Considering the Role of the Amygdala in Psychotic Illness: A Clinicopathological Correlation

Abstract

CASE REPORT

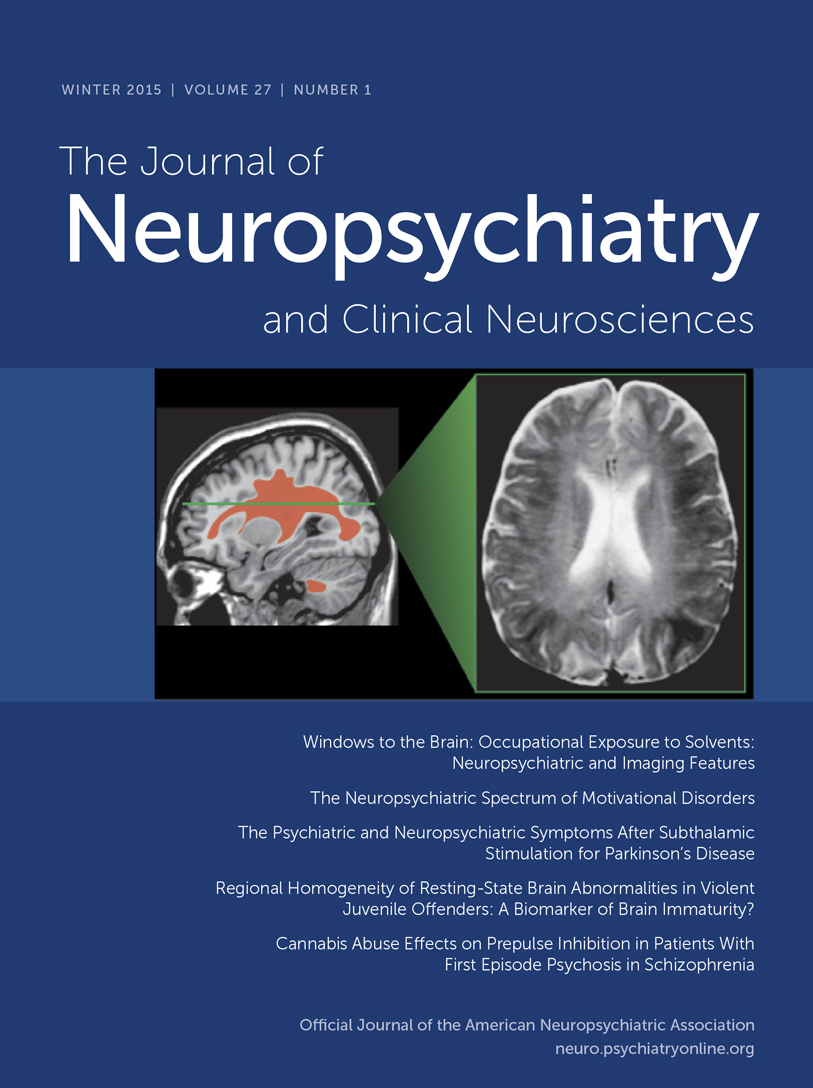

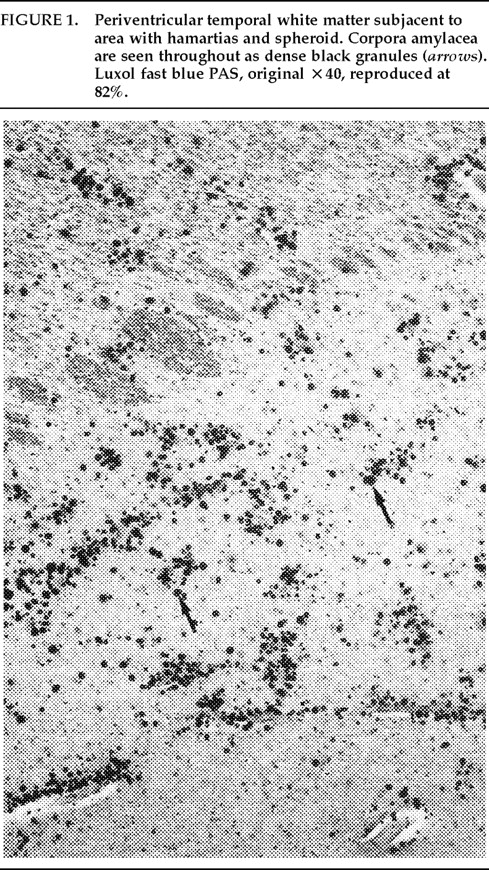

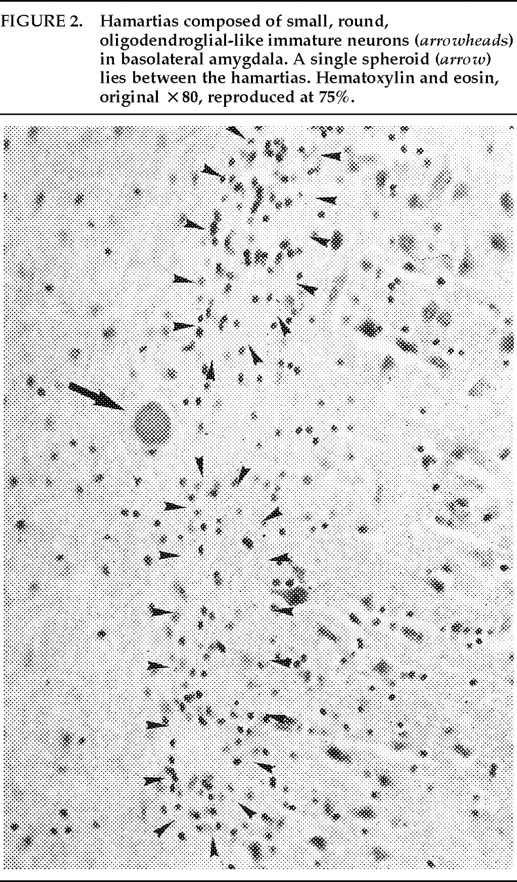

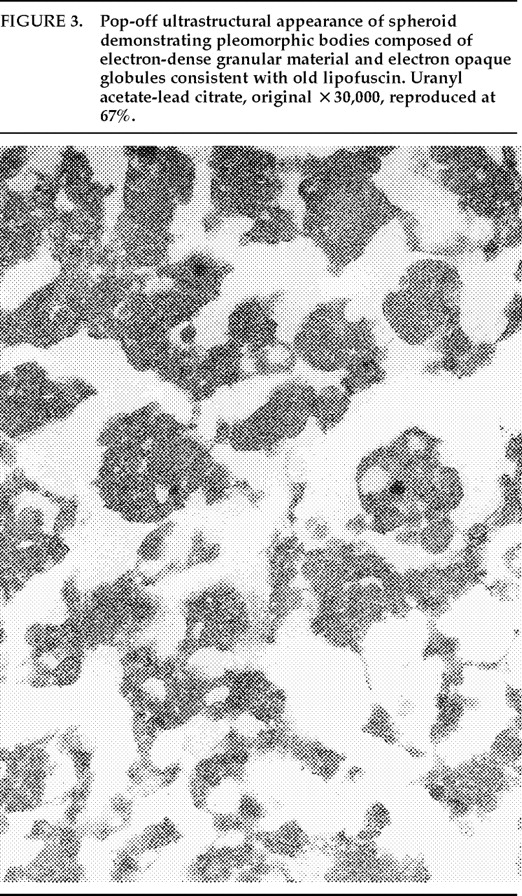

Ms. A. was first admitted to the psychiatric unit of Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester, NY, in autumn of 1979 at the age of 20. By report of her mother, she was the product of a normal gestation and normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and weighed 7 pounds at birth. There was no childhood history of high fever, seizure, or serious illness. The patient's psychiatric and medical history were unremarkable until age 15, when she sustained head trauma secondary to being kicked by a horse. There was no loss of consciousness or apparent neurological sequela related to this event. Ms. A. began considering herself a “born-again” Christian while in high school, but she did not increase her religious activity at that time. At age 18, she enrolled in the state university. She began having vivid hallucinations at that time, although these were only reported retrospectively. Her parents became concerned about her affiliation with a cult-like church. During the second semester of her freshman year, Ms. A. dropped out of college because of her fears of the occult, involving, in particular, the idea that a professor was trying to hypnotize her. At home, she had delusions of influence, accusing her father of hypnotizing her. She described unusual thoughts to her mother—for example, the ideas that demons were in her bedroom and that acquaintances were controlling her. Although the patient was employed during this time, she was hyperreligious, reciting the Bible frequently and sending money to a faith-healing church.In summer 1979, slightly more than one year after dropping out of college, Ms. A. poured boiling water on her leg, saying she was being compelled to do this by forces outside her control, and a week later she bought “health food” for her leg. Two months afterward she was admitted to a local hospital and evaluated for a week. Her diagnosis at that time was chronic paranoid schizophrenia, and she was begun on low-dose trifluoperazine. Nine days after discharge, Ms. A. presented to the emergency department of another hospital with apparent disorientation, confusion, and fluctuating levels of consciousness. The patient uttered repetitive sentences, such as “Wake me up,” and held the cross she wore up in the air. During the ensuing months she continued to hallucinate. She stopped her medication a month after the hospital evaluation. Two months later, Ms. A. amputated the distal third of her tongue in response to commands from inner voices. She said she had felt “overcome” by “demonic forces” and “forced downstairs by air cushions.” Using a pillow to stop the bleeding, she called 911 emergency services. After surgical reattachment of the tongue fragment, the patient was admitted to the Department of Psychiatry at Strong Memorial Hospital for 3 months. While hospitalized, she revealed complex violent sexual hallucinations (including visual hallucinations of