Conversion disorder, in which symptoms suggest a physical disorder but result from psychological factors, is common.

1 The term

conversion disorder reflects the hypothesis that an unconscious psychological conflict is “converted” into symbolic somatic symptoms, thereby reducing anxiety and shielding the conscious self from a painful emotion. The pathogenesis of conversion symptoms is controversial, although most patients are considered to derive primary or secondary gain. In many cases the mechanism underlying conversion symptoms is never identified. In many other cases the psychological mechanism, or provocative factor, is speculative. Whether or not an emotional stressor or motivation is identified, many patients fail to follow through with, or benefit from, psychological or psychiatric intervention.

A number of pitfalls confront efforts to differentiate organic and conversion disorders.

2 Reliance on isolated clinical features is often unwise. Conversion disorder is usually diagnosed after the history, physical examination, and laboratory studies fail to disclose an organic etiology—but positive evidence of a psychological etiology should be sought.

2 Nonepileptic seizures are common, occurring in about 15% of all conversion patients and 15% to 25% of admissions to epilepsy monitoring units.

3 Sexual and physical abuse, motor vehicle or work-related injury, or a major life stress is often identified as the precipitating factor.

3–6Conversion symptoms more often afflict the left half of the body,

7–10 suggesting that cerebral dysfunction, if identified, may be more frequent in the right (nondominant) hemisphere. Although conversion symptoms are well described in patients with neurologic disorders such as epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis,

2,11–13 we were unable to find prior studies examining the possible association between lateralized cerebral dysfunction and conversion disorder.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between lateralization of cerebral dysfunction and conversion disorder in patients with conversion nonepileptic seizures (C-NES) and unilateral cerebral structural or electroencephalographic abnormalities. Proportions of patients with left- versus right-sided abnormalities were compared to those found among patients with epilepsy only and epilepsy plus psychiatric disorders other than conversion disorder.

METHODS

Among 311 patients given diagnoses of C-NES (with or without concurrent epilepsy) at our comprehensive epilepsy center between 1990 and 1998, we identified 79 patients with documented cerebral structural or electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities (bilateral, left-sided, or right-sided). Comparison groups consisted of 51 patients with epilepsy only (without C-NES or any other psychiatric disorders) and 71 patients with epilepsy and other psychiatric disorders. Comparison group patients were all adult patients who presented at our weekly epilepsy presurgical conference over a two-year period. All patients underwent detailed history and physical and neurologic examination by an epileptologist. All patients with C-NES or other psychiatric disorders were evaluated by a neuropsychiatrist (K.A.) who conducted the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, patient version. Of the C-NES patients with cerebral abnormalities, 55 (70%) had neuropsychological testing. In the non-C-NES groups, 79 patients (65%) had neuropsychological testing.

Conversion disorder was diagnosed in all patients by both a neurologist and a neuropsychiatrist. The diagnosis was based on the presence of symptoms that suggested a neurological disorder (e.g., seizures or weakness) but were found to have a psychological basis. One or more of the patients' typical episodes were recorded on video-EEG. In all cases, clinical and laboratory studies failed to support a neurologic etiology for the specific symptom, and positive evidence for a psychological etiology (e.g., elicitation or abatement of symptoms with suggestion) was found. No patient had evidence of intentional symptom production. C-NES was diagnosed only if a typical spell was recorded on video-EEG and no ictal electrographic changes of cerebral origin were observed. Recorded episodes could be spontaneous, provoked by suggestive techniques, or both. If possible ictal EEG changes were obscured by muscle and movement artifact, then computer filtering was done to eliminate as much artifact as possible. These episodes had to be clinically and electrographically distinct from epileptic seizures and not consistent with forms of epilepsy such as simple partial seizures (e.g., subjective symptoms only) or frontal lobe complex partial seizures (e.g., stereotypic brief episodes of similar duration), which often are not accompanied by scalp-EEG changes. Ambiguous cases were excluded from the study.

