a causal association between cannabis use and schizophrenia, it is important to point out some methodological limitations in the literature reviewed.

First, various measures of schizophrenia outcome were used in these studies: hospital discharge, pathology level of psychosis, psychotic symptoms and schizophreniform disorder. The heterogeneity of the outcome makes it difficult to draw a firm conclusion on schizophrenia per se from the findings reported by these studies. However, all studies converge in showing an elevated risk for psychosis in later life among cannabis users.

Second, all measures of cannabis use in these studies were based on self-reports and were not supplemented by urine tests or hair analysis. In this situation, under-rather than over-reporting is possible. Therefore, the use of self-reported data would under-estimate the magnitude of the association between cannabis use and later schizophrenia, rather than giving rise to a spurious association. In fact, in the Dunedin study and the Christchurch study participants have learned after many years of involvement with the study that all information they provide remains strictly confidential and therefore their answers are likely to provide a good estimate of actual levels of drug use in those populations (

Arseneault et al, 2002;

Fergusson et al, 2003).

Third, there is limited information on other illicit drug use. It would be informative to gather more precise information about other illicit drugs used by young people to control more effectively for possible confounding effects of, for example, stimulant drug use. However, difficulties related to statistical power are likely to occur because of the small number of individuals reporting such use.

Fourth, most studies were unable to establish whether prodromal manifestations of schizophrenia preceded cannabis use, leaving the possibility that cannabis use may be a consequence of emerging schizophrenia rather than a cause of it. Findings have indicated that schizophrenia is typically preceded by psychological and behavioural changes years before the onset of diagnosed disease (

Jones et al, 1994;

Cannon et al, 1997;

Malmberg et al, 1998). It is possible, therefore, that cannabis use may be consequent to an early emerging schizophrenia rather than predisposing to its development. Thus, it has become crucial to control for these early signs of psychosis to establish clearly the temporal priority between cannabis use and adult psychosis. Although the Christchurch study applied statistical control for previous psychotic symptoms, it is not clear whether the measure of psychotic symptoms at age 18 years preceded the onset of cannabis use. To date, the Dunedin study is the only study to demonstrate temporal priority by showing that adolescent cannabis users are at increased risk of experiencing schizophrenic symptoms in adult life, even after taking into account the childhood psychotic symptoms that preceded the onset of cannabis use.

Finally, there was limited statistical power in the studies using self-reports of schizophrenia outcomes (in the NEMESIS, the Christchurch and the Dunedin studies) for examining such a rare outcome. It will be important for future studies to examine larger population samples in order to assess a greater number of individuals with psychotic disorders.

Alternative explanations. One might speculate that cannabis is a ‘gateway drug' for the use of harder drugs (

Kazuo & Kandel, 1984) and that individuals who use cannabis heavily might also be using other substances such as amphetamines, phenylcyclidine and lysergic acid diethylamide that are thought to be psychotogenic (

Murray et al, 2003). Support for this explanation is provided by recent findings showing that the use of other drugs among young adults is almost always preceded by cannabis use (

Fergusson & Horwood, 2000). This is especially true for heavy cannabis users (50 times or more per year), who were 140 times more likely to move on to other illicit drugs than people who had not used cannabis before. However, in the Dunedin, Christchurch, Dutch and Swedish studies, the association between cannabis and schizophrenia held even when adjusting for the use of other drugs (

Arseneault et al, 2002;

van Os et al, 2002;

Zammit et al, 2002;

Fergusson et al, 2003).

A second possibility is that individuals who use cannabis in adolescence continue to use this illicit substance in adulthood and because cannabis use intoxication can be associated with transient psychotic symptoms (

Hall & Degenhardt, 2004;

Verdoux, 2004) this could account for the observed association. However, the diagnostic interview used in the Dunedin study explicitly ruled out a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder if psychotic symptoms occurred only following substance use.

A third possibility is that early-onset cannabis use is a proxy measure for poor premorbid adjustment, which is known to be associated with schizophrenia and other psychiatric outcomes (

Cannon et al, 2002).