being “raped by Prince Charles”) in addition to other symptomatology. It was noted that psychosis seemed to be exacerbated perimenstrually.Results of physical and neurological examinations conducted during this hospital stay were unremarkable. Lumbar puncture was performed, and cerebral spinal fluid studies for glucose, protein, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), viral titers, bacterial cultures, and immunoglobulin G were all normal. Neuropsychological testing was within normal limits. A positive serum RPR with negative fluorescent treponemal antibody test prompted autoimmune workup. Autoimmune studies were as follows: initial antinuclear antibody test (ANA) positive at 1:1,000 dilution, speckled pattern, elevated hemolytic complement (CH50) of 114, and elevated immunoglobulin M (462%) on electrophoresis. Cryoglobulins, Raye cell test, C1q, rheumatoid factor, and skin biopsy for systemic lupus erythematosus were all negative. Serial erythrocyte sedimentation rates were 43, 16, 25, and 10. A repeat ANA 1 week after the initial result was trace positive at 1:1,000 dilution. Clinically, the patient did not meet criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus or any other autoimmune disorder. The differential diagnosis was “atypical psychosis” versus temporal lobe epilepsy. Sequential, sustained trials with adequate doses of carbamazepine, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and molindone were not successful.Over the next 13 years, Ms. A. had eight acute inpatient hospitalizations and three lengthy admissions on the teaching service at the local state hospital (totaling 79 months) for exacerbations of psychosis and suicidal ideations, often bizarre in nature. In addition to the medications listed above, she received thorough therapeutic trials of diazepam, flurazepam, lithium, valproic acid, phenelzine, thiothixene, phenytoin, lorazepam, clonazepam, thioridazine, amitriptyline/perphenazine (Triavil), perphenazine, fluphenazine, fluoxetine, and bupropion, with little success. Numerous psychotherapeutic interventions were tried, including insight-oriented psychotherapy, amobarbital interview and hypnosis, behavioral modification, supportive therapy with a psychoeducational focus, family therapy, and various supportive residential and occupational placements. In total, 16 EEG studies were done; 4 revealed paroxysmal bilateral spike and wave activity, and the rest were within normal limits. CT and MRI studies performed during this period inconsistently showed temporal asymmetry (R>L).Ms. A.'s only persistent medical issue was periodic flares of genital herpes. Five years after her initial psychiatric diagnosis, she was noted to have a fluctuating neutropenia not associated with medication (white blood count 2,100–8,400) and mild anemia (hematocrit ranging from 34 to >40). Thyroid functions were normal until 1992, when thyroid-stimulating hormone was slightly elevated to 11.08, with a subsequent normal value 2 weeks later. ANA titers were often normal and occasionally weakly positive (1:160).Although Ms. A. suffered a chronically deteriorating clinical course, with persistent hallucinations and the belief that she was being