C-NES was distinguished from other nonconversion psychiatric disorders with paroxysmal features, such as panic disorder, by using the definition of C-NES previously described.

3 Paroxysmal behavioral events explainable by a psychiatric disorder other than conversion, such as panic, psychotic disorders, or impulse control disorders, were excluded. Patients received a diagnosis of conversion NES if they met DSM-III-R criteria for Conversion Disorder or if they manifested NES as a conversion symptom in the context of Somatoform Disorder.

Laterality was determined by either structural or physiological abnormalities. Structural cortical or subcortical lesions were diagnosed by a neuroradiologist on the basis of MRI or CT studies in all patients. Patients with prior brain surgery were included. The diagnosis of EEG abnormality was made by a board-certified electroencephalographer and consisted of definite interictal or ictal epileptiform activity or focal slowing on at least two recordings. Intracarotid sodium amobarbital (Wada) tests were performed in patients who were considered candidates for focal resective brain surgery. A total of 7 patients were recoded as to laterality based on the results of Wada test for language dominance. Specifically, 5 patients were switched from left to right and 2 from right to left dominance. Six of the 7 patients were in the comparison groups, not in the C-NES groups.

RESULTS

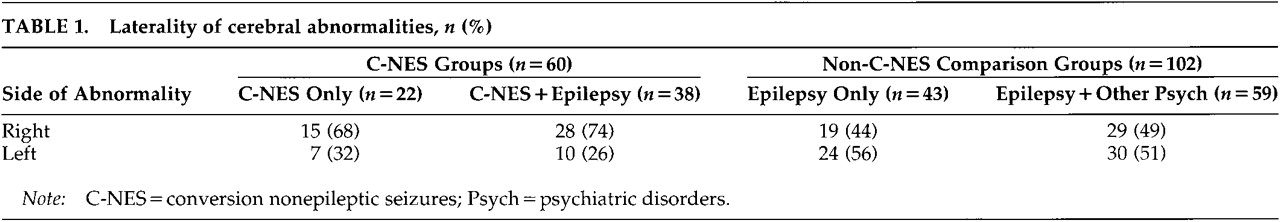

We identified three groups of patients: one NES group (consisting of two subgroups, NES only and NES plus epilepsy) and two epilepsy comparison groups (epilepsy only and epilepsy plus other psychiatric disorders). The comparison group of patients with epilepsy plus psychiatric disorders did not include patients with C-NES. First we identified all patients with C-NES and any type of structural or physiological abnormalities (

n=79). Of these, 60 had evidence of unilateral cerebral dysfunction. These represent our C-NES group. Of these 60 patients, 22 had C-NES only and 38 had C-NES plus epilepsy. We identified 102 patients with unilateral abnormalities for our two comparisons groups. Forty-three had epilepsy only and evidence of unilateral dysfunction, and 59 had epilepsy plus psychiatric disorders other than conversion and clear unilateral signs. Laterality of the cerebral abnormalities for all groups is described in

Table 1.

