Clinicians need to be informed about public quality improvement and performance measurement initiatives and play a role as early collaborators in shaping policy and application in these areas. The IOM report suggested that a performance measurement system should provide information for multiple uses, including provider-led improvement efforts, public reporting, payment and benefit design, and population health initiatives. Currently, efforts are underway to implement public reporting, performance incentivization, and professional education and engagement.

Internal versus external performance measurement

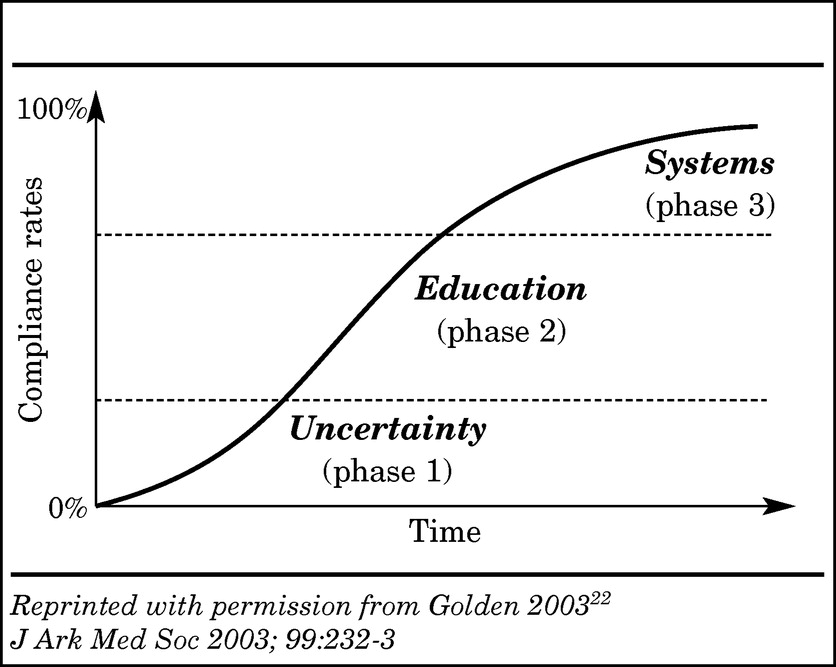

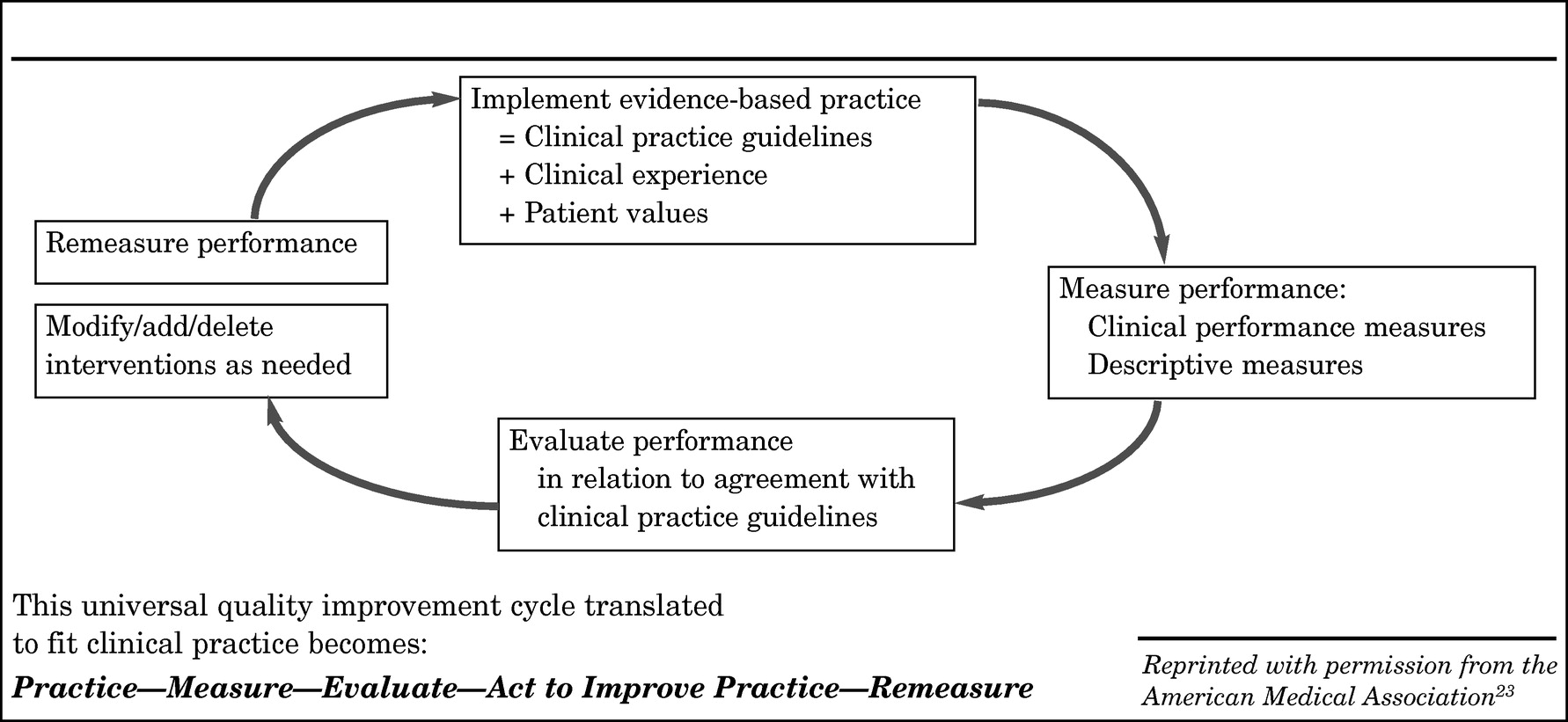

The quality improvement cycle described above (

Figure 2) involves internal use of performance measurement within the healthcare community to study and improve quality of care. Professional commitment is the significant motivation to encourage physicians to participate in performance measurement initiatives designed to provide them with feedback comparing their performance with national benchmarks and identifying areas for improvement.

However, an important and growing external incentive for performance measurement exists in the public healthcare arena, where the stated goal is to provide objective measures of the competence of healthcare providers, persons, or organizations and their ability to deliver healthcare value, translated as high-quality care and cost-effective resource utilization. Physicians are increasingly being held accountable for the quality of care they provide, with every proposal for healthcare reform now including requirements for measuring performance. While these initiatives were initially focused on general medical-surgical specialties, this movement has rapidly spread into the field of psychiatry. Nevertheless, as reported by the IOM in 2005 (

7), the infrastructure needed to measure, analyze, and publicly report data on mental health and substance abuse care remains less well developed than that for general health care (

25).