Arseneault et al (2002) found that cannabis use was specifically related to schizophrenia outcomes, as opposed to depression, suggesting specificity in longitudinal association rather than general poor premorbid adjustment, although there is other evidence showing an association between cannabis use and depression (

Patton et al, 2002).

What kind of cause is it? We have shown, on the basis of the best evidence currently available, that cannabis use is likely to play a causal role with regard to schizophrenia. However, further questions now arise. How strong is the causal effect and is cannabis use a necessary or sufficient cause of schizophrenia (

Rothman & Greenland, 1998)?

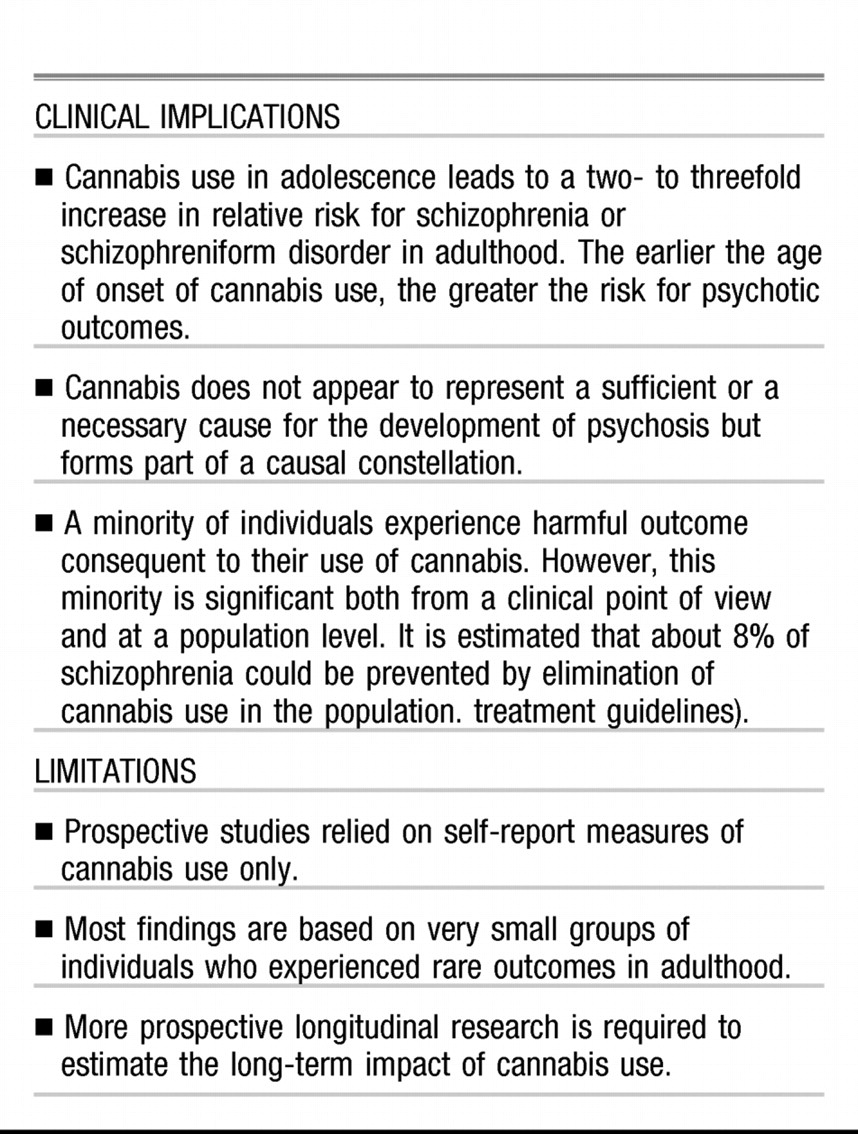

The studies reviewed earlier show that cannabis use is clearly not a necessary cause for the development of psychosis, by failing to show that all adults with schizophrenia used cannabis in adolescence. It is also clear that cannabis use is not a sufficient cause for later psychosis because the majority of adolescent cannabis users did not develop schizophrenia in adulthood. Therefore, we can conclude that cannabis use is a component cause, among possibly many others, forming part of a causal constellation that leads to adult schizophrenia.