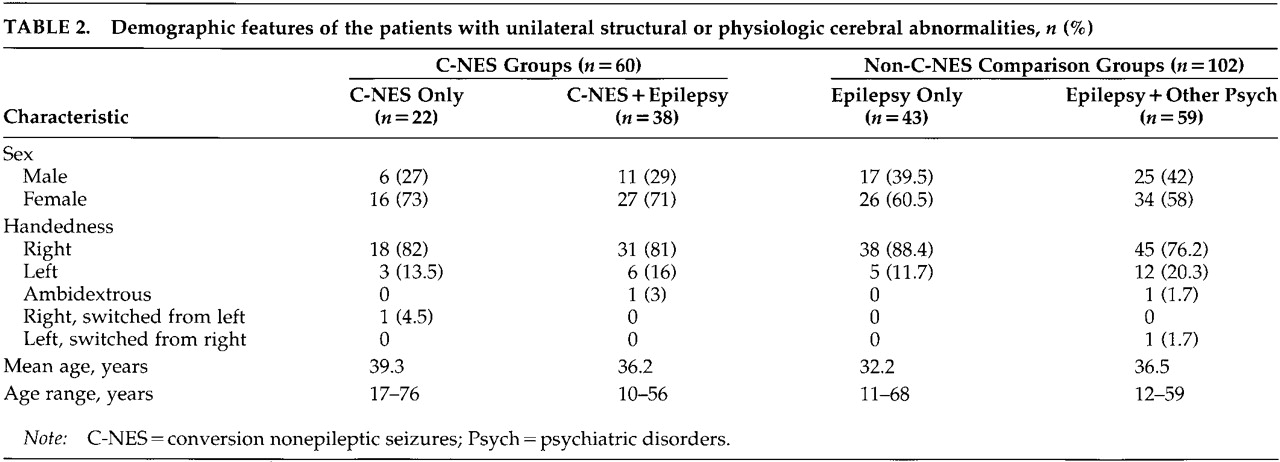

The demographic and clinical features of all patients with unilateral abnormalities are summarized in

Table 2 and

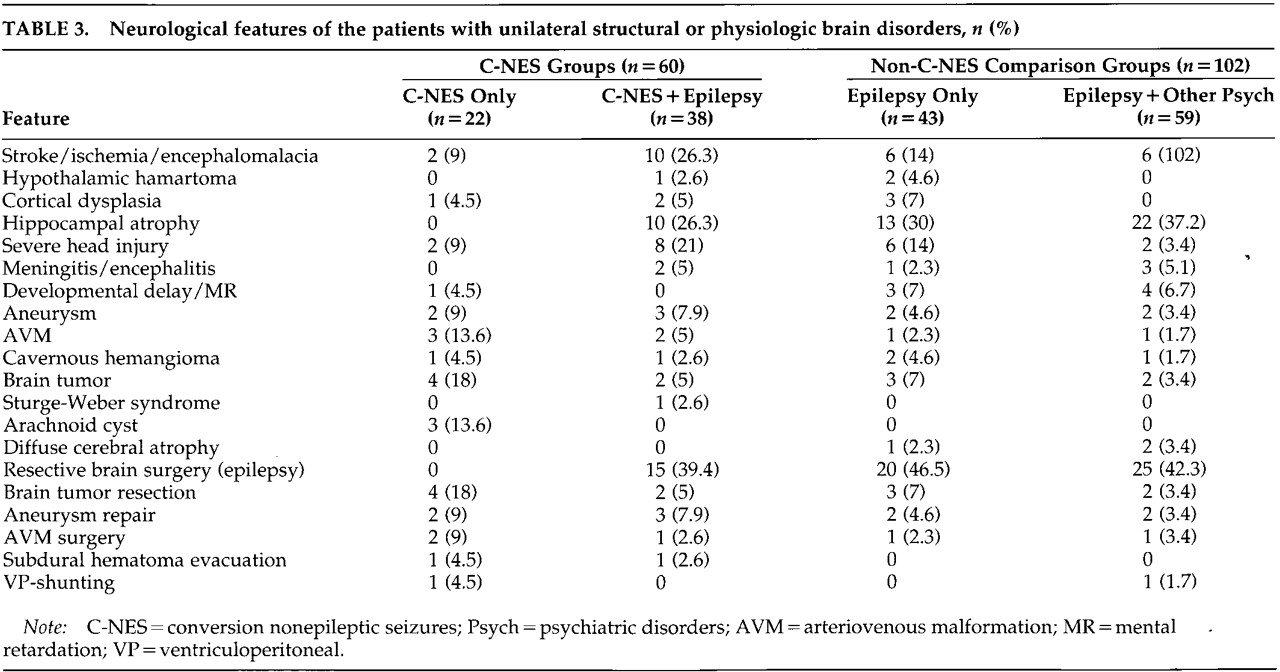

Table 3. Past neurologic histories for both the C-NES and comparison groups include head trauma, CNS infection, perinatal injury or vascular malformation, stroke or brain tumor, congenital malformations, and prior brain surgeries.