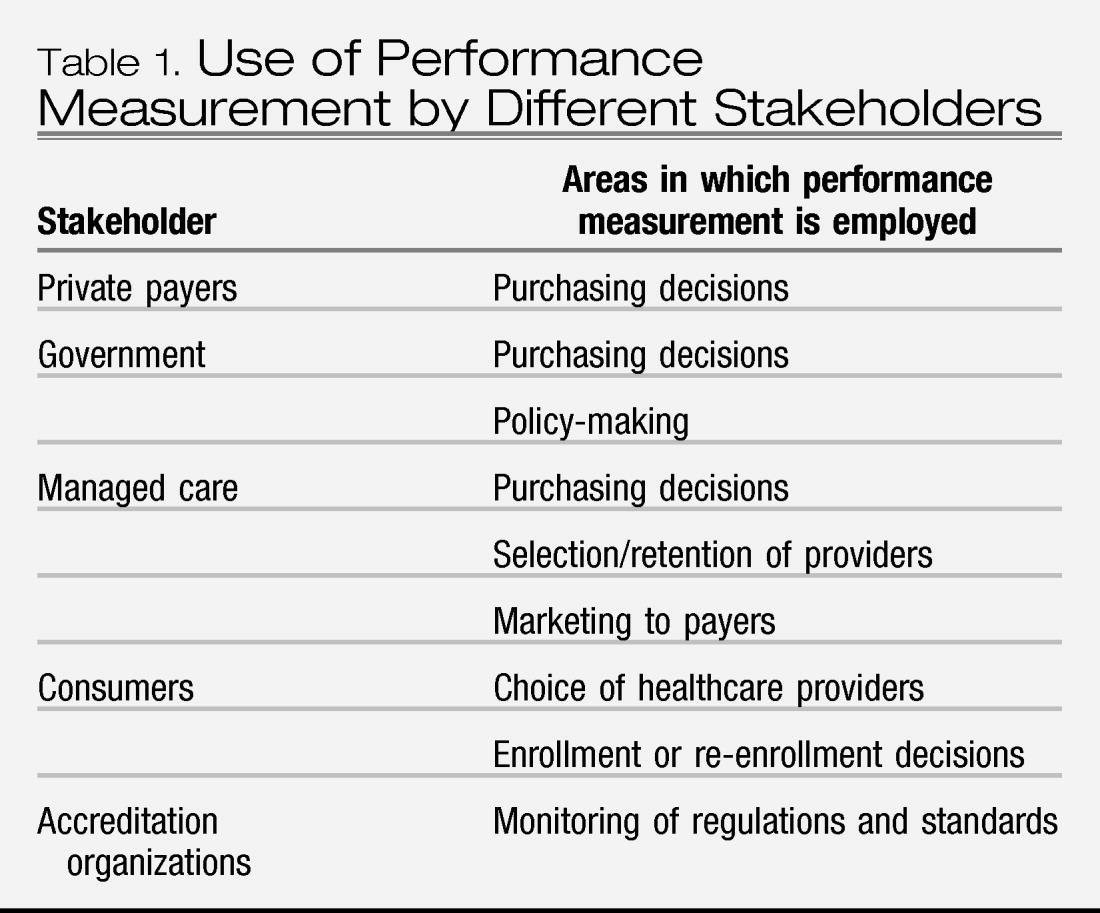

The purposes for which external performance measurement is used depend to some extent on the stakeholder involved, although the goal is always related to accountability for quality of patient care and is frequently also relevant to purchasing decisions (

Table 1). Payers for healthcare services are increasingly demanding information on the quality of the health care they are purchasing. Current initiatives are likely to lead to future requirements that physicians participate in national programs of performance measurement as a prerequisite to receiving payment or being included in approved panels. Public pressure for competency assessment has also led to professionally directed initiatives for performance measurement and QI to assure high quality care. Maintenance of certification (MOC) in many specialties requires the measurement of performance in selected clinical domains (see discussion of Board Recertification below).

Public Initiatives

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), as the cabinet level federal agency with responsibility for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has launched a significant public-private collaborative initiative to improve the quality and value of the health care delivered in this country. Based on the hypothesis that public reporting is the surest way to achieve better health care at lower cost, the Value-Driven Health Care (VDHC) Initiative aims to provide the public with information about the quality and cost of services delivered by healthcare providers (

26). This ambitious multi-year initiative will require the many stakeholders in the national healthcare system, including providers, consumers, employers, health plans, unions, government entities, and others, to work together in collaborative voluntary efforts. Participants in the VDHC Initiative commit to the following four objectives or “cornerstones” of what has also been termed “The Transparency Initiative”:

1.

Health information technology: use of health information technology standards to connect the components of the healthcare system and permit ease of communication and data exchange.

2.

Reporting on quality: measuring and reporting performance of hospitals, physicians, and other providers; providing public benchmarks and comparative information.

3.

Reporting on price: measuring and publishing price information tied to quality data in order to give the public information on the value of healthcare services.

4.

Incentives for quality and value: providing incentives for quality and value to support both those who provide and those who purchase high-quality, cost-effective care.

