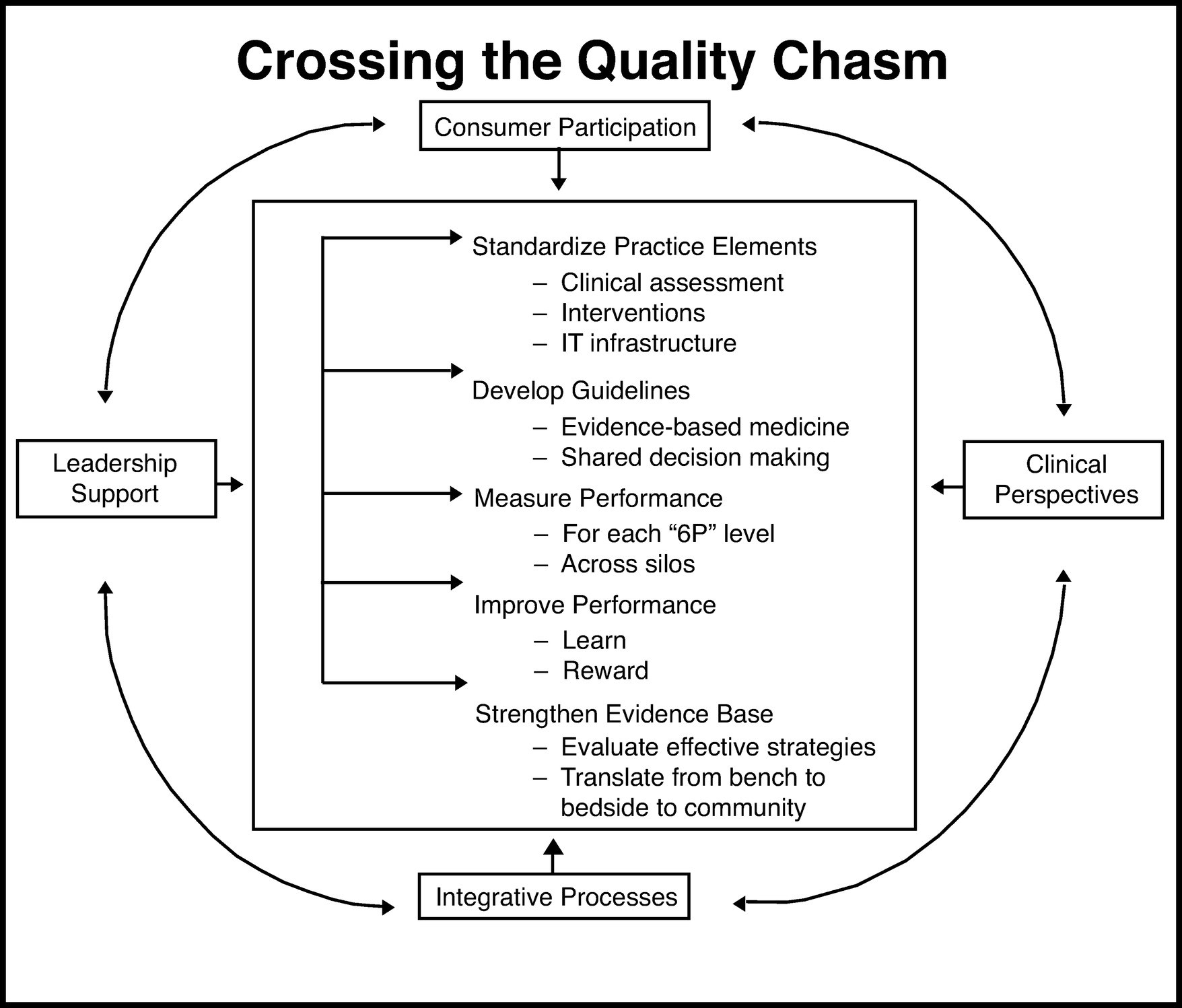

Achieve consensus and greater specificity on standard elements, methods, assessment tools, and treatment guidelines and provide applications to implement them in clinical practice using health information technology (HIT).

There is no agreement on a standard set of mental health “vital signs” or of which clinical measures to use in routine practice. Imagine seeing an internist who did not check blood pressure regularly for hypertensive care. Because this is considered a standard care expectation, something would seem amiss. Yet, what constitutes an expected mental health examination? Practice components, such as specific measures for clinical assessment, clinical decision algorithms and evidence-based interventions have not been specified and standardized in psychiatry.

Evidence-based guidelines in mental health, as developed by professional associations or other groups, will need to include measurement as an expectation with explicit guidance on which assessment tools or treatments to use for whom and when. Psychiatric treatment guidelines (

67), in part because of the current limited evidence base, are not specific and recommend that clinicians monitor treatment responses without sufficient detail about what this involves. Defining terms such as “moderate improvement” or “relapse” more specifically on a standard scale, such as a 35%–50% symptom reduction or 20% change in baseline, would reduce variability. Conservative initial parameters could be adjusted over time to reflect the growing evidence base, as is done with other chronic conditions such as hypertension, (

68) and could help determine minimal remission and recovery standards for mental disorders.

Mental health guidelines will also need to be more explicit about what constitutes adequate treatment with standardized protocols and preidentified decision points. For instance, in depression care, how long and at what dose is an adequate trial of an antidepressant before augmenting or switching? Structured guideline implementation, with clear algorithms and fidelity expectations, have been shown to improve the quality of provider performance and patient outcomes in depression care in both the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) (

49) and Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) studies (

48).

As is true in the rest of medicine, once measurement tools and clinical algorithms/guidelines are specified in mental health, they must be readily available to clinicians in a workflow-friendly way as part of EMRs, a building block of standardization. Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) built into EMRs can disseminate up-to-date clinical information required to deliver high-quality care at the point of contact. When created with user input, CDSS can facilitate incorporation of evidence-based guidelines into clinical practice. In the information age with thousands of medical journals available, keeping up on the literature on one's own is daunting. CDSS, if done correctly, can help, along with other technological aides. Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) and e-prescribing assist in minimizing errors and make it easier for clinicians to “do the right thing” (

69).

Another important potential advantage of applying HIT is the capacity to have all the necessary information about a patient's past history available at the point of care when critical decisions are made. For example, readily available information (e.g., on a secure Web site or credit card-like chip) could prevent repeat brain imaging and radiation exposure for patients presenting with psychosis in emergency department settings. In addition, easily accessible information about medication doses and laboratory findings could facilitate handoffs and minimize disruptions in care with transition between mental health providers or inpatient to outpatient psychiatry settings. At the same time, although medical information should be available when and where it is needed, it is essential that distribution of such information (and especially information related to mental health) be under the patient's control and be fully protected and secure.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) created a national agenda for HIT across medicine by designating $19 billion toward the adoption of HIT and EMRs into U.S. practice settings by 2014. In addition, physicians using a “certified” EHR, meaning it meets standards of meaningful use toward improving patient care (i.e., not for billing alone), are eligible for substantial incentives as of 2011 (

70). A report released in January 2011 showed that 41% of all office-based physicians across specialties and 80% of the nation's hospitals intend to take advantage of federal incentive payments for adoption of certified EMRs (

71). Unfortunately, nonphysician mental health providers and mental health and substance use clinical organizations were excluded from receiving the ARRA incentive payments. Mental health will need to be fully integrated into this information infrastructure.