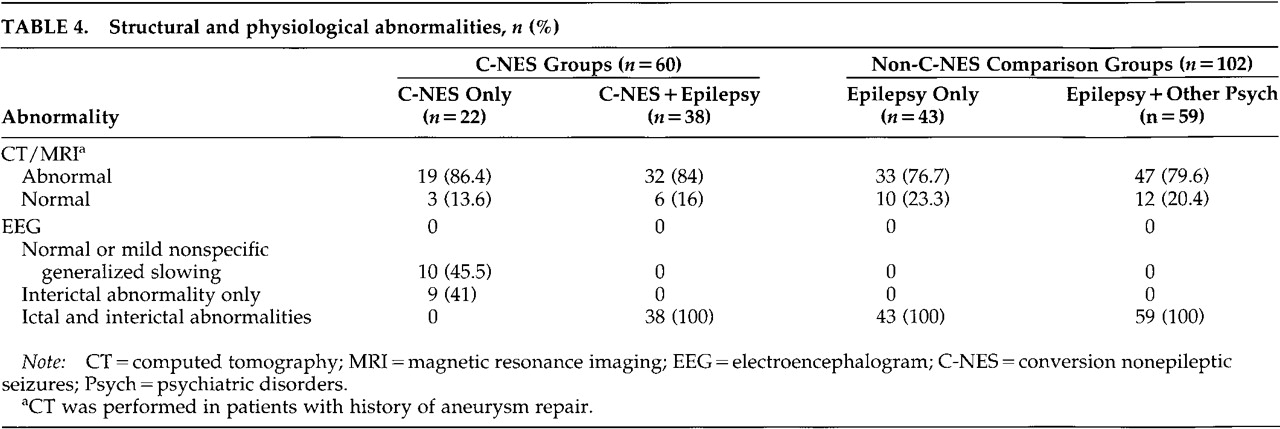

Structural and physiological abnormalities for all groups are summarized in

Table 4. Among the 60 patients in the C-NES groups, 85% had abnormal neuroimaging studies (CT or MRI); on EEG, 78% had definite interictal or ictal epileptiform discharges and another 10% had focal slowing only (i.e., 88% had EEG abnormalities). Two patients had generalized spike and slow-wave discharges and a primary generalized epilepsy syndrome. In the comparison groups, all patients with unilateral structural or physiologic abnormalities had interictal and ictal epileptiform discharges, and 78.4% of them had abnormal neuroimaging studies. Hippocampal atrophy was the most common finding in patients with epilepsy (with and without concurrent C-NES).

In the C-NES groups, brain surgery was performed in 32 patients: resective epilepsy surgery in 15 cases, brain tumor excision in 6, subdural hematoma evacuation in 2, aneurysm repair after subarachnoid hemorrhage in 5, arteriovenous malformation (AVM) repair in 3, and ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt in 1 case. Seventeen of these 32 patients had C-NES develop after brain surgery: surgery for brain tumor in 5, for intracranial hemorrhage in 8, and resective epilepsy surgery in 4 cases. In the comparison groups, brain surgery was performed in 57 patients: resective brain surgery in 45 cases, brain tumor excision in 5, aneurysm repair in 4, AVM repair in 2, and VP shunt in 1 case (

Table 3).