In 2006, President Bush signed an executive order that requires all agencies that administer federal health insurance benefits, including Medicare, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Plan, TRICARE for uniformed personnel (Department of Defense), the Indian Health Service (Health and Human Services), and any program administered under the VA, to share price and provider quality data with beneficiaries. The order also calls for similar reporting in non-federal healthcare networks in the future. This initiative, which involves a public/private partnership with agencies that are implementing quality measurement systems, is more than conceptual: 50 of the top 200 employers in the United States and at least one major labor union have signed statements of support for the initiative and the four cornerstones. Many state governments have also signed statements of support or are developing their own executive orders to implement the initiative.

The Transparency Initiative is being implemented in pilot projects in which designated contractors are aggregating and analyzing data on clinical services provided to patients with private insurance or Medicaid and Medicare coverage. Consumers, private insurers, employers, and state governments are working together using clinical performance measures to produce information that will allow beneficiaries to make more informed coverage choices. The first reports will provide expanded information for Medicare beneficiaries on the quality of service provided by Medicare providers.

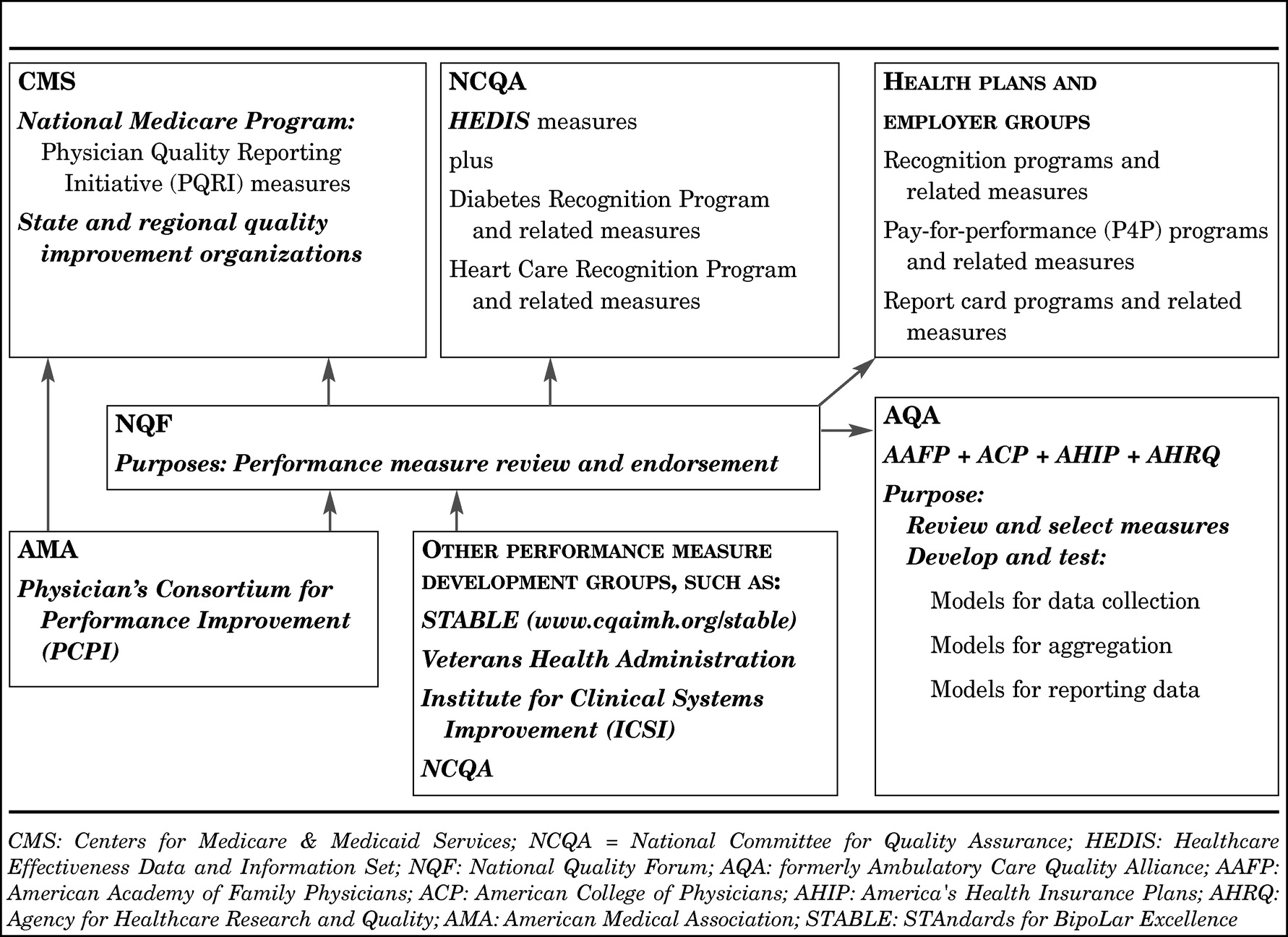

The CMS have also initiated a Quality Improvement Roadmap Initiative involving hospitals, long-term care facilities, home health agencies, and physicians' offices. As part of this initiative, CMS is working with federal and state entities, accreditation bodies, insurers, and professional societies to achieve consensus on evidence-based measures that have wide acceptability in the healthcare industry. As part of this effort, the VA, the Joint Commission (JC), the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA), the Ambulatory Care Quality Alliance (AQA), the National Quality Forum (NQF) and medical specialty societies are all actively involved in developing, endorsing, and disseminating reliable and valid performance measures based on sound clinical evidence. The American Medical Association's Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) is also a major developer of performance measures. With representation from the various specialty professional organizations, the measures are developed by physicians, for physicians. The NQF reviews and endorses measures after a thorough review of the methodology used in the measure development process. The AQA is the implementing arm, reviewing and selecting measures for inclusion in data collection, data aggregation, and data reporting efforts.

In April 2007, CMS issued a letter to State Medicaid Directors announcing a national Value-Driven Health Care (VDHC) initiative that incorporates the four “cornerstones” of the Health Care Transparency Initiative, as well as a new national Medicaid Quality Improvement Program (MQIP).