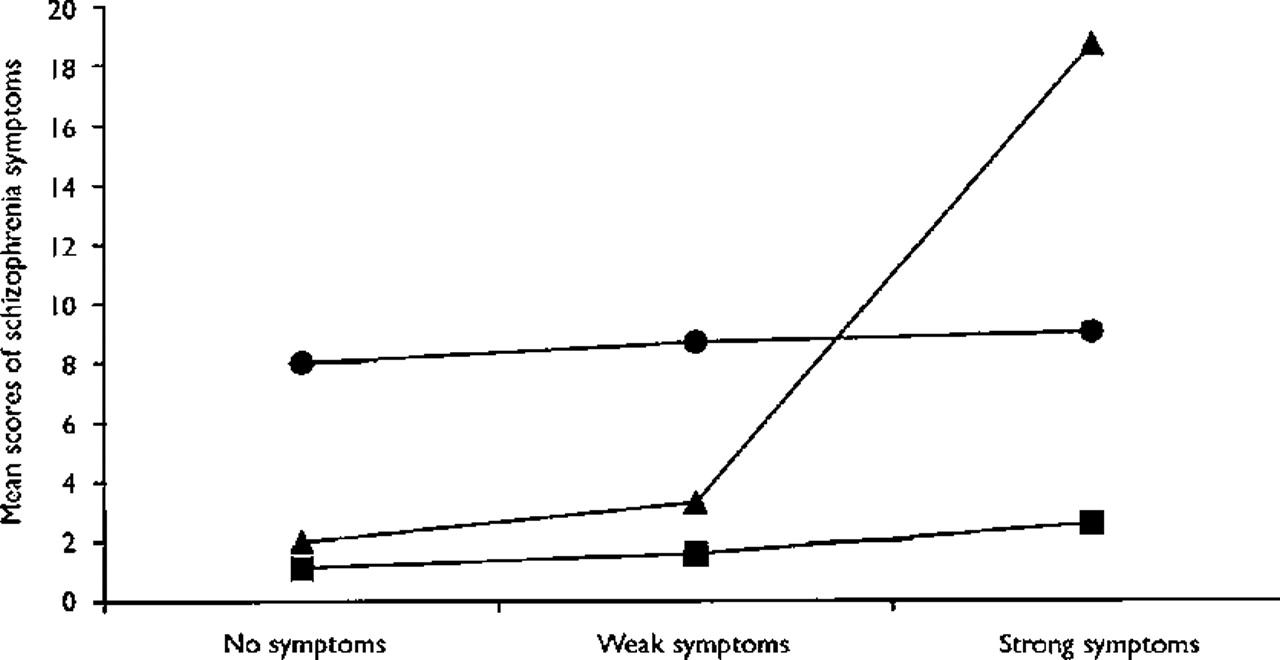

What might the other component causes be? Unfortunately, we get little insight on component causes other than cannabis from the studies reviewed in this article. Certainly, genes are likely to moderate the association between cannabis use and later psychosis by increasing the susceptibility of schizophrenic outcomes among early-onset cannabis users. However, no study yet has verified an interaction effect between candidate genes and cannabis use. Cannabis use appears to increase the risk of schizophrenia outcomes primarily among those individuals already vulnerable by virtue of pre-existing psychotic symptoms (

Arseneault et al, 2002;

van Os et al, 2002). A study of French undergraduate university students showed that the acute effects of cannabis were stronger among participants with high vulnerability for psychosis (by virtue of psychotic symptoms) (

Verdoux et al, 2003). Such vulnerable participants reported an increased level of perceived hostility and unusual perceptions, and also a decreased level of pleasure associated with the experience of using cannabis. However, this mediator effect (

Kraemer et al, 2001) is not a simple one.

