Behavioral alterations in Huntington's disease (HD) are often the most distressing aspect of the condition for both patients and caregivers and are therefore often central to the practical clinical management of patients. Nevertheless, indices of disease severity are usually based on motor and cognitive measures. Experimental therapeutic interventions with striatal cell implants and neuroprotective agents aim to retard disease progression and restore basal ganglia function. If such treatments are to be successful, they should address behavioral as well as motor and cognitive symptoms. It is therefore important to understand how behavioral alterations are related to other features of HD.

Previous research has produced equivocal findings regarding this issue; some studies have shown a relationship between behavioral alterations and measures of disease severity;

1–3 however, most have not.

4–8 This has led some researchers to conclude that unlike the cognitive and motor aspects of the condition, behavioral changes are “heterogeneous, episodic, and without clear additive temporal progression.”

8 However, previous studies have focused primarily on affective changes such as depression and irritability, which are not representative of the full range of behavioral changes in HD.

In addition to depression and irritability, amotivational states such as apathy and abulia are also common in HD,

9 and although they are clinically striking, little is known about how they relate to other aspects of the condition. It is now well documented that there are characteristic cognitive changes in HD, particularly in the realm of executive functions. Patients exhibit difficulty with tasks that require the ability to plan, organize, sequence, shift cognitive set, and hold information “on line” in order to guide actions. It is possible that amotivational states are related to these cognitive changes. For example, an inability to plan and think ahead might be associated with a loss of initiative and drive. The hypothesis arising from this supposition is that certain aspects of behavioral change are related to cognition and so ought to be associated with cognitive impairment, whereas others are mood-based and unrelated to cognition.

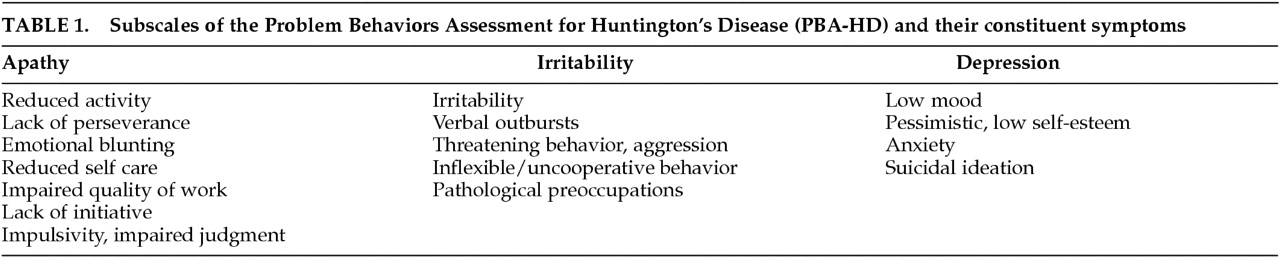

Our own research using the Problem Behaviors Assessment for Huntington's Disease (PBA-HD) supports the separation of behavioral changes into different components. Craufurd et al.

