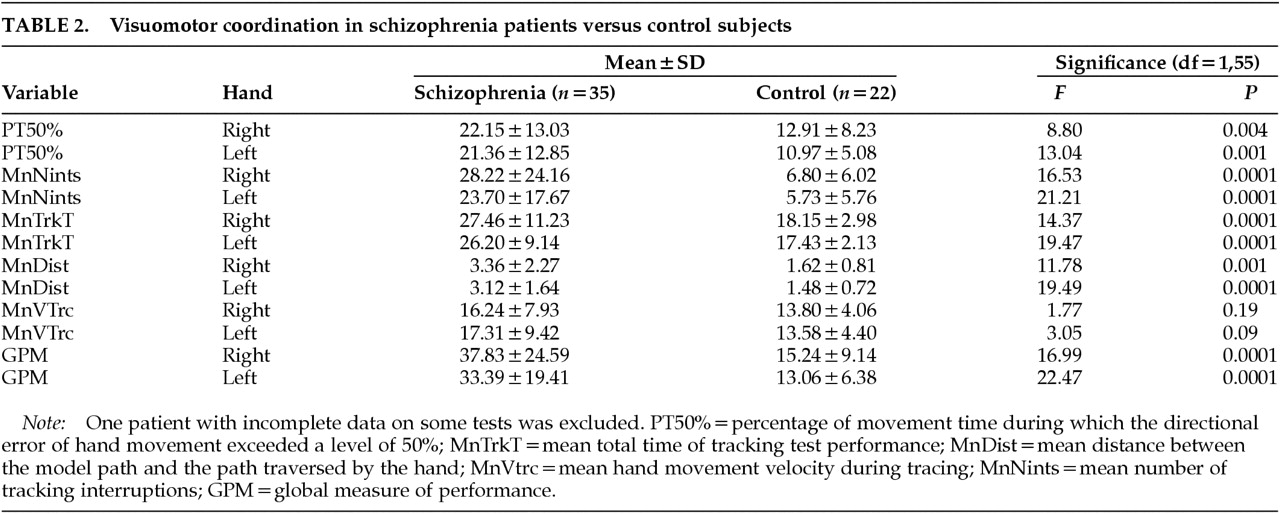

Table 2 shows the performance of patients and control subjects on the five parameters tested. Schizophrenic patients performed significantly worse than control subjects on all measures except velocity of tracing. VMT performance was not influenced by age or sex. In the patient group there was no significant correlation between VMT measures and extrapyramidal side effects or involuntary movements. (GPM vs. SA score:

r=–0.17 right hand,

r=–0.11 left hand, not significant; GPM vs. AIMS score:

r=0.12 for both hands, not significant). There was no significant correlation between VMT measures and scale scores, except for BPRS, which showed a correlation with PT50% right hand (

r=0.37,

P=0.03).

There was no consistent significant correlation between VMT performance and illness parameters. These included age at first admission (except for correlation with PT50% left hand: r=0.37, P=0.03), illness duration (except for correlation with MnDist left hand: r=0.44, P=0.008), number of admissions, and accumulated time in hospital (except for correlation with PT50% right hand: r=0.34, P=<0.05, and MnDist right hand: r=0.49, P=0.003).

Right hand performance was worse than left in both groups.

There was no difference in VMT performance in patients taking different atypical antipsychotics or between patients with or without anticholinergic treatment.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of the present study was that schizophrenic patients showed impaired visuomotor function compared with normal subjects. The deficits were mainly in the ability to control movement direction when tracing simple patterns and in keeping pace with a moving target in tracking tests. Velocity of movement, however, was not impaired.

The patients' impairment was not due to extrapyramidal side effects: the patients were on atypical antipsychotics, they had no or few extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) as measured on the SA scale, and there was no relationship between SA scores and VMT performance. Likewise, anticholinergic co-administration did not influence results. Nonetheless, the possibility that subtle effects of medication not detected by scales contributed to the findings cannot be entirely excluded.

There was no consistent relationship between VMT performance and illness characteristics such as age at first admission, length of illness, or cumulative hospitalization time, although some correlations were noted. Nor was there an overall significant relationship with levels of positive or negative symptoms.

The lack of relationship to these illness variables suggests that visuomotor deficit may be a traitlike characteristic in schizophrenia, linked to basic CNS pathology similar to eye movement abnormalities.

5 However, the possibility that factors related to illness chronicity contributed to the findings cannot be excluded. In this regard, nonspecific factors such as poor motivation or generalized motor slowing did not appear to be significant confounds, since the patients cooperated willingly and their movement velocity on tracing tests did not differ from that of control subjects.

Of the many changes that underlie and accompany schizophrenia, the reduced connectivity between remote cortical regions

10,11 is likely to be a major factor in reducing visuomotor capabilities. As already noted, normal visuomotor function depends on availability of visuospatial information, processed in posterior parietal and superior temporal areas, to premotor regions.

7–9 Reduced corticocortical connectivity is likely to attenuate this information flow to a level that impairs performance. Similarly, reduced interhemispheric cross-talk may result in greater manual asymmetry during execution of tasks that are controlled preferentially by one hemisphere or the other. Visuomotor coordination is thought to be related to right hemisphere processes

19 and is therefore likely to be more impaired in the right hand when interhemispheric communication is disrupted. However, we did not perform a detailed assessment of performance by hand.

Impaired control of eye movements, well documented in schizophrenia,

20–22 may also contribute to visuomotor deficits. Normal control of eye movements is necessary for successful visually guided hand movements. In addition, the same neural pathology causing abnormal saccades and visual tracking may be involved in reduced coordination,

23 so that impaired eye movements may interfere with visuomanual coordination directly and through a shared neural abnormality.

There is evidence that eye movement dysfunction, in particular the characteristic deficit in velocity discrimination,

5,24,25 may be localized to motion-sensitive areas of the parietal lobe, middle temporal (MT), and medial superior temporal (MST) areas and their associated networks,

5,24,25 including in the prefrontal cortex

26 and the occipital lobe.

27 It is possible that defects in these areas may also underlie VMT abnormalities.

Impaired attention, common in schizophrenia,

28,29 may also reduce VMT. Lowered attentional resources are likely to increase the number of tracking interruptions and may be manifested in greater distance from the desired path during tracing. Our results show that patients with schizophrenia perform much worse than normal subjects on both variables.

In summary, the present study shows a marked reduction in the visuomotor capabilities of individuals with schizophrenia, despite the absence of extrapyramidal side effects and despite treatment with atypical neuroleptics. The possibility that this deficit may be a core attribute of schizophrenia that can be related to other well-documented functional changes in this disease merits further study.