Two studies explored the role of cannabis use in the development of psychotic symptoms in groups of young people considered to be at high risk of developing psychotic symptoms. An analysis of the Edinburgh High Risk Study found that both individuals at high genetic risk of schizophrenia (by virtue of two affected relatives) and individuals with no family history of schizophrenia were at increased risk of psychotic symptoms after cannabis use (

Miller et al, 2001). An Australian study followed up a group of 100 individuals who asked for help from an early intervention service centre (

Phillips et al, 2002). Cannabis use or dependence at entry to the study was not associated with the development of psychotic illness (transition to psychosis) over a 12-month period of follow-up after entry to the study. However, the low level of reported cannabis use among the group could indicate that the sample may not be representative of the population of ‘prodromal' individuals.

How strong is the causal effect? Can we say anything about the strength of the causal effect of cannabis for schizophrenia? We are somewhat hampered in this endeavour because the strength of any particular cause depends on the prevalence of the other component or interacting causes in the population (

Rothman & Greenland, 1998). As discussed above, we do not know for certain, at present, any other component causes in the ‘schizophrenia constellation'. We can make some broad suggestions. A component cause, even if it is very common, will rarely cause a disorder if the other component causes in the causal constellation are rare. This will hold regardless of the prevalence of the component cause of interest in the population or its role in the pathophysiology of the disorder. On the other hand, the rarer a component cause relative to its partners in any sufficient cause, the stronger that component cause will appear. Because cannabis use is relatively common in the population but appears to cause schizophrenia rarely, it would follow that at least one of the other component causes in the causal constellation is rare. Indeed, calculation of the overall risk for schizophrenia associated with cannabis use revealed that cannabis use confers only a twofold increase in relative risk for schizophrenia. But does this mean that we should not worry about cannabis as a causal factor?

There is another way of looking at this issue. Once a direct causal relationship between exposure and outcome is assumed, the strength of a particular association from a public health point of view can be assessed with the population attributable fraction. This gives a measure of the number of cases of the disorder in the population that could be eliminated (i.e. would not occur) by removal of a harmful causal factor. The population-attributable fraction for the Dunedin study is 8%. In other words, removal of cannabis use from the New Zealand population aged 15 years would have led to an 8% reduction in the incidence of schizophrenia in that population. The NEMESIS group reported higher population-attributable fractions, possibly because the outcome measures that they used did not exclusively include clinical psychosis cases (i.e. the need for care). However, even 8% is not an insignificant figure from a public health point of view. Because the possibility of eliminating cannabis use totally from the population is rather remote, it may be advisable to concentrate on those for whom adverse outcomes are more common (vulnerable youths).

If cannabis use can cause psychosis, how can we explain that, despite steadily increasing rates of cannabis use over past decades, the incidence of schizophrenia in the population has remained stable? First, with a population-attributable fraction of 8% the causal influence of cannabis use on the incidence of schizophrenia is probably not easily visible in the general population. Second, the Dunedin study showed that cannabis use in early adolescence (first reported use at age 15 years) was associated with the strongest effects on schizophrenia outcomes. Trends of cannabis use among adolescents in the USA indicate that cannabis use under the age of 16 years is a fairly new phenomenon that has appeared only since the early 1990s (

Johnston et al, 2002). One would therefore predict an increase in rates of schizophrenia in the general population over the next 10 years. Indeed, there is already some evidence that the incidence of schizophrenia is currently increasing in some areas of London, especially among young people (

Boydell et al, 2003).

Although the majority of young people are able to use cannabis in adolescence without harm, a vulnerable minority experience harmful outcomes. The epidemiological evidence suggests that cannabis use among psychologically vulnerable young adolescents should be strongly discouraged by parents, teachers and health practitioners alike. Findings also suggest that the youngest cannabis users are most at risk (

Arseneault et al, 2002), perhaps because their cannabis use becomes longstanding. This should encourage policy and law makers to concentrate their effort on delaying the onset of cannabis use. At the same time, further research is needed on the long-term impact of frequent cannabis use that begins at an early age and on the possible mechanisms by which cannabis use can lead to psychosis.