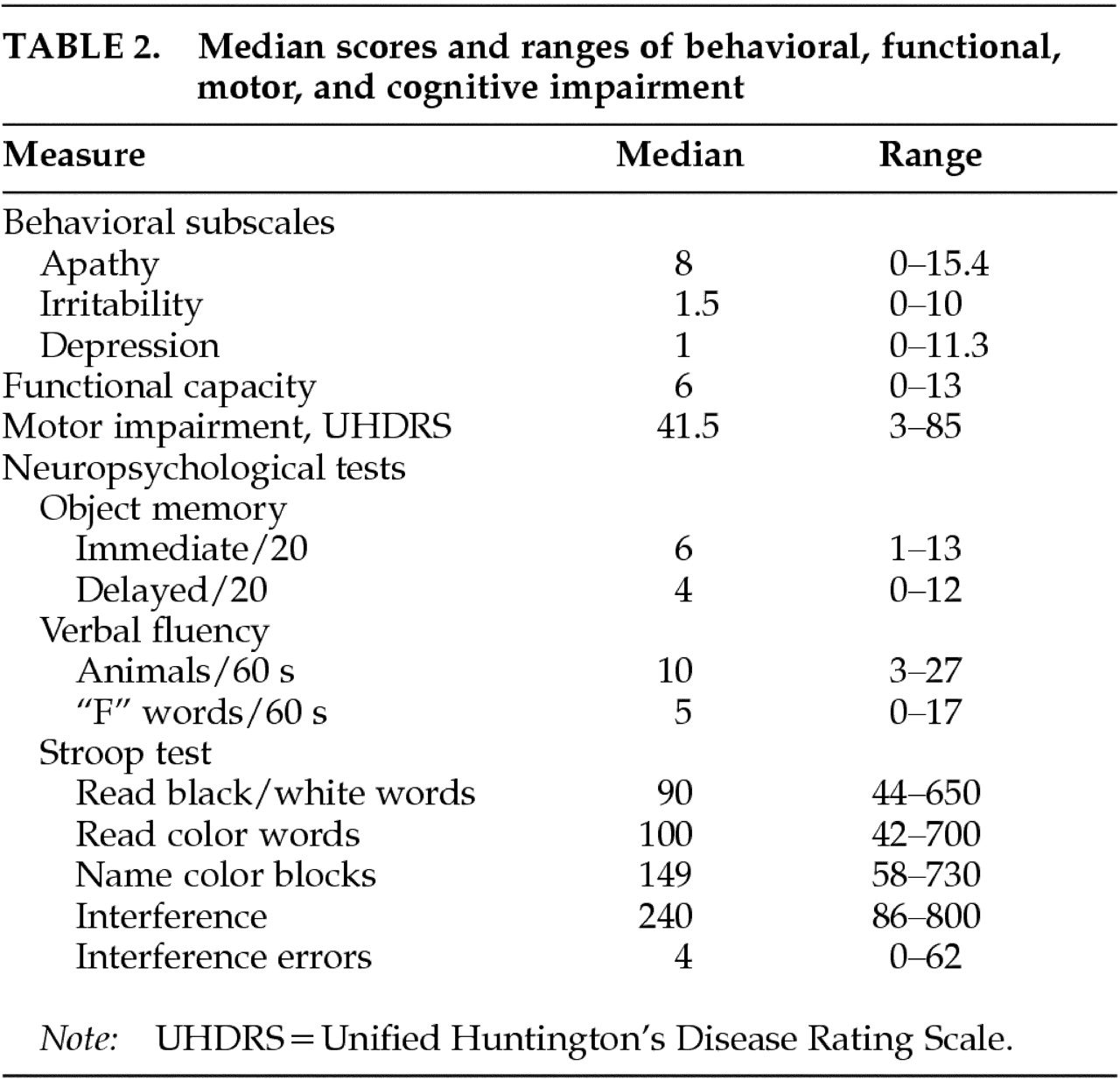

10 assessed 134 HD patients with the PBA-HD and, using factor analysis, distinguished three subscales of highly intercorrelated items (

Table 1). The first subscale consisted of reduced activity and initiative, poor perseverance and quality of work, altered judgment, personal neglect, and emotional blunting, and was termed the Apathy subscale. The second subscale comprised symptoms of inflexibility, pathological preoccupations, poor temper control, and verbal and physical aggression, and was termed the Irritability subscale. The third subscale included low mood, depressive cognition, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, and was named the Depression subscale. We have demonstrated good interrater and test-retest reliability using this scale.

