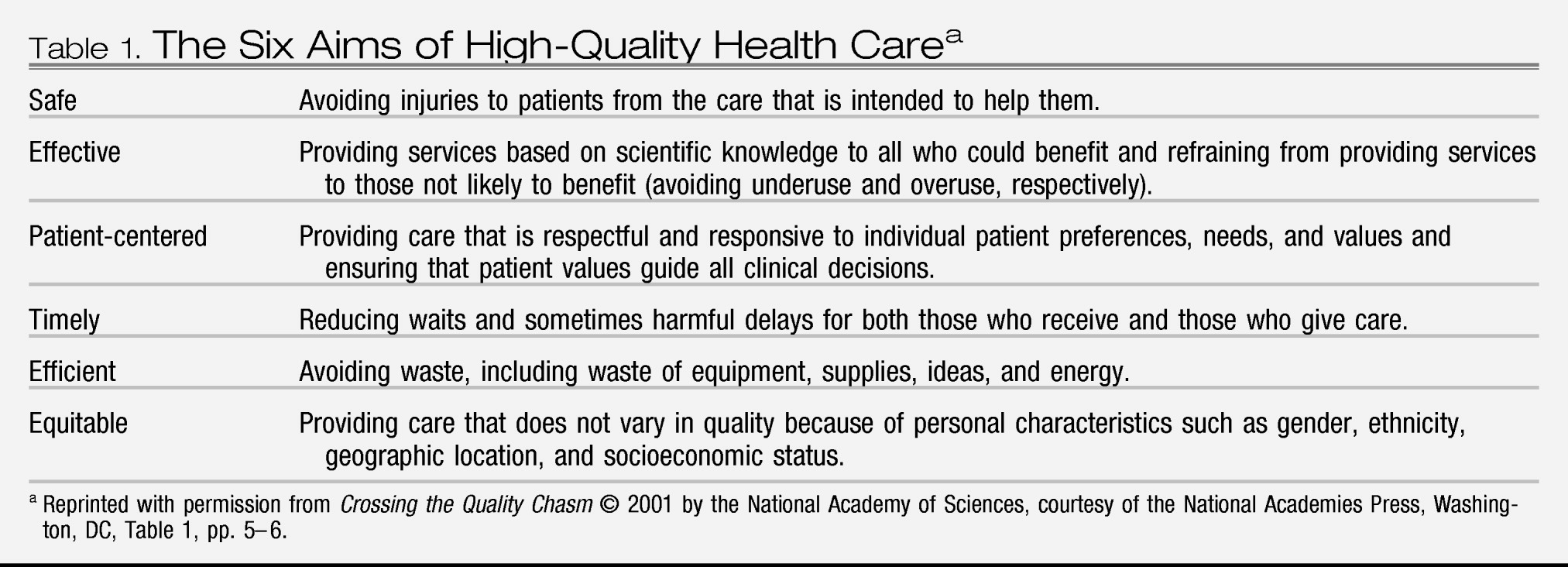

Pursue patient-centered care

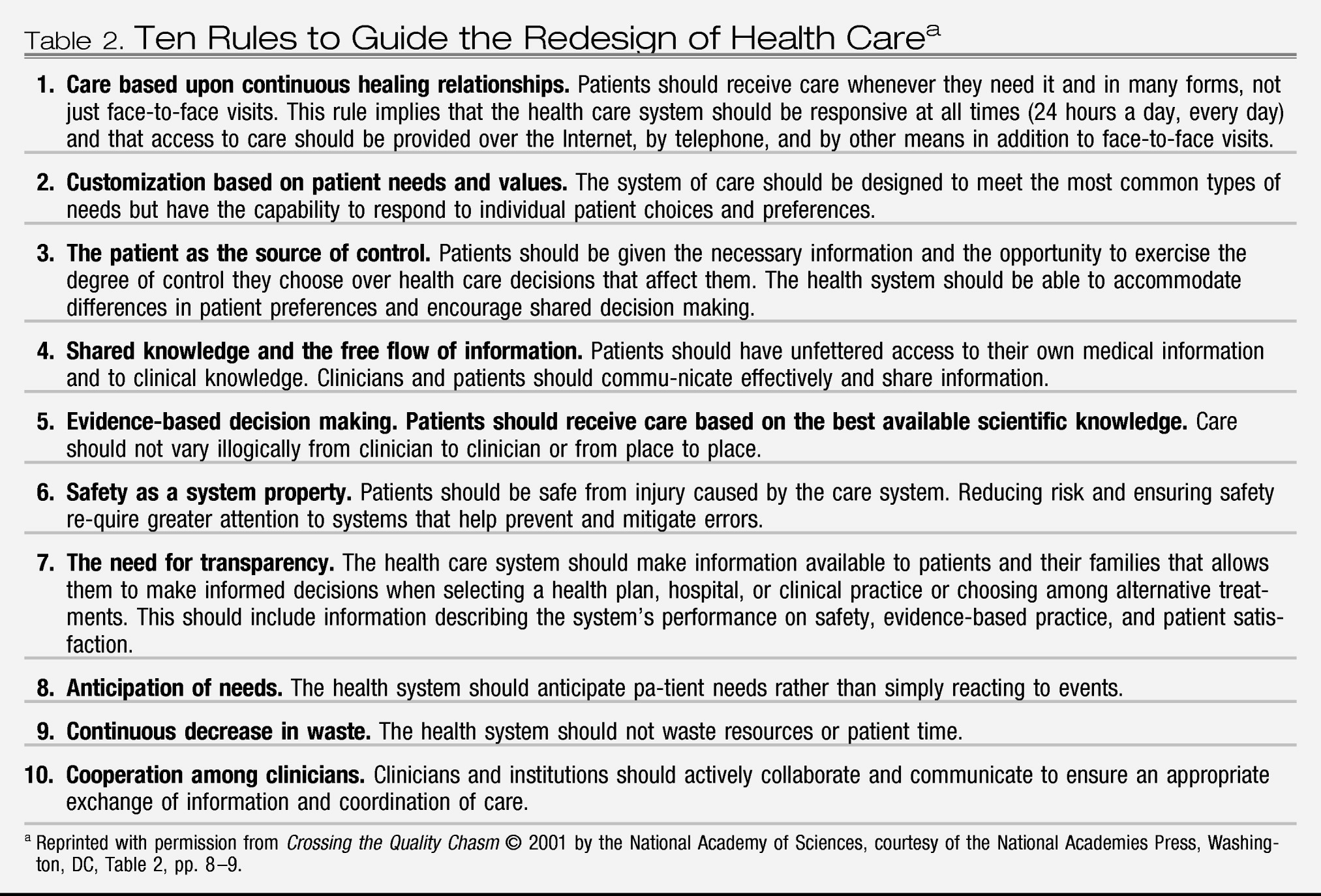

The original quality chasm report calls for “patient-centered” care (i.e., care in which patient preferences, needs, and values guide all clinical decision making; patient needs are anticipated; knowledge and information are shared freely; and care is transparent to the patient). Within a shared decision-making model, patients, as the “source of control,” should be able to exercise the degree of control they choose over health care decisions that affect them.

However, mental and substance use health care consumers face obstacles to serving as the source of control that generally are not encountered by consumers of general health care. The capacity of individuals with mental and substance use conditions to make decisions on their own behalf is often underestimated by clinicians and not supported by the health care system, especially when patients are coerced into treatment (as are the majority of individuals receiving treatment for substance use). Although a minority of mental and substance use patients, like patients with general health conditions, have some degree of impaired decision making, the adverse effect of stigma on mental and substance use patients' ability to exercise their capacity for decision making can seriously impede their ability to manage their illnesses and achieve recovery.

Clinicians and organizations providing mental and substance use health care can promote patient-centered care by 1) endorsing and supporting decision making by mental and substance use health care consumers as the default policy in their practices, 2) providing decision-making support to all such patients, including those coerced into care, and 3) supporting illness self-management practices for all consumers and formal self-management programs for individuals with chronic illnesses. Organizations delivering care additionally should involve mental and substance use health care consumers in the design, administration, and delivery of organization services.

Endorsing and supporting patient decision making means assuming each patient's right to make treatment decisions unless there is evidence of danger to the patient or others or the patient has been determined to be incompetent to make decisions. However, patient-centered decision making is also part of shared clinician-patient decision making; it does not mean that professionals must agree with all of the patient's decisions.