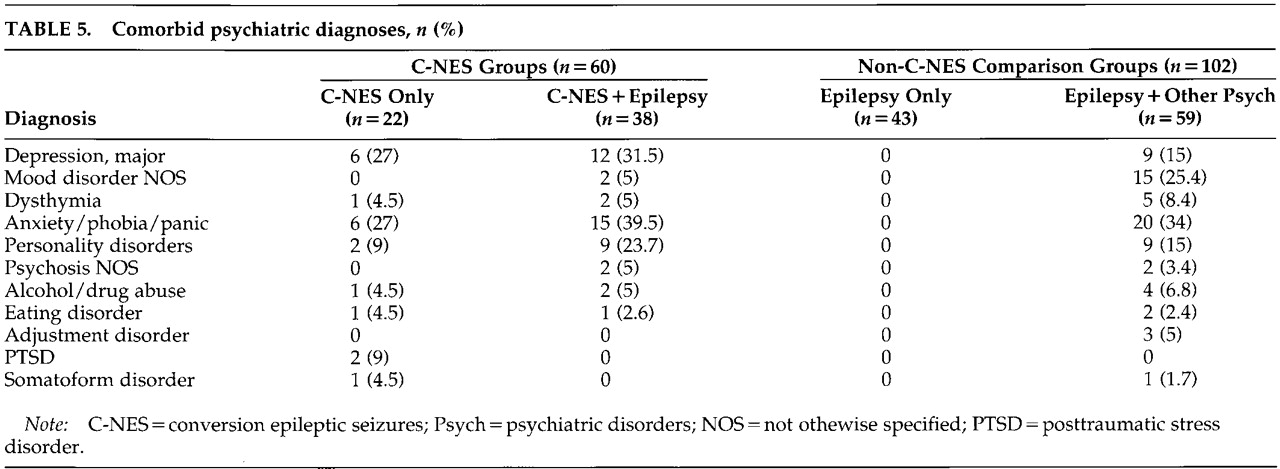

Comorbid psychiatric diagnoses (

Table 5) in the C-NES and comparison groups include major depression, mood disorder not otherwise specified, dysthymia, anxiety, phobia, panic disorder, personality disorders, psychosis not otherwise specified, alcohol and drug abuse, eating disorder, adjustment disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and somatoform disorder. Depression/mood disorder, anxiety, and personality disorders were the most common psychiatric diagnoses in all groups. Nine patients in the C-NES group had other conversion symptoms, including paralysis, ataxia, and nonanatomic sensory loss (data not displayed).

Chi-square analyses showed that the observed right-sided frequencies between the two epilepsy groups were not significantly different from those expected, nor were they different from each other (χ2=0.30, df=1, not significant). Results from the C-NES group showed that these patients had significantly more right-sided structural or physiological abnormalities than expected by chance and were more likely to have lateralizing signs in the right (nondominant) hemisphere than were patients in the combined epilepsy groups (χ2=5.81, df=1, P<0.02).

DISCUSSION

Patients with C-NES have a significantly higher frequency of right hemisphere pathology compared with those epilepsy patients (with or without psychiatric disorders). Our findings suggest that right hemisphere dysfunction may facilitate the development of conversion symptoms, consistent with prior evidence of right hemisphere dominance in emotional regulation

14 and supporting other findings

8–10,15,16 that right hemisphere dysfunction may contribute to the pathogenesis of conversion disorder.

Understanding of the pathogenesis of conversion disorders has advanced little since Janet postulated dissociation and Freud conceived conversion as the relevant mechanism. Extensive discussions of psychodynamic factors and issues related to primary and secondary gain have not provided a scientific framework to refute or prove these hypotheses. Risk factors for conversion disorder, including female sex, physical or sexual abuse, and other emotional traumas, are well defined.

3,17 However, the cognitive and cerebral processes that transform a stressful life event to physical symptoms produced outside of conscious awareness remains a mystery. A recent positron emission tomography (PET) study of script-driven imagery in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder

16 revealed increased blood flow in right hemisphere limbic, paralimbic, and visual areas during recall of emotional images.

The French psychiatrist Briquet observed in 1859

18 that “three left-sided hysterical anesthetics existed for every right-sided one.” Richer and other clinical authorities on hysteria noted a much higher incidence of left-sided than right-sided conversion symptoms.

7,19–21 More recent reviews and clinical studies also documented a left body predominance of conversion symptoms.

8–10,15 This left-sided symptom preference may reflect an attempt to cause the least functional deficit—the “most convenient symptom” (nondominant) theory. However, left-body conversion symptoms are more frequent among both right-handed and left-handed patients, arguing against this mechanism.