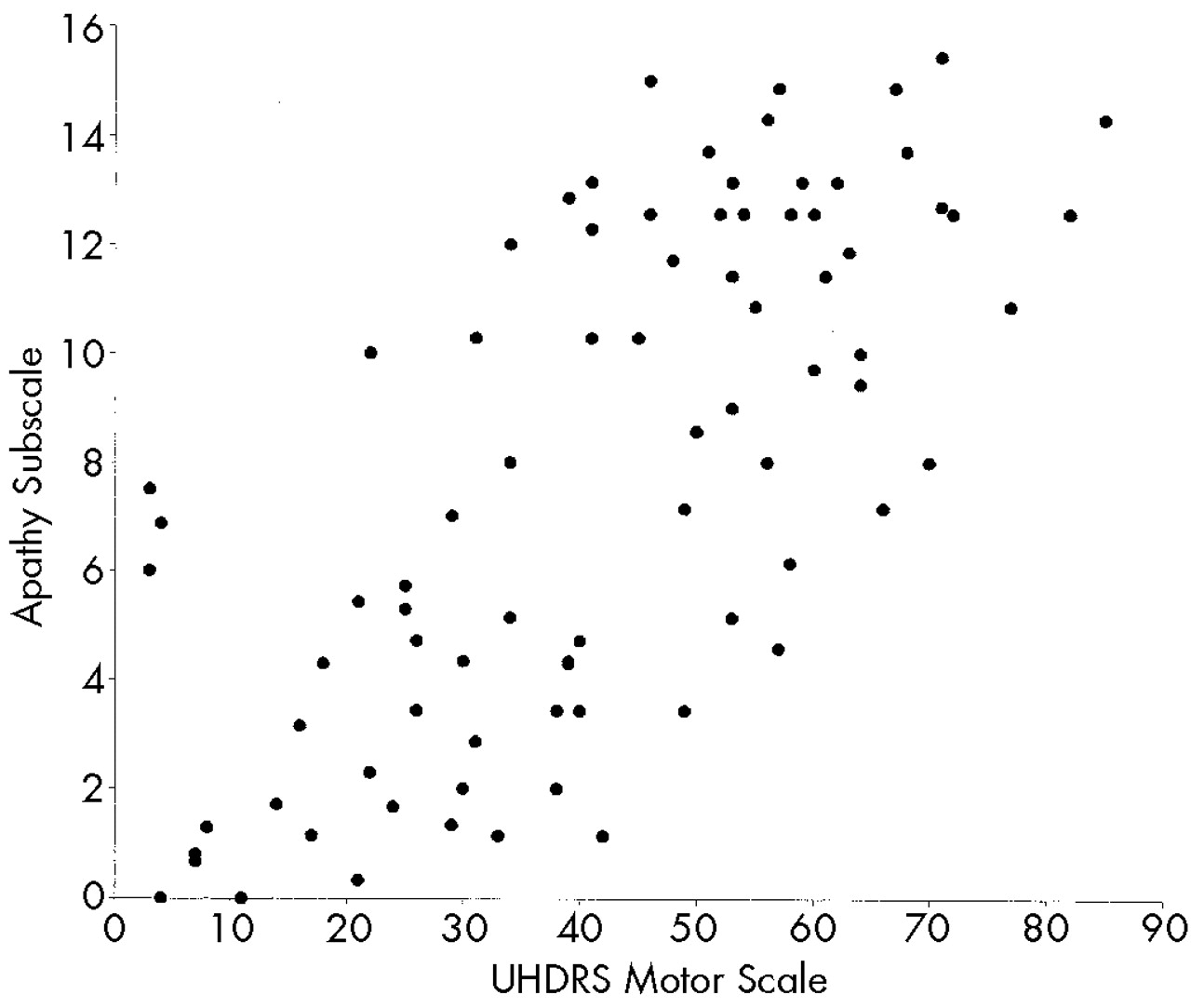

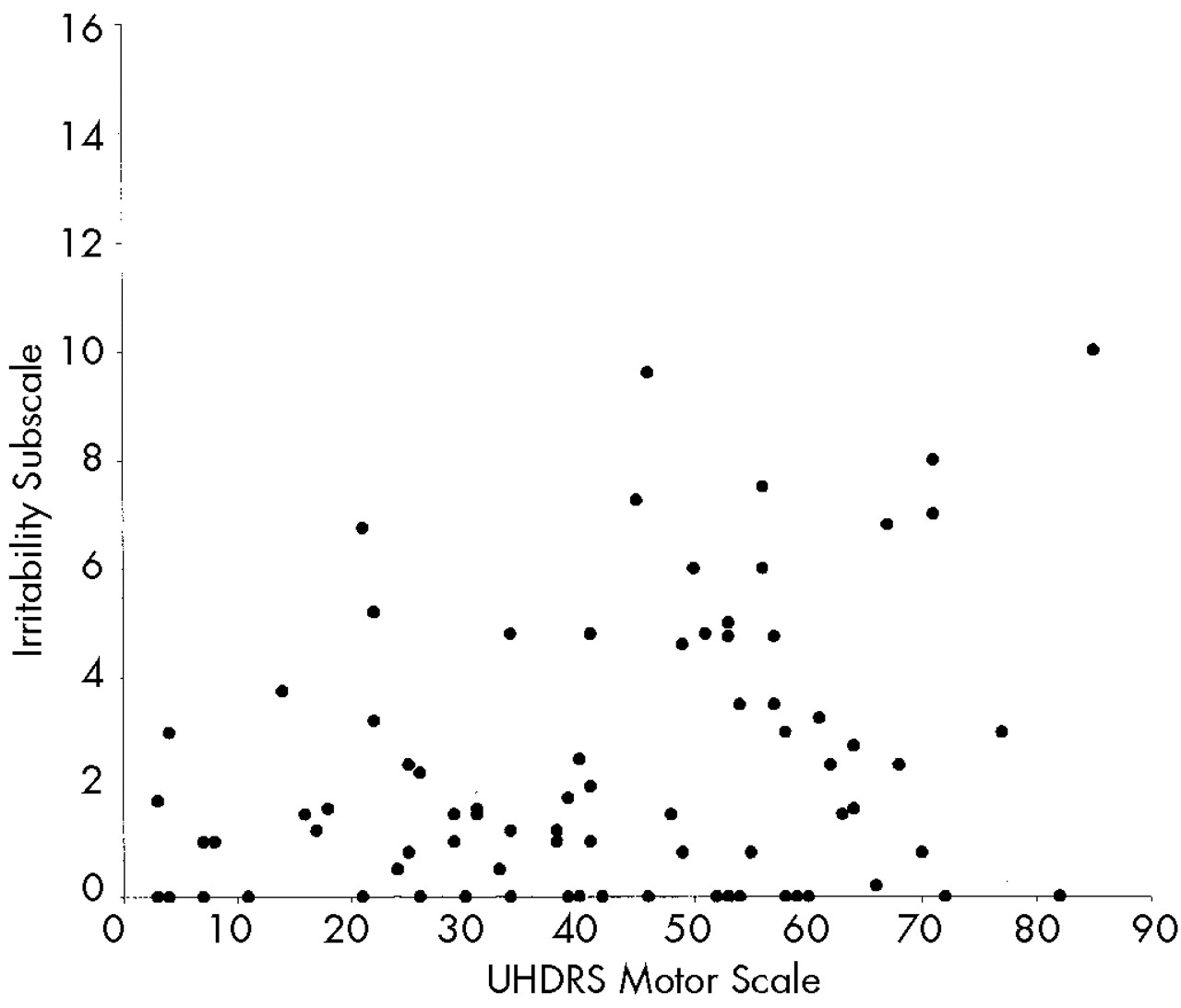

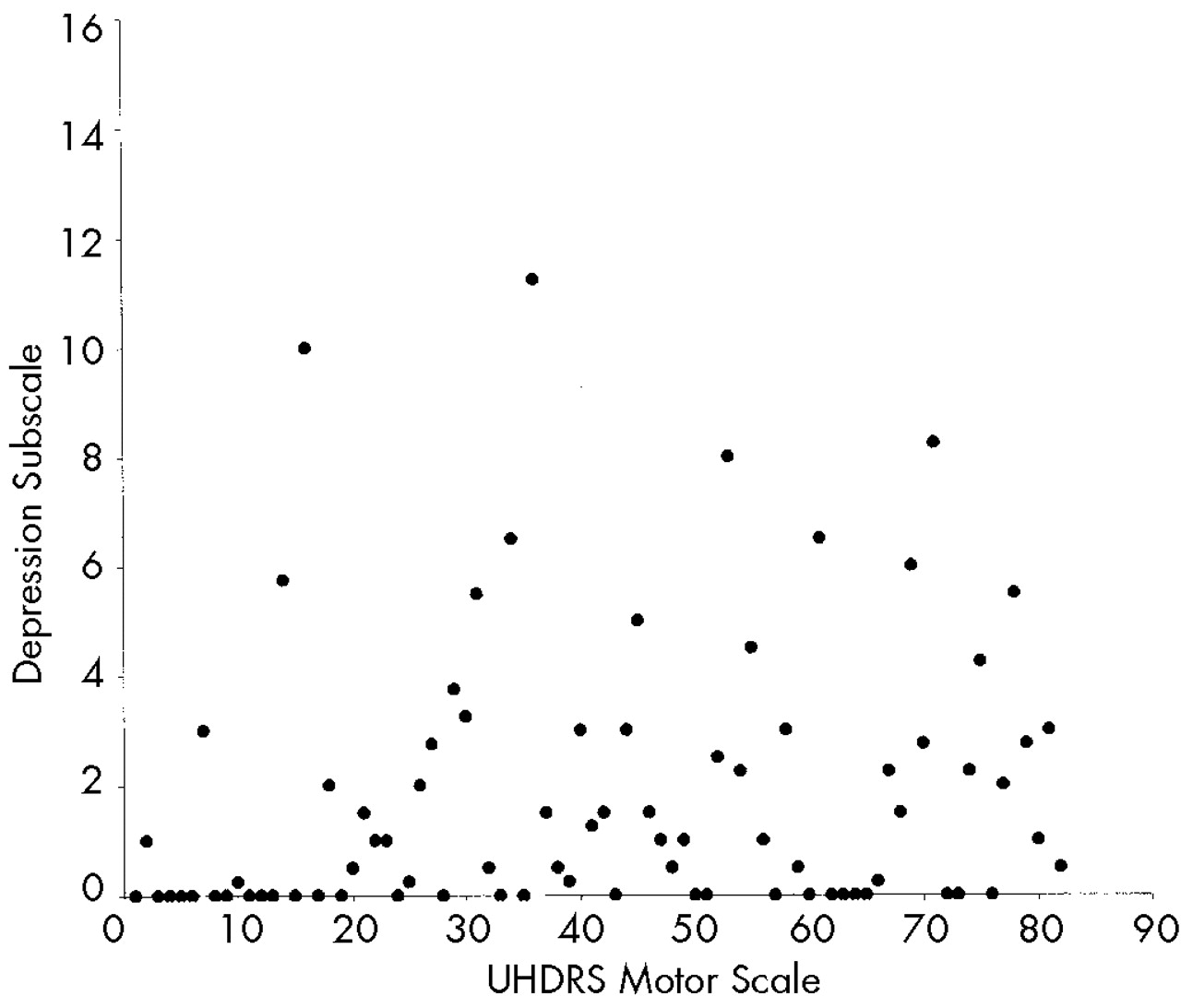

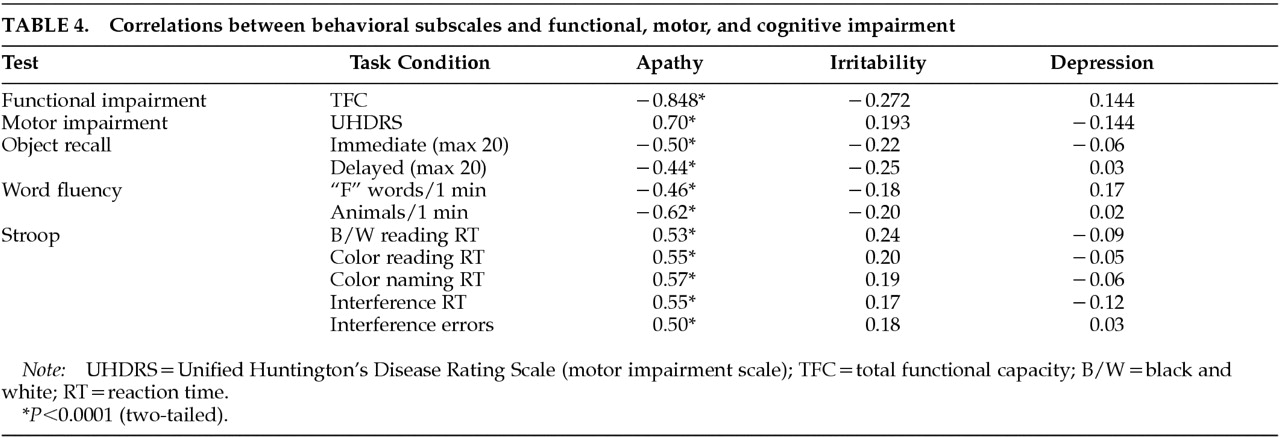

The aim of the present study was to examine how different aspects of behavioral change in HD relate to other indices of disease severity. We hypothesized that scores on the Apathy subscale of the PBA-HD would correlate with cognitive and motor measures of disease progression, whereas scores for the Irritability and Depression subscale would not.