Although controversy still exists concerning the public reporting of clinical quality measures, there has been a steady increase in such reporting over the last few years, primarily at the hospital level (e.g., state initiatives, Health Quality Alliance [HQA], JC, NCQA's Health Care Effectiveness Data and Information Set [HEDIS]). In addition to providing information to the public, these programs incorporate organizational performance measures related to maintenance of accreditation status. It is hoped that such transparency will incentivize organizations and, in the future, individuals, to assess their adherence to evidence-based clinical practices and implement quality improvement activities if needed.

Payment reform and pay for performance

Reform in clinical payments is a response to the increasing use of valuable, finite clinical resources without evidence that more interventions and more spending will routinely result in better care. While many studies have reported increased medical spending that did not produce better results (

27), there is evidence that rising spending for mental health has resulted in improved access to care and overall good value as a result of expenditures for evidence-based care for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (

28). However, while, on average, mental health spending appears to be purchasing good value, there is still evidence of specific quality deficits, as evidenced by relatively low scores for depression care in the HEDIS, by the RAND Community Quality Index Study, which found that people with depression receive only 57.7% of recommended services, and a 2006 study indicating that one fifth to one fourth of spending on depression has little prospect of helping the patient (

28). Thus private payers, employers, the government, and taxpayers are all seeking greater accountability for the money being spent.

Pay for performance (P4P) involves linking physician reimbursement to the provision of quality care. The goal is to provide incentives for clinicians to adhere to evidence-based standards of care and reward clinicians who avoid overuse, underuse, and misuse of critical clinical interventions. The expected outcome of P4P initiatives is a reduction in undesirable variation as a result of providing evidence-based care along with a reduction in total spending as a result of better outcomes (e.g., fewer delays in diagnosis, fewer outpatient visits, reduced hospitalizations, fewer complications). The key to using this still controversial although increasingly widely accepted strategy is the use of valid and reliable clinical measures, feasible data collection methods, and consistent and transparent analysis and reporting mechanisms. In P4P efforts, the performance measurement system and mechanisms come from a predetermined external source (e.g., as in the Quality Improvement Roadmap Initiative from CMS). However, if quality improvement interventions are found to be necessary, it is up to the individual practitioner to identify and implement such activities. The key to clinician success in a P4P system is adoption of quality improvement strategies that result in increased use of key evidence-based clinical interventions (

29).