15 Patients with hypochondriasis

22 and somatoform rheumatic pain

23 also have a higher frequency of left-sided body symptoms. In multiple personality disorder, a dissociative disorder often preceded by repetitive childhood physical or sexual abuse, approximately one-third of patients report a shift of handedness when they switch to a different personality.

24The reported left-sided preponderance of conversion, hypochondriacal, and somatoform symptoms, and the change in handedness (usually from the right to the left hand) suggests that these symptoms may be more frequently produced by processes mediated by the right hemisphere. Alternatively, a deficit of left hemisphere regulatory functions could “release” right hemisphere emotional centers, thereby evoking conversion symptoms. Our finding that conversion symptoms are more common after right hemisphere lesions supports the mechanism of right hemisphere dysfunction.

Patients with neurological disorders have an increased incidence of conversion disorders,

2,12,13 an association recognized for more than a century.

25,26 Schilder

27 noted in 1939: “Cerebral organic syndromes may change functions of the brain in such a way as to provoke neurotic attitudes. One cannot claim similar mechanisms for traumas which afflict other parts of the body.” Patients with right frontotemporal lesions can have conversion symptoms, such as seizures, induced by suggestive techniques or spontaneously.

28,29 However, conversion disorder can also occur in patients with left hemisphere or bihemispheric dysfunction, as we found in our study and as has been previously reported in small series.

30–32We suggest that conversion disorder involves simultaneously a restriction of conscious awareness and an excessive role of nonconscious processes in behavioral expression. In particular, we suggest that the pathologic conversion symptoms, in contrast to the nonconsciously mediated processes dominating normal cognition,

33 are produced intentionally by nonconscious networks that may also prevent conscious awareness of the intent. Intentional actions, in the form of goal-directed actions, can result from nonconscious processes; in such instances, the “intention” is outside conscious awareness. Conversion disorder patients perceive their symptoms as spontaneous, resulting from some organic process, and are typically shocked when sympathetically presented with the diagnosis. They often reject the “psychological” possibility and seek new physicians.

What nonconscious cognitive process mediates conversion symptoms, and what anatomic structures and networks are activated and inhibited? Our finding that right hemisphere disorders may facilitate the development of conversion symptoms does not necessarily imply that the right hemisphere

produces conversion symptoms. But can dysfunction in the right hemisphere contribute to the restriction of conscious awareness of the production of these symptoms? It is known that right hemisphere dysfunction can impair conscious awareness of body parts, neurological deficits (e.g., anosognosia), sensory input, and emotional and social cues.

34We hypothesize that the right hemisphere usually represses or positively redirects traumatic emotions and memories. The right hemisphere may process emotionally valent experiences, facilitating the acceptance of those events and resolving unpleasant feelings. Right hemisphere dysfunction in conversion disorder patients is consistent with the growing evidence that the right hemisphere dominates the processing, comprehension, and expression of emotions.

14,35,36 In conversion disorder, there may be a restriction in the conscious fields of attention, memory, and emotions, leading to a subconsciously generated behavior through which prior emotional memories resurface and are expressed as somatic symptoms.

Right hemisphere lesions may thus impair capacity to “psychologically handle” painful emotions and, simultaneously, impair awareness of self-features (as in anosognosia) and self-generated behaviors such as conversion symptoms that would otherwise be accessible to consciousness. In a functional imaging study, a woman with a conversion paralysis of her left leg was asked to move her left leg. The attempt to move the paralyzed leg failed to activate right primary motor cortex. Instead, the right orbitofrontal and right anterior cingulate cortex were significantly activated. In this case, these two areas may have inhibited prefrontal (consciously willed) effects on the right primary motor cortex when the patient tried to move her left leg.

37Our study suggests that right hemisphere injury may contribute to the development of conversion disorder. However, emotional conflict on its own may provoke conversion or other dissociative disorders. The finding that conversion symptoms typically occur in younger women exposed to adverse environmental influences and having disturbed personality development strongly argues against a primary organic pathogenesis in most conversion patients. However, psychological factors may in themselves produce primary disruption of right hemisphere functions controlling emotions, willed actions, and self-monitoring.