DISCUSSION

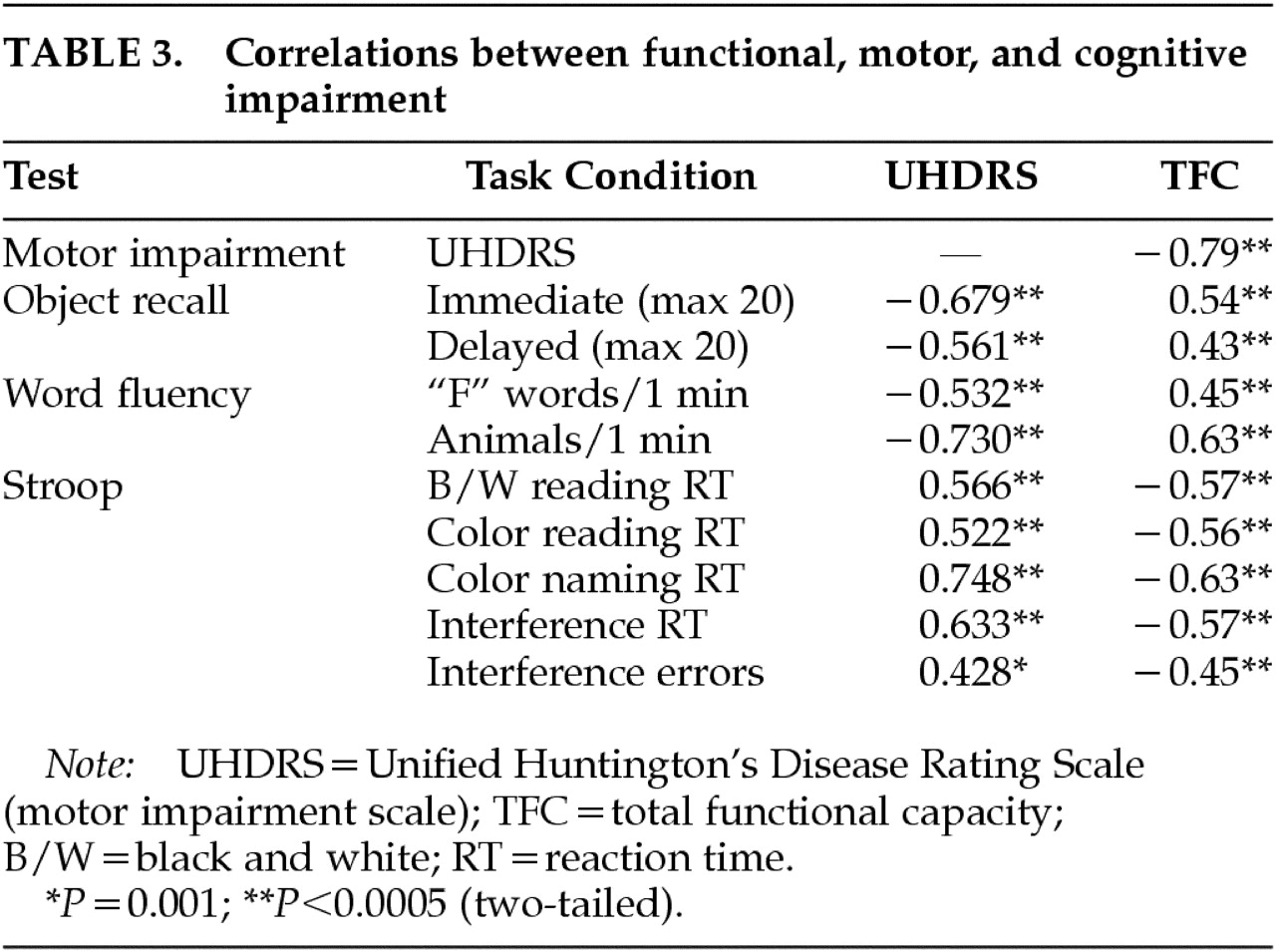

We hypothesized that behavioral alterations in HD could be subdivided into those that are related to cognitive change and those that are independent of altered cognition. Consistent with our prediction, we observed strong relationships between measures of cognition and motor function and scores on the Apathy subscale of the PBA-HD. In contrast, the Irritability and Depression subscales, which reflect mood-based changes, were uncorrelated with either cognitive or motor impairment.

These findings help to resolve apparent disparities in the literature. Previous studies that found no relationship between behavioral change and other markers of disease progression

4–8 focused on affective changes such as depression, anxiety, and irritability. This is consistent with our finding that the Depression and Irritability subscales did not correlate with motor and cognitive measures of disease progression. A small number of studies have shown a relationship between behavioral symptoms and other indices of disease progression. A study by Levy et al.

3 is of particular relevance to our findings. Although principally concerned with the association between apathy and depression, the authors observed that while depression did not correlate with cognitive impairment (as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination), apathy did. This is in keeping with our finding that the Apathy subscale of the PBA-HD correlated with cognitive and motor impairment.