controlled or hypnotized, she was noted to retain much of her affective tone, and she engaged with staff and fellow patients. Her thought processing was generally lucid, although there was formal thought disorder during periods of psychotic exacerbation. Repeated neuropsychologic testing showed a general decline in intellectual function. Increasingly poor performance on tests of concentration and attention made it difficult to interpret tests of other functions such as verbal fluency and short-term memory.Ms. A.'s discharge from her last psychiatric hospitalization was in late 1992. She was taking lithium 900 mg qd and haloperidol 15 mg qd in divided doses, and fluoxetine 20 mg qd. During this hospitalization, she had received a diagnosis of mild sleep apnea. Two weeks later, the patient developed a sore throat, confusion, and slurred speech. After several evaluations in the emergency department, she was admitted to the Medicine Service of Strong Memorial Hospital with stridorous breathing, progressive hyponatremia (sodium values declining from 135 to 130 to 123 in the three days prior to admission), and complaints of chest pain. She had remained on the above medications, and her lithium level was 0.46 two days prior to admission. She expired precipitously early on the morning of the day after admission. No cause of death was established, despite an autopsy and toxicological tests (Office of the Medical Examiner, Monroe County, NY) and case review by the faculty of the Department of Medicine, by outside consultants, and by the State Department of Health.Pathologic findings. The postmortem examination (autopsy) did not reveal an anatomic cause of death. From the available clinical, laboratory, and pathologic data, it appeared that the patient died of a toxic-metabolic process in which drug therapy, hyponatremia, and hypothyroidism may have played some role. The systemic autopsy findings were confined to some acute lung and gastrointestinal tract congestion and thyroid lesions. The thyroid gland showed lobulations due to fibrosis and infiltration by lymphocytes, with Hürthle cell metaplasia of follicular epithelium. There was also a small focus of papillary carcinoma. The pituitary was enlarged as a result of thyrotroph cell hyperplasia. Small numbers of lymphocytes were also found in the pericardium. These findings were consistent with an active systemic infection, perhaps viral, or may have reflected some immune reaction. However, neither infection nor immune reaction could be established, and such diagnostic possibilities remain speculative.Of more specific interest were those lesions found in the central nervous system. The brain demonstrated diffuse, mild cerebral edema with some uncal grooving. Microscopically, mild intramyelinic edema was observed in the myelinated fibers of pons, internal capsule, and frontal white matter. These alterations were consistent with an acute toxic-metabolic process in which fluid and, probably, small ions accumulate between the myelin lamellae because of osmotic shifts; such a process has been reported in central pontine myelinolysis.9 There was also a mild and chronic lymphocytic perivasculitis of the cingulate, left occipital and right