The original quality chasm report notes that among all consumers, there can sometimes be a tension between providing patient-centered care and providing effective (evidence-based) care. This tension was addressed in the committee's analysis as well. The committee noted that patients may express a preference for treatment that lacks an evidence base (e.g., psychodynamic psychotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder) when other, evidence-based treatments exist (e.g., medications and cognitive behavior therapy). For clinicians to adhere in such cases to an approach grounded in empirical research may leave them at odds with patients who desire an intervention that they believe will better meet their needs. In such instances, resolution may be obtained only over time, as the patient and clinician work together to reconcile competing and conflicting aims through shared decision making.

When patients, such as individuals with severe mental illnesses, propose a course of action that the clinician believes to be misguided, the clinician needs to support the patient through disagreements about treatment decisions, asking about the patient's goals for recovery, and factoring these into treatment decisions and recovery plans. Patient education can play a critical role in this process, as clinicians provide information about the benefits and risks of different treatment options. Supporting consumer decision making also means offering consumers a choice of treatments and providers; assistance in making choices; and, for individuals with significantly impaired cognition or diminished self-efficacy beliefs, compensatory mechanisms such as peer support programs and advance directives. Duke University's Program on Advance Psychiatric Directives provides toolkits and user-friendly instructions for consumers, clinicians, and family members to use in completing psychiatric advance directives (

21).

Illness self-management encompasses the day-to-day tasks an individual carries out to live successfully with chronic illness(es) and requires such skills as monitoring symptoms, using medications appropriately, practicing behaviors conducive to good health (e.g., in nutrition, sleep, and exercise), employing stress-reduction practices and managing negative emotions, using community resources appropriately, communicating effectively with health care providers, and practicing health-related problem solving and decision making (

2). Illness self-management programs for a variety of chronic illnesses, including heart disease, lung disease, stroke, and arthritis, have reduced disability, decreased needed visits to physicians and emergency rooms, and increased self-reported energy and health. Components of illness self-management for individuals with chronic mental illnesses include psychoeducation, behavioral practices to support taking medications appropriately, relapse prevention, and teaching coping skills and actions to alleviate symptoms. Stanford University has validated a standardized approach for illness self-management (described at

http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html) (

22).

Help strengthen the quality measurement and improvement infrastructure

The infrastructure needed to measure, analyze, publicly report, and improve the quality of mental and substance use health care is less well developed than that for general health care. Strengthening this infrastructure requires 1) a more coordinated strategy for filling gaps in the evidence base, 2) better dissemination of evidence to clinicians, 3) improved diagnostic and assessment strategies, 4) a stronger infrastructure for measuring and reporting quality, and 5) support for quality improvement practices at the locus of care.

Although the majority of the report's recommendations for building this infrastructure call for action by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, funders of research, and other organizations, the report identifies two key roles that individual clinicians and provider organizations need to play: 1) increasing their use of valid and reliable questionnaires or other patient-assessment instruments to assess outcomes of treatment and help build the evidence base on effective treatments and 2) using measures of processes and outcomes of care to continuously improve the quality of the care.

In general health care, patients are increasingly recognized as valid judges of the quality of care they receive. Patient questionnaires about the extent to which symptoms are reduced as a result of treatment are already being used to measure outcomes for treatment of conditions such as benign prostatic hypertrophy and cataracts. These questionnaires yield accurate and reliable information on changes in symptoms and detailed and sensitive measures of treatment effectiveness (

23). The committee recommended that outcomes of mental and substance use health care be similarly measured. In addition to reporting on experiences with care delivery, such as the extent to which they were able to participate in treatment and other care decisions and gain skill in self-management of their illness, consumers can provide information on the effectiveness of treatment in reducing symptoms and improving functioning.

Several clinically feasible, valid, and reliable questionnaires, such as the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (

24), the Patient Health Questionnaire (

25), and the Addiction Severity Index (

26,

27), can measure patient reports of symptoms and functioning. Alternatively, clinicians can assess response to treatment by obtaining information from the patient, combined with other data, and following up over time by using such instruments as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. The Veterans Health Administration requires all mental health inpatients to be rated at discharge using the GAF scale and all outpatients to be similarly rated at least once every 90 days during active treatment (

28).