We observed highly significant correlations between motor and cognitive impairment, both of which have been shown to correlate with PET measures of striatal dopamine binding,

13,14 adding support to the notion of a common anatomical substrate. Furthermore, the Apathy subscale of the PBA-HD and its constituent items were highly correlated with motor and cognitive function as well as functional capacity. This finding supports the view that components of behavior subsumed within the Apathy scale, which includes both quantitative reductions in activity and loss of emotional response, are fundamental to the evolution and progression of HD. Functional capacity is a global measure of independence in the activities of daily living, and as such it is likely to be related to some of the items on the Apathy scale as well as to overall motor disability and cognitive impairment. However, functional capacity is a well-recognized measure of disease progression, and the finding that the Apathy subscale was so highly correlated with this and other indices of disease severity suggests that the Apathy subscale is indeed a valid measure of severity in HD.

Neither the Depression nor the Irritability subscale correlated with cognitive or motor impairment. In view of the reduced range of scores and skewed distributions of these scales, it is necessary to exercise caution in interpreting this finding. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with previous studies which have also shown that affective changes do not correlate with indices of disease severity. The absence of a correlation should not be interpreted as evidence that depression and irritability are unrelated to HD; however, it does suggest that these symptoms would be less suitable for monitoring disease progression in therapeutic trials. Nevertheless, depression and irritability are common features of HD, and therefore it would be important to monitor their occurrence, particularly in future trials designed to delay disease onset.

The nature of the relationship between the Apathy subscale and cognitive impairment is worth considering. Apathy is a common feature in neuropsychiatric disorders, and has been shown to correlate with cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease

15 and frontotemporal dementia.

3 One possible explanation of the link between scores on the Apathy subscale and cognitive impairment in HD is that both arise from striatal pathology, which gives rise to a disruption in striatofrontal circuits. Specific impairments are associated with damage to these different circuits: the dorsolateral circuit is associated with impaired executive function, the anterior cingulate circuit with apathy, and the orbitofrontal circuit with disinhibition.

16 Damage to these striatofrontal circuits in HD could therefore account for apathy as well as motor and cognitive impairment.

It is also possible that some of the behavioral alterations on the Apathy subscale are fundamentally related to impaired executive function—that is, that apathy and executive dysfunction both reflect a common underlying deficit. Executive functions include the planning, programming, regulation, and verification of goal-directed behavior. Reduced activity and initiative may be explained in terms of an inability to generate and execute plans. Similarly, impaired judgment, often manifested as impulsivity, may result from a failure to think plans through properly and consider their consequences. Poor perseverance could result from an inability to hold information “on line” using working memory.

Given that depression and irritability are such common features of HD, the finding that they do not appear to relate directly to progression of the disease warrants further discussion. One possible explanation is that these symptoms may not develop linearly, unlike those included on the Apathy subscale. Indeed, it has been proposed that certain types of behavioral change characterize different stages of the illness: irritability and aggression in the early stages; depression, mania and psychosis in the middle stages; and apathy and abulia in the late stages.

9 It is quite possible that these affective disturbances subside as patients become more apathetic and emotionally blunted. The apparent nonlinear progression of affective symptoms may also in part be due to the responsiveness of these symptoms to psychotropic medication. These factors are unlikely to afford a complete explanation, however, as affective symptoms, although common in HD, are not the ubiquitous feature of the illness that apathy appears to be. Further research is required to begin to understand why certain individuals are more susceptible to depression and irritability. It is possible that other variables, such as genetic factors and premorbid personality characteristics, contribute to the presence and severity of affective disturbances. Longitudinal studies of behavioral alterations in HD should help to resolve these issues.

The patient group encompassed a wide range of disease severity and included some individuals with atypically early or late onset of symptoms. It is generally accepted that behavioral alterations are more severe in patients with an earlier onset and less severe in patients with a later onset. However, in a previous study we found that youthful and elderly patients did not differ significantly from the group mean in terms of overall number of behavioral symptoms or in scores on the three PBA-HD subscales, which suggests that onset age is not a factor that would affect the results of the current study.

The present study resolves some of the discrepancies in the published literature regarding the relationship of behavioral changes in HD to other indices of disease severity. The results indicate that certain behavioral changes are fundamental to the evolution and progression of HD, whereas affective changes such as depression and irritability are more variable and are not directly related to cognitive and motor measures of disease progression. This has implications for the choice of behavioral measures used to assess therapeutic efficacy in treatment trials. In explaining these findings, we highlight the link between behavior and cognition and postulate that certain behavioral alterations may be related to impaired executive functions in HD.