superior posterior temporal cortex, left amygdala, pons, and posterior pituitary. Neither demyelination nor necrosis was associated with this perivasculitis. One could speculate that these findings reflect a chronic infectious process that could have played a role in the patient's illness. Alternatively, they may be more consistent with an epiphenomenon in the form of an acute viral infection or active immunologic response to an unknown, noninfectious antigen. Such inflammatory infiltrates are occasionally seen at autopsy in patients without neurologic or psychiatric disease.The most noteworthy lesion with respect to the patient's psychiatric illness, however, was found in the left amygdala region. There were no specific asymmetries appreciated grossly in the temporal lobe. Microscopically, however, there was a focal decrease in myelinated fibers and replacement by fibrillary astrogliosis (scarring) with corpora amylacea in the left temporal white matter (Figure 1) adjacent to the basolateral portion of the amygdaloid complex.In addition, within the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala, there were two small hamartias, or regions of microdysgenesis. In these areas, primitive or germinal cells were admixed with large pyramidal cells. The hamartias consisted of clusters of round nuclei, often with a prominent hematoxylinophilic nucleolus, surrounded by a perinuclear clear space (Figure 2). The hamartias were so small that they could be seen in only a few serial sections. The Luxol fast blue PAS–stained section was decolorized and immunostained with an antibody to bcl-2, a marker of immature developing neurons (processed by Dr. Anthony Yachnis, University of Florida).10 The cells did not label, but this was interpreted as a false negative stain. Positive immunostaining is obtained only with freshly cut sections (A. T. Yachnis, personal communication). This particular section had been stained and stored for 3 years before we consulted Dr. Yachnis regarding this technique. The specificity of the hamartias was confirmed by their absence in the corresponding levels of the contralateral (right) amygdala and in an additional 20 control amygdalas at the same level.Within the area of the hamartias, there also was a single swollen eosinophilic structure, which most likely represents a neuraxonal spheroid or swelling (Figure 2). Spheroids most commonly occur following brain trauma, in which they have been referred to as shearing injuries.11 This structure was examined ultrastructurally by using the pop-off technique.12 Ultrastructural preservation was understandably poor but revealed an accumulation of fairly uniform structures most consistent with residual lysosomal autophagic bodies (Figure 3). Such reactive axonal spheroids are consistent with remote destructive processes such as trauma.The remaining sections of the central nervous system were essentially unremarkable except for a small cortical hamartia in layer 3 of the right occipital cortex. This lesion consisted of a cluster of ill-defined neuroglial cells that also was so small that it was lost in serial sections and could not be studied further.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