Successful quality improvement also requires that such measurement be linked with day-to-day activities at the locus of care. Five practices are essential to successfully undertaking and sustaining improvements in quality: 1) ongoing communication about the desired change with those who are to affect it, 2) training in the new practice, 3) worker involvement in designing the change process, 4) sustained attention to progress in making the change, and 5) use of mechanisms for measurement, feedback, and redesign. These practices are found in leading health care quality improvement initiatives, such as those of the Institute for Health Care Improvement (

http://www.ihi.org/ihi/programs). They also have been employed by some of the smallest and least resource-rich health care providers-providers of substance use treatment services through the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (

http://www.niatx.org). Individual clinicians not already experienced in quality improvement techniques must take steps to become educated in these and incorporate them into their daily practice.

Use effective linkage mechanisms

Despite high rates (15%–60%) of co-occurrence of mental and substance use conditions (

29–

31) with multiple general health care conditions (

32), mental and substance use health services remain typically separated from each other and from general health care. These disconnected care delivery arrangements require multiple provider “handoffs” of patients for different services and the transmission of information to and joint planning by all of these providers, organizations, and agencies. The situation is exacerbated by the special legal and organizational prohibitions related to sharing mental and substance use information across providers. The Institute of Medicine calls on clinicians to routinely use four practices to bridge the separations between providers: screening, anticipating comorbidity and preplanning the clinical responses to it, establishing clinically effective linkages with other providers treating the patient, and routinely sharing information.

Effective screening can be performed by using a number of available and reliable instruments, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire, a self-administered instrument for screening for depression, anxiety disorders, alcohol abuse, and somatoform and eating disorders (

33). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism also has developed a single-question screener (one for men, one for women) for detecting alcohol problems in primary care and other settings (

34).

Because co-occurring disorders are expected in substance use and mental health treatment systems, the report recommends that whenever a patient is seen with a mental or substance use condition, the clinician should automatically screen for the other. Clinicians also should preplan their responses, i.e., treatment or referral, and whenever referral is planned, formal prearrangements with referral providers should be established. These arrangements should consist of

clinically effective linkages with other treating providers; referral by itself is not an effective coordination mechanism. The committee noted special concerns regarding linkages between mental and substance use providers and general medical providers going in both directions, i.e., individuals with mental health and substance use problems who are seen in general medical settings and individuals with severe mental illnesses and substance abuse seen in specialty behavioral health settings who also have significant general medical conditions (

35–

37). A continuum of four evidence-based coordination mechanisms are promoted, ranging from 1) formal (i.e., written) agreements among mental, substance use, and primary health care providers (less effective) to 2) case management of mental, substance use, and primary health care to 3) co-location of mental, substance-use, and primary health services and then to 4) delivery of mental, substance use, and primary health care through clinically integrated practices of primary and mental and substance use care providers (most effective). Shared electronic health records are also identified as an effective tool for care coordination.

Clinically effective linkages also require routine sharing (with patient knowledge and consent) of information on patients' problems and treatments among providers treating the patient. Committee members identified this as another issue that brings conflicting ethical and clinical imperatives into play. Identifiable information about mental health and substance abuse treatment may be particularly sensitive, in part because of the lingering stigma of these disorders. Health care systems that fail to offer patients an adequate level of privacy protection may discourage them from seeking care or being open about the problems that have brought them to treatment. However, failure to share patient-specific information across providers (e.g., allowing a patient's primary care physician to remain unaware that the patient is depressed and is receiving antidepressant medication) promotes uncoordinated and sometimes unsafe care.

The committee recognized that there is no ideal solution to this dilemma. In a patient-centered system, patients should be offered the maximum possible level of control over their health information. However, patients who are aware of the advantages of sharing at least some of their data are likely to opt for such an approach, particularly if effective technological protections for privacy are developed. Educating patients about these issues thus becomes a key strategy in promoting an optimal balance between privacy and efficient sharing of information.

Although the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act's (HIPAA)'s regulations generally permit health care organizations to release—without requiring patient consent—individually identifiable information (except psychotherapy notes) about the patient to another provider or organization for treatment purposes, the same regulations do not supersede any contrary provisions of state laws, many of which are more stringent than the HIPAA requirements. HIPAA regulations also permit health care organizations to implement their own more stringent privacy protections. Moreover, separate federal laws govern release of information pertaining to treatment received in specialty drug or alcohol use treatment programs that receive federal funding-which are also superseded by any more stringent state laws. The Institute of Medicine report calls attention to this issue as one that requires review and possible change in public policy, one that leaders in the mental and substance use should champion. Organizations that impose constraints on information sharing beyond those imposed by federal or state laws also should examine them for any unintended adverse consequences on care coordination and make appropriate changes.