In 2006, Congress authorized CMS to develop a pay-for-performance initiative by 2009. In response, as part of its overall quality improvement efforts, the CMS launched the Physician Voluntary Reporting Program (PVRP); the title of the program was changed to Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) in 2007 (

30). The PQRI is a first step toward linking Medicare payments to health professionals with quality of care. The goal is to prevent chronic disease complications, avoid preventable hospitalizations, and generally improve the quality of care. When the program was launched in 2006, it incorporated a core set of 16 national consensus performance measures, selected from an overall set of 36 evidence-based clinically valid measures based on practice guidelines endorsed by physicians and medical specialty societies. During an initial period, physicians could participate in voluntary reporting and receive confidential feedback from information captured through the administrative claims system augmented with a set of special codes that provided the numerator data required for particular performance measures. Starting in July 1, 2007, eligible professionals who elected to participate in the still voluntary reporting program by providing data on a designated set of quality measures on claims for dates of service from July 1 to December 31, 2007 could earn a lump-sum bonus payment, subject to a cap of 1.5% of total allowed charges for covered Medicare physician fee schedule services. In November 2007, Congress stated that this process will continue in 2008.

In coordination with the American Medical Association's PCPI, CMS is developing measures that apply to all priority clinical conditions and specialty practices. Currently, healthcare professionals are only required to report measures applicable to services they provide to Medicare beneficiaries. In 2007, only one measure related to psychiatric care was included in the introductory set of measures: whether a patient with acute depression receives a full 12 week trial of antidepressant medication. However, an expanded set of 119 measures for 2008 was posted on November 15, 2007 in the Federal Register and on the U.S. HHS CMS website (

www.cms.hhs.gov/PQRI/15_MeasuresCodes.asp#TopOfPage). Thus, in 2008, three additional measures related to depression are now included: whether screening for depression occurs; whether patients meet DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder; and whether patients with major depressive disorder are assessed for suicide risk.

To support this public-private quality reporting initiative, a multi-faceted system is being developed that involves 1) organizations that develop performance measures; 2) an umbrella organization that reviews measures against development criteria and endorses those measures that are deemed to meet these criteria and address declared national clinical priorities; 3) organizations that develop, test, and implement models for data collection, aggregation, and reporting of selected endorsed measures; and 4) organizations that will apply the use of these measures and support systems (see

Figure 3). The implementation of this system heralds a new era in how health care will operate in the United States.

Board recertification

In 2001, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), of which the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) is a member, approved the transition to a continuous professional development program called Maintenance of Certification (MOC) by the end of 2005. In response to public concern that it was inadequate to rely on a cognitive examination alone to ensure ongoing competence of physicians, the MOC program focuses on six competencies (pa-tient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice), which are incorporated into four component categories used to recertify specialists:

•.

Part I. Professional Standing (a valid, unrestricted license)

•.

Part II. Lifelong Learning and Self-Assessment (participation in educational and self-assessment programs)

•.

Part III. Cognitive Expertise (formal examination)

•.

Part IV. Practice Performance Assessment.

The Practice Performance Assessment asks specialists to demonstrate that they can assess the quality of care they provide compared with their peers and national benchmarks and that they can, as needed, apply best evidence or consensus recommendations to improve care using follow-up assessment. Practice Performance Assessment is fundamentally a QI and performance measurement approach to ensuring high quality patient care.

The ABPN's MOC Program contains the Part IV component, which is titled Performance in Practice. Beginning in 2012, a phased-in approach will require diplomates of the ABPN to participate in a quality improvement program that includes two modules: 1) a clinical module, involving chart review, and 2) a feedback module, involving patient or peer review. The clinical module will require the clinician to use data obtained from or pertinent to a diplomate's personal clinical practice and evaluate cases in a specific diagnostic category with reference to best practice and/or practice guidelines published in the literature. The diplomate must develop an intervention plan for improving his or her performance, as necessary, and then re-assess data from another sample of cases in the same diagnostic category within 24 months.