DISCUSSION

Lesion Studies

Stimulation Studies

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Psychosis

Role of the Amygdala in TLE

Clinical Correlation

Neuropathologic Correlates of TLE and Schizophrenia

Neuropathologic Correlates

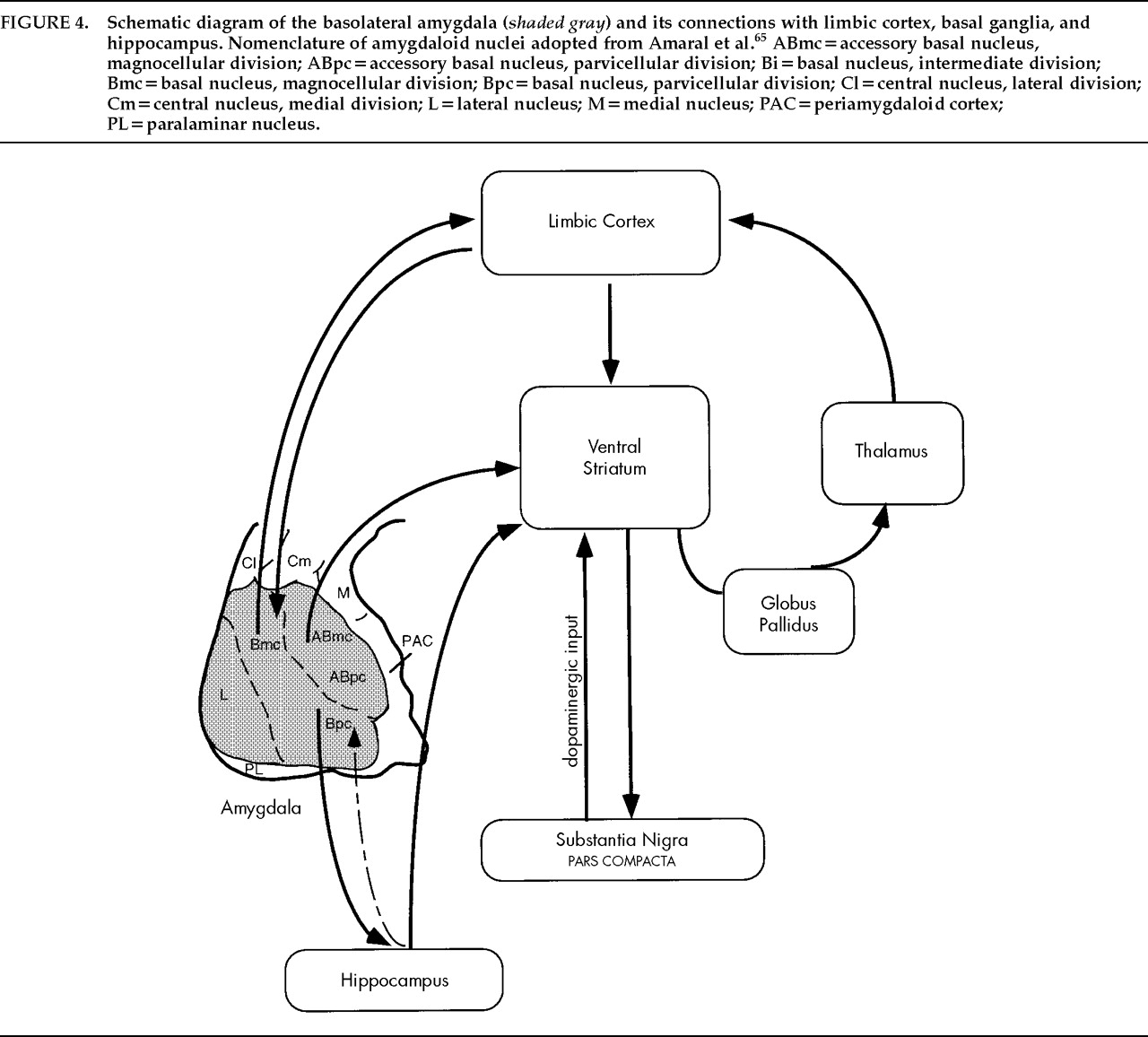

Anatomic Features of the Basolateral Nuclear Group

Pathways and Connections

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).